Continuing Education Activity

Myocardial infarction occurs when blood flow to a part of the heart diminishes or stops altogether, causing irreversible damage to the heart muscles. Acute myocardial infarction involving only the right ventricle is a much less common condition than left ventricular infarction. However, this is becoming a more commonly detected entity as the diagnosis and options for treatment evolve. This activity illustrates the evaluation and management of right ventricular myocardial infarction and explains the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the cause of right ventricular myocardial infarction.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with right ventricular myocardial infarction.

- Summarize the treatment options for right ventricular myocardial infarction.

- Outline the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to improve the hemodynamics, provide ionotropic support and reduce pulmonary vascular resistance which will improve outcomes for patients affected by right ventricular myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Infarction of the right ventricle with or without left ventricular involvement is becoming a more commonly diagnosed entity as the tools for diagnosis and options for treatment evolves. This activity will discuss the pertinent topics related to the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of right ventricular myocardial infarction (RVMI).[1][2][3][4] RVMI was first identified in patients with inferior wall MI who had elevated right ventricular (RV) filling pressures and RV failure, with normal values for the left ventricle (LV). RVMI can occur with or without LV involvement. When inferior MI is associated with RVMI, patients show more bradycardia, need for pacing, hypotension, and mortality.

Etiology

The right ventricle is less susceptible to infarction than the left ventricle. This is because it is a thin-walled structure with low demand for oxygen and lower pressures. Despite these differences, RVMI is most often caused by atherosclerotic disease.

Epidemiology

The incidence of right ventricular myocardial infarction coexisting with inferior wall left ventricular dysfunction ranges from 10 to 50%. This wide range is due to the difficulty in identifying the condition in living patients. Autopsy results show a higher rate. Cases of isolated right ventricular infarction or dysfunction are rare, except for iatrogenic causes during procedures involving the heart (i.e., interventional procedures or cardiac surgery). Another confounding variable is the fact that RV stunning can be temporary, make detection even less likely.

Pathophysiology

The right ventricle (RV) receives its arterial blood supply primarily from the right coronary artery (RCA), which arises from the right coronary cusp of the aorta. The division produces the conus artery, which supplies blood flow to the right ventricular outflow tract. The RCA from the second division also supplies the sinoatrial node (SA). Coursing in the atrioventricular groove, the RCA then gives off multiple, small branches to supply the anterior RV before dividing terminally into the acute marginal branch (AM) that runs anteriorly along the diaphragm and the posterior descending artery (PDA) that runs posteriorly. The PDA also supplies the atrioventricular node (AV) in 90% of patients, with a branch of the left circumflex artery providing flow in the remainder of patients. The PDA supplies the inferior wall of both ventricles and is a terminal branch of the RCA in 85% of patients but may arise from the left coronary circulation in 15% of the population.

The primary effects of RV ischemia and infarction result from decreased RV contractility. This leads to a reduction in blood flow from the venous system to the lungs and finally to the left side of the heart. The clinical signs of this are increased right-sided heart pressures, increased pulmonary artery (PA) systolic pressures, and decreased left ventricular preload. Symptoms may include peripheral edema, especially distention of the jugular vein, hypoxemia, and hypotension.

Additionally, as the RV dilates, the motion and function of the interventricular septum are altered. If the RV is dilated secondary to overload or if the septal myocardium is jeopardized by simultaneous left ventricle (LV) ischemia, the symptoms of hypotension and cardiac failure may be pronounced. If the septum shifts leftward during diastole, it impedes left ventricular filling, and as a result, cardiac output is decreased. This is termed loss of biventricular interdependence.

History and Physical

Patients with RV infarction may present with symptoms commonly seen in left side infarction, including chest pain with or without radiation, dyspnea, nausea, and dizziness. There can be rhythm abnormalities ranging from bradycardia to complete heart block. Hypotension may also be more common in this population. Other signs of right heart failure, such as acute peripheral edema and jugular venous distention, also can occur. The triad of jugular vein distention, clear lung fields, and hypotension is the classic picture of right ventricular dysfunction. A pan-systolic murmur best heard at the left lower sternal border may indicate tricuspid regurgitation, but due to the lower filling pressures of the right heart, this is not always present. Rarely, third and/or fourth heart sounds generated by the RV are heard at the left lower sternal border. These increase with inspiration.

More than 30% of patients with inferior wall MI also have RV involvement, but only 10% have significant hemodynamic effects attributable to RV dysfunction.[5][6]

Marked sensitivity to preload-reducing agents, including nitrates, morphine, or diuretics, is a clue to the presence of hemodynamically significant right ventricular dysfunction.[7]

Evaluation

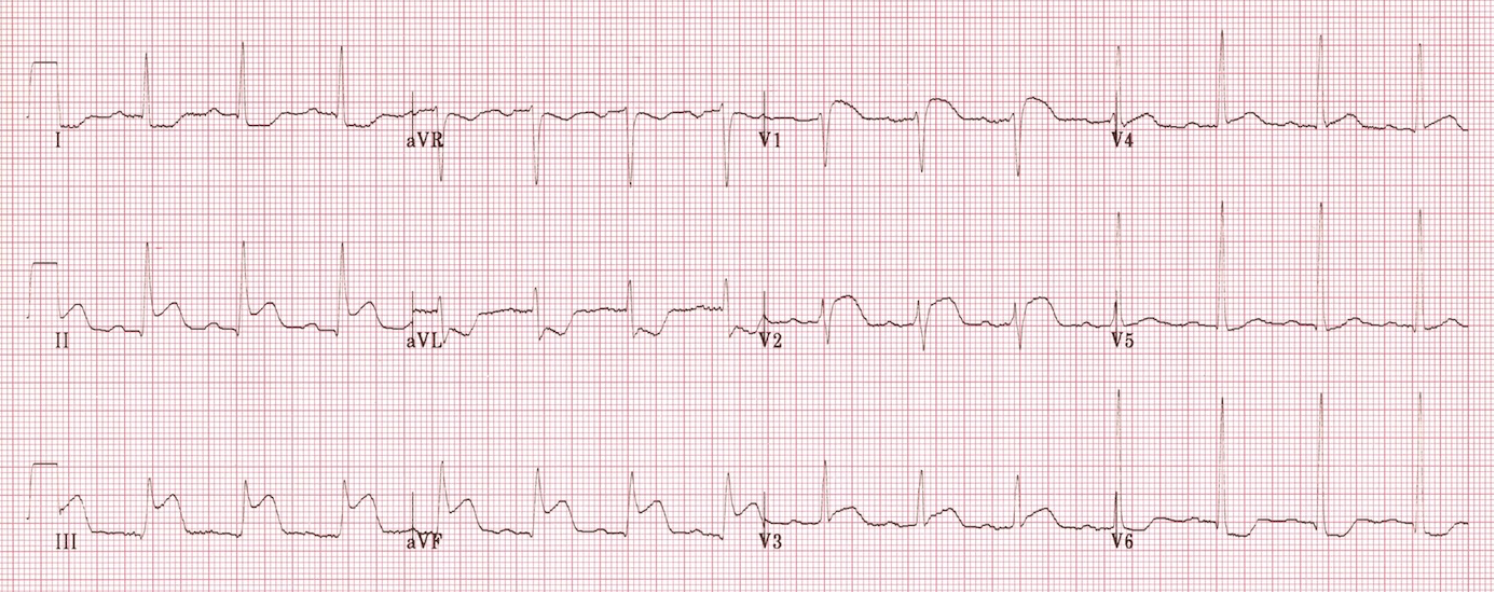

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is the first diagnostic test performed in patients complaining of chest pain. If the left ventricle is involved, evidence of inferior lead ischemia/infarction in leads II, III, and AVF is likely to be present. Disproportionate ST-elevation in lead III>II is pathognomonic for RVMI and warrants further investigation. ST elevation in the V1 lead is also highly suspicious for RVMI and is even more specific when coupled with ST-depression in lead V2. Overall, conventional left-sided electrocardiography is a poor indicator of RV ischemia/infarction due to the position of the right side of the heart. If right side dysfunction is suspected, a right-sided ECG is the most sensitive and specific, as ST elevation in V4R >1.0 mm has 100% sensitivity, 87% specificity, and 92% predictive accuracy. Conduction abnormalities such as right bundle branch block, bradycardia, or complete heart block can also manifest themselves in the ECG but may also be non-specific.[8][9][10][11]

Cardiac enzymes will be elevated in RVMI, similarly to LVMI scenarios. However, when differentiating between hemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism (PE) and RVMI, the picture is not as clear, as both troponin-I and CK-MB levels may be elevated in a minority of cases of significant PE.

Echocardiography has a high threshold for detecting right-sided myocardial dysfunction, and its increasing availability and fidelity has made it a rising diagnostic modality in a variety of settings such as the emergency department and the operating room. The sensitivity and specificity of echocardiography may be as high as 82% and 93%, respectively, for detection of right ventricular infarction. Signs include right ventricular wall dyskinesia/hypokinesia, paradoxical septal motion, tricuspid regurgitation, and pulmonary regurgitation. Other measurements such as tricuspid annular plane excursion (TAPSI) are currently being evaluated and may indicate a poor prognosis.

Myocardial performance index (MPI) is the sum of the isovolumic relaxation and contraction time divided by the ejection fraction. MPI of 0.30 or greater suggests the presence of a right ventricular infarction.[12]

Coronary angiography and ventricular scintigraphy are the gold standards for definitive diagnosis. These procedures are invasive, require a large use of resources, and are often performed during intervention; their place in the initial evaluation and workup is limited. Chest radiography also has limited specificity and diagnostic capability. Findings of an enlarged heart silhouette, dilation of the inferior or superior venae cavae, and clear lung fields may be present. The presence or absence of pulmonary edema may be useful in determining the presence or extent of concomitant left ventricular dysfunction or further evaluating for the presence of a pulmonary embolus (PE).

Hemodynamic monitoring shows a disproportionate elevation of right atrial and ventricular filling pressures compared to left-sided hemodynamics and the pulmonary artery. In addition, there may be a prominent y descent of right atrial pressure, an exaggeration of the normal inspiratory decline in pressure in the systemic arteries, and an increase in right atrial pressure with inspiration. These findings can be confused with constrictive or restrictive pathology.

Treatment / Management

Decreased right heart function, if clinically significant, may lead to decreased left ventricular preload, decreased cardiac output, and eventually systemic hypotension. One approach to the treatment of suspected RVMI includes administering a fluid challenge of 500 milliliters of crystalloid fluid. It is important to monitor for improvement in hemodynamics, or lack thereof, as patients may present with variable volume statuses ranging from hypovolemia to fluid overload. Treatment with nitrates may be harmful, as the ventilation and drop in preload can worsen RV dysfunction and systemic flow.[13][14][15]

Pharmacologic therapy with inotropic agents may be warranted if the fluid response is suboptimal. The most studied agent is dobutamine. It has been shown to improve cardiac index and RV stroke volume. Additionally, dobutamine improves left ventricular function, further promoting forward flow. The combination of inhaled nitric oxide combined with dobutamine also has the added benefit of reducing pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), thereby decreasing RV afterload and myocardial work. Milrinone, a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor, may also improve RV dysfunction. The increased cAMP levels from milrinone administration led to increased RV contractility and decreased PVR. However, milrinone is not a selective pulmonary vasodilator, and its use must be weighed against the risk of exacerbating systemic hypotension. A class of agents known as calcium sensitizers may also improve RV function, but their use is limited to European centers at this time. One such agent, levosimendan, has been shown to improve RV function. The mechanism of action involves improving cardiac contractility by increasing cardiac myocyte sensitivity to intracellular calcium without increasing calcium concentrations. The clinical effects of this drug are increased inotropy, as well as peripheral vasodilation.

Patients with LV dysfunction as well may need afterload reduction with nitroprusside or an intra-aortic balloon pump. Avoid diuretics and vasodilators if possible.

Due to the location of the conduction system of the heart, arrhythmias ranging from bradycardia to complete heart block may arise in patients with RVMI. The decreased preload and relatively fixed LV stroke volume mean that systemic cardiac output is somewhat rate-dependent. Additionally, it has been shown that AV pacing in patients presenting with RVMI and complete heart block can improve survival, while ventricular pacing alone does not.

Similar to the treatment of LV infarction, time of revascularization is the primary factor dictating survival and recovery. Earlier intervention is favored in either instance. It is the only treatment modality targeted at treating the cause of RVMI, while the other treatment options mentioned here are for symptomatic management of the sequelae. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention is the best option, but thrombolytic therapy is an option. Improved in-hospital mortality rates at 30 days were significantly improved, especially in patients with The use of ventricular assist devices (VADs), both surgical and percutaneous, have been shown to improve survival. Still, data is limited primarily to case reports and small studies. An intra-aortic balloon pump is also a treatment option. In addition to augmenting left heart function, the elevation of diastolic flow and coronary perfusion may help improve blood flow to the right heart distribution.

Short term prognosis of patients presenting with RVMI is worse than those with isolated LVMI. Both in-hospital morbidity and mortality are increased. This is likely due to the critical complications that can occur from significant RV infarction, which may require additional invasive procedures and manipulation (i.e. placement of ICDs, placement of VADs, arrhythmias). The long-term prognosis of patients who are discharged from the hospital after treatment and resolution of RVMI is similar to that of patients with LVMI.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute mitral regurgitation

Prognosis

The prognosis is based on several factors. Inferior wall myocardial infarctions complicated by RVMI have a worse prognosis than either alone. If patients have do not have RV failure, the in-hospital 30-day mortality rate was 4.4% with thrombolytic therapy and 3.2% with PCI. This increases to 13% for thrombolysis and 8.3% for PCI in patients with RV failure. In patients with cardiogenic shock, mortality increases to 100% with thrombolysis and 44% with PCI.[16]

Pearls and Other Issues

Diagnosis of RVMI, especially in the absence of acute hemodynamic changes or shock, requires a high threshold of suspicion. Findings from the initial evaluation of patients presenting with chest pain may not clearly show the evolving ischemia in the right heart. The possibility of other etiologies such as pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, and causes of hypovolemia may cloud the clinical picture. When possible, the employment of non-invasive diagnostic modalities such as echocardiography may help detect problems sooner than traditional tests of myocardial ischemia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of right ventricular infarction are complex and require an interprofessional team that includes a cardiologist, internist, nurse practitioner, radiologist, and intensivist. Most of these patients have risk factors for coronary artery disease, and healthcare workers must emphasize weight control, discontinuing smoking, regular exercise, medication compliance, and lowering blood cholesterol. The short-term prognosis for treated patients is good, but over the long term, the condition carries high morbidity and mortality.[17][18] [Level 5]