Continuing Education Activity

The Babinski reflex was described by the neurologist Joseph Babinski in 1896. Since that time, it has been incorporated into the standard neurological examination. The Babinski reflex is easy to elicit without sophisticated equipment. Since it is a reflex, it does not require active patient participation and, therefore, can be performed in patients who are otherwise unable to cooperate with the neurological exam. This activity describes the technique for performing the Babinski reflex test and how to interpret the results. This activity highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with upper motor neuron lesions.

Objectives:

- Outline how to perform the Babinski reflex test.

- Describe the physiologic pathway of the Babinski reflex.

- Describe the clinical relevance of the Babinski reflex.

- Explain how the facilitation of interprofessional team education and discussion can optimize the effective performance of the Babinski reflex test and inform the need for subsequent evaluations.

Introduction

The Babinski reflex (plantar reflex) was described by the neurologist Joseph Babinski in 1896. Since that time, it has been incorporated into the standard neurological examination. The Babinski reflex is easy to elicit without sophisticated equipment. Also, it requires little active patient participation, so it can be performed in patients who are otherwise unable to cooperate with the neurological exam.[1][2][3]

Anatomy and Physiology

The Babinski reflex tests the integrity of the corticospinal tract (CST). The CST is a descending fiber tract that originates from the cerebral cortex through the brainstem and spinal cord. Fibers from the CST synapse with the alpha motor neuron in the spinal cord and help direct motor function. The CST is considered the upper motor neuron (UMN), and the alpha motor neuron is considered the lower motor neuron (LMN). Sixty percent of the CST fibers originate from the primary motor cortex, premotor areas, and supplementary motor areas. The remainder originates from primary sensory areas, the parietal cortex and the operculum. Damage anywhere along the CST can result in the presence of a Babinski sign.

Stimulation of the lateral plantar aspect of the foot (S1 dermatome) normally leads to plantar flexion of the toes (due to stimulation of the S1 myotome). The response results from nociceptive fibers in the S1 dermatome detecting the stimulation. Nociceptive input travels up the tibial and sciatic nerve to the S1 region of the spine and synapses with anterior horn cells. The motor response which leads to the plantar flexion is mediated through the S1 root and tibial nerve. The toes curl down and inward. Sometimes there is no response to stimulation. This is called a neutral response. This response does not rule out pathology.

The descending fibers of the CST normally keep the ascending sensory stimulation from spreading to other nerve roots. When there is damage to the CST, nociceptive input spreads beyond S1 anterior horn cells. This leads to the L5/L4 anterior horn cells firing, which results in the contraction of toe extensors (extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus) via the deep peroneal nerve.

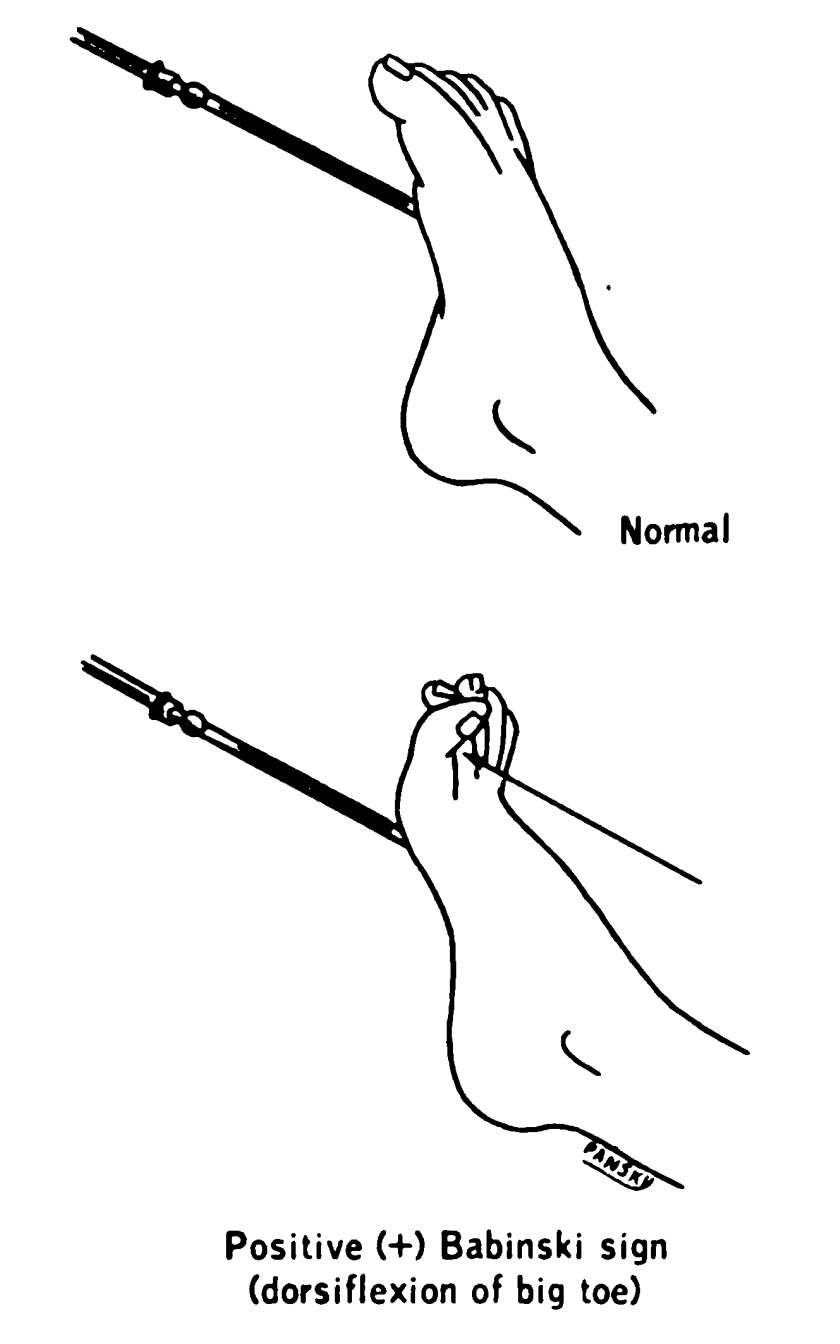

Babinski sign occurs when stimulation of the lateral plantar aspect of the foot leads to extension (dorsiflexion or upward movement) of the big toe (hallux). Also, there may be fanning of the other toes. This suggests that there is been spread of the sensory input beyond the S1 myotome to L4 and L5. An intact CST prevents such spread.

In infants with CST, which is not fully myelinated, the presence of a Babinski sign in the absence of other neurological deficits is considered normal up to 24 months of age. Babinski’s may be present when a patient is asleep.[4][5]

Indications

The Babinski reflex is done as part of the routine neurological exam and is utilized to determine the integrity of the CST. The presence of a Babinski sign suggests damage to the CST. Because the CST fiber tracts run from the brain, through the brainstem, and into the spinal cord, lesions of the central nervous system (CNS) often affect the integrity of the CST. Thus, the presence or absence of the Babinski reflex can provide very useful information on the presence or absence of pathology affecting the CNS. Babinski reflex is especially important in the setting where there is suspicion of spinal cord injury or stroke, as it may be an early indicator of the presence of these emergency conditions.[6][7][8]

Contraindications

The only contraindication to performing the Babinski reflex is a lesion (such as an infection) in the affected area of the foot that precludes the effective performance of the reflex. In such situations, one of the alternative methods of eliciting the response may be done.

Equipment

The Babinski reflex should be elicited by a dull, blunt instrument that does not cause pain or injury. Sharp objects should be avoided. The dull point of a reflex hammer, a tongue depressor, or the edge of a key is often utilized.

Preparation

The patient should be relaxed and comfortable. It is best to advise the patient that the sensation may be slightly uncomfortable. Patients may experience both a mildly unpleasant sensation as well as a tickling sensation. The examiner should ensure that the plantar surface of the foot is free of any lesions before proceeding.

Technique or Treatment

To test for the Babinski sign, the instrument is run up the lateral plantar side of the foot from the heel to the toes and across the metatarsal pads to the base of the big toe.

Many variations of the Babinski sign have been described. Each of them is designed to elicit dorsiflexion of the big toe. The more common include Chaddock (stimulating under lateral malleolus), Gordon (squeezing calf), Oppenheim (applying pressure to the medial side of the tibia), and Throckmorton (hitting the metatarsophalangeal joint of the big toe). The mechanism by which these alternatives elicit this response is likely similar to the Babinski response. These variations are useful in patients who have a significant withdrawal response to the conventional testing for the Babinski reflex.[9][2]

Clinical Significance

The examiner watches for dorsiflexion (upward movement) of the big toe and fanning of the other toes. When this occurs, then the Babinski reflex is present. If the toes deviate downward, then the reflex is absent. If there is no movement, then this is considered a neutral response and has no clinical significance.[10]

The presence of the Babinski reflex is indicative of dysfunction of the CST. Oftentimes, the presence of the reflex is the first indication of spinal cord injury after acute trauma. Care must be exercised in interpreting the results because many patients have significant withdrawal responses to plantar stimulation. When this occurs, one of the variations on eliciting a Babinski sign can be utilized.

In comatose patients, one may witness a triple flexion response. In this case, one observes flexion of the thigh, leg, and dorsiflexion of the foot. The triple flexion response represents profound dysfunction of the CST, with a spread of the reflex to the L3 and L2 myotomes. Care must be made to distinguish this from a withdrawal response. The triple flexion response is very stereotyped, whereas the withdrawal response can vary with each stimulation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Healthcare workers should be aware of other methods of elicitation of the Babinski reflex, especially in patients with an absent toe or infection of the soles. The Hoffman reflex in the upper extremity is considered the nearest equivalent of the Babinski sign. They should also be aware of potentially misleading outcomes if the procedure is performed incorrectly.[11] [Level 5]