Continuing Education Activity

Anthrax is a spore-forming rod that is readily found in soil in tropical environments. Anthrax has many features that make it an optimal biologic weapon. It is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates and only a small dose is required for infection to occur. There is no rapidly available diagnostic test for anthrax infection and no universally available effective preventive vaccine. The pathogen is widely available and the production of a biologic weapon is feasible. In recent history, anthrax has been used as an agent of biologic warfare in both the United States and abroad. This activity examines when anthrax infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis and how an interprofessional team should properly evaluate for it.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of anthrax.

- Outline the presentation of a patient with anthrax.

- Identify the treatment and management options available for anthrax.

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving care and outcomes in patients with anthrax.

Introduction

Anthrax is a spore-forming rod that is readily found in soil in tropical environments. Anthrax has many desired features that make it an optimal biologic weapon because it has the following features including high morbidity and mortality rates, low infective dose, lack of rapid available diagnostic tests, lack of universally available effective vaccine, potential to cause anxiety and fear, wide availability of pathogen, feasibility of production, environmental stability, and potential to be weaponized. In recent history, anthrax has been used as an agent of biologic warfare in both the United States and abroad. In 1979, an accidental release of anthrax spores from a Soviet Union bioweapons facility in Sverdlovsk, Russia infected 77 people with diagnostic certainty.[1] Of those infected 66 died within 1 to 4 days following the onset of symptoms. In September 2001, a government employee of the US Army Research Institute for Infectious Disease intentionally distributed anthrax spores through the US Postal Service.[1] Eleven people who came in contact with the infected mail were later diagnosed with inhalational anthrax, and 5 died from their illnesses. Eleven additional patients were diagnosed with cutaneous anthrax, all of whom survived.

Etiology

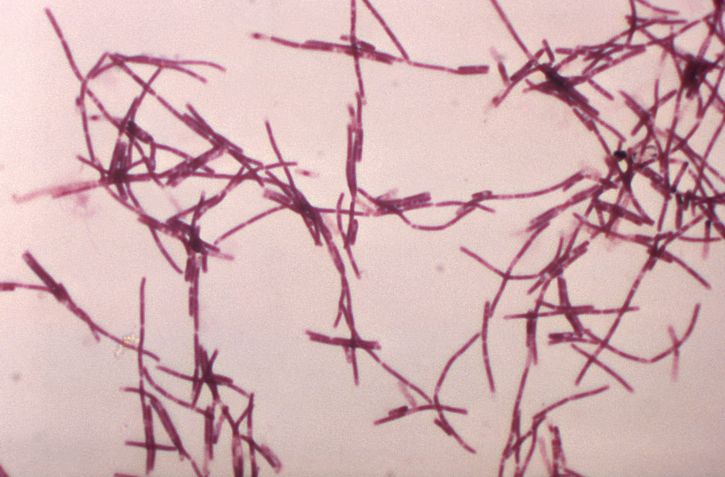

The bacterium Bacillus anthracis is a nonhemolytic, non-motile, gram-positive spore-forming rod[2][3]. It is classified as a facultative anaerobe. Virulence of the organism depends on acquiring 2 plasmids, 1 carries the gene for the protein capsule while the other carries the gene for its exotoxin. The exotoxin consists of three proteins a protective antigen, edema factor, and lethal factor[2]. Illness from anthrax is caused by its spores that germinate into bacilli inside macrophages of an infected host. Once within the host organism, the bacilli begin to produce disease by releasing toxins such as protective antigen, edema factor, and lethal factor that cause cell death, lymphadenopathy, and edema.

Epidemiology

Populations at risk for infection from anthrax are those who ingest under-cooked meat contaminated with spores, and those living in rural and agricultural areas. Exposure to livestock, infected meat, and infected soil increase risk for the development of the disease. Occupations such as veterinarians, farmers, wool sorters are at higher risk.

Human-to-human transmission has not been reported, and researchers do not believe it occurs. The organism is found within the environment with herbivores like sheep, cattle, and goats the most commonly infected after they consume spores in contaminated soil where they can survive for years. Anthrax is rarely seen in developed countries due to animal and human vaccination programs. It is reported that cases of anthrax infections are 95% cutaneous, 5% respiratory, and 1% gastrointestinal. However, the low reported incidence of gastrointestinal anthrax may be secondary to the fact that it most commonly occurs in under-served areas with poor access to healthcare and diagnostic testing, and that symptoms can vary immensely in clinical presentation. Mild and self-limiting symptoms may be under-reported. This may all lead to poor identification of the causative organism and the ultimate failure to diagnose gastrointestinal anthrax.

Pathophysiology

There are 3 types of anthrax infections which include inhalational, GI, and cutaneous. The 3 forms of the disease emerge based on the organism’s mode of entry into the host. In GI anthrax, the spore is consumed, and symptoms emerge after 1 to 6 days of incubation. Anthrax then adheres to the gastrointestinal epithelium where it germinates and creates superficial ulcerations visible on endoscopic examination. This differs from hematogenously disseminated inhalation anthrax where the ulcerations begin submucosally. However, vegetative cells can migrate into the bloodstream from these superficial ulcerations where they can rapidly multiply creating septicemia and progression to severe symptoms. In a minority of patients, they may be entirely asymptomatic. While others may develop fulminant upper and lower GI bleeding, septicemia, and death. Survival provides patients with some natural immunity. In the United States, GI anthrax has not been reported. However, there are 1 to 2 cases annually of cutaneous anthrax.

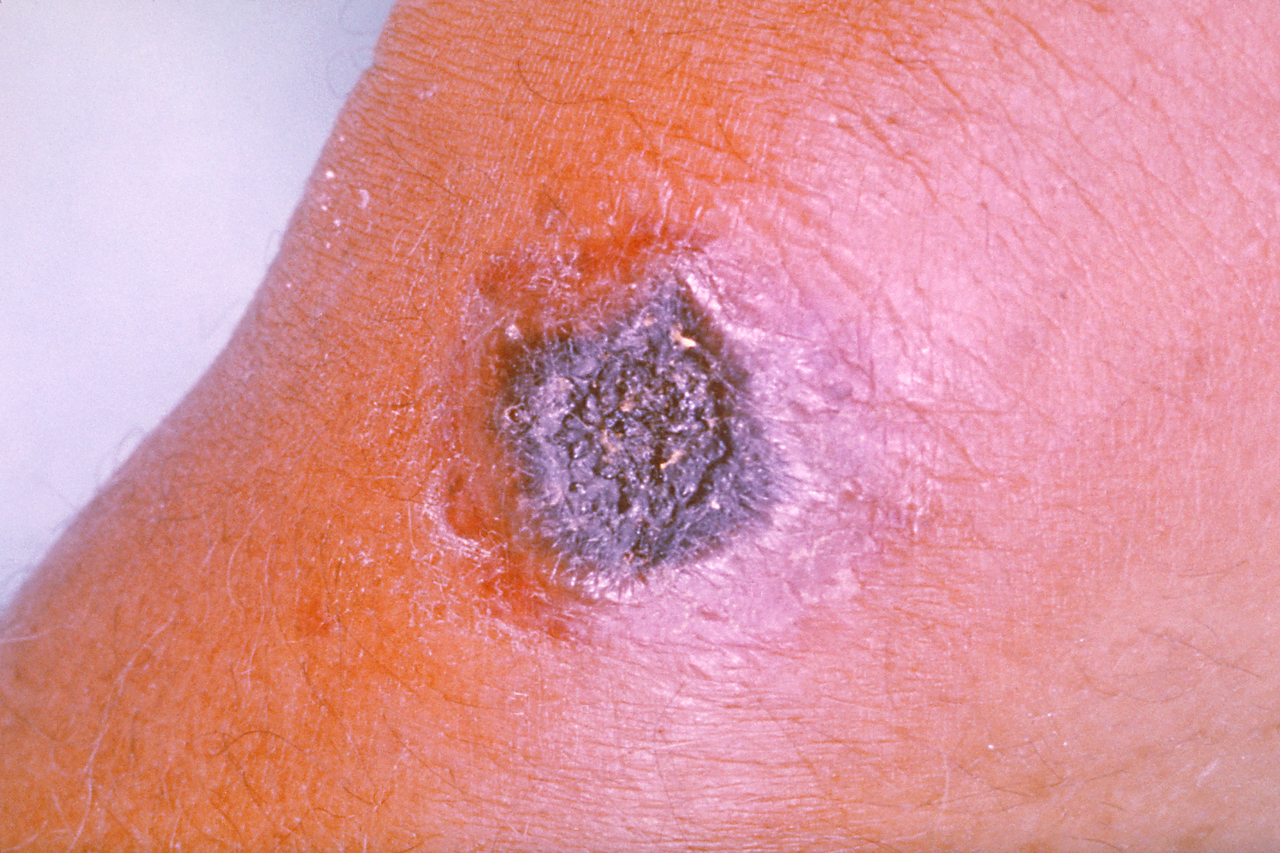

Similarly, cutaneous anthrax has an incubation period of 1 to 5 days. Clinically, it appears as a papule that progresses to form a large vesicle. The lesion becomes edematous secondary to the release of the exotoxin, and the patient develops associated regional lymphadenitis. Roughly a week later, the lesions rupture, and an eschar develops. While impressive in appearance, the skin lesions are described as non-tender and painless. Over the next couple of weeks, the eschar sloughs off and the patient either has a resolution of illness or develops signs of disseminated disease. If this occurs, untreated mortality is less than 20%. However, treatment with antibiotics decreases the risk of dissemination and death.

Inhalation anthrax is the most lethal of the three types of exposures. Once inhaled the organism is phagocytized by macrophages, the spores germinate within the tracheobronchial lymph nodes and multiply. During an incubation period of 2 to 10 days, the patient develops influenza-like symptoms with malaise, fever, and nonproductive cough. It is important to note that the presentation can be delayed for more than 1 month. Patients can also demonstrate abrupt deterioration and develop shock, hemorrhagic mediastinitis, and airway compromise. Death usually results within 72 hours after symptoms start with an estimated mortality of 50%.

Toxicokinetics

Virulence of the organism depends on acquiring 2 plasmids, 1 carries the gene for the protein capsule while the other carries the gene for its exotoxin. The exotoxin consists of three proteins a protective antigen, edema factor, and lethal factor. Infection is also dependent on the mechanism of exposure and the number of spores. It is estimated that roughly 10,000 spores are required for significant disease. However, after the 1979 Sverdlovsk incident and the intentional distribution of anthrax in the US mail in 2001, these numbers have been called into question. It is believed that the number of spores needed to cause disease may be far less.

History and Physical

The typical history will include a patient living in an endemic tropical environment or a rural or agriculture area.[4] The patient may have had exposure to grazing herbivores, animal hides, or work near these animals.[5] Exposure may also include a laboratory worker in contact with infectious spores or someone who has come in contact with white power, contaminated needle,[6][7], or wound exposed to soil from an endemic tropical area. These populations may develop inhalation, oropharyngeal, GI, or cutaneous symptoms based on the mode of entry into the host. Therefore, symptoms vary vastly, and a high level of suspicion is required.

The development of a non-painful eschar in these high-risk populations should also prompt immediate consideration for the infection. They may develop lesions with significant edema within the oropharyngeal cavity necessitating prompt airway evaluation and management. Similarly, unexplained ascites, peritonitis, or frank GI hemorrhage should be considered as possible presentations of anthrax infection. Respiratory symptoms may be vague initially with the presentation appearing similar to flu-like symptoms with fevers, malaise, and nonproductive cough. However, in all modes of infection, symptoms can progress rapidly to florid sepsis, shock, and cardiopulmonary collapse. Therefore, a high index of suspicion should guide history to elucidate possible risks for exposure.

Injectional anthrax was previously reported in a number of patients, with substance abuse, manifesting in the form of extensive soft tissue edema and necrosis. It was inferred that the subcutaneous injection(heroin, etc) provided a site for the germination of spores. Injectional anthrax was associated with a higher risk of septic shock and mortality compared to cutaneous anthrax.[8]

Evaluation

In cutaneous anthrax, the diagnosis is mostly clinical. However, confirmation can be established by the culture of the lesion, serologic testing, or punch biopsy. Anthrax can be cultured on nutrient agar or blood agar.[9]

In inhalation anthrax, typical radiographic findings are not obvious however a widened mediastinum with hilar adenopathy has been described. CT scanning of the chest is more sensitive and is recommended if inhalational anthrax is suspected. Sputum culture, gram stain, and blood cultures should be obtained in suspected cases of anthrax. However, these tests are not helpful in the acute phase of the illness. Identification of anthrax markers in the pleural fluid by PCR, serologic detection of immunoglobulin to protective antigen, and immunohistochemical testing of biopsy specimens are also available to aid in diagnosis.

Similarly, the gastrointestinal variant of anthrax can be identified by its DNA using PCR assay, blood cultures, and analysis of the ascitic fluid. PCR and cultures should also be run on stool samples or rectal swabs to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Traditional management includes supportive care and penicillin. However, with growing concerns for the weaponization of anthrax and likely resistance to penicillin, the CDC recommends broader coverage with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline. These recommendations include coverage in all patients affected, regardless of age, given the consequences of incomplete treatment which can carry more than a 50% mortality. Well-appearing patients diagnosed with cutaneous anthrax can be treated as an outpatient with ciprofloxacin or doxycycline for 7 to 10 days. All other patients should be treated with intravenous (IV) ciprofloxacin 400 mg every 12 hours or doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours plus at least 2two other antibiotics (e.g., imipenem, clindamycin, rifampin, or an aminoglycoside). Treatment must continue for at least 60 days or until 3 doses of the anthrax vaccine can be given. The recommended administration of the vaccine is on days 0, 14, and 28. All other interventions including chest tube placement and mechanical ventilation have not been shown to improve survival.

In cases of suspected exposure to anthrax, postexposure prophylaxis is recommended.[10] Choices for post-exposure antibiotics include ciprofloxacin 500 mg or doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for a total of 60 days or until patients have received at least 3 doses of the vaccine. It is important to note that the FDA has approved the vaccine for adults but not in children.

Differential Diagnosis

- Cutaneous: Bubonic plague, lymphocutaneous tularemia, cat scratch disease, brown recluse spider bite, primary syphilis, abscess, erythematous granuloma annulare

- Respiratory: Influenza, pneumonia, pneumonic plague, hemopneumothorax, pneumothorax, PE, ACS, AAA, PUD

- GI: PUD, Boerhaave syndrome, peritonitis, perforated viscus, shigella, amebic dysentery, ulceroglandular tularemia, bubonic plague

Prognosis

While the actual mortality of inhalational anthrax is unknown, mortality is believed to be 50% or higher after disease onset. Untreated gastrointestinal anthrax also carries a mortality rate of 50%, but with appropriate treatment mortality rates decrease to less than 40%. Of all forms, cutaneous anthrax carries the best prognosis with a mortality estimated to be below 20%.

Complications

- Hemorrhagic mediastinitis

- Fulminant GI bleeding

- Meningitis

- Septic shock

Pearls and Other Issues

When caring for a patient who may have been infected with anthrax, standard universal precautions should be utilized as well as decontamination to avoid exposure to healthcare workers and others. Currently, human-to-human spread is not believed to occur. However, with the believed low inoculation dose and potential for high mortality, all efforts need to be taken to avoid further exposures. It is important to remember that this agent has a high risk of weaponization with potential resistance to standard therapy. Therefore, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated as soon as the infection is suspected and before confirmation of the condition.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

To defend humanity against the use of such biologic weapons like anthrax ongoing research, surveillance, and awareness of the potential dangers are required. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies anthrax as a potential category A agent, which includes the highest priority pathogens that pose the greatest threat to national security. Therefore, recognizing signs and symptoms of this pathogen, understanding its progression, and containing a possible threat are strategies that need to be mastered by a coordinated interprofessional team of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and government monitoring systems.