Introduction

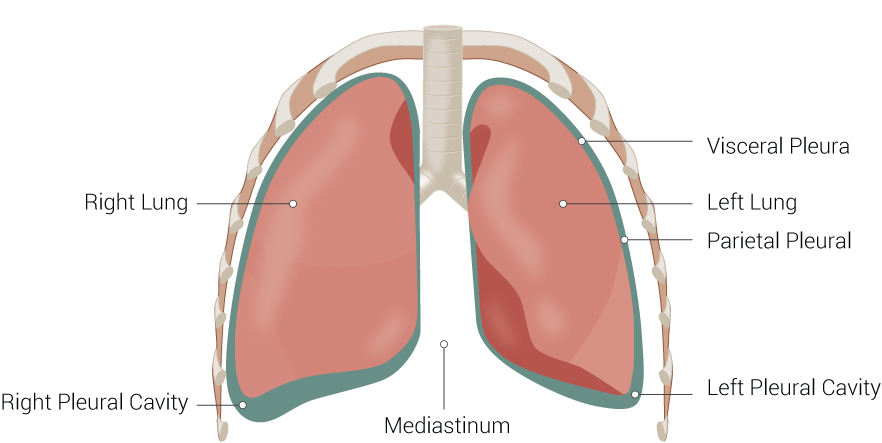

The purpose of the lung is to provide oxygen to the blood. The respiratory system divides into airways and lung parenchyma. The airways consist of the bronchus, which bifurcates off the trachea and divides into bronchioles and then further into alveoli. The parenchyma is responsible for gas exchange and includes the alveoli, alveolar ducts, and bronchioles. Lungs have a spongy texture and have a pinkish-gray hue. Also, they are anatomically described as having an apex, three borders, and three surfaces. Further, they subdivide into lobes and segments. The lung parenchyma also is covered by a pleura.[1][2][3]

Anatomy

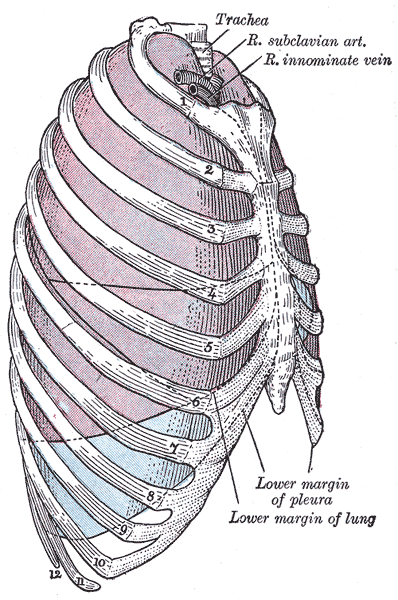

Anatomically, the lung has an apex, three borders, and three surfaces. The apex lies above the first rib.

The three borders include the anterior, posterior, and inferior borders. The anterior border of the lung corresponds to the pleural reflection, and it creates a cardiac notch in the left lung. The cardiac notch is a concavity in the lung that forms to accommodate the heart. The inferior border is thin and separates the base of the lung from the costal surface. The posterior border is thick and extends from the C7 to the T10 vertebra, which is also from the apex of the lung to the inferior border.

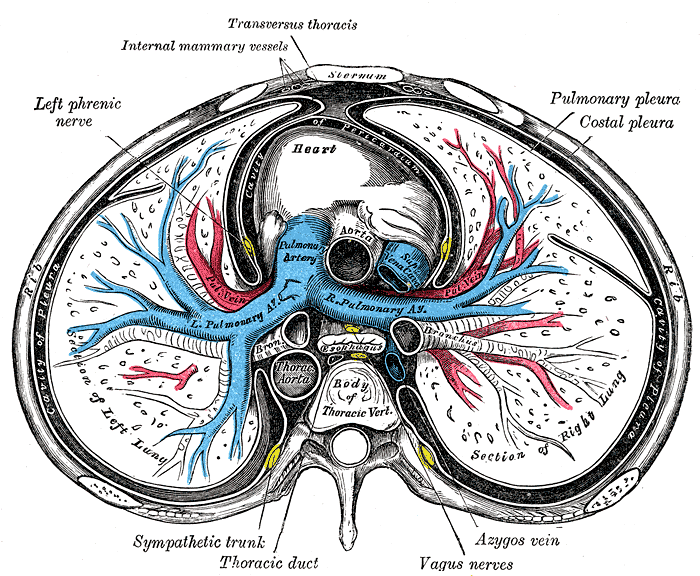

The three surfaces of the lung include the costal, medial, and diaphragmatic surfaces. The costal surface is covered by the costal pleura and is along the sternum and ribs. It also joins the medial surface at the anterior and posterior borders and diaphragmatic surfaces at the inferior border. The medial surface is divided anteriorly and posteriorly. Anteriorly, it is related to the sternum, and posteriorly, it is related to the vertebra. The diaphragmatic surface (base) is concave and rests on the dome of the diaphragm; the right dome is also higher than the left dome because of the liver.

The right and left lung anatomy are similar but asymmetrical. The right lung consists of three lobes: the right upper lobe (RUL), the right middle lobe (RML), and the right lower lobe (RLL). The left lung consists of two lobes: the left upper lobe (LUL) and the left lower lobe (LLL). The right lobe is divided by an oblique and horizontal fissure, where the horizontal fissure divides the upper and middle lobes, and the oblique fissure divides the middle and lower lobes. In the left lobe, there is only an oblique fissure that separates the upper and lower lobe.

The lobes further divide into segments that are associated with specific segmental bronchi. Segmental bronchi are the third-order branches off the second-order branches (lobar bronchi) that come off the main bronchus.

The right lung consists of ten segments. There are three segments in the RUL (apical, anterior, and posterior), two in the RML (medial and lateral), and five in the RLL (superior, medial, anterior, lateral, and posterior). The oblique fissure separates the RUL from the RML, and the horizontal fissure separates the RLL from the RML and RUL.

There are eight to nine segments on the left, depending on the division of the lobe. In general, there are four segments in the left upper lobe (anterior, apicoposterior, inferior, and superior lingula) and four or five in the left lower lobe (lateral, anteromedial, superior, and posterior).

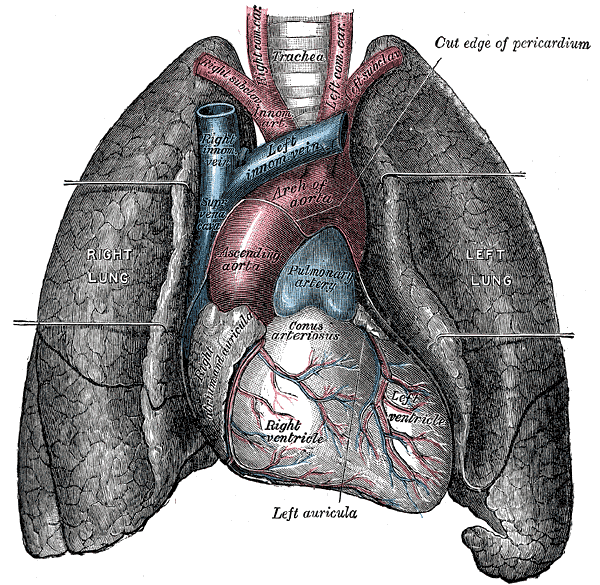

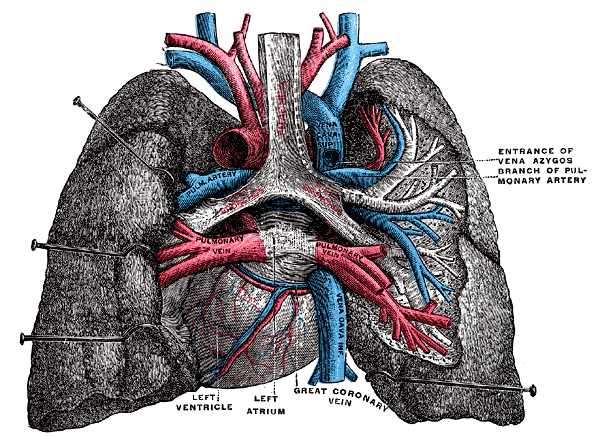

The hilum (root) is a depressed surface at the center of the medial surface of the lung and lies anteriorly to the fifth through seventh thoracic vertebrae. It is the point at which various structures enter and exit the lung. The hilum is surrounded by the pleura, which extends inferiorly and forms a pulmonary ligament. The hilum contains mostly bronchi and pulmonary vasculature, along with the phrenic nerve, lymphatics, nodes, and bronchial vessels. Both the left and right hilum contain a pulmonary artery, pulmonary veins (superior and inferior), and bronchial arteries. Also, in the left hilum, there is one bronchus, the principal bronchus, and in the right hilum, there are two bronchi, the eparterial and hyparterial bronchi. From anterior to posterior, the order in the hilum is the vein, artery, and bronchus.

Structure and Function

The function of the lung is to get oxygen from the air to the blood, performed by the alveoli. The alveoli are a single cell membrane that allows for gas exchange to the pulmonary vasculature. A couple of muscles help with inspiration and expiration, such as the diaphragm and intercostal muscles. Sternocleidomastoid and scalene muscles are used for accessory respiration when the patient is in respiratory distress or failure. The muscles help create a negative pressure within the thorax, where the pressure of the lung is less than the atmospheric pressure, to help with inspiration and filling of the lungs. Also, the muscles help with creating a positive pressure within the thorax, where the pressure of the lung is greater than the atmospheric pressure, to help with the expiration and emptying of the lung.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The main distinction is between the pulmonary artery and bronchial arteries. The pulmonary artery takes deoxygenated blood from the heart to be oxygenated by the lung parenchyma. However, the bronchial arteries provide oxygen for survival to the lung parenchyma.

The main pulmonary artery emerges from the right ventricle and bifurcates into the left and right main pulmonary arteries. The pulmonary artery branches usually trail and expand along the branches of the bronchial tree and eventually become capillaries around the alveoli. The pulmonary veins receive oxygenated blood from the alveoli capillaries and deoxygenated blood from the bronchial arteries and visceral pleura. Four pulmonary veins come together at the left atrium.

Bronchial circulation is part of the systemic circulation. The left bronchial artery arises as two (superior and inferior) from the thoracic aorta. The right brachial artery usually comes from one of the following three: the right posterior intercostal artery, with the left superior bronchial artery off the aorta or directly from the aorta. The bronchial veins collect the deoxygenated blood and empty it into the azygos vein.

The superficial and deep lymphatic plexuses drain the lung. The lymph flow from the lung parenchyma first drains into the intraparenchymal nodes and then to the peribronchial nodes. Subsequently, the lymphatics will drain to the tracheobronchial, paratracheal lymph nodes, the bronchomediastinal trunk, and then into the thoracic duct.

Nerves

The phrenic nerve comes from C3,4,5 cervical nerve roots. It innervates the fibrous pericardium, portions of the visceral pleura, and the diaphragm.

The lung receives innervation from two main sources: the pulmonary plexus (a combination of parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation) and the phrenic nerve. The pulmonary plexus is at the root of the lung and consists of efferent and afferent autonomic nerve fibers. It consists of branches of the vagus nerve (parasympathetic) and sympathetic fibers—the plexus branches around the pulmonary vasculature and bronchi. The parasympathetic innervation causes constriction of the bronchi, dilation of the pulmonary vessels, and increases gland secretion. The sympathetic innervation causes dilation of the bronchi and constriction of the pulmonary vessels.

Physiologic Variants

Accessory fissures may occur; these may be superficial or deep at the hilum. They may cause odd patterns on X-rays during specific pathologies.

Other variations that may occur can include agenesis (absence of a lung), aplasia, or accessory lobes (can cause imaging variations).

Surgical Considerations

When the entire lobe of the lung is excised, it is known as lobectomy, and the removal of just a segment is a segmentectomy. A lobectomy may be necessary when the pathology is only in one lobe and to prevent the spread of a disease, such as tuberculosis, lung abscess, emphysema, benign tumor, or lung cancer. A segmentectomy is done for benign lesions to preserve the lung or in bronchiectasis, early-stage I cancer, lung nodules, or tuberculosis.[4][5][6]

Saddle pulmonary embolism is an obstruction of the bifurcation of the pulmonary trunk. It is a surgical emergency and requires embolectomy.

Clinical Significance

Percussion of the chest is normally resonant. If there is a fluid build-up, it can become dull.[7]

On auscultation, if there is wheezing, then this is due to bronchoconstriction (asthma). If there are crackles (rales), it is possibly due to pulmonary edema (congestive heart failure, interstitial lung disease, pneumonia). If there are rhonchi, then it is due to secretions in the larger airways, causing an obstruction (chronic bronchitis, cystic fibrosis).

When reading X-rays, the lungs are black because air is translucent. Pictures come out best when the patient is inhaling.

Thoracocentesis is a procedure that uses a needle to draw out fluid from the lung. It helps to determine the cause of a pleural effusion or abscess. It can be diagnostic or therapeutic (to relieve symptoms such as pain or shortness of breath).[8]

Pneumonia is an inflammation of the lung and can cause pleural effusion. Patients may present with fever, cough, chest pain, nausea, and vomiting.