[1]

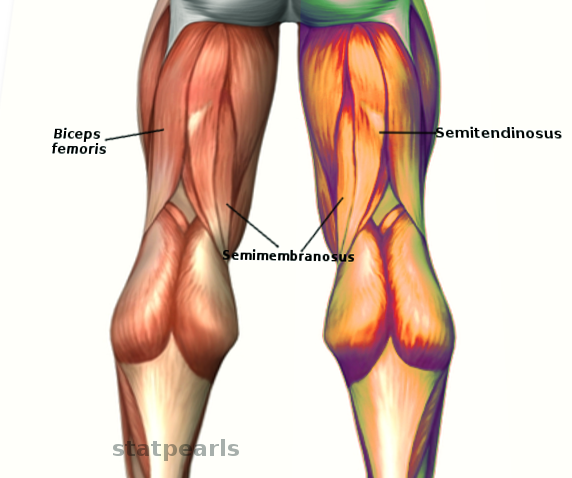

Mathew K, Pillarisetty LS. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Thigh Semitendinosus Muscle. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30969684]

[2]

Hyland S, Sinkler MA, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Popliteal Region. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30422486]

[4]

Koulouris G, Connell D. Hamstring muscle complex: an imaging review. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2005 May-Jun:25(3):571-86

[PubMed PMID: 15888610]

[5]

Azzopardi C, Almeer G, Kho J, Beale D, James SL, Botchu R. Hamstring origin-anatomy, angle of origin and its possible clinical implications. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2021 Feb:13():50-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.08.021. Epub 2020 Sep 17

[PubMed PMID: 33717874]

[6]

Chakravarthi K. Unusual unilateral multiple muscular variations of back of thigh. Annals of medical and health sciences research. 2013 Nov:3(Suppl 1):S1-2. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.121206. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24349835]

[7]

Bodendorfer BM, Curley AJ, Kotler JA, Ryan JM, Jejurikar NS, Kumar A, Postma WF. Outcomes After Operative and Nonoperative Treatment of Proximal Hamstring Avulsions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine. 2018 Sep:46(11):2798-2808. doi: 10.1177/0363546517732526. Epub 2017 Oct 10

[PubMed PMID: 29016194]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[8]

Frank RM, Hamamoto JT, Bernardoni E, Cvetanovich G, Bach BR Jr, Verma NN, Bush-Joseph CA. ACL Reconstruction Basics: Quadruple (4-Strand) Hamstring Autograft Harvest. Arthroscopy techniques. 2017 Aug:6(4):e1309-e1313. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.05.024. Epub 2017 Aug 14

[PubMed PMID: 29354434]

[9]

Chu SK, Rho ME. Hamstring Injuries in the Athlete: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Return to Play. Current sports medicine reports. 2016 May-Jun:15(3):184-90. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000264. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27172083]

[10]

Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during slow-speed stretching: clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and recovery characteristics. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007 Oct:35(10):1716-24

[PubMed PMID: 17567821]

[11]

Askling C, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Type of acute hamstring strain affects flexibility, strength, and time to return to pre-injury level. British journal of sports medicine. 2006 Jan:40(1):40-4

[PubMed PMID: 16371489]

[12]

Ali K, Leland JM. Hamstring strains and tears in the athlete. Clinics in sports medicine. 2012 Apr:31(2):263-72. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2011.11.001. Epub 2011 Dec 21

[PubMed PMID: 22341016]

[13]

Koulouris G, Connell D. Imaging of hamstring injuries: therapeutic implications. European radiology. 2006 Jul:16(7):1478-87

[PubMed PMID: 16514470]

[14]

Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2010 Feb:40(2):67-81. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3047. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20118524]

[15]

Sherry MA, Johnston TS, Heiderscheit BC. Rehabilitation of acute hamstring strain injuries. Clinics in sports medicine. 2015 Apr:34(2):263-84. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.12.009. Epub 2015 Jan 28

[PubMed PMID: 25818713]

[16]

Levine WN, Bergfeld JA, Tessendorf W, Moorman CT 3rd. Intramuscular corticosteroid injection for hamstring injuries. A 13-year experience in the National Football League. The American journal of sports medicine. 2000 May-Jun:28(3):297-300

[PubMed PMID: 10843118]

[17]

Hamid MS, Yusof A, Mohamed Ali MR. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for acute muscle injury: a systematic review. PloS one. 2014:9(2):e90538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090538. Epub 2014 Feb 28

[PubMed PMID: 24587389]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence