Continuing Education Activity

Low back pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal complaints encountered in clinical practice. It is the leading cause of disability in the developed world and accounts for billions of dollars in healthcare costs annually. Lumbosacral facet syndrome refers to a clinical condition consisting of various patient-reported symptoms, including mechanical back pain, radicular symptoms, and neurogenic claudication, secondary to either acute or subacute trauma or secondary to the degenerative cascade affecting the posterior spinal elements. The facet joint degenerates secondary to repetitive overuse and everyday activities, eventually leading to microinstability and synovial facet cysts that generate and compress the surrounding nerve roots. This activity reviews the etiology, presentation, evaluation, and management of lumbosacral facet syndrome and the interprofessional team's role in evaluating, diagnosing, and managing the condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the specific pathophysiology of lumbosacral facet syndrome.

- Summarize the evaluation of low back pain, including examination and imaging that would lead to a diagnosis of lumbosacral facet syndrome in cases where that is the source of pain.

- Outline the various treatment options available to manage lumbosacral facet syndrome.

- Explain the importance of interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to aid in prompt diagnosis of lumbosacral facet syndrome and improving outcomes in patients diagnosed with the condition.

Introduction

Low back pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal complaints encountered in clinical practice. It is the leading cause of disability in the developed world and accounts for billions of dollars in healthcare costs annually. Although epidemiological studies vary, the incidence of low back pain is estimated to be 5% to 10%, with a lifetime prevalence of 60% to 90%. Most occurrences of low back pain are self-limited and will resolve without intervention beyond brief periods of rest, activity modification, and physical therapy. Approximately 50% of cases will resolve within 1 to 2 weeks. Ninety percent of cases will resolve in 6 to 12 weeks.[1]

Lumbosacral facet syndrome refers to a clinical condition consisting of various patient-reported symptoms, including unilateral or bilateral back pain radiating to either one or both buttocks, sides of the groin, and thighs, stopping above the knee.[2] It should, however, be noted that in some cases, the symptoms of facetogenic pain may mimic radicular symptoms occurring from herniated discs or compressed roots. The facet joint degenerates secondary to repetitive overuse and everyday activities, eventually leading to microinstability and synovial facet cysts that generate and compress the surrounding nerve roots.[3]

The lumbar facet joint constitutes approximately 15 to 45% of low back pain, with degenerative osteoarthritis as the most common form of facet joint pain.[4] History and physical exam may serve useful in the diagnosis of facet joint syndrome, while imaging with radiographs, CT, and MRI are commonly used yet do not show an effective correlation between clinical symptoms and degenerative spine changes. Diagnostic blocks may indicate facet joints as the source of a patient's back pain, with interventions such as intraarticular steroid injection or neurolysis by radiofrequency or cryoablation to treat facetogenic pain.

Etiology

Degenerative Processes

Lumbosacral facet syndrome can occur secondary to repetitive overuse and microtrauma, spinal strains and torsional forces, poor body mechanics, obesity, and intervertebral disk degeneration over the years. This notion is supported by the strong association between the incidence of facet arthropathy and increasing age.[5] The most frequent etiology of facet joint pain is facet joint degenerative osteoarthritis, which is closely tied to degeneration of the intervertebral discs.[4] As is the case in all synovial joints, osteoarthritis involves joint space narrowing, loss of synovial fluid and cartilage, and bony overgrowth. The inflammation generated by degeneration of facet joints and surrounding tissues is believed to cause localized pain. Risk factors for lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis include age, sex, facet orientation (sagitally oriented), spinal level (L4-L5), and associated background of intervertebral disc degeneration.

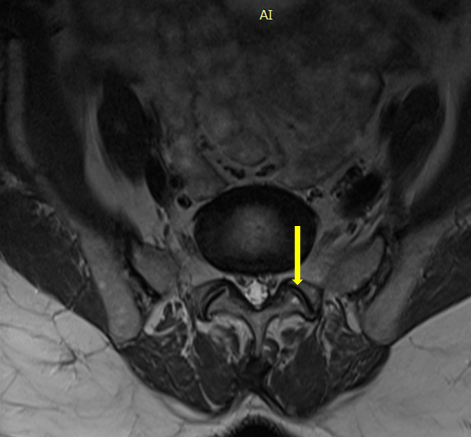

Intervertebral disc degeneration is often related to the amount of heavy work done before the age of 20. However, the association between degenerative changes in the lumbar facet joints and symptomatic low back pain remains unclear and is subject to continued debate.[6] Synovial facet joint cysts may occur in the setting of facet arthritis and may cause radiculopathy or symptomatic spinal stenosis from nerve root impingement.[7] This may lead to presentation with radicular symptoms rather than what is more often localized low back pain typical of facet joint syndrome.

Spondylolisthesis

Degenerative spondylolisthesis occurs due to the displacement of one vertebra to another in the sagittal plane. This is related in most cases of facet joint osteoarthritis and failure of segmental movement. This occurs from subluxation of the facet joints, which causes progressive loss of cartilage and articular remodeling, leading to instability and capsular tension.[8] Spondylolisthesis occurs most often at the L4-L5 level, often associated with osteoarthritis.[9] In younger patients (30-40 years old), spondylolisthesis can occur due to congenital abnormalities, isthmic spondylolisthesis, or acute or stress-related fractures. Compared to degenerative disease, L5-S1 is the most affected level and is more frequently associated with instability.

Septic Facet Arthritis

Septic arthritis is a rare etiology of facet joint syndrome.[10] An isolated form should raise suspicion for an iatrogenic cause, tuberculosis, or in one reported case, Kingella kingae.

Inflammatory Conditions

Ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis are seronegative spondyloarthropathies that may also involve the lumbar facet joints, as the facet joints are synovial in nature.[4]

Epidemiology

Low back pain is the second most significant cause of absenteeism behind upper respiratory tract infections in the workplace. Approximately 25 million people miss one or more work days due to low back pain, and more than five million are disabled from it. Patients with chronic back pain account for 80% to 90% of all healthcare expenditures.[11] The high health care costs can be attributed to multiple factors, including imaging overuse, a lack of an accurate diagnosis, work stoppages, and unwarranted surgery. Low back pain is responsible for functional limitation and can cause difficulty performing typical daily life tasks, especially in the elderly.

The cited prevalence of lumbosacral facet arthropathy is highly variable in the literature and has been listed as ranging from 5% to greater than 90%. Many of the studies investigating the prevalence of facetogenic pain used a combination of history, physical exam, and radiologic imaging, which has been shown to be relatively unreliable in establishing a diagnosis. This likely accounts for the wide range seen in estimated prevalence. A trend that has been consistent throughout studies, however, is that the prevalence of lumbosacral facet syndrome tends to increase with age. A 2004 study by Manchikanti et al. found that of 397 patients screened, 198 (50%) obtained an initial positive response to medial branch block with lidocaine. Of those patients, 124 patients (31%) reported "definite pain relief" when they received treatment with a repeat medial branch block using bupivacaine.

Pathophysiology

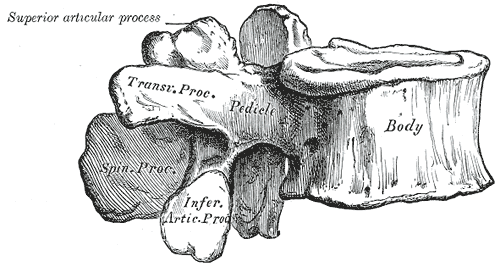

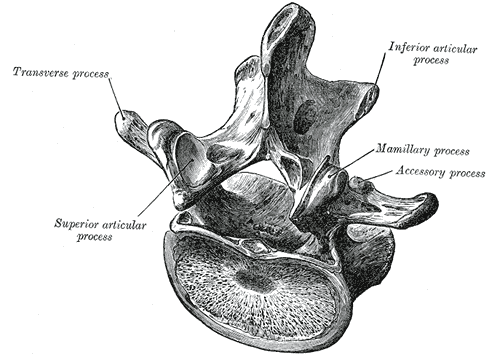

The spine consists of seven cervical, 12 thoracic vertebrae, five lumbar, five sacral, and four coccygeal bones. Each spinal segment consists of an intervertebral disc with posterior paired synovial (facet) joints comprising a "three-joint complex," where each component influences the other two, and degenerative changes in one joint lead to biochemical changes in the whole complex. Facet joints constitute the posterolateral articulation which connects the posterior arch between vertebral levels. They are diarthrodial and paired joints and are the only synovial joints of the spine, with hyaline cartilage overlying subchondral bone, a synovial membrane, and a joint capsule. The joint space has a capacity of 1 to 2 mL.[12]

The lumbar facets are composed of the inferior articular process of the vertebra above and the superior articular process of the vertebra below. The zygapophyseal joints serve to stabilize the spine and prevent injury by limiting the spinal range of motion. The facet joints are true synovial joints. The articular surface is contained in a cartilaginous sheath over an encapsulated fibrous capsule. Like other cartilaginous joints, the lumbar facets are prone to degradation over time and can cause chronic low back pain when irritated.[13] The sensory innervation of the facet is supplied by the medial branch of the posterior rami of the spinal nerve at the level of, and the level above, the facet joint. For example, The L3-L4 medial branch receives innervation from the L2 and L3 medial branch nerves. Noxious stimulation of the medial branches is caused by degenerative changes in the facet joint, which results in facet pain and lumbosacral facet syndrome.[14]

History and Physical

Low back pain and other degenerative spinal conditions can present with varying degrees of pain, disability, radiculopathy, and neurologic deficits. The clinical picture can be ambiguous for even skilled clinical practitioners.

In most presentations, facetogenic lumbosacral pain often presents secondary to chronic pain alone. It should, however, be noted that facet joint pain may be referred distally into the lower limb, thus mimicking sciatica. In these cases of "pseudo-radicular" lumbar pain, patients typically experience radiation into the unilateral or bilateral buttocks and the trochanteric region (from L4 and L5 levels), the groin and thighs (from L2 to L5), ending above the knee, and without any neurologic deficits. At times, pain may radiate further down the lower extremity reaching the foot, thus mimicking sciatic pain. This may occur especially in the setting of rather large synovial cysts causing direct mechanical compression and creating ensuing inflammation to further irritate the surrounding nerve roots.[15] Facet joint pain is typically worse in the mornings and following periods of inactivity. Stress exercise, lumbar spinal extension or rotary motions, standing or sitting positions, and facet joint palpation may also elicit lumbar facetogenic pain.[2]

In any case of low back pain, a physical examination is a key tool in determining etiology. The examination should begin with an inspection of the back to rule out any visible abnormalities. Palpation should be performed to evaluate for areas of palpable tenderness or paraspinal hypertonicity. Range of motion with active lumbosacral flexion and extension should be performed with the patient standing. While standing, lumbosacral facet loading should be performed, especially when low back pain is suspected of facetogenic etiology. This maneuver is performed by having the patient extend and rotate the spine. This increases pressure on the facet joints, thus eliciting a pain response. However, studies have shown that facet loading is unreliable in diagnosing facetogenic pain. Additionally, paraspinal muscle tenderness has been shown to be weakly associated with facetogenic pain, although this finding is considered to be non-specific.[16] After facet loading, the patient may sit down on the table to allow for the remainder of the standard neuromuscular low back examination.

Lower extremity muscle strength should be performed with hip flexion, knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion, big toe extension, and ankle plantarflexion to evaluate the L2-S1 myotomes. Light touch sensory examination should be performed throughout the L2-S1 lower extremity dermatomes. Patellar (L4) and Achilles (S1) reflexes should be elicited. Straight leg raise testing is then performed with the patient in a supine position. The examiner gently raises the patient's leg by flexing the hip with the knee in extension, with dorsiflexion as an added maneuver for test sensitivity. The test is considered positive, with pain elicited by hip flexion at an angle lower than 45 degrees, with pain typically reported as shooting down the leg.[17]

A positive straight leg raise test may be useful in the workup of lumbar facetogenic pain, as a positive test may be more indicative of radiculopathy with disc herniation rather than facet dysfunction. While in the supine position, hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABERE) can be performed. This positioning stresses the sacroiliac joint and, if positive, can point away from facetogenic etiology of back pain. Hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (FADIR) may also be performed, which indicates intraarticular hip pathology rather than lumbar facet joint pain.

Evaluation

The physical examination can be useful in ruling out other causes of chronic low back pain; however, studies have shown that physical exam is relatively nonspecific. Degenerative changes in the facet joints can be visualized in radiologic studies. Initial radiographic assessment of a patient presenting with lumbar facet-medicated pain includes AP, lateral, and oblique views.[18] Oblique radiographs are considered the best view for assessment of lumbar facet joints because of their oblique position, which generates a "Scottie dog" view. CT scan improves the anatomic evaluation of the facet joints and is thus the preferred method for imaging facet joint osteoarthritis.[19] Facet joint degeneration is characterized by joint space narrowing, sclerosis, subchondral erosions, cartilaginous thinning, joint capsule calcification, hypertrophy of articular processes, and the ligamentum flavum leading to impingement of the foramina and osteophytes. In patients with chronic low back pain, degenerative changes on CT scans are cited to range from 40% to 85%.[20]

While CT and MRI are equally useful in demonstrating morphological changes in facet joint degeneration, MRI presents the advantages of better assessing the consequences of facet joint degeneration, such as surrounding neural structural impingement.[21] Studies have shown MRI to be more than 90% sensitive and specific in visualizing facet degeneration.[22] It should, however, be noted that there is currently no consensus on how best to evaluate lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis with imaging. It has, however, been reported that in clinical practice, imaging findings of degeneration (including radiographs, CT, and RMI) have been associated with nonspecific low back pain.[23]

Radiographic changes due to osteoarthritis can be seen equally among symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, and thus radiological investigations report a poor correlation between clinical symptoms and spinal degeneration.[24] The upside of imaging in evaluating facet joint dysfunction often lies in its ability to rule out "red flag" differential diagnoses (neoplasm, cauda equina syndrome, aortic aneurysm or dissection, or fracture) rather than to prove a symptomatic facet joint arthritis.[25] Due to the poor correlation between history, physical exam, and lumbosacral facet syndrome, diagnostic blocks are considered the mainstay in establishing a diagnosis. Of note, false positive results have been documented to be as high as 25% to 40% in the lumbar spine.[26] Because of this, it is recommended that two diagnostic medial branch blocks are performed to confirm a diagnosis. A positive response is considered to be greater than 80% pain relief post-procedure.[27]

Treatment / Management

Treatment for lumbosacral facet syndrome usually includes a multidisciplinary approach. If the diagnosis is uncertain, consideration is given to performing diagnostic medial branch blocks.

Nonoperative Treatment

Nonoperative management includes oral medications such as NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and oral steroids during acute flares. Additionally, weight loss and physical therapy have demonstrated successful outcomes. [28]

Minimally Invasive Treatment

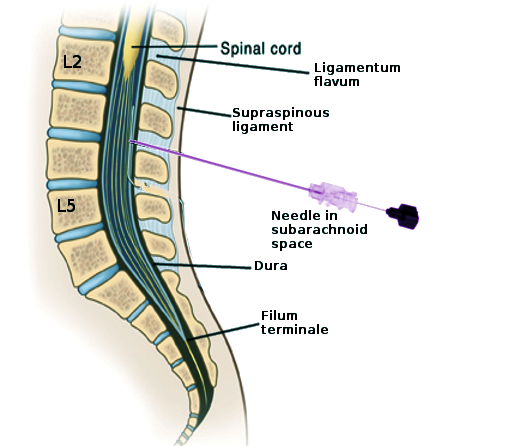

Because no concrete clinical features or diagnostic imaging studies can definitively determine if a facet joint is painful or not, medial branch nerve blocks serve as the only true diagnosis of the facet joint as the etiology of a patient's low back pain. At least 80% pain reduction and the ability to perform previously painful movements following medial branch block is considered a definitive diagnosis for facet-induced low back pain.[29] It should, however, be noted that more liberal criteria have reported greater than 50% pain relief as diagnostic.[30] A definitive diagnosis of facet joint mediate pain may require blocks at two different sessions. When performing only a single-level block, there is a high false-positive rate (30 to 45%). For this reason, many have therefore advocated for the performance of repeated blocks.[27]

A study by Cohen et al. demonstrated a success rate of lumbar facet joint radiofrequency ablation patients of 39% after a single block and 64% after two blocks.[31] Due to the dual nerve supply of the facet joints at the same level and the level above, diagnostic nerve blocks should be performed at a minimum of two levels to block a single joint.[29] Diagnostic blocks typically include local anesthesia (lidocaine and/or bupivacaine) either with or without steroids.

Following a successful medial branch block, patients may proceed with neurolysis of the medial branches. Because of the dual nerve supply of a given facet joint, radiofrequency probes should be placed at two subsequent levels. Radiofrequency (RF) and cryoneurolysis (CN) are the two most commonly used techniques. In both of these techniques, before injecting local anesthetics and thermal lesions, an electrical stimulation monitoring should be performed to ensure safety in performing the thermal denervation. While ablation may be helpful in facetogenic pain treatment, it should be noted that it does not allow for definite pain relief as the destroyed nerve will eventually regenerate, causing possible pain recurrence.[30]

In such cases, the procedure may be repeated. A prospective study by Dreyfuss et al. demonstrated that 60% of patients could expect at least a 90% pain reduction, while 87% could expect at least a 60% reduction lasting 12 months.[32] Potential side effects of radiofrequency ablation include painful cutaneous dysesthesias or hyperesthesia, neuroma formation, and increased pain due to neuritis. Unintentional spinal nerve damage causing a motor deficit is another rare complication.[33] Multifidus atrophy has also been seen following radiofrequency ablation, with more profuse atrophy following repeated ablation.

Intraarticular facet joint corticosteroid injections represent another minimally invasive treatment avenue. With the injection of inflammatory mediators into and around a degenerative facet joint, short to intermediate-term pain relief is often seen. It should, however, be noted that discrepancies persist in the literature regarding the efficacy of steroids for facet joint pain.[34]

For the above minimally invasive techniques, imaging guidance has been shown to both increase the technical and clinical efficacy of the procedure and reduce potential complications. Common complications of all facet joint procedures include bleeding, infection, and vasovagal syncope.[35]

Surgical Treatment

- Indications for surgical intervention include:

- Symptoms refractory to nonoperative modalities (e.g., 3 to 6-month trial)

- Large associated synovial facet cyst correlating with clinical exam and presentation

- Laminectomy with decompression is the classic first-line treatment for symptomatic, intraspinal synovial cysts

- The literature also supports the utilization of facetectomy, decompression, and instrumented fusion (as opposed to a simple "lami decompression")

Differential Diagnosis

- Lumbosacral discogenic pain syndrome

- Lumbar disc herniation

- Lumbosacral facet syndrome

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy

- Lumbosacral spine acute bony injuries

- Lumbosacral spine sprain/strain injuries

- Lumbosacral spondylolisthesis

- Lumbosacral spondylosis

- Paraspinal muscle/ligament sprain/strain

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Seronegative spondyloarthritis (most commonly ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and reactive arthritis)

- Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

- Infection

- Neoplasm

- Fibromyalgia

- Intraarticular Hip Pathology

- Piriformis syndrome

- Sacroiliac joint injury

While at times difficult, an attempt should be made to differentiate lumbosacral facet joint syndrome from the above diagnoses at first with a history and physical examination. While a history of pain radiation to the lower extremity can point more towards radiculopathy or discogenic pain, providers should remember that such presentation may also indicate facetogenic pain, especially in facet joint cysts. Physical examination, while not always completely specific, may help point away from certain diagnoses in the differential. Pain with hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation (FABERE) and hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (FADIR) may point more towards sacroiliac and intraarticular hip pathology, respectively. A positive straight leg raise test may point more towards lumbosacral radiculopathy or discogenic pain. However, these tests are often nonspecific. While imaging with X-ray, CT, and MRI may be useful in evaluating spinal anatomy, these tests are also often nonspecific in diagnosing the true etiology of pain. Lumbar medial branch block, therefore, serves as the most reliable definitive diagnosis of the facet joint as the true etiology of a patient's low back pain.

Treatment Planning

When history and physical examination indicate lumbosacral facet syndrome, treatment should be initiated with physical therapy and medication if needed. Physical therapy includes lumbosacral stretching and strengthening, as well as core strengthening. Therapeutic modalities, including heat, ice, deep tissue massage, myofascial release, and ultrasound treatment, may also prove useful in the symptomatic treatment of low back pain secondary to facet joint dysfunction. Medication treatment regimens for lumbosacral facet joint syndrome may start with acetaminophen or the physician's choice of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication.

If the patient's pain persists despite these measures, or if the patient is unable to tolerate therapy due to the severity of their pain, the patient should be evaluated for minimally invasive interventions, either with medial branch block followed by radiofrequency ablation if successful or with intraarticular facet joint injection. Surgical treatment should be referred for severe pain refractory to the above management and may include laminectomy, facetectomy, decompression, or instrumented fusion.

Prognosis

Lumbosacral facet joint syndrome will increase with age, especially when secondary to its most common cause of facet joint osteoarthritis. Conservative treatments, including physical therapy, should serve as first-line management. Patient's who fail conservative treatment with physical therapy and medications may undergo a diagnostic medial branch block indicative of facetogenic etiology of pain. In patients with successful diagnostic blocks, radiofrequency ablation has been shown to relieve pain for six months up to 1 year, at which time repeat neurolysis may be performed if indicated.

Complications

Serious complications of interventions used in treating lumbosacral facet joint syndrome are rare. Any intraarticular steroid injection carries a risk of metabolic and endocrine adverse effects related to elevations in glucose levels and suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal access. There have been case reports detailing infection following intraarticular steroid injection. Such infections have included epidural abscess, septic arthritis, and meningitis. Other complications of spinal injections include dural puncture and spinal anesthesia. The most common reported complication of radiofrequency ablation is neuritis, occurring with a reported 5% incidence.[36] It should be noted that there have also been reports of transient numbness and or dysesthesias, with other rare complications including burns resulting from electrical faults.

Deterrence and Patient Education

As part of physical therapy as an initial treatment, patients should be educated regarding home exercises, as well as proper posture. Given the correlation between obesity and the development of lumbosacral facet joint dysfunction, weight loss counseling serves as an important tool in preventing the development of facetogenic pain. Patients should seek professional evaluation from an orthopedist, a physiatrist, or a spinal surgeon, to receive a thorough evaluation to rule out more serious "red flag" etiologies of low back pain prior to implementation of a proper treatment plan.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A strong relationship between the clinician and the patient is imperative for improving healthcare outcomes. Good communication among an interprofessional team is key, which may include an orthopedist, pain medicine physician, physiatrist, spinal surgeon, primary care clinician, physical therapist, dietician, and nurse. Lumbosacral facet joint syndrome may cause debilitating pain without proper management. Modifiable risk factor management, physical therapy, and medication management should serve as first-line treatment. Interventional procedures for facet-mediated pain, including radiofrequency neurotomy and intraarticular block, carry level I and II evidence, respectively. The overall outlook for patients with low back pain is often poor, with relapse of pain common following any treatment.