Definition/Introduction

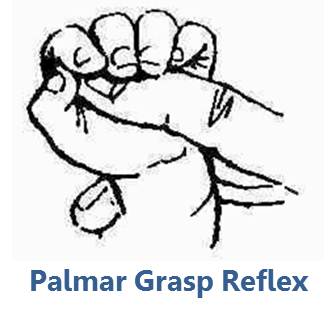

The grasp reflex is an involuntary flexion-adduction movement involving the hands and digits.[1] As the name implies, the action resembles a grasping motion of the hand. The reflex can be elicited by moving an object distally along the palm.[1][2] The movement breaks down into two phases – a catching phase and a holding phase.[1] The catching phase features the initial brief muscular contraction following stimulation of the palm, whereas the holding phase features traction of the tendons associated with the contracting muscles.[1]

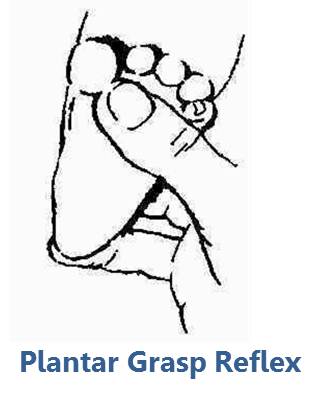

There is a similar reflex observed in the foot called the plantar grasp reflex. This reflex is observable by stimulating the medial plantar surface of the foot. When the foot grasp reflex is positive, upon such stimulation, the lateral surface of the foot will react to create an indentation in the plantar surface, resembling a cup.[2]

The grasp reflex is considered a primitive reflex, similar to the suck, snout, and palmomental reflexes.[2][3] Primitive reflexes are generally present at birth but disappear upon maturation of the nervous system as a part of normal development.[3][4]

Issues of Concern

The reoccurrence of the grasp reflex past the age of infancy is associated with focal lesions in the central nervous system (CNS) or diffuse neurodegeneration, as observed in a broad range of neurodegenerative diseases.[3] As such, the reemergence of the grasp reflex causes concern for a neuropathological process. Further, the presence of an unwanted grasp reflex may be a disabling feature of neurodegenerative diseases, contributing to decreased quality of life.[3] One of the causes of the reemergence of the grasp reflex is catatonia.

Clinical Significance

The precise neural circuit mapping of the grasp reflex has not been characterized. Research has shown that ulnar and median nerve stimulation at the wrist will yield a grasp reflex response in 40 milliseconds, suggesting that the reflex gets mediated at the spinal cord level.[5][6] Inhibition of this reflex arc ultimately comes from higher cortical brain centers in conjunction with brainstem input and becomes active as the cortex matures.[3][7] Various studies have attempted to map precisely where this inhibition comes from but have yielded inconsistent results.[3] Proposed regions involved include the cerebellar hemispheres, supplementary motor area[8], anterior cingulate gyrus, areas of the frontal lobe, and areas of the parietal lobe.[9][8][1][10]

Several conditions are associated with the reemergence of the grasp reflex in later life, including Parkinson disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, dementia with Lewy bodies frontotemporal dementia, and normal pressure hydrocephalus.[3][11] As such, eliciting a grasp reflex in an adult patient suggests an underlying neurological disease but is not a highly specific finding. The reemergence of the grasp reflex in later life is also reportedly reversible in patients with temporarily diminished cortical activity, such as drowsy or semi-comatose patients.[3][1] The shared theme across these various conditions is impairment of higher-level nervous system function, eliminating the inhibition to brainstem areas mediating the grasp reflex. In the absence of appropriate inhibition, the grasp reflex can reemerge in later life.

Although the grasp reflex may be present in a range of neurological disorders, its presence is not always pathologic. Like all primitive reflexes, the grasp reflex is normally present in infancy. The grasp reflex has been reportedly observed as early as the 16th week of gestation and is generally observable by the third trimester.[12][13] The reflex persists until between 4 and 6 months post-birth.[1] Even after infancy, the grasp reflex is rarely observable without relation to an underlying pathology. The prevalence in healthy adults aged 65 and older is estimated to be 0.1%. The prevalence in adults 65 and older with mild cognitive impairment is estimated to be 1.7%, and the prevalence in adults 65 and older with dementia is estimated to be 18.4%.[4] Thus, although it is possible to observe the grasp reflex in healthy adults, its presence is correlated with cognitive decline or some neurological pathology.[4][14]

A paucity of scholarship exists specifically looking at treating the grasp reflex in adults. Instead, research has largely focused on treating the overlying neurological disorders likely responsible for the reemergence of the grasp reflex. However, the presence of the grasp reflex can contribute to disability in patients with neurodegenerative conditions and can hinder their abilities to complete activities of daily living.[3] As such, interventions targeted at eliminating the grasp reflex could have utility.

A case study of three patients who had alcohol dependence and were already receiving treatment with benzodiazepines reported some success in eliminating the grasp reflex by treating with acamprosate.[15] The study reported that primitive reflexes, including the snout and/or grasp reflex, were eliminated within 24 hours of starting acamprosate.[15] Although this study showed promising results, we do not have data about the long-term outcomes of these patients regarding the reemergence of their primitive reflexes. Further, the sample size of 3 patients with a single disease process limits the generalizability of these study results. Nevertheless, the data from this study are suggestive of a potential pharmacological treatment for the grasp reflex and provides a starting point for future follow-up work.

Other suggested treatments involve injecting botulinum toxin into the muscles involved in the grasp reflex.[3] By preventing acetylcholine release from the presynaptic neurons at the neuromuscular junction, botulinum toxin could produce flaccid paralysis in the affected muscles that may be beneficial in cases of an unwanted grasp reflex. Although an interesting idea, this strategy has yet to be tested explicitly in the setting of relieving a grasp reflex.

Orthotics such as splints represent another suggested therapy.[3] It is possible that a carefully designed splint could oppose unwanted flexion present during the grasp reflex. This therapy has also not been subject to rigorous study also provides the opportunity for follow-up investigations.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

All health care team members need to recognize that the presence of the grasp reflex can contribute to a patient’s disability and decrease their level of independence. As such, members of the health care team should be ready to assist patients with various tasks involving the hand and dexterity that may be difficult.

As previously discussed, there have been proposals that an orthotic may play a useful role in helping patients with a grasp reflex.[3] [Level 5] Such a device represents an opportunity for an orthotist to contribute to the care of patients with a grasp reflex. An orthotist can work with the patient to create a splint or other device and evaluate its effectiveness in helping the patient.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy can greatly improve this non-physiological reflex in adults, such as in people affected by stroke.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Testing for the grasp reflex is relatively simple, involving stimulating the palmar surface of the hand in a distal direction. All members of the health care team can be trained to perform this test. As such, patients can be monitored for the presence of the grasp reflex by various healthcare team members. The new onset of a grasp reflex or a strengthened response of a preexisting grasp reflex may indicate the progression of underlying pathology. Members of the health care team should be cognizant of this finding’s significance.