Continuing Education Activity

Ocular burns can be a true ophthalmic emergency. Prompt assessment and intervention are necessary to minimize the amount of tissue damage that occurs in the minutes to hours after the injury. After the initial insult has been appropriately managed, care must be taken to ensure appropriate specialist follow-up. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of ocular burns and highlights the interprofessional team's role in managing the potential complications from ocular burns.

Objectives:

- Review the types of ocular burns.

- Describe the initial management of ocular burns.

- Review the role of therapeutics in the management of an acute ocular burn.

- Explain how to optimize patient outcomes through appropriate care coordination and communication between acute care providers and ophthalmology.

Introduction

Acute ocular burns may constitute an ophthalmic emergency. The severity of the injury depends on multiple factors. These factors include the offending agent, length of exposure, the surface area affected, and which ocular tissues are involved. Moderate to severe burns of the eye and the ocular adnexa cause serious morbidity and may result in long-term consequences on both vision and quality of life. Acute and chronic pain, scarring with resulting disfigurement, loss of normal function of the protective adnexa, and permanent vision loss are common sequelae of more severe burns.[1] Permanent loss of vision is associated with an elevated risk of future injuries, depression, chronic disease, and other serious biopsychosocial issues.[2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Burns of the eye and ocular adnexa can be divided into two general categories, thermal and chemical. There are important distinctions between these two categories in how the injury progresses immediately after the injury. Tissue damage from thermal burns quickly abates once the heat energy is no longer in contact with the patient or after the source loses its thermal energy. Common examples of these mechanisms include patients removing themselves from a house fire and a flash burn from an explosion or fireworks injury. Due to the blink reflex and the protective nature of the ocular adnexa, the skin of the eyelids may receive most of the damage from thermal injuries. Direct thermal burns to the ocular surface typically cause superficial injury due to brief contact time. Common causes of thermal ocular burns include hot water, hot cooking oil, curling irons, and a flame, as seen in an explosion or a fire. These thermal burns can be expectantly managed like other superficial corneal injuries.[6]

Chemical burns to the eye require more aggressive initial management. The tissue damage may persist and extend deeper into the ocular structures as long as the chemical remains in contact with the eye and ocular adnexa. Therefore, chemical ocular burns require intervention to remove the insult and prevent ongoing damage to the ocular surface and deeper structures. Chemical burns may occur from exposure to everyday household items such as drain or oven cleaner, laundry or dish detergent, bleach, and ammonia. Injuries also occur with industrial exposures to substances such as fertilizers, industrial acids, lye, lime, and cement. Fireworks and other explosions can cause both thermal and chemical injuries.[7] Blast injuries should increase suspicion for full-thickness and penetrating injuries with possible intraocular foreign bodies.

Epidemiology

The worldwide incidence of ocular burns is largely unknown. Despite best efforts using available data, there is a knowledge gap regarding the worldwide incidence of ocular burns. The World Health Organization’s Blindness Data Bank describes the incidence of penetrating eye injuries and eye injuries leading to blindness but unfortunately does not include any data for ocular chemical burns.[8] Two United States databases, the American Academy of Ophthalmology (Academy) IRIS® Registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) and The Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, have provided some insight into the scope of this critical public health problem in the USA.[9]

Ocular chemical burns cause between 11.5 and 22.1% of eye injuries.[10] In 1999, approximately 280,000 work-related eye injuries were treated in United States’ emergency departments. Ocular chemical burns were the second most common injury behind ocular foreign bodies. Workers between the ages of 20 to 34 were at the highest risk of sustaining an ocular injury.[11] From 2010 to 2013, 144,419 cases of chemical ocular burns were treated at USA emergency departments. The median age was 32 years. Perhaps surprisingly, rates of injury were highest for children 1 to 2 years of age (28.61 and 23.49 injuries per 100,000 population, respectively). These numbers are extrapolated mainly from case series and have come under scrutiny due to large amounts of missing data, highlighting the need for epidemiologic studies.[12]

According to one database, alkali injuries (53.6%) were seen more commonly than acid injuries (46.4%).[1] Some sources suggest alkali burns outnumber acid burns almost 2 to 1. Ammonia-containing compounds are the most common cause of alkali burns, while sulfuric acid is the most common cause of acid burns.[13]

Pathophysiology

Acute tissue damage from ocular burns depends on several factors. These include the chemical and physical characteristics of the offending agent (mainly the pH), concentration, volume, temperature, the force of impact, and how the chemical interacts with ocular tissue. Alkaline agents are lipophilic and more likely to penetrate deeply into the eye than acidic agents. Alkaline chemical injuries cause liquefactive necrosis of tissue. As more superficial tissues undergo liquefaction, the chemical agent may penetrate deeply and damage intraocular structures such as the trabecular meshwork, lens, and ciliary body. Acidic agents coagulate proteins in superficial structures, limiting their penetration depth. Hydrofluoric acid is a notable exception to this and can cause damage to the anterior chamber structures. Despite their different characteristics and manners in interacting with ocular tissues, both acids and alkalis can cause severe tissue damage.[14]

The pathophysiology and disease course has been proposed to be divided into four distinct clinical phases: immediate, acute (0 to 7 days), early reparative (7 to 21 days), and late reparative (after 21 days).[15] For the sake of simplicity, others have chosen to classify the management of chemical ocular injuries into immediate, acute (<6 weeks), and chronic (>6 weeks) phases.[14]

Once the immediate insult has been attended to, care must be taken to initiate a therapeutic plan to minimize inflammation and promote re-epithelialization. Limbal and conjunctival ischemia, persistent inflammation, ocular surface exposure due to adnexal burns, and elevated intraocular pressure can inhibit re-epithelialization if not adequately managed. Specific therapeutic and surgical management of the underlying burn pathophysiology will be discussed in the treatment/management section.

History and Physical

Initial history and physical assessment in both the prehospital and hospital settings must address life threats to the patient while minimizing the risk of exposing care providers. Particular attention should be paid to addressing any immediate threat to the victim’s airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). Once the ABCs have been assessed, and no intervention is needed for initial stabilization, further assessment can continue. If the patient is conscious, with normal mental status, ongoing assessment can then be directed towards the exposure. While continuing further decontamination, the care team should gather information on what chemical agent(s) the victim was exposed to and the extent. Collecting more patient-specific details like medical history, medications, allergies, surgical history, last meal, etc., can be taken as ocular irrigation occurs. Once the patient has been stabilized and ocular irrigation has commenced, further investigation into the properties of the offending chemical agent(s) can ensue. Safety data sheets (SDS) and The Poison Control Center are available resources for more information on the acute management of dangerous chemical exposures.

Once the eyes and associated structures have been adequately irrigated and the pH of the ocular surface reaches neutral (7.0 to 7.2) by litmus paper assay, attention can be directed to assess how much of the ocular surface and associated structures are involved. Visual acuities should now be evaluated if possible. Pain due to superficial ocular nerves being exposed may cause significant blepharospasm and limit assessment. Applying a topical ocular anesthetic may be necessary prior to biomicroscopy (slit lamp evaluation). Particular attention should be given to the extent of limbal and conjunctival/episcleral ischemia, corneal clarity, and total surface area involved. Assessment of surface area involvement requires staining the eye with an agent such as sodium fluorescein. The extent and severity of involvement of these tissues have prognostic value.[14] During biomicroscopy, the examiner should look for evidence of ocular perforation. If there is no concern for a ruptured globe, the examiner can safely check intraocular pressure.

Evaluation

Typically, no imaging is indicated for ocular burns. If an intraocular foreign body is suspected based on the mechanism of injury (blast injury, for example), computed tomography imaging of the orbits may be helpful. Further imaging should be guided by the history and physical exam and clinical suspicion of other injuries.

Treatment / Management

In treating chemical ocular burns, the first step is immediate and thorough decontamination of the ocular surface and adnexa. If necessary, simultaneous decontamination of the rest of the body should occur with particular attention to the oropharynx to avoid inhalational injury. Removing and discarding affected clothing may be necessary. Care must be taken to prevent contaminating care providers during the initial decontamination process. If a commercially prepared sterile irrigating or amphoteric solution is available, these can be utilized for initial ocular lavage. In most cases, tap water will be the only available option in the prehospital setting. Tap water should be used despite the risk of worsening corneal edema due to its hypotonicity relative to the cornea. Tap water meets the basic requirements of an emergency irrigating solution.[16]

However, it must be stressed that the choice of irrigating solution is less important than the timing of treatment. Initiation of decontamination should never be delayed.[14] Once the patient arrives at the hospital, ocular irrigation must resume until the pH of the ocular surface is between 7.0 and 7.2. This may require 2 liters of irrigation for mild injuries and up to 10 liters for more severe injuries. Irrigation should continue for a minimum of 30 minutes. Severe injuries may take 2 to 4 hours of continuous irrigation for adequate decontamination. Alkali injuries will likely require more irrigation than acids to eliminate. Lactated Ringers is the most commonly used irrigating solution, given that it is readily available in the emergency department setting. Other solutions such as 0.9% sodium chloride (normal saline) or a balanced salt solution can also be used. Topical anesthesia can improve patient compliance with hospital-initiated irrigation. Once irrigation has been completed by ensuring the pH of the ocular surface is neutral using litmus paper, care must be taken to remove all particulate matter. Failure to remove particulate matter increases the risk of ongoing inflammation. Special care must be taken to remove particles from the superior fornix after single and double lid eversion. In cases of lime ocular injury in children (and uncooperative adults), an examination under anesthesia is mandatory. This will allow for adequate evaluation of the superior fornix and complete removal of the offending agent and residual particulate matter.[17] In severe eyelid burns, escharotomy may be necessary to allow for complete closure of eyelids to avoid exposure-related complications.

Management during the acute phase (days 0 to 7) and early reparative phase (days 8 to 21) is directed at suppressing inflammation and promoting ocular surface re-epithelialization. The severity of the injury will dictate how frequently the patient will need to be evaluated. A topical antibiotic ointment and preservative-free artificial tears may be sufficient for mild injuries. More severe injuries require frequent monitoring for complications like ocular surface exposure from adnexal scarring, corneal or stromal thinning, and elevated intraocular pressure. Topical steroids are used to decrease inflammation. Topical cycloplegic agents can be valuable to manage pain. Systemic pain medication may be needed in addition to topical therapy during the acute phase. Preservative-free artificial tears are used through all stages of healing. Systemic tetracyclines (doxycycline 20 to 50 mg PO twice daily) and vitamin C (1,000 mg PO daily) are prescribed to promote wound healing. Preservative-free topical antibiotics for infection prophylaxis may be started. Avoid aminoglycosides like topical gentamicin and tobramycin as these are particularly toxic to the corneal epithelium. Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment is well-tolerated, readily available, and a good choice for initial infection prophylaxis. Medications to decrease intraocular pressure may be needed throughout the continuum of care. Elevated intraocular pressure can impair corneal healing in the acute and early reparative phases and must be treated aggressively. Chronically elevated intraocular pressure can damage the optic nerve resulting in glaucomatous vision loss.[18]

More severe burns will require more specialized therapies such as topical biologics, including autologous serum and platelet-rich plasma drops. Bandage contact lenses are helpful for corneal epithelial defects and are very useful to modulate pain from exposed corneal nerves. When wounds are covered with a bandage contact lens, it is imperative to include antibiotic prophylaxis against Pseudomonas. More severe burns require consideration of early amniotic membrane transplant, preferably during the first week.[13] Tenonplasty can be successfully promoted to promote re-epithelialization in severe scleral melting or ischemia cases.[19]

During the late reparative phase (>21 days), management involves controlling inflammation and rehabilitation and reconstructing the ocular surface.[14] Conjunctival limbal autograft can restore limbal stem cells to provide healthy supporting tissue in anticipation of keratoplasty. Different types of keratoplasty can be performed depending on the depth of corneal scarring. The goal of keratoplasty is to improve visual function. If needed, symblepharon release and forniceal and lid reconstruction will occur during the late reparative phase in persistent ocular surface exposure, loss of other function, or cosmesis.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses of the red, painful eye include intraocular foreign body, ruptured globe, corneal or scleral laceration, corneal abrasion, infectious keratoconjunctivitis, uveitis, and superficial ocular foreign body. A focused history and physical exam will allow the clinician to differentiate chemical ocular injury from these other diagnoses.

Prognosis

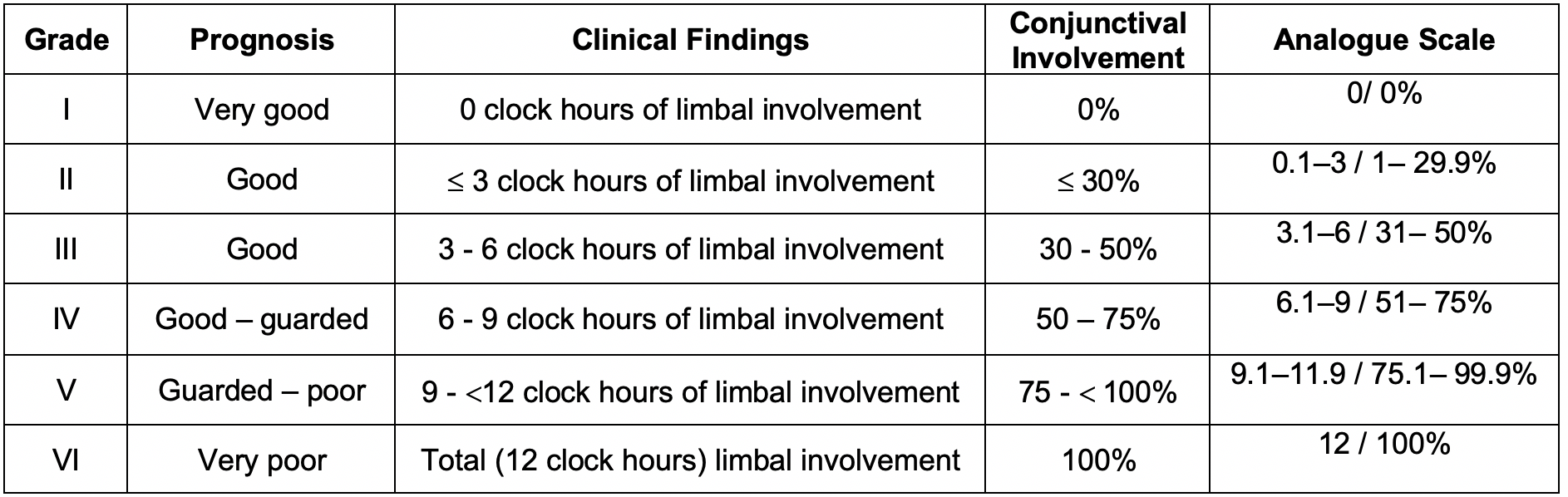

Two classification systems have been developed to assess prognosis based on early assessment and burn features. The Roper-Hall classification tool uses corneal clarity and amount of limbal ischemia to provide a grade from I-IV. Dua’s classification system uses the number of limbal clock hours involved and the percent of conjunctival involvement to provide a grade from I to VI. The higher the number, the poorer the prognosis for both classification systems.[14] It should be noted that the Roper-Hall classification was first introduced in 1965, while the Dua classification was first published in 2001.

Since these classification systems were introduced, medical advances have improved outcomes, but they still allow for assessing injury severity and prognosis. A hazy cornea, extensive limbal ischemia, and more conjunctival involvement portend a poorer prognosis. It is important to note that the amount of limbal ischemia may not be easily assessed at the time of original injury by simply looking at the blanching of limbal vessels and may only be appreciated by frequent examinations of the stained limbus.[13] The more limbal ischemia, the greater the risk for conjunctivalization of the cornea. Conjunctivilization is when the cornea becomes covered by tissue more similar to the conjunctival epithelium resulting in corneal opacification.[20]

Complications

- Infectious keratitis

- Glaucoma

- Corneal/stromal melting and perforation

- Permanent vision loss

- Chronic inflammation and pain

- Sympathetic ophthalmia

- Hypotony

- Cataracts

Consultations

Ophthalmology inevitably will be called upon for an acute chemical burn to the eye or ocular adnexa. Plastic surgery, ENT, or OMFS consultation may be needed in cases of associated facial burns.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Injury prevention in the home involves limiting access to dangerous chemicals by young children. Childproofing the home to ensure a safe environment requires healthcare providers of all types to educate parents of infants and young children on the importance of injury prevention. Injury prevention in the workplace is multifaceted and requires adequate personal protective equipment when handling chemicals and worker knowledge of the chemicals with which they work. Onsite decontamination capabilities are required by law, and workers must know where they are and how to use them in case of exposure. Periodic hazardous materials training to include decontamination techniques should be offered where dangerous chemical exposures may occur.

Pearls and Other Issues

The main pitfall of initial management is inadequate irrigation resulting in ongoing exposure to the chemical. Another pitfall in the immediate stage of the injury is not debriding particulate matter from the eye, particularly from the superior fornix. Residual particulate matter causes persistent inflammation. A valuable tool to help manage the initial hospital-based irrigation is a commercially available lens that can be applied to the eye and connected to intravenous line tubing to allow hands-free irrigation. If such a commercial lens is not available, adequate, timely irrigation will require an attendant present at the patient’s side to thoroughly irrigate the ocular surface. Topical anesthesia is almost always necessary during irrigation and assessment.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The continuum of care for an ocular chemical burn may start with activating emergency medical services. Prehospital providers must ensure a safe environment for themselves and the injured patient by performing adequate decontamination. Early communication with the hospital-based team must include information about patient stability, mental status, any concerns for airway involvement, the suspected extent of injury, and information about the chemical agent if known. This will allow for the emergency department to be prepared for patient arrival. After the acute care providers have stabilized the patient, adequately irrigated the eyes, decontaminated the patient, and assessed the extent of injuries, a call must be placed to ophthalmology to discuss further care. Early consultation with ophthalmology will optimize patient care in the immediate stage when initial care is being provided by a generalist like the emergency medicine physician. Coordinated care with the hospital pharmacist may be needed to ensure the patient has access to the appropriate therapeutic agents in the early acute phase of the injury.