Continuing Education Activity

In spite of breakthroughs in diagnosis, treatment, and vaccination, in 2015 there were 8.7 million reported cases of meningitis worldwide with 379,000 subsequent deaths. This activity reviews the cause, presentation, and diagnosis of meningitis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Review the causes of meningitis.

- Describe the presentation of a patient with meningitis.

- Summarize the treatment of meningitis.

- Describe modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by meningitis.

Introduction

Signs and symptoms of meningeal inflammation have been recorded in countless ancient texts throughout history; however, the term 'meningitis' came into general usage after surgeon John Abercrombie defined it in 1828.

Despite breakthroughs in diagnosis, treatment, and vaccination, in 2015, there were 8.7 million reported cases of meningitis worldwide, with 379,000 subsequent deaths.[1][2][3]

Meningitis is a life-threatening disorder that is most often caused by bacteria or viruses. Before the era of antibiotics, the condition was universally fatal. Nevertheless, even with great innovations in healthcare, the condition still carries a mortality rate of close to 25%.

Etiology

Meningitis is defined as inflammation of the meninges. The meninges are the three membranes (the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater) that line the vertebral canal and skull enclosing the brain and spinal cord. Encephalitis, on the other hand, is inflammation of the brain itself.[4][5]

Meningitis can be caused by infectious and non-infectious processes (autoimmune disorders, cancer/paraneoplastic syndromes, drug reactions).

The infectious etiologic agents of meningitis include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and less commonly parasites.

Risk factors for meningitis include:

- Chronic medical disorders (renal failure, diabetes, adrenal insufficiency, cystic fibrosis)

- Extremes of age

- Undervaccination

- Immunosuppressed states (iatrogenic, transplant recipients, congenital immunodeficiencies, AIDS)

- Living in crowded conditions

- Exposures:

- Travel to endemic areas (Southwestern U.S. for cocci; Northeastern U.S. for Lyme disease)

- Vectors (mosquitoes, ticks)

- Alcohol use disorder

- Presence of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt

- Bacterial endocarditis

- Malignancy

- Dural defects

- IV drug use

- Sickle cell anemia

- Splenectomy

Epidemiology

In the United States, the annual incidence of bacterial meningitis is approximately 1.38 cases/100,000 population with a case fatality rate of 14.3%. [6]

The highest incidence of meningitis worldwide is in an area of sub-Saharan Africa dubbed “the meningitis belt” stretching from Ethiopia to Senegal.[7][2][8]

Most common bacterial causes of meningitis in the United States are: [9]

- Streptococcus pneumoniae (incidence in 2010: 0.3/100,000)

- group B Streptococcus

- Neisseria meningitidis (incidence in 2010: 0.123/100,000)

- Haemophilus influenzae (incidence in 2010: 0.058/100,000)

- Listeria monocytogenes

Consider less common bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus in patients with recent surgery, central lines, and trauma. Mycobacterium tuberculosis should be considered in immunocompromised hosts. Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with travel to Lyme endemic areas. Treponema pallidum in HIV/AIDS and individuals with multiple sexual partners. Escherichia coli is an important pathogen in the neonatal period.

The most common viral agents of meningitis are non-polio enteroviruses (group b coxsackievirus and echovirus). Other viral causes: mumps, Parechovirus, Herpesviruses (including Epstein Barr virus, Herpes simplex virus, and Varicella-zoster virus), measles, influenza, and arboviruses (West Nile, La Crosse, Powassan, Jamestown Canyon)

Fungal meningitis typically is associated with an immunocompromised host (HIV/AIDS, chronic corticosteroid therapy, and patients with cancer).

Fungi causing meningitis include:

- Cryptococcus neoformans

- Coccidioides immitis

- Aspergillus

- Candida

- Mucormycosis (more common in patients with diabetes mellitus and transplant recipients; direct extension of sinus infection)

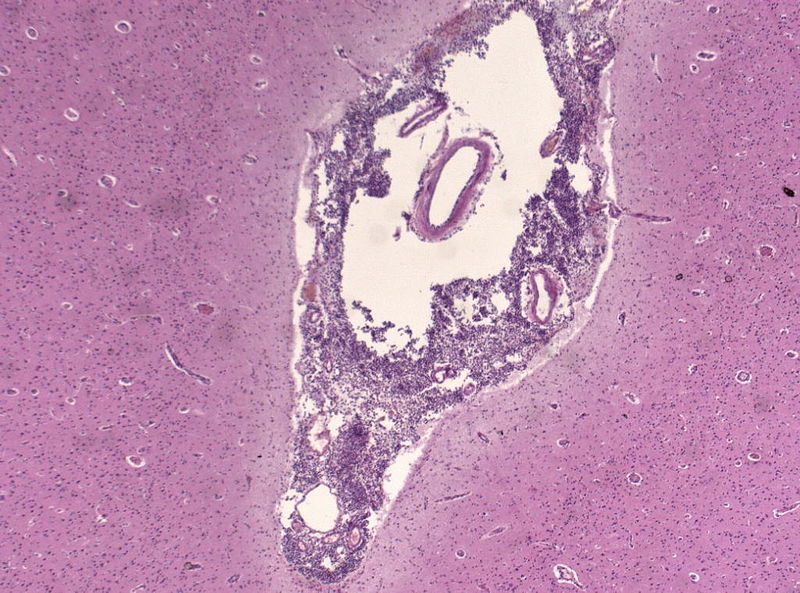

Pathophysiology

Meningitis typically occurs through two routes of inoculation:

Hematogenous seeding

- Bacteria colonize the nasopharynx and enter the bloodstream after mucosal invasion. Upon making their way to the subarachnoid space, the bacteria cross the blood-brain barrier, causing a direct inflammatory and immune-mediated reaction.

Direct contiguous spread

- Organisms can enter the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) via neighboring anatomic structures (otitis media, sinusitis), foreign objects (medical devices, penetrating trauma), or during operative procedures.

Viruses can penetrate the central nervous system (CNS) via retrograde transmission along neuronal pathways or by hematogenous seeding.

History and Physical

Meningitis can have a varied clinical presentation depending on age and immune status of the host. Symptoms typically include fever, neck pain/stiffness, and photophobia. More non-specific symptoms include headache, dizziness, confusion, delirium, irritability, and nausea/vomiting. Signs of increased intracranial pressure (altered mental status, neurologic deficits, and seizures) portend a poor prognosis.

The following risk factors should increase clinical suspicion:

- Close contact exposures (military barracks, college dorms)

- Incomplete vaccinations

- Immunosuppression

- Children younger than five years and adults older than 65 years

- Alcohol use disorder

One should try to determine a history of exposures, sexual contact, animal contact, previous neurosurgical intervention, recent travel, and the season. Most viral cases tend to occur in the warmer months.

In adults, the physical exam is centered on identifying focal neurologic deficits, meningeal irritation (Brudzinski and Kernig signs), and particularly in meningococcal meningitis, characteristic skin lesions (petechiae and purpura). Cranial nerve abnormalities are seen in 10%-20% of patients.

Signs and symptoms are less evident in neonates and infants. They can present with and without fever or hypothermia, decreased oral intake, altered mental status, irritability, bulging fontanelle. It is important to obtain a full perinatal history and vaccine records. Some causes of meningitis are vaccine-preventable such as Pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae type B, Meningococcus, Measles, and Varicella-virus.

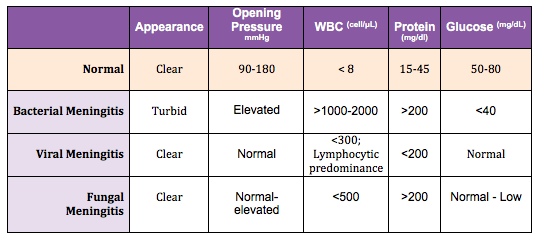

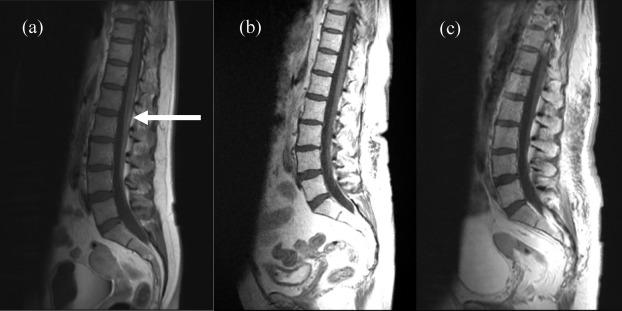

Evaluation

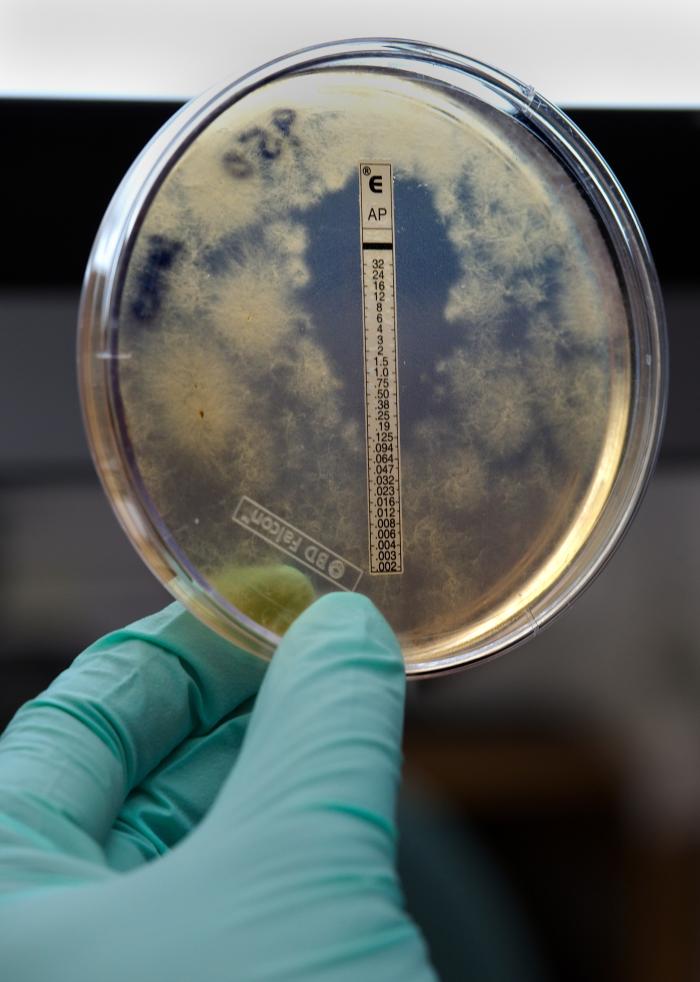

Meningitis is diagnosed through cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, which includes white blood cell count, glucose, protein, culture, and in some cases, polymerase chain reaction (PCR). CSF is obtained via a lumbar puncture (LP), and the opening pressure can be measured. [10][11][12]

Additional testing should be performed tailored on suspected etiology:

- Viral: Multiplex and specific PCRs

- Fungal: CSF fungal culture, India ink stain for Cryptococcus

- Mycobacterial: CSF Acid-fast bacilli smear and culture

- Syphilis: CSF VDRL

- Lyme disease: CSF burgdorferi antibody

The CSF findings expected in bacterial, viral, and fungal meningitis are listed in the chart: Expected CSF findings in bacterial versus viral versus fungal meningitis.

Ideally, the CSF sample should be obtained before initiating antimicrobials. However, when the diagnosis of bacterial meningitis is seriously considered, and the patient is severely ill, antibiotics should be initiated before performing the LP.

Computed Tomography (CT) of the Head before Lumbar Puncture

There is controversy regarding the adage that the lumbar puncture is the inciting event causing brain herniation and death in the setting of increased intracranial pressure caused by acute bacterial meningitis.

Currently, guidelines recommend empiric antibiotics and supportive care, while forgoing the lumbar puncture if there is clinical suspicion of increased intracranial pressure or impending brain herniation.

Signs and symptoms of impending herniation include:

- Glasgow coma scale (GCS) less than 11

- Lethargy

- Altered mental status

- New-onset seizures

- Focal neurologic deficit

It is important to note that a normal head CT does not preclude increased intracranial pressure or impending brain herniation. If the clinical symptoms are consistent with impending herniation, regardless of whether or not the CT head is normal, avoid the LP and start treatment.

Blood work should include blood culture, serum electrolytes as the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) is not uncommon, serum glucose, renal and liver function, and testing for HIV.

Treatment / Management

Antibiotics and supportive care are critical in all cases of bacterial meningitis.[13][14][15]

Managing the airway, maintaining oxygenation, giving sufficient intravenous fluids while providing fever control are parts of the foundation of meningitis management.

The type of antibiotic is based on the presumed organism causing the infection. The clinician must take into account patient demographics and past medical history in order to provide the best antimicrobial coverage.

Current Empiric Therapy

Neonates - Up to 1 month old

- Ampicillin intravenously (IV) and

- Cefotaxime (or equivalent, usually ceftazidime or cefepime) IV or gentamicin IV and

- Acyclovir IV

More than 1 month old

- Ampicillin IV and

- Ceftriaxone IV

Adults (18 to 49 years old)

- Ceftriaxone IV and

- Vancomycin IV

Adults older than 50 years old and the immunocompromised

- Ceftriaxone IV and

- Vancomycin IV and

- Ampicillin IV

Meningitis associated with a foreign body (post-procedure, penetrating trauma)

- Cefepime IV or ceftazidime IV or meropenem IV and

- Vancomycin IV

Meningitis with severe penicillin allergy

- Moxifloxacin IV and

- Vancomycin IV

Fungal (Cryptococcal) meningitis

- Amphotericin B IV and

- Flucytosine by mouth

Antibiotics

Ceftriaxone

- Third-generation cephalosporin

- Gram-negative coverage

- Very effective against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis

- Better CNS penetration than piperacillin-tazobactam (typically used in gram-negative sepsis coverage)

Vancomycin

- Gram-positive coverage (MRSA)

- Also used for resistant pneumococcus

Ampicillin

- Listeria coverage (gram-positive bacilli)

Cefepime

- Fourth-generation cephalosporin

- Increased activity against pseudomonas

Cefotaxime

- Third-generation cephalosporin

- Equivalent to ceftriaxone

- Safe for neonates

Steroid Therapy

There is insufficient evidence to support the widespread use of steroids in bacterial meningitis. Some studies report a reduction in mortality for Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis, but not in Haemophilus influenzae or Neisseria meningitidis meningitis. In children, steroids were associated with a reduction of severe hearing impairment only in cases of Haemophilus influenzae meningitis. [16]

Increased Intracranial Pressure

If the patient develops clinical signs of increased intracranial pressure (altered mental status, neurologic deficits, non-reactive pupils, bradycardia), interventions to maintain cerebral perfusion include:

- Elevating the head of the bed to 30 degrees

- Inducing mild hyperventilation in the intubated patient

- Osmotic diuretics such as 25% mannitol or 3% saline

Chemoprophylaxis

Chemoprophylaxis is indicated for close contacts of a patient diagnosed with N. meningitidis and H. influenzae type B meningitis.

Close contacts include housemates, significant others, those who have shared utensils, and health care providers in proximity to secretions (providing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, intubating without a facemask).

Antibiotic chemoprophylaxis for N. meningitidis includes rifampin, ciprofloxacin, or ceftriaxone, and for H. influenzae type B: rifampin.

Differential Diagnosis

- Stroke

- Subdural hematoma

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Metastatic brain disease

- Brain abscess (might coexist with meningitis)

Prognosis

Outcomes depend on patient characteristics such as age and immune status, but also vary depending on the etiologic organism. In the United States, for overall bacterial meningitis, the annual case fatality rate in 2010 was 14.3%.

Pathogen-specific mortality:[6]

- Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis: case fatality rate, 17.9%

- Neisseria meningitidis meningitis: case fatality rate, 10.1%

- Group B Streptococcus meningitis: case fatality rate, 11.1%

- H. influenzae meningitis: case fatality rate, 7%

- Listeria monocytogenes meningitis: case fatality rate, 18.1%

Complications

A metaanalysis published in 2010 from a cohort of pediatric patients reported that the median risk of sequelae post-discharge was 19.9%. In this study, the most common organism isolated was H. influenzae, followed by S. pneumoniae. The most common sequelae were hearing loss (6%), followed by behavioral (2.6%) and cognitive difficulties (2.2%), motor deficit (2.3%), seizure disorder (1.6%) and visual impairment (0.9%). [17]

Other complications include:

- Increased intracranial pressure from cerebral edema caused by increased intracellular fluid in the brain. Several factors are involved in the development of cerebral edema: increased in blood-brain barrier permeability, cytotoxicity from cytokines, immune cells, and bacteria.

- Hydrocephalus

- Cerebrovascular complications

- Focal neurologic deficits

Consultations

- Infectious diseases specialist in case of unidentified or rare pathogen

- Neurology to aid in seizure management

- Neurosurgery when there is suspicion of progression to brain abscess

- Rheumatology and heme/oncology in case of non-infectious cause

Pearls and Other Issues

Differentiating between bacterial, viral, and fungal meningitis may be difficult. CSF analysis may not be conclusive, and cultures do not immediately yield an answer. Multiplex and specific PCR panels are available and provide information in a few hours. Given the morbidity and mortality, it is prudent to initiate empiric antibiotic therapy and admit all those with suspected meningitis to the hospital on droplet precautions, until pathogen is identified, and appropriate antibiotics have been given for 24 hours.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Meningitis is a serious disorder with high morbidity and mortality. The majority of patients with meningitis first present to the emergency department and a streamlined interprofessional approach is vital if one wants to lower the high morbidity. The triage nurse must be fully aware of the signs and symptoms of the illness and refer the patient immediately to the emergency department clinician. Other specialists who are usually involved in the care of these patients are neurologists, pediatricians, intensivists, infectious disease specialists, and pharmacists. If bacterial meningitis is suspected, prompt antibiotics should be started even in the absence of laboratory results. The pharmacist, preferably specializing in infectious diseases, should assist the clinical team in choosing the appropriate antibiotics based on the age of the patient and local sensitivities and correct dosing to ensure penetration into the central nervous system.

To prevent this infection, the education of the public is vital. All healthcare workers (nurses, physicians, and pharmacists) should educate patients and parents in regards to vaccine-preventable meningitis (H. influenzae type B, S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, Measles, and Varicella). Across the board, the incidence of meningitis has decreased with the implementation of generalized vaccination. Family members should be educated about the need for prophylaxis when there is a family member with Neisseria and H. influenzae type B meningitis. All contacts should be educated about the signs and symptoms of the infection and when to return to the emergency department.[18]