Continuing Education Activity

Diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (DPGN) is a common and serious histological form of renal injury seen commonly in those suffering from autoimmune diseases. It advances into rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with crescents at an accelerated rate and hence if not timely, diagnosed and treated can end up as end-stage-renal disease. It is vital to carry out a renal biopsy to understand the underlying etiology better and know the severity and chronicity of the disease. This activity will review the care provided by an interprofessional team.

Objectives:

- Outline the etiology, possible related auto-immune diseases, and identify the prevalence of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis.

- Describe the appropriate presentation, signs, and symptoms of a patient with diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis.

- Summarize the most commonly used treatment regimens and the follow-up tests involved in showing the efficacy of the treatment of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to diagnose diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis earlier and prevent long-term complications thereby decreasing morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Glomerulonephritis is a term used to describe varying degrees of glomerular injury associated with an activated inflammatory process. This, combined with increased cellular proliferation and involvement of more than 50% of glomeruli, makes it diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (DPGN), which can present with either nephrotic or non-nephrotic range proteinuria as well as hematuria. DPGN encompasses immune disorders with subsequent renal involvement due to either immune complex deposition or direct formation of antibodies causing cellular injury with sclerosis, fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and necrosis visible on renal biopsy.

Etiology

The etiology of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis stems from the type and location of deposits seen on renal biopsy; the most commonly associated disease is systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Class IV of lupus nephritis shows a diffuse pattern on microscopic examination. In addition, the renal involvement seen in IgA nephropathy, anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) antibody disease, pauci immune vasculitis like granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Henoch-Schonlein purpura all show a histological pattern indicative of DPGN. Some forms of post-infectious glomerulonephritis, especially those associated with chronic infections like endocarditis, hepatitis B, and C, show a diffuse involvement of glomeruli with increased cellular proliferation.[1]

Epidemiology

Most cases of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis are associated with SLE or IgA nephropathy. About 38% of those with SLE go onto developing end-stage renal disease (ESRD).[2]Studies have shown that 8.6% of those diagnosed with lupus nephritis died while 95% had a 5 years mean survival rate after diagnosis. Other studies have shown that 4.8% of those with IgA nephropathy had diffuse granular deposits within the mesangium. As per Japanese studies, in those undergoing renal allograft transplants, 16.1% had mesangial IgA deposition.[3][4] Nephritis associated with anti-GBM disease is a rare occurrence, as shown by studies conducted in Australia and New Zealand, with only 0.8% out of all patients with ESRD attributed to it.[5]

Pathophysiology

The mechanism of injury involved varies according to the underlying etiology. It usually involves the deposition of immune-complexes (antigen-antibody complex), which activates the classic pathway of the complement system.C1q undergoes conformational change resulting in C3 convertase being formed which breaks C3 into C3a and C3b. The activated complement system and chemotactic factors like C3a, C5a, and IL-8 recruit polymorphonuclear cells and leukocytes. These release interleukins like IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interferon-gamma that bring about cellular injury. Activated platelets cause mesangial proliferation. Immune-complexes are a combination of DNA, anti-dsDNA ubiquitin, and other proteins in DPGN associated with lupus nephritis. Elsewhere deposition of complements like C3 and C4 are associated with auto-immune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis, and dermatomyositis. Another mechanism of injury involves direct antibodies being formed against the alpha-3 chain of collagen-IV as seen in anti-GBM disease and their deposition in the subepithelial spaces. This damages the basement membrane leading to loss of negative charge resulting in proteinuria. The location of deposits also depends on the size and the charge of these. Anionic deposits fail to cross the membrane and get deposited in the mesangium and endothelial spaces, while cationic deposits can cross and are usually present in sub-epithelial spaces. In a more advanced form of the disease, crescents are formed (a combination of epithelial cells, activated macrophages, and fibrin); they cause obliteration of small blood vessels leading to necrosis and sclerosis. Vasculitis is associated with the presence of fibrinoid necrosis within the vessel walls of the glomeruli.[6][7]

Histopathology

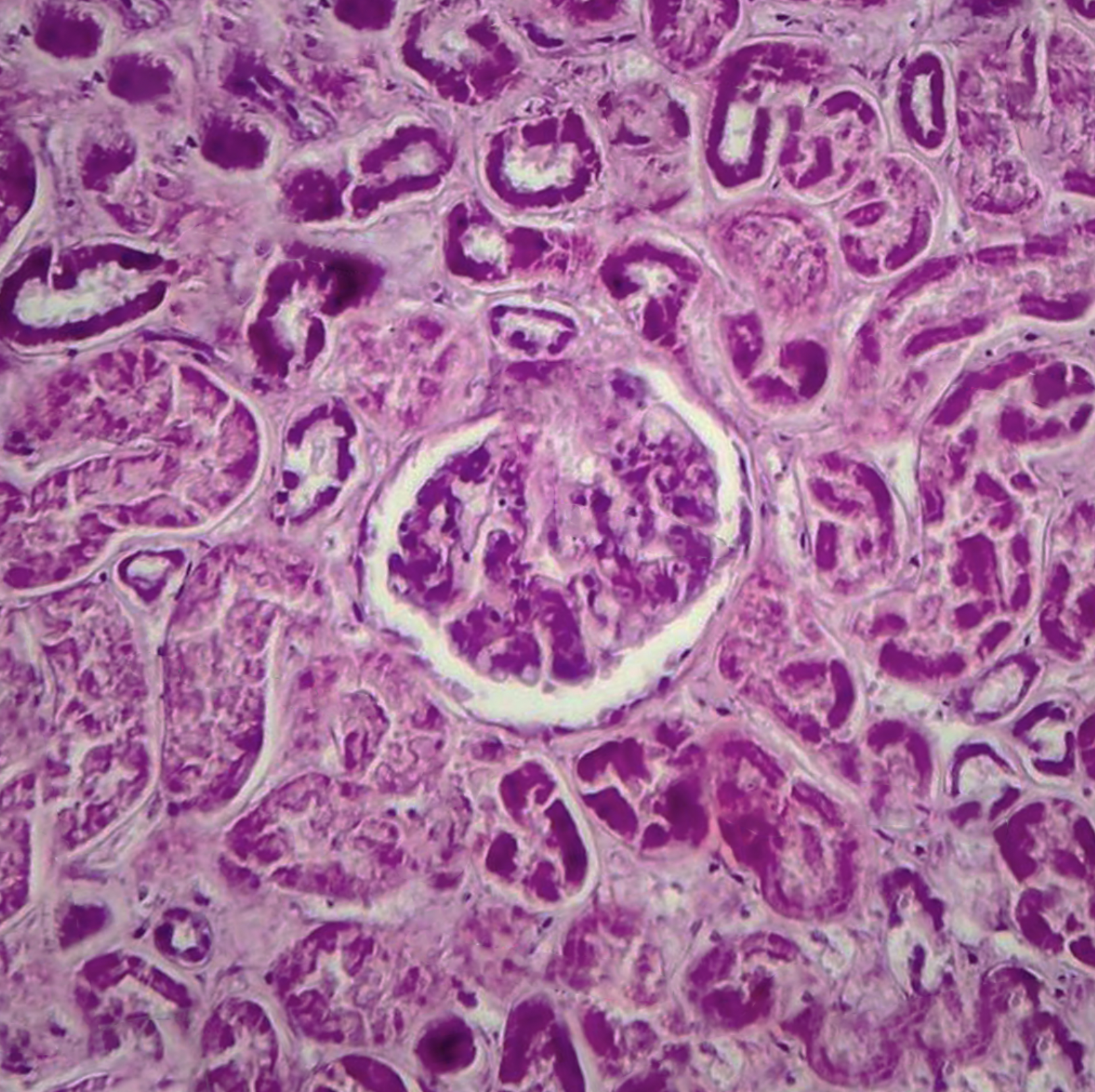

Histological features of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis are described on the basis of light microscopic, electron microscopic, and immunofluorescence findings of renal biopsy. Light microscopy shows increased cellular proliferation of either the endo-capillary or the mesangium along with inflammatory cell infiltration. Based on these findings, DPGN is categorized as either (1) diffuse endocapillary or (2) diffuse mesangial PGN. A comparison of the two shows that there are increased sub-epithelial depositions with a worse prognosis seen in the former. In a more severe form of the disease, sclerosis, fibrosis, as well as atrophy, is visible along with the involvement of the interstitium.[8]

The characteristic wire-looping pattern of capillary walls is also noted. Electron microscopy shows the precise location of these electron-dense deposits. These deposits can be present in the subepithelial, subendothelial, or intramembranous spaces. In some cases, there is the involvement of the tuboreticular spaces. Immunofluorescence findings are indicative of the etiology of DPGN as in anti-GBM disease, it shows linear deposits along the basement membrane, while in others it shows granular deposits of immune-complex. Staining also shows the presence of immunoglobulins, fibrin, or complements or the absence of these, as seen in pauci-immune ANCA-related DPGN. It can also show which immunoglobulin is present as in IgA immunoglobulins seen in IgA nephropathy or IgG4 or IgG1 seen more commonly in DPGN associated with lupus nephritis or IgG, IgM, C3, and C1q seen in others. A renal biopsy finding also tells about the chronicity, severity, and extent of renal damage depending on the presence of crescents, necrosis, or exudative lesions.[9][10][11]

History and Physical

Patients can have varying presentations ranging from generalized systemic symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and fatigue, indicating underlying uremia. Some can present with hypertension, decreased urine output, frothy urine due to proteinuria, generalized body swelling, pedal edema, and microscopic or gross hematuria. Patients with IgA nephropathy (Berger disease) may present with the classic findings of flank pain and gross hematuria following upper respiratory infections. Others with underlying autoimmune diseases resulting in DPGN can present with photosensitivity, rash, joint pains, serositis, oral ulcers, while those with an underlying anti-GBM disease can have alveolar hemorrhage and respiratory signs and symptoms.

Evaluation

A complete blood count showing possible anemia and low platelet count followed by renal function tests with elevated serum creatinine (0.4 mg/dl above the upper limit), blood urea nitrogen levels, and urine analysis positive for urine sediments: red blood cells and casts, white blood cells, granular casts are indicative of a glomerular pathology. For further confirmation, a 24 hours urine protein to creatinine ratio and 24 hours urine sample for protein levels can be done. A protein count of greater than 3.5 g/day is suggestive of nephrotic range proteinuria, which is associated with a worse prognosis. A 24-hour urine sample can be used to calculate creatinine clearance to estimate the eGFR. Renal ultrasound can be done to see the size and confirm the presence of two kidneys and the absence of any obstructive pathology resulting in hydronephrosis. Serum complement (C3 and C4) levels help determine the etiology; low levels are associated with the presence of SLE, cryoglobulinemia, and infectious etiology.[12]

Renal biopsy remains the gold standard diagnostic test with light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence study, giving information regarding the severity and chronicity of the disease. Further insight into the possible underlying pathology can be achieved from auto-antibody screening (DS-DNA antibody, ANA, p-ANCA, c-ANCA, anti-GBM antibodies) as well as hepatitis B and C and HIV serology to rule out chronic infections.

Treatment / Management

Treatment modalities depend on the severity of the disease. Those with a milder form of the disease with mild, non-nephrotic range proteinuria, normal serum creatinine levels, and normal eGFR can be treated conservatively with only ACE inhibitors with a 3 to 6 months regular follow up to assess disease progression. Statin inhibitors are also added due to the increased rate of atherosclerosis and possible cardiac involvement seen in those with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Those with a greater degree of glomerular disease, hematuria, hypertension, increased serum creatinine and decreased eGFR are treated with corticosteroids at 1 mg/kg/day with a maximum dose of 60 to 80 mg/day for 12 to 16 weeks. The dose of steroids is then tapered off. If the patient is non-responsive to steroids or cannot tolerate them, then calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus (0.04 to 0.08 mg/kg/day) can be added.

Lupus nephritis is said to be in its active phase if its class III or IV and its treatment are divided into induction and maintenance phases. Some studies have shown that a combination of methotrexate and intravenous cyclophosphamide pulse therapy is associated with increased positive outcomes for refractory diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. In some severe cases, cyclophosphamide at 2 mg/kg/day has been added to steroids, and the dose is then tapered down to 1.5 mg/kg/day.[13] Mycophenolate mofetil at 300 mg/m/day slowly increased to 1000 mg/ m/day for 24 months has also shown positive outcomes in some cases. Others have shown that diffuse PGN associated with lupus nephritis can be treated with a combination of double filtration plasmapheresis and methylprednisolone (0.8 to 1.0 mg/kg/day) with accelerated remission of the diseases, decreased chances of recurrence, and complement levels within the normal range. These people also showed no plasmapheresis-related side effects.[14]

Anti-GBM disease has shown great response to treatment with a combination of pulse methylprednisolone, two weeks of plasmapheresis followed by two months of corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide.[15] Immunosuppressive therapy efficacy can be indicated by measuring urinary macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF).[16] It is a proinflammatory cytokine that causes the activation of macrophages, and its high urinary levels are associated with a good prognosis.[17][18]

Differential Diagnosis

The presentation of all different types of glomerulonephritis is the same. They can be differentiated only on the basis of specific renal biopsy findings. Therefore, a patient presenting with hematuria is classified under nephritic syndrome, which can include acute glomerulonephritis, diffuse proliferative, focal proliferative, or membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. The precise diagnosis is based on if more than 50% glomeruli are involved; it is termed diffuse, while less than 50% glomeruli involvement makes it focal. Thickening of the basement membrane indicates membranous, while increased cellularity is indicative of proliferative etiology. In case cellular damage is extensive enough to result in greater than 3.5 g/day proteinuria, it is then classified as nephrotic syndrome.

Prognosis

The outcome of diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis depends on the stage at which the patient gets diagnosed with the disease. Renal biopsies with a greater extent of tubule-interstitial injury with inflammation atrophy and fibrosis and the presence of crescents have been associated with worse outcomes. Moreover, factors affecting the survival percentage included the degree of proteinuria, serum creatinine levels, blood urea nitrogen levels, and eGFR at the time of presentation.[19] Accelerated hematuria, presence of hypertension, and hypoalbuminemia are also considered bad prognostic features. Males are thought to have worse outcomes compared to females. Studies have shown that IgA nephropathy is linked with the best outcome, while lupus nephritis is the reason for high mortality and morbidity in those with SLE while 10% of those with lupus nephritis go onto develop end-stage renal disease.[20] Low levels of complement are considered a poor serological indicator of disease prognosis.[21]

Complications

As such, complications are associated with a delay in the diagnosis of the disease leading to extensive glomerular damage causing the progression of proteinuria into a nephrotic range followed by hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, and clotting disorders due to loss of anti-thrombin III. A delay in the diagnosis and treatment can result in progression into rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with crescents. Furthermore, renal biopsy is related to post-procedural complications like bleeding, arterio-venous fistula, peri-renal soft tissue infection, and prolonged pain. Late diagnosis is also linked with progression into chronic renal disease (stage V) or end-stage renal disease with eGFR less than 15 ml/min requiring a patient to have lifelong hemodialysis sessions.

Deterrence and Patient Education

In all those people who are diagnosed with autoimmune diseases, it is essential to educate them on the signs and symptoms of developing renal disease. They need to be educated on lifestyle modifications like weight reduction, decreased amount of salt in the diet, and increased fiber intake as these are linked with decreasing the probability of developing hypertension, which in turn leads to renal impairment. Moreover, once the disease is diagnosed and treatment is started the importance of regular follow-up should be emphasized. Early diagnosis and treatment compliance are the only ways to prevent a patient from undergoing hemodialysis for life.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

With having the best outcome of the disease as the aim, an inter-disciplinary approach is required where the physician, pathologist, and possibly the renal transplant team all collaborate. Once a patient is diagnosed with DPGN, the severity of the disease is assessed, and the need for a possible renal transplant is evaluated. Studies have shown that renal allograft transplants are associated with the recurrence of de-novo glomerulonephritis. Patients are required to be educated regarding the importance of medication compliance as well as the possible side effects of immuno-suppressant therapy. The possibility of relapse and no response to treatment should be communicated to the patient, along with the possibility of needing life-long hemodialysis.