Continuing Education Activity

Salivary gland tumors are characterized by diverse histological appearances and variable biological behavior. The distinction between tumor types can be difficult, particularly based on material from fine-needle aspiration (FNA). This activity outlines the evaluation and management of salivary gland tumors and reviews the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Outline the types of salivary gland tumors.

- Describe how to properly evaluate a patient for salivary gland tumors.

- Review the treatment and management options available for salivary gland tumors.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies to improve care for patients with salivary gland tumors.

Introduction

Salivary gland neoplasms may be benign or malignant, and malignant tumors can be primary or metastatic. Due to the epithelial and the non-epithelial histology of the affected organ, many histological types of parotid tumors are possible, although some are rare.[1] Salivary gland tumors are characterized by diverse histological appearances and variable biological behavior. The distinction between tumor types can be difficult, particularly based on material from fine-needle aspiration (FNA). There are several other aspects of salivary gland tumors that make them interesting. The commonest benign tumor (pleomorphic adenoma) has a malignant transformation potential, and, although considered benign, there is a propensity for recurrence after treatment.[2] It is not surprising that with such a wealth of pathology, clinical features, investigation issues, and contentious treatment options that salivary gland neoplasms are regularly used in clinical examinations.

Malignant salivary gland tumors usually present after the 6th decade of life, whereas benign lesions present in the 4-5th decade of life. Benign lesions tend to be more common in women, but malignant lesions tend to occur with equal frequency in both genders. The majority of salivary gland tumors occur in the parotid, about 10% occur in the submandibular gland, and less than 4% occur in the minor salivary glands. Most parotid gland tumors are benign, of which the most important is the pleomorphic adenoma. On the other hand, lesions occurring in the submandibular gland and the minor salivary glands are more likely to be malignant.

Mortality from salivary gland tumors depends on the stage. Five-year survival averages about 70%.

Etiology

There are two main theories of how salivary gland tumors arise, but the consensus is with the multicellular theory, that each tumor type forms from a specific differentiated cell of origin within the salivary gland unit. Excretory stem cells give rise to mucoepidermoid and squamous cell carcinomas, while intercalated stem cells can lead to pleomorphic adenomas, adenoid cystic carcinomas, oncocytomas, adenocarcinomas, and acinic cell carcinomas.

Radiation exposure has been linked to parotid gland carcinomas 15 years after the event. Cigarette smoking and alcohol is associated with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, skin malignancies in the head and neck have been known to metastases to the parotid glands. Some cases of a link between occupational exposure to silica dust and nitrosamines have been reported.[3]

It is important to note that both alcohol and smoking are not linked to salivary gland tumors, except for Warthin tumors.

Epidemiology

Salivary glands are a common source of benign pathology; malignant tumors are rare. Approximately 300 cases per year of primary salivary gland malignancy are registered in the United Kingdom, of which fewer than ten occur in children.[4] Patients with malignant lesions typically present in their sixth decade. The worldwide incidence is estimated at 0.5 to 3.0 per 100,000 per year, accounting for about 5% of all head and neck malignancies.[5][6] The overall 5-year survival of malignant salivary disease depends on the stage of the disease but has been reported around 70%.

Pathophysiology

The WHO histological classification of salivary gland tumors now includes over 40 variants as well as tumor-like lesions (e.g., salivary gland cysts). A simplified classification is presented below:

- Benign: Pleomorphic adenoma, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma), myoepithelioma, basal cell adenoma, oncocytoma, cystadenoma.

- Malignant: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), undifferentiated carcinoma, carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma, polymorphous low grade carcinoma

- Hematolymphoid: Hodgkin lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma.

- Non-epithelial: Haemangioma, lymphangioma, neurofibromas

Carcinomas can further be classified as high grade, low grade, or mixed, the latter indicating a variable behavior depending on the histological picture. It is important to recognize that the clinical behavior of a tumor rather than the histology can provide a better treatment guide, and it is recommended that clinical factors, in addition to histology and grade, are considered when treatment planning. Salivary gland tumors are uncommon in children, but a greater proportion of them (30%) are malignant and are usually low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

A good rule of thumb to remember is the rule of 80s; that 80% of all salivary tumors are in the parotid, 80% of parotid tumors are benign, and 80% of the benign tumors that arise in the parotid are pleomorphic adenomas. Warthin’s tumor is the second most common benign lesion. The most common malignant tumor is mucoepidermoid carcinoma, followed by acinic cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. It is also important to remember that the parotid gland is a common site for metastases from squamous cell carcinomas arising in the skin of the head and neck.

Several oncogenes have been implicated in salivary gland tumors. Mutations of P53, MDM2, Bcl-2, and ras have been found in both benign and malignant lesions.

Histopathology

Malignant tumors[4]

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

This is the most prevalent malignant major salivary gland tumor and arises in any salivary tissue but predominantly the parotid gland. It is the commonest salivary neoplasm in children. Low-grade or well-differentiated tumors usually behave benignly, intermediate ones are more aggressive and high-grade, or undifferentiated tumors metastasize early to regional lymph nodes and carry a poor prognosis. However, the behavior is not always accurately predicted by the histological appearance. Five-year survival varies between 86% for low-grade and 22% for high-grade tumors.

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

This is overall (for all glands) the most frequent malignant salivary gland tumor and may arise from any salivary tissue, but is more common in the minor (rather than in major) salivary glands. The gender incidence is equal, and they are seen most often in patients in their sixth decade. The tumor usually presents as a slow-growing mass and tends to spread along nerve sheaths. The patients often complain of facial pain and may present with facial paresis. The incidence of lymph node metastases is low. Local recurrences are common, and distant metastases occur in 30% to 40% patients, usually in the lungs, many years later. Stage I and II cancers have good cure rates, although the prognostic survival curve never flattens even after 20 years. Patients with stage III and IV diseases have a poorer prognosis with low survival rates (as low as 15% to 50%) at 10 years. Patients with lung metastases may live up to 5 years before succumbing to the disease.

Acinic Cell Carcinoma

This is the third most common cancer of the parotid gland. These grow slowly and usually do not spread to local nodes. However, they do recur or present with distant metastases many years after apparent disease-free survival. This is reflected in excellent survival rates of 90% at 5 years, which drops to 55% at 20 years.

Polymorphous Adenocarcinoma

Polymorphous adenocarcinoma is increasingly recognized, particularly as a tumor of the minor salivary glands on the soft palate. It is rare in the parotid. It is easily confused histologically with pleomorphic adenoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. It generally behaves in an indolent, low-grade fashion, but can be unpredictable with perineural invasion and lymph node metastases.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Most cases of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are metastases to the parotid from skin cancers. Associated neck nodes are common so that these cases should also have an elective selective neck dissection, even in an N0 neck. Squamous cell carcinoma tends towards early extracapsular extension. In the parotid, this may threaten local structures and so prompt surgical intervention is required. A few weeks’ delays can make a significant difference to the complexity of the planned surgery, with tumors readily invading the skin and surrounding structures.

Lymphomas

Lymphomas may develop in intra-parotid lymph nodes. The risk of lymphoma is increased in patients with Sjogren syndrome. They can be confused with Warthin tumor on cytology, and larger tissue samples are usually requested, and immunohistochemistry is required.

Benign lesions

Pleomorphic adenoma is commonly found in the parotid gland and affects both genders equally. The tumors are slow-growing and cause no symptoms. The lesions have a smooth texture and are surrounded by a capsule. Lesions that have pseudopodia are most likely to recur after surgery. Most superficial lesions can be removed with simple enucleation. Damage to the facial nerve can occur and is associated with high morbidity.

Warthin tumor is the 2nd most common benign lesion. The tumor is more common in men than women and is known to be bilateral in 10%-15% of cases. It has been linked to smoking and presents after the 4th decade of life.

Oncocytomas are rare tumors that occur in older patients. These lesions are firm and are identified using electron microscopy.

Monomorphic adenomas may feel like pleomorphic adenomas but lack the pleomorphic features. These slow-growing lesions are benign and likely to occur in the minor salivary glands.

History and Physical

The usual presentation is a slow-growing painless mass. Rapid growth, pain, tethering of the skin, ulceration of the skin, cervical lymphadenopathy, and facial nerve paralysis are all suggestive of malignancy. Tumors low in the tail of the parotid gland can easily be confused with an upper cervical lymph node. Bilateral parotid tumors are most common in Warthin tumors and HIV related lymphoepithelial cysts. Taking a detailed history is important in treating patients with parotid lumps, as infectious, autoimmune, and inflammatory processes may masquerade as neoplasms.

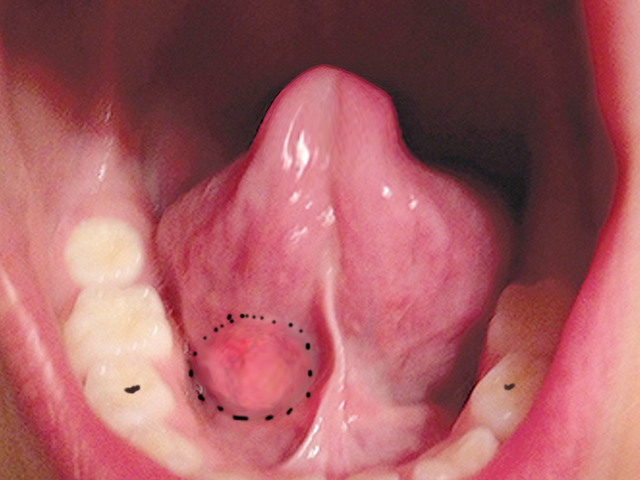

All patients with a mass in a salivary gland should have an inspection and palpation of the mass itself. The oral examination should be with an inspection of the relevant salivary gland duct. The submandibular duct (Wharton duct) orifice is found on the floor of the mouth, and the parotid (Stenson duct) is situated opposite the upper second molar. Perioral palpation can be useful to assess the extent of tumors, particularly with submandibular gland tumors. Inspection of the oropharynx for para-pharyngeal extension should be performed, which will usually manifest as the medicalization of the tonsil. Facial nerve assessment is mandatory, as is neck node palpation. A facial nerve palsy may indicate a malignant lesion with infiltration into the nerve. The head and neck skin should be checked for cancers.

Evaluation

Investigations

Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) is the primary diagnostic tool for salivary gland lesions, but the role of FNA in the diagnosis of benign and malignant salivary gland disease still carries some controversy. It is a relatively painless procedure, has few complications (seeding of the tumor does not seem to occur), and may prevent an ill-advised and often ill-fated incisional or excisional biopsy of a parotid mass. However, it is far from straightforward with issues regarding aspiration technique, adequacy of the specimen, cytological expertise, and limitations of the interpretation. If the result of FNA is at variance with other findings, then clinical judgment should prevail. It is important to be aware that false-positive results can occur, leading to misdiagnosis of malignant lesions.

Imaging

Ultrasound scan (USS) provides invaluable information about the site, size, and nature of salivary gland tumors and the presence of any significant cervical lymphadenopathy.[7] The position of a tumor in the superficial or deep aspect of the parotid gland is established by the identification of its relation to the retromandibular vein. It is usually combined with FNA (USSgFNAB), which improves the adequacy rate. In experienced hands, this can distinguish malignant from benign disease in 80% to 90% of cases. Cross-sectional imaging is not essential in straightforward benign tumors, but MRI scanning of a parotid tumor is useful in the assessment and delineation of anatomical structures, extension into the deep lobe, and relation to the facial nerve.

If the patient is suspected of having metastatic spread, the use of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET scan is useful. Recently the use of a technetium scan aided with lemon juice stimulation has been used to diagnose Warthin tumors.

Treatment / Management

Parotid Gland Tumors

Benign Tumors

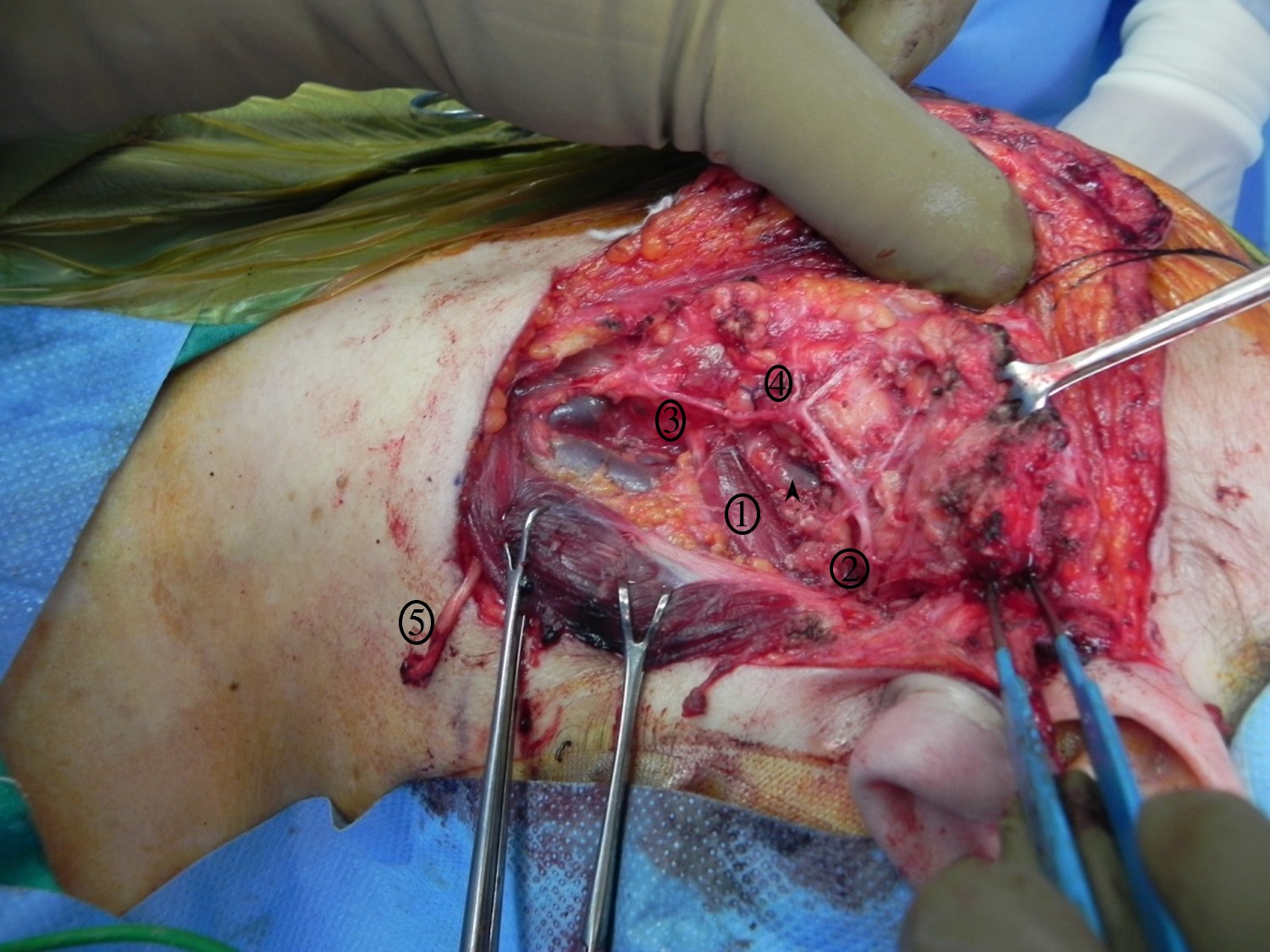

Superficial parotidectomy with identification and exposure of was traditionally the preferred procedure. The facial nerve us found 1cm inferior and 1-cm deep to the tragal pointer and bisecting the angle of the insertion of the digastric muscle into the digastric ridge. It is now generally accepted that an adequate margin in benign tumors, is a cuff of 1 to 2 mm. There is thus an increasing recognition that operations less than the traditional procedures are acceptable. Partial parotidectomy or hemi-superficial parotidectomy has become commonplace. An extracapsular dissection for benign pathology, away from the main branches of the facial nerve is an option, and even endoscopically-assisted parotidectomy can be effective in selected patients. These procedures should be undertaken by expert surgeons in carefully selected cases, e.g., small tumors confined to the superficial lobe. A "lumpectomy" is not considered an appropriate procedure due to high recurrence rates. Recurrence will occur if there has been incomplete excision and may occur if there has been tumor spillage. Complications from parotid surgery are well documented and include a scar, facial nerve injury, hematoma, seroma, salivary fistula, and Frey syndrome (gustatory sweating).

Intraoperative tumor spillage carries with it an increased rate of recurrence over a prolonged period of time, and so long-term follow-up is recommended in such cases. Adjuvant postoperative radiation therapy (RT) can be given in such cases, but this should be discussed in an interprofessional team setting. The use of RT in these cases is controversial and is sometimes not recommended, especially in younger patients due to the risk of radiation-induced tumors.

Management of a recurrent tumor is difficult. It can be multifocal, and as the facial nerve may be involved, its sheath may need to be stripped. The facial nerve should, if at all feasible, not be sacrificed; rarely, radical surgery is needed with resection of the facial nerve. The facial nerve may be encased in scar tissue, so the traditional method of finding it may have to be augmented by exposing it in the mastoid bone, or more hazardously a peripheral branch traced back. There is a high rate of transient facial nerve paresis in this group of patients. The patient should be discussed in the team for the suitability of postoperative RT to reduce recurrence.

Malignant Tumors

In small, low-grade superficial parotid tumors, a superficial parotidectomy with a margin of at least 1.5 cm may suffice, but otherwise, a total conservative parotidectomy is advised with resection of adjacent neck structures if necessary to achieve an en-bloc resection. A functioning facial nerve should be preserved unless found to be infiltrated with the tumor itself at the time of resection. If the nerve is sacrificed because of involvement, then primary nerve grafting should be performed. The greater auricular nerve as a donor is an option, but it may be involved, so the sural nerve from the leg may be preferred.

Neck dissection should be carried out in patients with clinical or radiological evidence of nodal disease. A prophylactic selective neck dissection (levels I to III) should be performed for patients with high-stage (T3/T4) disease-free clinically high-grade tumors (i.e., high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma, adenocarcinoma, squamous and undifferentiated carcinomas).

Salivary gland neoplasms respond poorly to chemotherapy, with adjuvant chemotherapy used only for palliation. Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for large tumors (greater than 4 cm), patients with incomplete or close margins, recurrent disease, perineural and vascular invasion, nodal disease, in metastatic disease, and is usually indicated for adenoid cystic carcinomas and high-grade tumors.

Differential Diagnosis

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

- Necrotizing sialometaplasia

- Pleomorphic adenoma with squamous metaplasia

- Sclerosing polycystic adenosis

Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma

- Pleomorphic adenoma

- Polymorphous adenocarcinoma

- Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma

- Basal cell adenocarcinoma

Acinic Cell Carcinoma

Staging

Staging

The classification applies only to carcinomas of the major salivary glands. Tumors arising in minor salivary glands are not included in this classification. The staging of metastatic neck nodes for salivary gland cancer is similar to that for other metastatic diseases. T-stage, according to the 8th edition of the UICC/AJCC staging manual (2016) is as follows:

- T1: Tumor 2 cm or less in greatest dimension without extra-parenchymal extension*

- T2: Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 4 cm in greatest dimension without extra-parenchymal extension*

- T3: Tumor more than 4 cm and/or tumor with extra-parenchymal extension*

- T4a: Tumor invades skin, mandible, ear canal, and/or facial nerve

- T4b: Tumor invades base of the skull, and/or pterygoid plates, and/or encases carotid artery

* Extraparenchymal extension is clinical or macroscopic evidence of invasion of soft tissues or nerve, except those listed under T4a and 4b. Microscopic evidence alone does not constitute extra-parenchymal extension for classification purposes.

Prognosis

The survival rates of patients with salivary gland cancer depend on the histological type and the stage of cancer.

The overall 5-year survival rate for salivary gland cancer is 72%.

- Stage I: The 5-year survival rate is 91%

- Stage II: The 5-year survival rate is 75%

- Stage III or IV: The 5-year survival rate varies from 39% to 65%

Consultations

Otolaryngologist

Maxillofacial surgeon

Deterrence and Patient Education

Because of the possibility of recurrence and distant metastasis, patients with a history of salivary gland, cancer must be monitored throughout their lifetime. During the follow-up care, the otolaryngologist can give patients personalized information about the risk of recurrence. Patients may have blood tests or imaging tests as part of regular follow-up care. However, testing recommendations depend on the type and stage of cancer originally diagnosed and the types of treatment given.

Pearls and Other Issues

Salivary gland cancer can be prevented by avoiding the possible risk factors namely tobacco and alcohol. For patients who work in certain industries linked with an increased risk of salivary gland cancer, taking precautions to protect themselves might help lower the risk of cancer.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Salivary gland carcinomas are a remain a heterogeneous group of tumors challenging to both pathologists and clinicians. Management of salivary gland cancer needs an interprofessional approach involving a team that consists of an otolaryngologist, a maxillofacial surgeon, a pathologist, and a radiologist.

The majority of patients first present to the primary care clinician or nurse practitioner with complaints of a painless lump. If the history and physical are suggestive of a tumor, these patients should be referred to the otolaryngologist for workup. The universal treatment for salivary gland tumors is surgery; hence, patients need to be told about the potential complication, including recurrence.

After the treatment of salivary gland carcinomas, long-term follow up is necessary to detect local and distant relapse. These patients should be followed by the oncology nurse and/or the primary care clinician for several years as there is a small risk of recurrence. Patients who relapse can be treated with palliative chemotherapy. Oncologic pharmacists are involved in the formulation, dosing, and patient education. [8][9] [Level 5]