[1]

Bahn RS. Graves' ophthalmopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2010 Feb 25:362(8):726-38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905750. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20181974]

[2]

Eckstein AK,Plicht M,Lax H,Neuhäuser M,Mann K,Lederbogen S,Heckmann C,Esser J,Morgenthaler NG, Thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies are independent risk factors for Graves' ophthalmopathy and help to predict severity and outcome of the disease. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2006 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 16835285]

[3]

Şahlı E, Gündüz K. Thyroid-associated Ophthalmopathy. Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Apr:47(2):94-105. doi: 10.4274/tjo.80688. Epub 2017 Apr 1

[PubMed PMID: 28405484]

[4]

Valyasevi RW, Erickson DZ, Harteneck DA, Dutton CM, Heufelder AE, Jyonouchi SC, Bahn RS. Differentiation of human orbital preadipocyte fibroblasts induces expression of functional thyrotropin receptor. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1999 Jul:84(7):2557-62

[PubMed PMID: 10404836]

[5]

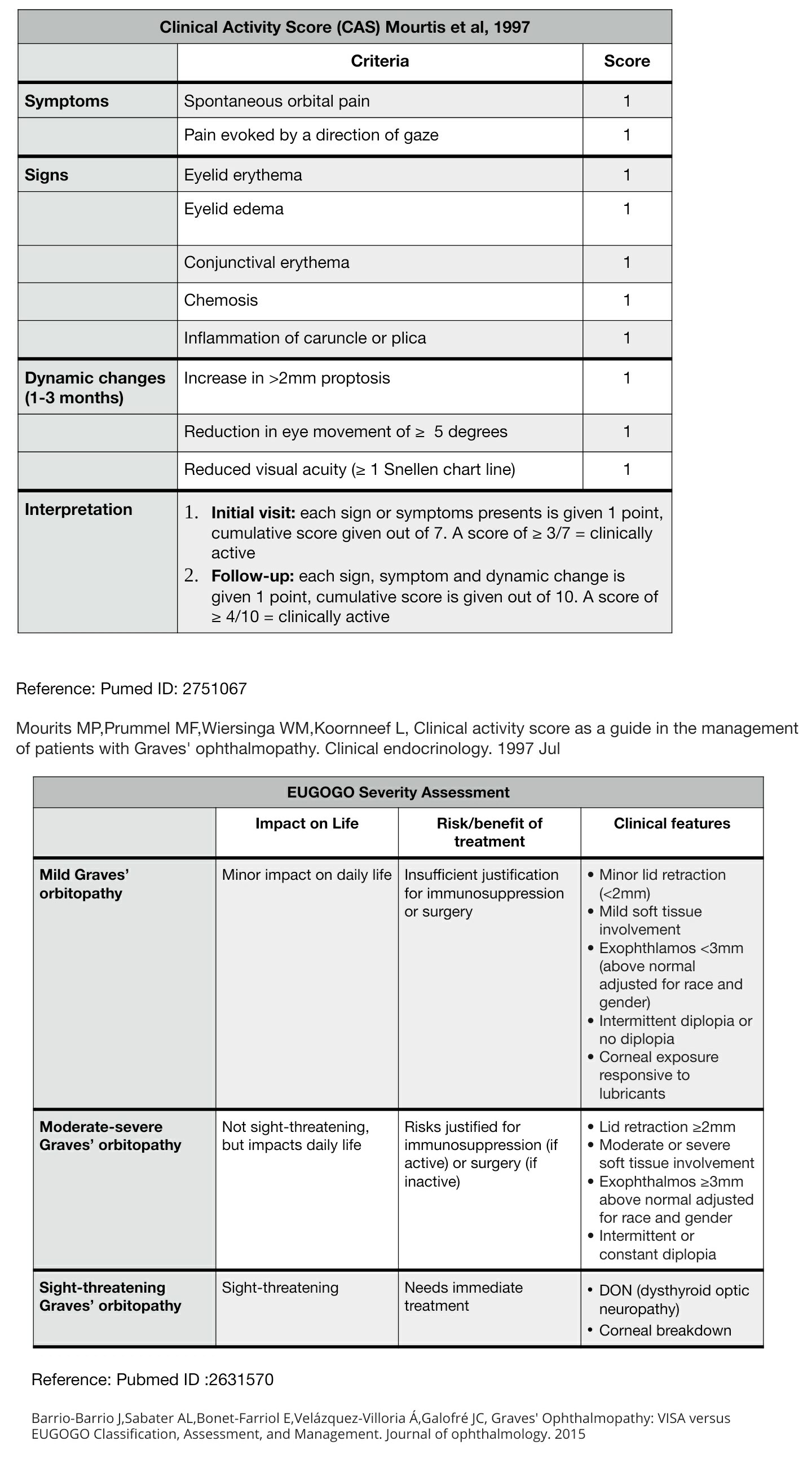

Barrio-Barrio J, Sabater AL, Bonet-Farriol E, Velázquez-Villoria Á, Galofré JC. Graves' Ophthalmopathy: VISA versus EUGOGO Classification, Assessment, and Management. Journal of ophthalmology. 2015:2015():249125. doi: 10.1155/2015/249125. Epub 2015 Aug 17

[PubMed PMID: 26351570]

[6]

Tanda ML, Piantanida E, Liparulo L, Veronesi G, Lai A, Sassi L, Pariani N, Gallo D, Azzolini C, Ferrario M, Bartalena L. Prevalence and natural history of Graves' orbitopathy in a large series of patients with newly diagnosed graves' hyperthyroidism seen at a single center. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013 Apr:98(4):1443-9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3873. Epub 2013 Feb 13

[PubMed PMID: 23408569]

[7]

Hiromatsu Y,Eguchi H,Tani J,Kasaoka M,Teshima Y, Graves' ophthalmopathy: epidemiology and natural history. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2014;

[PubMed PMID: 24583420]

[8]

Villadolid MC, Yokoyama N, Izumi M, Nishikawa T, Kimura H, Ashizawa K, Kiriyama T, Uetani M, Nagataki S. Untreated Graves' disease patients without clinical ophthalmopathy demonstrate a high frequency of extraocular muscle (EOM) enlargement by magnetic resonance. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1995 Sep:80(9):2830-3

[PubMed PMID: 7673432]

[9]

Dickinson AJ, Perros P. Controversies in the clinical evaluation of active thyroid-associated orbitopathy: use of a detailed protocol with comparative photographs for objective assessment. Clinical endocrinology. 2001 Sep:55(3):283-303

[PubMed PMID: 11589671]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[10]

Saraci G, Treta A. Ocular changes and approaches of ophthalmopathy in basedow - graves- parry- flajani disease. Maedica. 2011 Apr:6(2):146-52

[PubMed PMID: 22205899]

[11]

Werner SC. Modification of the classification of the eye changes of Graves' disease. American journal of ophthalmology. 1977 May:83(5):725-7

[PubMed PMID: 577380]

[12]

Mourits MP, Prummel MF, Wiersinga WM, Koornneef L. Clinical activity score as a guide in the management of patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy. Clinical endocrinology. 1997 Jul:47(1):9-14

[PubMed PMID: 9302365]

[13]

Kirsch E, von Arx G, Hammer B. Imaging in Graves' orbitopathy. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2009:28(4):219-25

[PubMed PMID: 19839878]

[14]

Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, Bartalena L, Prummel M, Stahl M, Altea MA, Nardi M, Pitz S, Boboridis K, Sivelli P, von Arx G, Mourits MP, Baldeschi L, Bencivelli W, Wiersinga W, European Group on Graves' Orbitopathy. Selenium and the course of mild Graves' orbitopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 May 19:364(20):1920-31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012985. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21591944]

[15]

Chiovato L, Latrofa F, Braverman LE, Pacini F, Capezzone M, Masserini L, Grasso L, Pinchera A. Disappearance of humoral thyroid autoimmunity after complete removal of thyroid antigens. Annals of internal medicine. 2003 Sep 2:139(5 Pt 1):346-51

[PubMed PMID: 12965943]

[16]

Laurberg P, Wallin G, Tallstedt L, Abraham-Nordling M, Lundell G, Tørring O. TSH-receptor autoimmunity in Graves' disease after therapy with anti-thyroid drugs, surgery, or radioiodine: a 5-year prospective randomized study. European journal of endocrinology. 2008 Jan:158(1):69-75. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0450. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18166819]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[17]

Tu X, Dong Y, Zhang H, Su Q. Corticosteroids for Graves' Ophthalmopathy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed research international. 2018:2018():4845894. doi: 10.1155/2018/4845894. Epub 2018 Nov 22

[PubMed PMID: 30596092]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[18]

Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Campi I, Rossi S, Bonara P, Sbrozzi F, Guastella C, Avignone S, Pirola G, Ratiglia R, Beck-Peccoz P. Efficacy of rituximab treatment for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy as a result of intraorbital B-cell depletion in one patient unresponsive to steroid immunosuppression. European journal of endocrinology. 2006 Apr:154(4):511-7

[PubMed PMID: 16556712]

[19]

Ye X, Bo X, Hu X, Cui H, Lu B, Shao J, Wang J. Efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with active moderate-to-severe Graves' orbitopathy. Clinical endocrinology. 2017 Feb:86(2):247-255. doi: 10.1111/cen.13170. Epub 2016 Sep 7

[PubMed PMID: 27484048]

[20]

Smith TJ, Kahaly GJ, Ezra DG, Fleming JC, Dailey RA, Tang RA, Harris GJ, Antonelli A, Salvi M, Goldberg RA, Gigantelli JW, Couch SM, Shriver EM, Hayek BR, Hink EM, Woodward RM, Gabriel K, Magni G, Douglas RS. Teprotumumab for Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 May 4:376(18):1748-1761. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614949. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28467880]

[21]

Douglas RS, Kahaly GJ, Patel A, Sile S, Thompson EHZ, Perdok R, Fleming JC, Fowler BT, Marcocci C, Marinò M, Antonelli A, Dailey R, Harris GJ, Eckstein A, Schiffman J, Tang R, Nelson C, Salvi M, Wester S, Sherman JW, Vescio T, Holt RJ, Smith TJ. Teprotumumab for the Treatment of Active Thyroid Eye Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2020 Jan 23:382(4):341-352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910434. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31971679]

[22]

Garrity JA, Fatourechi V, Bergstralh EJ, Bartley GB, Beatty CW, DeSanto LW, Gorman CA. Results of transantral orbital decompression in 428 patients with severe Graves' ophthalmopathy. American journal of ophthalmology. 1993 Nov 15:116(5):533-47

[PubMed PMID: 8238212]

[23]

Ogura JH, Thawley SE. Orbital decompression of exophthalmos. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 1980 Feb:13(1):29-38

[PubMed PMID: 7367005]

[24]

Garrity JA. Orbital lipectomy (fat decompression) for thyroid eye disease: an operation for everyone? American journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Mar:151(3):399-400. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.10.036. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21335108]

[25]

San Miguel I, Arenas M, Carmona R, Rutllan J, Medina-Rivero F, Lara P. Review of the treatment of Graves' ophthalmopathy: The role of the new radiation techniques. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2018 Apr-Jun:32(2):139-145. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2017.09.003. Epub 2017 Sep 21

[PubMed PMID: 29942184]

[26]

Gogakos AI, Boboridis K, Krassas GE. Pediatric aspects in Graves' orbitopathy. Pediatric endocrinology reviews : PER. 2010 Mar:7 Suppl 2():234-44

[PubMed PMID: 20467370]

[27]

Stafford IP, Dildy GA 3rd, Miller JM Jr. Severe Graves' ophthalmopathy in pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005 May:105(5 Pt 2):1221-3

[PubMed PMID: 15863589]

[28]

Boddu N, Jumani M, Wadhwa V, Bajaj G, Faas F. Not All Orbitopathy Is Graves': Discussion of Cases and Review of Literature. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2017:8():184. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00184. Epub 2017 Jul 31

[PubMed PMID: 28824545]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[29]

Stiebel-Kalish H, Robenshtok E, Hasanreisoglu M, Ezrachi D, Shimon I, Leibovici L. Treatment modalities for Graves' ophthalmopathy: systematic review and metaanalysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2009 Aug:94(8):2708-16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0376. Epub 2009 Jun 2

[PubMed PMID: 19491222]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[30]

Ratanakorn D, Vejjajiva A. Long-term follow-up of myasthenia gravis patients with hyperthyroidism. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 2002 Aug:106(2):93-8

[PubMed PMID: 12100368]

[31]

Yeh HH, Tung YW, Yang CC, Tung JN. Myasthenia gravis with thymoma and coexistent central hypothyroidism. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association : JCMA. 2009 Feb:72(2):91-3. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70030-9. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19251538]