Continuing Education Activity

Skin grafting is a closure technique used in dermatology most commonly to close wounds created by the removal of skin cancer. Although currently less favored than flap closures, grafting can produce a good cosmetic result. Skin grafts, in contrast to flaps, are completely removed from their blood supply, whereas flaps remain attached to a blood supply via a pedicle. Skin grafts are less technically difficult but can be more time-consuming as the procedure creates a second surgical site. This activity reviews the indications, contraindications of skin grafts and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing these patients before and after surgery.

Objectives:

- Identify the differences between split thickness and full thickness skin grafts.

- Describe the indications for skin grafts.

- Recall the preparation of the donor and recipient sites for skin grafts.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients undergoing skin grafts.

Introduction

Skin grafting is a closure technique used in dermatology most commonly to close wounds created by the removal of skin cancer. Although currently less favored than flap closures, grafting can produce a good cosmetic result. Skin grafts, in contrast to flaps, are completely removed from their blood supply, whereas flaps remain attached to a blood supply via a pedicle. Skin grafts are less technically difficult but can be more time-consuming as the procedure creates a second surgical site. Skin grafts can be divided into several categories based on the composition of the graft with each type of graft having unique risks and indications.

- Split-thickness skin grafts (STSG) are composed of the epidermis and a superficial part of the dermis.

- Full-thickness skin grafts (FTSG) contain both the full epidermis and dermis.

- Composite grafts contain skin and another type of tissue, usually cartilage.

Full-thickness skin grafts are the most commonly used graft in dermatology. FTSGs can provide an excellent tissue match for the host site and heal with minimal scarring and contracture. Composite grafts also have a high metabolic demand and typically are only used in the nose and ear in situations where cartilage also needs to be replaced. Split-thickness grafts are typically less cosmetically appealing due to a lack of adnexal structures and color mismatch. There is also a significant risk of contracture with STSG. Split-thickness graft donor sites also tend to be more painful for the patient compared to FTSG.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Grafting requires a good vascular supply for the survival of the tissue and a good donor match for an acceptable cosmetic result. Donor sites should match in the thickness, color, texture, and adnexal structures. Donor sites should match the actinic damage of the graft site as well, but it is more important the area be free of cancerous and precancerous lesions.[1] If possible, donor sites should not transfer hair-bearing skin to non-hair-bearing areas. Epilation can be used to remove unwanted hair growth after the graft has healed. Common donor sites for facial FTSG are supraclavicular, preauricular, postauricular, and inner arm. The conchal bowl is a good source of sebaceous skin for grafts of the nose.[1][2] Donor sites for STSG are typically the trunk, buttock, thighs, or inner arm.[3]

Indications

In general, surgeons should choose the simplest closure that will provide the best cosmetic result. Grafts are typically considered when secondary intent, primary closure, or flap closure are not adequate for closing the wound.[4]

Split-Thickness Skin Grafts

Split-thickness skin grafts are indicated for large wounds and can survive on relatively avascular sites where an FTSG would typically fail. STSGs are typically reserved for sites that are too large for an FTSG or flap.[1]

Full-Thickness Skin Grafts

Full-thickness skin grafts are indicated for small avascular areas less than 1 cm or for larger areas with good blood supply as the metabolic demands of the additional adnexal structures of FTSG increase the likelihood of necrosis.[5] Large grafts over bone or cartilage without any intervening tissue are prone to failure. Delayed grafting or using hinge flaps to cover the exposed avascular tissue are some options to allow for placement of FTSG.

Composite Grafts

Composite grafts are indicated in situations where a donor site has lost underlying muscle or bone. The most common composite graft in dermatologic surgery are grafts containing cartilage used to reinforce the nose or ear.[1]

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for grafting include incomplete removal of cancer, active infection, and uncontrolled bleeding.

Relative contraindications include smoking, an anticoagulant medication, bleeding disorder, chronic corticosteroids, or malnutrition.[6]

Split-thickness skin grafts should not be used near free margins due to their increased risk of contracture.

Full-thickness skin grafts should not be used on an avascular site greater than 1 cm.[5]

Technique or Treatment

Full-Thickness Skin Graft

After selection of a donor site, both sites are sterilely prepped, draped, and anesthetized. A template of the defect can be made using a gauze, measurements or foil from the suture packaging. This template is then transposed onto the donor site. Classically, the donor site should be closed with a length to width ratio of 3:1, but Wang et al.[7] suggested that this ratio may not be necessary for donor sites, which could leave smaller donor defects. Some debate exists in the literature on the proper sizing of the graft. In general, grafts are oversized by 10% to 20% to allow for contraction and to allow contouring of the graft.[8] However, some others have suggested that grafts should be undersized by up to 10% to 20% to prevent puckering or pincushioning of the graft.[9] This suggests that there is leeway in terms of graft size, especially when grafts that are too small can be meshed to increase the size of the graft. FTSG can be harvested using a standard excision technique. After the graft is removed, it is placed in sterile saline while hemostasis is achieved at the donor site. The graft is subsequently defatted using a scalpel or scissors. An alternative method would be to take the deep margin of the graft just above the subcutaneous fat, which eliminates the defatting step. The graft should be contoured to the size of the defect and placed in the wound bed as quickly as possible. It is imperative that the graft is placed in apposition to the wound bed to reduce the risk of graft failure. Typically, grafts are sutured with a quickly absorbing suture, such as chromic gut or a non-absorbable suture such as nylon. For large grafts or at the preference of the surgeon, basting sutures can be placed. Basting suture should be placed first to allow for hemostasis of bleeding induced by suture placement. After hemostasis of the wound bed is achieved, the graft edges are sutured into place with an emphasis placed on apposition of the wound bed and graft. After the graft is sutured in place, a bolster is placed over the graft to further assist in apposition. A variety of different products are available to use as bolsters, such as petroleum impregnated gauze. The bolster and overlying pressure dressing are used to secure the graft in place and to prevent desiccation of the graft. The bolster and pressure dressing can be removed in 1 week followed by removal of nonabsorbable sutures, if they are used, in approximately 2 weeks.

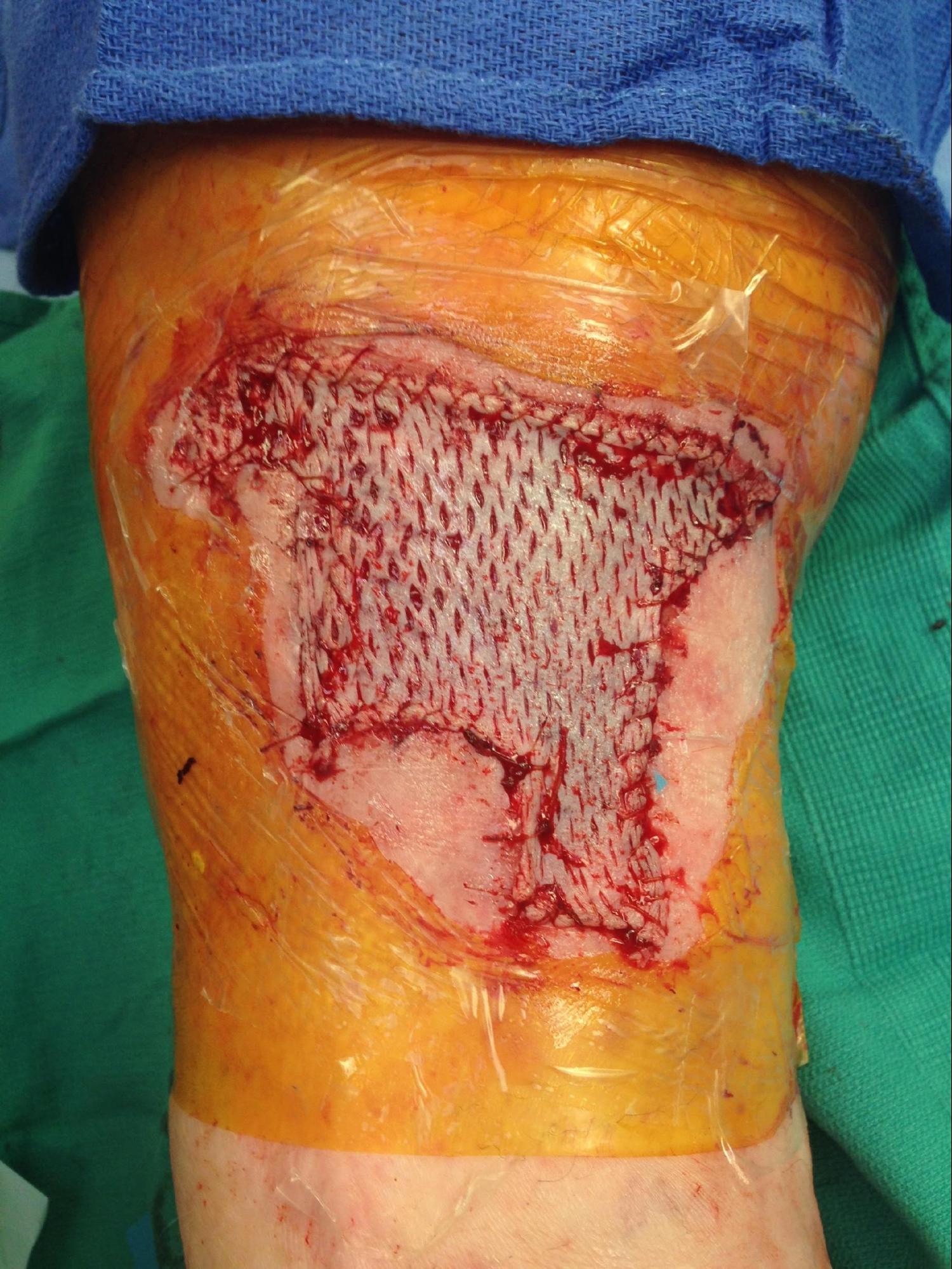

Split-Thickness Skin Grafts

There are a variety of techniques and tools available to the dermatologic surgeon performing an STSG. In general, the skin is sterilely prepped and then thoroughly cleansed with sterile saline to wash off the antiseptic and prevent desiccation. The area is then anesthetized. For powered dermatomes, mineral oil or antibiotic ointment can be used to lubricate and hydrate the skin. An STSG includes the epidermis and part of the dermis. Some devices allow the surgeon to set the desired thickness for the graft. The dermatome applied firmly against the skin with downward and forward pressure. An assistant can use forceps to gently grasp and apply traction to prevent the graft from folding in on itself. If desired, the graft can be subsequently meshed; meshing in favored in larger grafts. The graft is then applied to the defect and contoured to fit the defect. The graft is then anchored in place using sutures or staples depending on physician preference. A bolster is applied over the graft. The donor site can be treated like an abrasion and covered with petrolatum and a bandage.

Complications

All patients undergoing skin grafting should be educated on the risk of graft failure. Grafts are nourished initially by imbibition of nutrients in the wound bed followed by revascularization.[10][11] If a graft's metabolic demands are too high or if the graft is separated from the wound bed, the graft could fail. Lack of wound bed/graft apposition, trauma, infection, hematoma/seroma formation increases the risk of graft failure. The connection between the wound bed and graft is very fragile and prone to disruption by shearing forces. Meticulous hemostasis can help prevent hematoma formation. Seromas can be avoided with basting sutures, used in large grafts, and as well as meshing the graft. Meshing is a process where one or more incisions are made into the graft. This can also be used to increase the size of the graft. Infection increases the oxidative stress on the graft as well as potentially disrupting the wound bed with abscess formation.

Impending graft failure can be indicated by a porcelain white graft or overly black eschar typically seen 1-2 weeks after grafting. These findings, however, may only indicate superficial necrosis with the survival of the dermal component of the graft. Therefore, debridement is very rarely indicated shortly after grafting. The patient should be made aware that several weeks after grafting the superficial sloughing or necrosis can be replaced by healthy tissue. Failed grafts should be left in place as they can act as a biologic dressing over the wound which will heal via secondary intention.

The risk of contracture is more significant in split-thickness skin grafts compared to FTSG. Due to this risk, split-thickness grafts should not be used near free margins.[1]

Clinical Significance

Proper skin grafting closure technique will result in successfully closed wounds created by the removal of skin cancer. Although currently less favored than flap closures, grafting can produce a good cosmetic result.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Other health care professionals can decrease morbidity by recognizing and referring complications either to the surgeon or another specialist in skin surgery. A majority of the evidence for skin grafting is based on case series and expert option. (Level V)