Continuing Education Activity

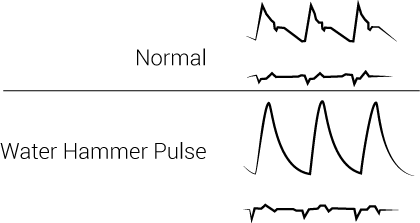

Water hammer pulse is a physical exam finding that describes a bounding, forceful pulse with a rapid upstroke and descent. It is seen in many physiological and pathological conditions. Etiology can either be either be physiologic or pathologic. Water hammer pulse can be related to hyperdynamic circulatory states or cardiac lesions, but it is most commonly associated with aortic regurgitation. This activity describes the evaluation of patients with water hammer pulse and reviews the etiology-based management of these patients. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with pathologic causes of water hammer pulse.

Objectives:

- Describe the method for eliciting a water hammer pulse.

- Outline the pathophysiology of water hammer pulse.

- Review the most common causes of water hammer pulse.

- Outline the importance of collaboration among the interprofessional team in the evaluation of patients with water hammer pulse.

Introduction

Water hammer pulse is a physical exam finding that describes a bounding, forceful pulse with a rapid upstroke and descent. It is seen in many physiological and pathological conditions but is most often associated with aortic regurgitation. In 1833, Dr. Dominic John Corrigan first described the water hammer pulse when he saw the visible sudden distention and collapse of the carotid arteries in patients with aortic regurgitation. Dr. Thomas Watson further investigated this palpable pulse in 1844. He compared the findings to the pulse felt when playing with a water hammer toy. During the Victorian era, a water hammer was a toy in which a tube was filled halfway with fluid, and the rest would be a vacuum. The tube could be continuously inverted, and the sound of the impact would sound like a hammer blow. [1]

Etiology

Etiologies can be physiological or related to hyperdynamic circulatory states or cardiac lesions.

Physiological etiologies include:

Hyperdynamic circulatory states include:

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Anemia

- Paget disease

- Liver cirrhosis

- Thiamine deficiency or beriberi

- Systolic hypertension

- Arteriovenous fistula

- Cor pulmonale

Cardiac lesions include:

- Aortic regurgitation

- Patent ductus arteriosus

- Aortopulmonary window

- Sinus of Valsalva rupture

- Leaking aortic valve prosthesis

- A ventricular septal defect with aortic regurgitation

- Truncus arteriosus

- Mitral regurgitation

- Complete heart block

Epidemiology

Aortic regurgitation is the most common condition associated with the water hammer pulse. According to the Framingham study, the prevalence of aortic regurgitation was 4.9%, with moderate or severe regurgitation occurring in 0.5%. Aortic regurgitation is more common in men than in women. Clinical manifestations of the disease peak between the fourth and sixth decades of life. [2]

Pathophysiology

In physiological and hyperdynamic circulatory states, the fall in systemic vascular resistance and increased cardiac output causes the water hammer pulse.

The pathophysiology in patients with aortic regurgitation is different. An increased stroke volume filling the relatively empty arterial vessels causes the rapid upstroke when feeling the water hammer pulse. This increased stroke volume is secondary to an increase in end-diastolic volume from the retrograde blood flow from the aorta into the left ventricle during ventricular diastole, or relaxation. The rapid downstroke is partly due to two causes. The first cause is the sudden fall in diastolic pressure in the aorta, which is due to regurgitation of blood from the aorta, or “aortic run-off,” into the left ventricle through the leaky valve. The second cause is the rapid emptying of the arterial system.

The decrease in diastolic pressure from the regurgitant flow also causes an increase in pulse pressure. Pulse pressure is the difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure. Compensation for the decrease in diastolic pressure occurs in two ways. First, due to the regurgitant fraction of blood flow, the heart undergoes chamber dilation and eccentric hypertrophy. These effects increase the stroke volume and therefore the systolic pressure. Secondly, the sympathetic nervous system releases catecholamines and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis works to increase cardiac output to try to maintain a normal mean arterial pressure. As aortic regurgitation continues to progress and worsen, the systolic pressure and pulse pressure continue to rise. Increasing these pressures accentuates the water hammer pulse. However, as the left ventricle continues to stretch, and with the resultant cardiac remodeling, systolic heart failure eventually develops. Systolic heart failure results in stroke volume decrease and forward blood flow. [1]

History and Physical

The history will be vital in determining the etiology of the water hammer pulse. For example, alcohol abuse in a patient with the water hammer pulse sign could lead to the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Getting a detailed extracardiac history can help diagnose conditions such as anemia, thyrotoxicosis, fever, pregnancy, cirrhosis, Marfan, rheumatological disorders, and syphilis. A detailed cardiac history, especially regarding congenital heart diseases, will be necessary when suspecting long-term valvular or septal defects. [1]

The fundamental principle of eliciting the water hammer pulse is to elevate the patient's arm above the heart and to palpate the patient's forearm with the examiner's palm. The first step is to place the patient in a supine position at a slight recline. With the examiner’s hand wrapped around the patient’s wrist, the radial pulse is palpated. The patient’s arm is then raised above the patient’s head. The water hammer pulse will feel like a tapping impulse through the patient’s forearm due to the rapid emptying of blood from the arm during diastole, with the help of gravity's effects.

Evaluation

The history and physical exam findings will guide which laboratory tests and imaging to order to determine the etiology of the water hammer pulse. Examples may include testing thyroid-stimulating hormone or T4 in a patient with suspected thyrotoxicosis, a urine pregnancy test in a woman of childbearing age, genetic testing for Marfan, rheumatological blood work for collagen vascular diseases, complete blood count for anemia, and abdominal ultrasound for cirrhosis.

Chronic aortic regurgitation is one of the more common causes of the water hammer pulse. Therefore, echocardiography such as a transesophageal echocardiogram may be necessary. Examination of the anatomy of the valve, quantifying the amount of aortic regurgitation, defining aortic morphology and size, and evaluating the mechanism of regurgitation between types 1 to 3 will be essential. These actions are particularly helpful to determine whether surgery or valve repair is necessary.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for the water hammer pulse is dependent on the etiology.

Chronic aortic regurgitation is one of the common causes of the water hammer pulse. Thus, knowing the most up-to-date recommendations on aortic valve repair or replacement will be crucial. The 2017 European Society of Cardiology/European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease outline the indications for intervention in chronic aortic regurgitation. These guidelines depend on the size of the ascending aorta, the severity of the regurgitation, patient symptomology, and the left ventricular function. For patients with severe aortic regurgitation, surgery is indicated in certain patients of classes 1B and 1C. These class 1B patients include symptomatic patients and those with a resting left ventricular ejection fraction less than or equal to 50%. Candidates from class 1C include patients undergoing a coronary artery bypass graft or surgery of the ascending aorta or another valve. In individuals who are asymptomatic with normal left ventricular function, regular evaluation of left ventricular function with serial echocardiograms and changes in patient exercise tolerance will be essential to identify the necessity for surgery. [3]

Differential Diagnosis

Pearls and Other Issues

The water hammer pulse is a physical exam finding with many different etiologies. However, it is commonly associated with aortic regurgitation. It will feel like a tapping impulse through the patient’s forearm due to the rapid emptying of blood from the arm during diastole. Obtaining a detailed history and physical exam will be essential in determining the diagnosis. Most of the hyperdynamic circulatory states and physiological causes can be diagnosed based on the extracardiac history and symptomology. Echocardiography may be necessary if a cardiac lesion is suspected. Knowing the current guidelines for aortic valve repair or surgery is essential if defects in the aortic valve or aorta are present.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare workers including the nurse practitioner should be familiar with some of the signs associated with aortic regurgitation. The water hammer pulse is most often found in patients with AR but can also be observed in several other conditions. If a water hammer pulse is identified, the next step is to obtain an ECHO and rule out AR. All patients with AR need close follow up with a cardiologist. Asymptomatic patients with normal heart dimensions can be followed for many years. Symptomatic patients and those with enlarging cardiac dimension should be referred to a cardiac surgeon for valve replacement.