Introduction

The choroid plexus is a complex network of capillaries lined by specialized cells and has various functions. One of the primary functions is to produce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) via the ependymal cells that line the ventricles of the brain. Secondly, the choroid plexus serves as a barrier in the brain separating the blood from the CSF, known as the blood-CSF barrier. In addition to these vital functions, the choroid plexus also secretes various growth factors that maintain the stem cell pool in the subventricular zone. Not only are these functions necessary for successful brain development, but they are also essential to protect against harmful microbes and toxins.

Structure and Function

CSF Production

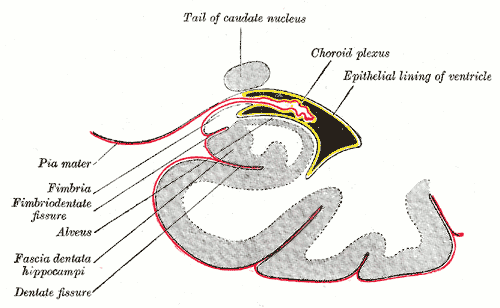

The brain is composed of three layers of meninges known as the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and the pia mater. The choroid plexus resides in the innermost layer of the meninges (pia mater) which is in close contact with the cerebral cortex and spinal cord. It is a highly organized tissue that lines all the ventricles of the brain except the frontal/occipital horn of the lateral ventricles and the cerebral aqueduct. The choroid plexus has a lining of specialized epithelial tissue known as ependyma. Ependymal cells are glial cells with a ciliated simple columnar form that line the ventricles and central canal of the spinal cord. Apical surfaces have a covering of hair-like projections known as cilia (which circulate CSF) and microvilli (which help in CSF absorption). Microvilli perform this function via their brush border, which significantly increases the surface area of the choroid plexus, permitting increased CSF absorption. Ependymal cells are essential in the production of CSF as the choroid plexus may secrete up to 500ml of CSF per day in the adult human brain.[1] Not only does CSF cushion and support the brain/spinal cord, but it acts as a filtration system to circulate nutrients and remove metabolic waste from the central nervous system. Cerebrospinal fluid flows to the third ventricle from the lateral ventricles via the right and left interventricular foramen of Monro. CSF then flows from the third to the fourth ventricle via the cerebral aqueduct of Sylvius. Lastly, CSF flows from the fourth ventricle to the subarachnoid space via the foramen of Magendie medially and via the foramen of Luschka laterally. Once CSF is in the subarachnoid space, it may be reabsorbed via arachnoid granulations and ultimately drain into the dural venous sinuses. Because CSF pressure associates with brain development, too little CSF can stunt brain growth whereas overproduction of CSF can lead to a condition known as hydrocephalus. Fortunately, excessive CSF production as a cause of hydrocephalus does not occur except in rare cases of a tumor of the choroid plexus known as choroid plexus papilloma which may cause hydrocephalus by overproduction of CSF.

Blood-CSF Barrier

The choroid plexus forms the blood-CSF barrier along with the arachnoid mater to create a pair of membranes that separate the blood from the CSF. This barrier is composed of a combination of ependymal (choroid epithelial) cells with tight junctions on its apical surface (the side facing the ventricles), and a core of fenestrated capillaries surrounded by connective tissue. Tight junctions consist of a network of claudins and proteins that serve as a checkpoint to limit the passage of substances between the cells. The blood-CSF barrier functions similarly to the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) in that it facilitates the exchange and removal of metabolites while simultaneously preventing the passage of blood-borne substances into the brain. However, the substances exchanged between each respective barrier differ significantly due to their distinct functions. For instance, the choroid plexus contains a fenestrated endothelium (BBB is non-fenestrated) which allows the rapid delivery of water to aid in CSF production. Within the choroid plexus reside microglia, white blood cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes which all serve to prevent harmful pathogens from entering, this permits normal brain homeostasis via cytokines that the choroid plexus secretes to recruit these immune cells.[2] A compromise in the blood-CSF barrier allows dangerous microbes to infect the central nervous system which is present in infections such as meningitis. In inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis, pathogenic T-lymphocytes migrate through the BBB and the blood-CSF resulting in periventricular plaques. Thus, maintenance and understanding of the mechanism of the blood-CSF barrier os a well-studied target for the delivery of novel pharmacologic agents.

Embryology

Ventricular development coincides with the development of the brain. The choroid plexus has both ectodermal and mesodermal components and begins development across the dorsal axis of the neural tube.[3] Once the neural tube closes, the choroid plexus of the fourth ventricle is the first to appear around the ninth week of gestation, followed by the simultaneous development of the choroid plexus in the lateral and third ventricles. Tropomyosin and bone morphogenetic protein are involved in the early development of the choroid plexus at these sites.[4] The tubulocisternal endoplasmic reticulum formed by the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus results in the secretion of high amounts of protein in early CSF which creates a colloid osmotic pressure that permits brain expansion. Choroid plexus cysts are the most common intraventricular cyst and are present in the antenatal period. They usually regress by week 28 of gestation and are detectable on a sonogram.[5] Some of these cysts may persist until adulthood without any clinical significance.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

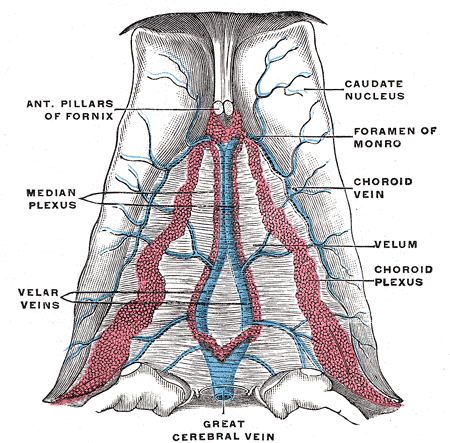

The choroid plexus receives its vascular supply from a variety of arteries due to its various locations. The anterior choroidal artery, which is the most distal branch of the internal carotid artery, supplies the choroid plexus found in the lateral ventricles. The posterior choroidal artery, which branches from the posterior cerebral artery, is known to supply the choroid plexus primarily in the third ventricle but also has a minor role in supplying the choroid plexus in the lateral ventricles. Lastly, the anterior/posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, which branch from the basilar/vertebral arteries respectively, supply the choroid plexus found in the fourth ventricle.[1]

Surgical Considerations

The choroid plexus coagulation has been accepted as one of the treatment options for infantile hydrocephalus.[6]

Clinical Significance

The choroid plexus may be involved in various pathologies that are groupable into two main categories; high volume states of CSF and low volume states of CSF.

High CSF states

High volume states of CSF are the result of either excessive production or more commonly decreased absorption by the arachnoid granulations. Choroid plexus tumors are very rare tumors which may cause excessive CSF production; these include choroid plexus papillomas and choroid plexus carcinomas. More commonly, excessive CSF state is the result of impairment of CSF reabsorption by the arachnoid granulations commonly seen in meningeal inflammatory conditions including infectious meningitis, carcinomatous meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage. All such cases result in a condition known as communicating hydrocephalus in which there is an abnormal accumulation of CSF within all the ventricular system; this results in dilatation of the ventricles and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure which include a headache, nausea, vomiting, and occasionally double vision. Hydrocephalus may also occur due to obstruction of CSF flow within the ventricular system called obstructive or non-communicating hydrocephalus. The sites of obstruction most frequently occur at the narrow cerebral aqueduct. It may also happen anywhere within the ventricular system or the outflow from the fourth ventricle into the subarachnoid space such as the foramen of Monro, the third ventricle by a colloid cyst or at the foramina of Luschka or Magendie.[7]

Low CSF states

Low volume states of CSF are most commonly due to CSF leak but may also be due to damage to the ependymal cells of the ventricles. Causes of CSF leaks include a lumbar puncture, spontaneous rupture of cystic dilatations of the arachnoid membrane lining spinal nerve roots, post-craniotomy, or severe motor vehicle accident. In such trauma-related cases, the patient may experience rhinorrhea or otorrhea of clear fluid (CSF). In states of low CSF, a patient may experience an orthostatic headache due to intracranial hypotension that is usually self-limiting unless it is due to leakage.[8] In addition to these pathological states, the ependymal cells of the choroid plexus may undergo age-related atrophy which can result in a decrease in CSF production.