Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Blood Supply to the Abdomen

The abdominal arteries arise from the abdominal aorta, which enters the abdomen through the aortic hiatus of the diaphragm near T12 and descends, left to the inferior vena cava and anterior to the vertebral bodies. Before its bifurcation at L4 vertebra, the aorta gives off the renal arteries and the three major trunks which supply the alimentary organs.[3]

Branches of the Abdominal Aorta

The branches of the abdominal aorta include three major unpaired trunks (celiac trunk, superior mesenteric, inferior mesenteric arteries), six paired branches, and an unpaired median sacral artery.

The other method of classifying the abdominal aorta branches are as follows:

Ventral branches: Coeliac trunk, superior mesenteric and inferior mesenteric arteriesLateral branches: Inferior phrenic, middle suprarenal, renal and gonadal arteriesDorsal branches: Lumbar and median sacral arteriesTerminal branches: Right and left common iliac arteries

The first branches off of the abdominal aorta are the paired inferior phrenic arteries, which further branch into superior suprarenal arteries.

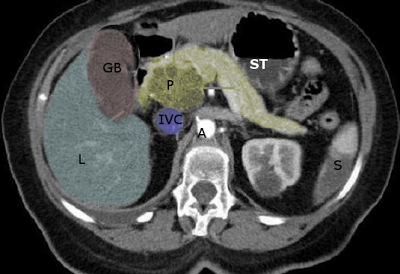

The second of the branches of the abdominal aorta is the unpaired celiac trunk. The celiac trunk (L1) supplies the foregut, which consists of the esophagus, stomach, proximal half of the duodenum, the gallbladder, superior portion of the pancreas and liver. The celiac trunk is found posterior to the stomach and lesser omentum. Three major branches of the celiac trunk include the common hepatic artery (further branches into the proper hepatic, right gastric, and gastroduodenal arteries), left gastric artery, and splenic artery.

The third branches are the paired middle suprarenal arteries.

The fourth branch is the unpaired superior mesenteric artery. The superior mesenteric artery provides oxygenated blood to the midgut; this includes the distal half of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, right colic flexure, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon.

The fifth branches are the paired renal arteries, which give rise to the inferior suprarenal arteries. The renal arteries arise around L1/L2 and supply the kidneys on either side. The renal artery further subdivides into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch further divides into four segmental arteries that supply renal tissue.

The lumbar arteries follow the renal arteries, and the first through fourth are in pairs. There is also a set of paired testicular or ovarian arteries that supply the gonads in males and females, respectively.

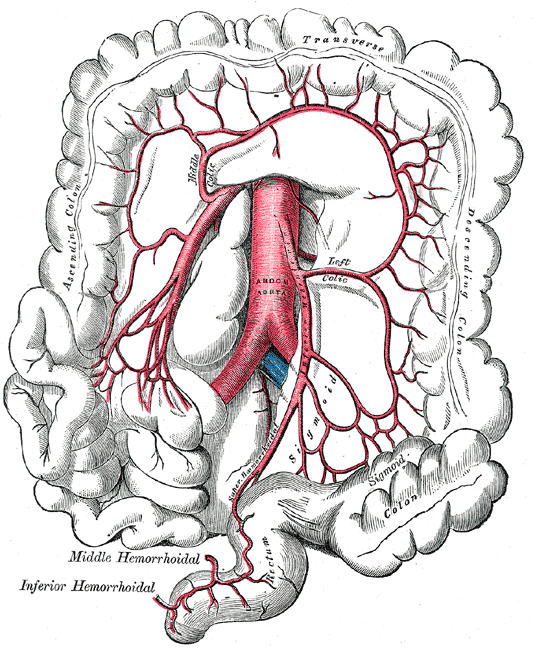

The third unpaired branch of the abdominal aorta is the inferior mesenteric artery. The inferior mesenteric artery arises around L3 and supplies the hindgut structures: the distal half of the transverse colon, the left colic flexure, the descending and sigmoid colons, rectum, and upper anal canal.

The last paired branches of the abdominal aorta are the common iliac arteries, which course down into the pelvis to supply the pelvis and lower limbs.

The small unpaired offshoot branch is the median sacral artery.

All the above arteries are well arranged to provide adequate blood flow to the richly vascularized organs of the abdomen. Three major arterial anastomoses of the abdomen exist. The first is between the celiac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery via the pancreaticoduodenal arteries. The second exists between superior and inferior mesenteric arteries via the middle and left colic arteries. The third causes anastomosis between the inferior mesenteric and internal iliac arteries via the superior and middle or inferior rectal arteries.

Abdominal arterial anastomoses

Arterial Supply Distal to the Aortic Bifurcation

Close to the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra, the abdominal aorta bifurcates into the right and left common iliac arteries. From there, each common iliac artery runs inferolateral and further subdivides into the external and internal iliac arteries on each side. The external iliac artery then descends into the iliac fossa and becomes the femoral artery posterior to the inguinal ligament.

Arterial Supply to the Pelvis

The internal iliac artery is the major blood supply to the pelvis.

The anterolateral abdominal wall has an intricate supply of arteries and veins. The main vessels are the superior epigastric vessels and branches of the musculophrenic vessels. Then we have the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac vessels coming from the external iliac vessels. Next, are the superficial circumflex vessels and superficial epigastric vessels which come from the femoral artery and greater saphenous vein. Last is the posterior intercostal vessels and the branches of the subcostal vessels. The vessels of the anterolateral abdominal wall are arranged circumferentially, just like the intercostal vessels. The vessels of the central abdominal wall, on the other hand, are oriented vertically. The superior epigastric artery is a continuation of the internal thoracic artery. It supplies the superior part of the rectus abdominis and connects with the inferior epigastric artery at the level of the umbilicus. The inferior epigastric artery comes from the external iliac artery. It also supplies the rectus abdominis muscle. The musculophrenic artery also comes from the internal thoracic artery and supplies the anterolateral part of the diaphragm. The deep circumflex artery comes from the external iliac artery and supplies the iliacus muscle. The femoral artery has two branches, namely the superficial circumflex iliac artery, which supplies the superficial abdominal wall in the inguinal area, and the superficial epigastric artery which supplies the superficial abdominal wall in the pubic region.[4]

The abdominal wall will ultimately drain into the superior vena cava via the internal thoracic vein medially and on the lateral areas, the lateral thoracic veins. The other site of drainage goes inferiorly to the inferior vena cava, and this is through the superficial and inferior epigastric veins.

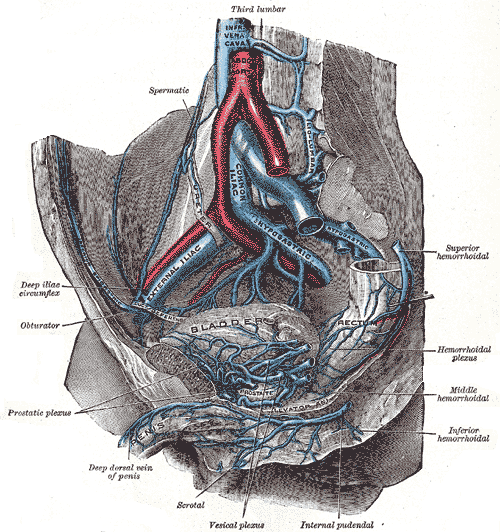

The pelvis has a vast network of arteries with several anastomotic networks, therefore, providing an extensive collateral circulation. Six main arteries enter the female pelvis to include the pair of internal iliac arteries, and ovarian arteries plus the unpaired superior rectal arteries and median sacral arteries. The male pelvis, on the other hand, only has four main arteries since the pair of testicular arteries do not go into the lesser pelvis in males.

The internal iliac artery is the main artery of the pelvis, giving blood supply to most of the pelvic viscera as well as to some of the musculoskeletal structures. Also, the internal iliac artery supplies the gluteal region, medial thigh, and perineal areas. Each internal iliac artery has a length of 4 cm. They begin as a common iliac artery and then bifurcates into the external and internal iliac arteries. This bifurcation occurs at the level of L5 and S1.

The internal iliac artery then descends posteromedially into the lesser pelvis going medial to the external iliac artery and obturator nerve. Close to the level of the greater sciatic foramen, the internal iliac then divides into an anterior and posterior trunk. The anterior division mainly supplies visceral structures like the bladder, rectum, and reproductive organs. The internal iliac artery continues down as the umbilical artery prenatally and connects to the placenta providing nutrition to the fetus. This vessel then becomes occluded at birth and becomes the fibrous cords called medial umbilical ligaments. The next branch is the obturator artery, which passes between the obturator vein and nerve.

The obturator artery gives off muscular branches, a branch to the ileum, and a pubic branch. The inferior vesical arteries in males and the vaginal arteries in females supply the inferior portion of the bladder and the pelvic urethra. Additionally, the inferior vesical artery supplies the prostate, and the vaginal artery supplies the superior part of the vagina. The uterine artery is an additional branch of the internal artery in females and supplies the uterus, uterine tubes, ovaries, and superior vagina together with the vaginal artery. The middle rectal artery, another branch of the internal iliac, supplies parts of the rectum as well as the seminal glands and prostate.

The last two branches of the internal iliac artery are the internal pudendal artery and the inferior gluteal artery. The internal pudendal artery passes through the pudendal canal, and as it exits divides into its terminal branches, the perineal artery and the dorsal artery of the penis and clitoris. The inferior gluteal artery supplies the skin and muscles of the buttocks and the posterior area of the thigh.

The posterior branch of the internal iliac artery has three branches to include the iliolumbar, lateral sacral, and superior gluteal arteries. The iliolumbar artery supplies the quadratus lumborum and psoas major. The lateral sacral arteries give off spinal branches that supply the spinal meninges. It may also give off some branches that supply the erector spinae and skin overlying the sacral area. Lastly, the superior gluteal artery supplies the muscles of the buttocks.[5]

The other main arteries of the pelvis include the ovarian artery, median sacral, and superior rectal arteries. The ovarian artery initiates from the abdominal aorta, inferior to the renal artery. In its course, it runs anterior to the ureter. As it enters the lesser pelvis and crosses the external iliac vessels, it gives off an ovarian branch and a tubal branch supplying the ovaries and uterine tubes. The median sacral artery originates from the posterior part of the abdominal aorta and gives branches to the lumbar vertebra, sacrum, and coccyx. Lastly, the superior rectal artery is a continuation of the inferior mesenteric artery and, at the level of S3 divides into two branches and supplies the superior part of the rectum and internal anal sphincter.

Venous Drainage of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The inferior vena cava is the systemic drainage, which is formed by the anastomosis of the two common iliac veins at L5. This large vessel only drains the lower rectum and anal canal from the gastrointestinal tract.

All the drainage from the abdominal viscera above the pectinate goes through the liver from the hepatic portal vein and then into the sinusoids to the liver. From the hepatic sinusoids, the venous blood drains to the hepatic veins, then into the inferior vena cava, and directly into the right atrium to be oxygenated.

The portal vein drains all the veins from the abdominal part of the gastrointestinal tube except for the lower part of the rectum and anal canal. It also drains the veins coming from the spleen, pancreas, and gall bladder. The portal vein is 8 cm. long and is formed behind the neck of the pancreas at the level of L2 by the union of superior mesenteric and splenic veins; this is the major vein that peculiarly supplies the liver with blood laden with absorbed nutrients from the alimentary canal for metabolism.[6] Its tributaries include superior mesenteric vein, splenic vein, right gastric vein, left gastric vein, cystic vein, para-umbilical vein, and superior pancreaticoduodenal vein. The portal vein tributaries anastomose with the tributaries of inferior vena cava at different sites in the body, and these sites are called portocaval anastomosis. These sites are quite relevant clinically and are at the lower end of the esophagus, the bare areas of the liver, at the umbilicus, the falciform ligament (accessory portal system of Sappey), the fissure for the ligamentum venosum, behind the peritoneum, lower end of the rectum and anal canal.[7]

The pelvic venous outflow forms by the confluence of adjoining veins in the pelvic area. The various plexuses mainly drain into the internal iliac vein with some draining into the superior rectal vein and go to the hepatic portal system. Another minor path fo venous drainage for females is the ovarian vein. The superior gluteal veins are the biggest tributaries to the internal iliac veins.

Nerves

The primary nerves in the anterolateral wall are the thoracoabdominal nerves, which originate from T7-T11 and supply the anterolateral abdominal wall muscles and overlying skin. Next, are the lateral cutaneous branches which come from T7-T9 and supplies the skin over the right and left hypochondriac regions. Then there are the subcostal nerves that come from the anterior rami of T12, which also supplies the muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall to include the most inferior portion of the external oblique muscles along with the overlying skin. Lastly, we have the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves, which are terminal branches of L1. The iliohypogastric supplies the skin overlying the upper iliac, inguinal, and hypogastric regions. The ilioinguinal supplies the lower inguinal regions, mons pubis, and anterior scrotal area.

The main innervation of the pelvis comes from the sacral and coccygeal nerves. There is also some aid coming from the autonomic nervous system. The obturator nerve forms from the anterior rami of L2-L4 and enters the pelvis. It passes through the obturator foramen, where it divides into its anterior and posterior parts. There are no pelvic structures supplied by the obturator nerve.

The lumbosacral trunk is a thick nerve that forms as the L4 unites with the anterior ramus of the L5. This trunk will then join the sacral plexus. The sacral plexus is located at the posterolateral wall of the lesser pelvis. It gives rise to two primary nerves, namely the sciatic and pudendal nerves. The sciatic nerve is the thickest of the nerves of the body and forms by the anterior rami of L4-S3. It descends and supplies the posterior aspect of the thigh and the leg and foot. The pudendal nerve is the key nerve of the perineum. It is also the chief sensory nerve of the external genitalia. The coccygeal plexus is a tiny network of nerves that come from the anterior rami of S4 and S5. It supplies part of the pelvic diaphragm. Small nerves arise from this plexus named anococcygeal nerves, which supply the small area of skin between the coccyx and anus.[8]

Surgical Considerations

The abdominal and pelvic vasculature contains a multitude of arteries and veins that are of particular note during surgical procedures. Some examples comprise but are not limited to injuries during incisions of the abdomen and pelvis, damage to the ureters during pelvic surgeries, or metastatic routes.

The inferior epigastric artery can become injured during lower abdominal wall incisions. Placement of trocars during laparoscopic procedures can also lead to injury. When these happen, abdominal wall hematomas arise and can expand to a considerable size since there is very minimal tissue resistance in that area.[13]

During Caesarean sections and hysterectomies, injury to the uterine arteries or transection can occur when there is an extension of the incision into the broad ligament. In this situation, they are also at risk of inclusion within a suture during attempts at hemostasis because of the proximity of the ureters to the uterine arteries.

Another surgical consideration is during hernia repairs, surgeons should note for a common variant of an accessory or aberrant obturator artery. This variation typically runs the same route as the pubic branch of the obturator artery and can be damaged during procedures.[14]

The lateral sacral veins anastomose with the internal vertebral venous plexus and act as an alternate route to reach the vena cava; this becomes important as a pathway for metastatic spread form prostatic or ovarian cancers to the vertebral or cranial sites.[15]

Esophageal variceal bleeding is a common complication in liver cirrhosis leading to portal hypertension. This condition results in severe hemorrhage at the portocaval anastomosis at the lower end of the esophagus.[7] The other important site of the portocaval anastomosis is the lower end of the rectum and anal canal, where pathological variation results in hemorrhoids.[16]