Continuing Education Activity

External fixation has been used for the treatment of fractures for 2000 years. The application and devises have changed, but the biomechanics remain the same. This activity outlines the relevant anatomy, techniques, and fixation goals and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients who undergo external fixation.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications and contraindications of external fixation.

- Describe the equipment, biomechanics, and technique in regards to external fixation.

- Review appropriate evaluation of the potential complications and clinical significance of external fixation.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance external fixation treatment and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Physicians have been using external fixation to treat fractures for more than 2000 years after being first described by Hippocrates as a way to immobilize the fracture while preserving soft tissue integrity. The fixator design and biomechanics have changed dramatically over the years, but the principles remain the same. The primary goal of external fixation is to maintain the length, alignment, and rotation of the fracture. External fixation can serve as provisional fixation or definitive fixation purposes. Both methods can be performed in conjunction with partial internal fixation if necessary. It is important for orthopedic surgeons at a trauma center to be familiar with the techniques and principles of external fixation for various fractures of the upper extremity, lower extremity, and pelvis.

Fracture healing physiology largely depends on the mode of fixation and level of stability. With absolute fracture stability such as compression plating, the bone will undergo primary intramembranous bone healing. On the other hand, relative fracture stability, such as external fixation, results in secondary enchondral bone healing. There are also several ways to alter the external fixation construct to make the fracture more or less stable.

Influential Factors and Variables for Construct Stiffness and Stability

One method of changing the stability is to alter the pin configuration. Placing pins closer to the fracture site, adding more pins and increasing the spread of the pins will all add to the stiffness of the construct. However, one must also place the pins out of the field of future surgical approaches during definitive fixation. Any increases in pin diameter will strengthen the construct to the fourth power and reduce the stress at the bone-pin interface. Increasing pin diameter has the greatest influence on the stability of unilateral frames. That said, larger pins increase the risk of a potential stress riser and can ultimately lead to fracture.[1] For example; a 5 mm pin is 144% stiffer than a 4 mm pin.

Other variations in pin morphology include self-drilling pins, trocar tip pins, and hydroxyapatite-coated pins. Another way to change the strength of the construct is to increase the diameter of the rods or secure it closer in proximity to the bone. One can also add multiple bars to the same pins to enhance stability. Bars get secured to the pins by clamps. The most common material for bars today is carbon fiber, which is 15 % stiffer than stainless steel bars.[2]

External Fixator Types

External fixator types divide into several different subcategories, including uniplanar, multiplanar, unilateral, bilateral, and circular fixators. By adding pins in different planes (i.e., placed perpendicular to each other), one can create a multiplanar construct. Uniplanar fixation devices are fast and easy to apply but are not as sturdy as multiplanar fixation. Bilateral frames are created when the pins are on both sides of the bone and can also add additional stability. Circular fixators have gained popularity with limb lengthening procedures but are especially effective at allowing the patient to weight bear and maintain some joint motion during the treatment. They are more difficult to apply and use smaller gauge pins and more of them to distribute the weight.[3]

There are many different ways to change and enhance the external fixation construct. To complicate things further, there are also hybrid frames which are a combination of any of the previous constructs described. The surgeon must create a level of stability that is appropriate for optimal healing. It is essential also to have a good understanding of basic fracture principals because stiffer is not always better when it comes to external fixation.

Anatomy and Physiology

The relevant anatomy is dependent on the injury and type of frame applied. Circular frames, in particular, will require an in-depth understanding of the anatomy. This activity will discuss the safe zones and potential structures at risk with uniplanar pins placed in the femur, tibia, pelvis, humerus, and forearm.

In a cadaveric study by Beltran et al., it was found that the last branch of the femoral nerve crosses the anterior femur an average distance of 5.8 cm distal from the lesser trochanter and the first branch crosses the anterior femur at 2 cm. The average distance going from the proximal pole of the patella and lateral joint line to the superior reflection of the suprapatellar pouch was 4.6 cm and 9.5 cm, respectively. The joint reflection can be as high as 7.4 cm above the proximal patella, which is important to consider when avoiding penetration into the knee joint and lead to septic arthritis. The femoral artery lies directly anterior to the femoral head and traverses medially down the femoral shaft. Femoral half pins can be placed anteriorly, anterolateral or laterally. The “safe zone” while placing anterior femoral pins is a 20 cm corridor from 5.8 cm distal to the lesser trochanter and 7.4 cm proximal to the superior pole of the patella. On the other hand, lateral femoral pins can be placed anywhere on the femur and will not pose a risk to traversing neurovascular structures. The lateral pins, however, tether the fascia lata and vastus lateralis.[4]

The broad subcutaneous border of the tibia is easily palpable for safe pin placement. The recommendation is that pins be placed at least 14 mm distal to the joint line to avoid penetration into the joint.[5] Care must be taken not to protrude the far cortex to protect the neurovascular bundle. Distally, an incision and dissection down to bone may be necessary to prevent injury to the anterior tibial artery and deep peroneal nerve.[6] Moving distally along the lower extremity, the calcaneus has several nervous structures surrounding it. Specifically, the medial calcaneal nerve is at the most risk with the placement of a posteroinferior calcaneal pin. These pins are placed from medial to lateral to protect injury to the retromalleolar structures medially.

There are two main methods of external fixation of the pelvis. The iliac crest site can be easily palpated and found quickly. The clinician makes a small incision just proximal to the gluteal ridge to preserve the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Pin placement here is safe as long as the inner and outer tables of the pelvis are not penetrated. Anterior superior iliac spine pins require direct fluoroscopic visualization as the starting point and trajectory are more difficult to find.[7]

External fixation of the upper extremity is challenging, given the intimate neurovascular relationship of neurovascular structures. Proximally, half pins can be placed laterally. Care must be taken to preserve the axillary nerve and not to breach far beyond the medial cortex. The radial nerve crosses from medial to lateral around the midshaft of the posterior humerus. As a result, half pins in the middle third of the humerus get placed anteriorly. The medial and ulnar nerves run with the brachial artery and is medial to the humerus in the upper two thirds before traversing anterolaterally and posterior, respectively. Distally, the clinician can insert pins at the bony prominences of the medial and lateral epicondyles. Dissection down to the bone and the use of drill sleeves are recommended when placing pins into the humerus.[6]

The subcutaneous border of the ulna is also easily palpable, and pins can be placed ulnarly anywhere along this ridge. The ulnar nerve is at risk proximally but is easily avoidable by identifying it posterior to the medial epicondyle by palpation before it traverses anteromedially into the forearm. Radially, pins are more commonly placed into the mid-shaft or distal radius because proximal dissection of the radius will risk the posterior interosseous nerve and radial nerve. The middle third half pins in the radius get dorsally inserted. A small incision and dissection down to bone are important when placing distal radius half pins because of the risk to the superficial radial nerve.[8]

Indications

Clinicians use external fixation in orthopedic trauma, pediatric orthopedics, and plastic surgery for an array of different pathology. Below are a few of the indications for external fixation devices:

- Unstable pelvic ring injuries

- Comminuted periarticular fractures such as pilon, distal femur, tibial plateau, elbow, and distal radius fractures

- Fractures with large amounts of soft tissue swelling

- Fractures in a patient that is hemodynamically unstable or cannot undergo an open procedure

- Comminuted long bone fractures

- Fractures with significant bone loss

- Open fractures with soft tissue loss

- Limb deformity and limb lengthening

- Osteomyelitis with bone loss

- Immobilization of joint after soft tissue flap

- Arthrodesis

- Nonunion

- Malunion

- Infection

- Traction to aid in intraoperative fracture reduction

Contraindications

External fixation is a relatively safe minimally invasive procedure and can provide significant benefit to the patient when used in the correct setting. As such, there are limited contraindications for its use in orthopedics. Relative contraindications include an obese patient where safely placing pins would be difficult. A non-compliant patient is a relative contraindication because he or she may not follow up for the removal of the device. Also, peri-prosthetic fractures can limit the bone stock available to place the pins. General contraindications include patient refusal, unable to withstand the procedure physiologically.

Equipment

The following items are necessary for a standard uniplanar external fixation device using blunt pins. The size of the pin and drill will depend on the device and the bone where it will be in use.

- 15-blade scalpel

- Dissection scissors

- Soft tissue retractors

- Size-specific trocar with soft tissue protectant sleeve

- Corresponding drill bit

- T-handle wrench

- Tapping drill

- Corresponding size pins

- Bars

- Clamps

- C-arm fluoroscopy

Technique or Treatment

External fixation is used to stabilized different bones across the body, but the overall technique of application remains the same. The pin-bone interface is critical for structural integrity. The first step includes incising the skin over the pin insertion site. Care is necessary that skin and muscle are not tenting on the pin because this may lead to inflammation and pin infections.[9][10] Small Penfield-type retractors can help reflect the periosteum from the underlying bone. A trocar and drill sleeve is advanced to the bone to minimize entrapped tissue. The drill sleeve should be centered over the bone so that it traverses the near cortex, the medullary canal and exits the far cortex. Predrilling is best done with copious irrigation to prevent thermal necrosis of the bone interface. On the other hand, self-drilling pins have a drill tip point that the surgeon can place without pre-drilling. A biomechanical study by Awndrianne et al. demonstrated that self-drilling pins have 25% less purchase than non-drilling pins because the near cortex sometimes gets stripped by the resistance the screw encounters as it rotates before breaching at the far cortex.[11]

Pelvis

External fixation in the pelvis is common for both provisional and definitive fixation. The two main pin locations are the iliac wing and the anterior inferior iliac spine. For iliac wing pins, a small incision is made to bone approximately 2 cm posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine. The target insertion site is the gluteal ridge because this is the strongest and widest portion of the iliac wing. Upon breaching the cortex, the pin can be inserted manually between the inner and outer cortex. A second pin can be placed just posterior to the first pin to increase stability. Penetration through the outer table is minimized by use of a blunt tip but is tolerable because of the inherent protection of the gluteal musculature. This process can be done quickly in experienced hands and with limited fluoroscopy. Supracetabular pins are sometimes better tolerated by the patient and have better control of the pelvis than iliac wing pins.[12] However, safe placement of supracetabular pins requires fluoroscopic guidance. Supracetabular pins get placed in the dense bone from the anterior inferior iliac spine to the posterior superior iliac spine. The fluoroscopic marker of this corridor is called the "teardrop." The teardrop is about 2 cm above the acetabular dome. The obturator outlet view on intraoperative fluoroscopy is useful for identifying the teardrop. The obturator inlet view shows the pin traversing in between the inner and outer table and can show the depth of the screw. The iliac oblique view shows the depth and trajectory of the pin. The pin on this view should be directed 1 to 2 cm above the sciatic notch to protect the sciatic nerve and gluteal vessels.[7] Posterior obturator stabilization is achievable with pelvic C-clamps contacting the posterior ilium. The C-clamp can be applied quickly and without any fluoroscopic guidance. Care must be taken with concomitant sacral comminution as this can lead to over-compression and sacral nerve injury.

Upper Extremity

The forearm may require stabilization for comminuted both bone forearm fractures with large soft tissue defects, and achieving stabilization is best with 3 or 4 mm screws in the ulna given the subcutaneous location. The superficial radial nerve and the posterior interosseous nerve is at risk during pin insertion into the radius and should be avoided. However, distal radius fractures are best stabilized with the distal pin in the base of the second metacarpal bone and the proximal pin on the radius just posterior to the radial artery. Both pins will require a small incision and blunt dissection to avoid injuring the superficial radial nerve.[6]

Humeral fractures rarely require external fixation for stabilization but are sometimes used with a morbidly obese patient or when there is gross contamination or open wounds. Pins are placed anterolaterally in the proximal humerus and posterolaterally in the distal humerus. Care must be taken to not avoid the axillary and radial nerves proximally and olecranon fossa distally. Floating and unstable elbows get stabilized with the proximal subcutaneous ulna and posterolateral distal humerus pins.

Lower Extremity

Pin placement for femur stabilization can be directly lateral or anterolaterally. Care must be taken to avoid joint penetration. Likewise, these same anterolateral distal femur pins can be used to in conjunction with subcutaneous anteromedial tibial pins placed at least 14mm distal to the joint line. The knee should be secured at 5 to 15 degrees of flexion. Moving distally, pins can be placed along the anteromedial surface of the tibia to stabilize the tibia further. Care must be taken to avoid the anteriorly traversing neurovascular structures when placing pins distally on the tibia.[5]

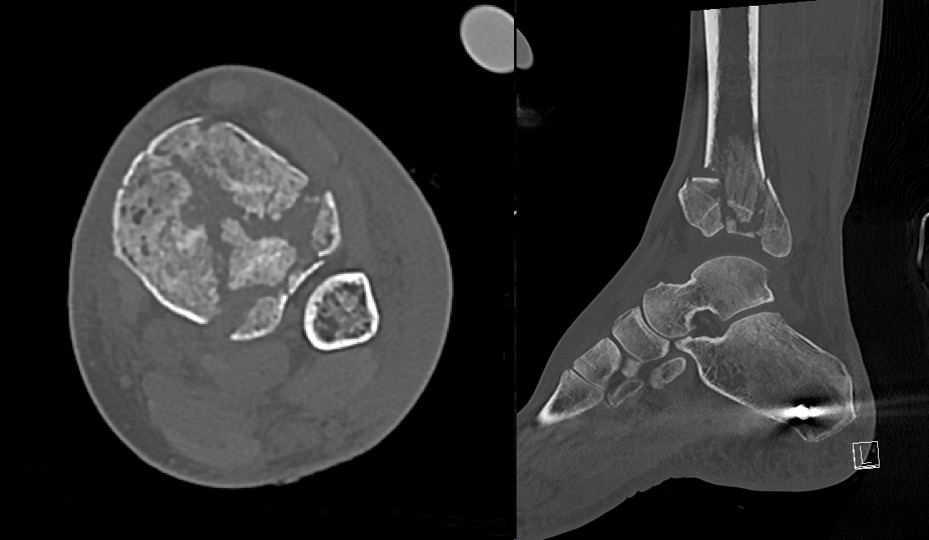

Pilon fractures commonly require temporary external fixation while soft tissue swelling subsides. The common construct to stabilize these fractures is the delta frame. It consists of a transfixation calcaneal pin and an anteromedial tibial shaft pin. Extra pins can be placed in the first metatarsal or adjacent to the transcalcaneal pin to reduce rotation about the ankle and increase the stability of the delta frame. A retrospective study by Shaw et al. demonstrated that uniplanar external fixation around the ankle could be safely applied in the emergency department without any increase in postsurgical complications.[13]

Pin Site Care

Pin site care is essential to reduce infection rates but the technique of which varies considerably. There are several different methods, and there have not been conclusive data to support that one approach is superior to another. A 2015 systematic review concluded that there remains no literature consensus regarding the potential implementation of a universal protocol that can reliably and reproducably eradicate the risk of pin site infection.[14]

Postoperatively, the pins are sometimes wrapped with xeroform or iodine impregnated gauze. Motion around the skin-pin junction is known to increase the risk of infection. Compressive garments under the external fixator bars can help reduce the motion while the skin is healing around the pins. Camathias et al. looked at how daily pin care vs. no pin care regarding pin care stability and soft tissue integrity. The study found that there was no difference between the two groups and suggested that routine pin-tract care is unnecessary as long as the patient performs daily hygiene in the shower.[15] If skin drainage or erythema surrounds the pins, then providing pin care three times a day should commence until the infection clears.

Complications

The following list includes complications that can occur with external fixation treatment:

- Pin site infection

- Osteomyelitis

- Frame or pin/wire failure or loosening

- Malunion

- Non-union

- Soft-tissue impalement

- Neurovascular injury

- Compartment syndrome

- Refracture around pin

Clinical Significance

External fixation plays a vital role in fracture care today. Not only can it temporarily stabilize fractures, but it can provide definitive fixation as well. The use of external fixation in a damage control setting can prevent the so-called “second hit” phenomenon because of the quick application, decreased blood loss, and minimally invasive application. Furthermore, by giving time for the soft tissues swelling to subside in severe injuries, the risk of injection and wound complication proportionally decreases.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach is crucial for maximizing treatment benefits and reducing morbidity. These patients are often polytrauma patients and require management in the intensive care unit. Coordination with the primary trauma team is paramount to plan interval surgeries. Daily assessments by the orthopedic and orthopedic specialty-trained nursing teams are essential for monitoring pin site infections, soft tissue integrity, and neurovascular status. Nursing also provides post-procedure monitoring, wound dressing, medication administration, and should report any issues to the treating clinician. Subsequently, consultation with physical therapy and occupational therapy are crucial to help the patient mobilize while the external fixation device is in place, and they should keep the healthcare team apprised of progress or relapses should they occur. Thus, the interprofessional healthcare team approach is the optimal means to drive positive patient outcomes with external fixation. [Level 5]