Continuing Education Activity

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is the most common cause of blindness prevalent in developed countries, particularly in people older than 60 years. It accounts for 8.7% of all types of blindness worldwide. This activity highlights the clinical features, symptoms, imaging characteristics of the disease, and the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the risk factors associated with age-related macular degeneration.

- Review the imaging features of the choroidal neovascular membrane.

- Outline the treatment options for the choroidal neovascular membrane.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) is the most common cause of blindness prevalent in developed countries, particularly in people older than 60 years. Macular degenerative changes involve the central part of the retina that is the fovea. The central vision is affected, resulting in difficulty in reading, driving, etc. It accounts for 8.7% of all types of blindness worldwide.[1]

Etiology

Several risk factors have been identified and associated with this disease.[2] Risk factors can be classified into a sociodemographic, lifestyle, cardiovascular, hormonal and reproductive, inflammatory, genetic, and ocular. Sociodemographic factors include age, gender, race, socioeconomic status. Various studies have demonstrated an increase in prevalence as well as the progression of ARMD with age.[3] Studies have found women to be at greater risk of ARMD. However, the association is not very consistent. Both early and late ARMD are known to be common among non-Hispanic whites when compared to blacks and Hispanics.[4] Socioeconomic factors like education, income, employment status, or marital status have no association with prevalence or stage of maculopathy.[5]

Smoking is an independent risk factor for ARMD.[6] Alcohol intake is not associated with the development of ARMD.[7] The role of other lifestyle factors like obesity and physical activity in the progression of ARMD is uncertain. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) documented that antioxidant and zinc supplementation decreases the risk of ARMD progression and vision loss.[8] A mild to moderate association between elevated blood pressure and ARMD has been described. Atherosclerotic lesions increase the risk of late ARMD.[9] No consistent relationship between cholesterol level and ARMD has been documented. Further studies are required to better define the mechanisms through which HDL mediates ARMD.[10] No significant relationship has been found between diabetes and ARMD.

Hormone replacement therapy or estrogen therapy in women after menopause has been found to have a potential protective effect.[11] Studies have suggested that inflammation plays a role in the pathogenesis of drusen and ARMD. Various complement-related genetic variants are associated with ARMD. These include Y402H in the CFH gene and other variants in factor B /complement component 2, complement component 3, and complement Factor I.[12]

Epidemiology

The disease is estimated to affect around 196 million people by 2020 and 288 million people by 2040.[1] Early AMD is more common in individuals of European ancestry than in Asians, whereas the prevalence of late AMD is the same between the two populations. In 2015, AMD was the fourth most common cause of blindness globally and the third most common cause for moderate to severe vision loss. This shows the increasing importance of AMD globally.[13]

Pathophysiology

The structures involved in the disease process are the photoreceptor cells in the outer retina, the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), Bruch’s membrane, and the capillary bed in the inner choroid (choriocapillaris).

- There is a loss of choriocapillaris in ARMD. Reduced diffusion of VEGF from RPE towards the choroid may be responsible for this loss. However, the occurrence of this damage independent of any other tissue is also a possibility.

- Bruch’s membrane thickening due to the accumulation of lipids has been long postulated in ARMD. This, in turn, results in reduced fluid movement from RPE towards the choroid. This reduced hydraulic conductivity causes fluid accumulation beneath the RPE and causes detachment of the RPE.

- Accumulation of lipofuscin in RPE, resulting in altered metabolism of the degraded photoreceptors occurs in this disease. This results in the accumulation of deposits (drusen) beneath the RPE.

- Photoreceptor loss, as well as shortening of outer segments of the photoreceptors, has also been documented in ARMD.

History and Physical

Age-related macular degeneration has been classified into two clinical forms dry or non-neovascular and wet or neovascular.

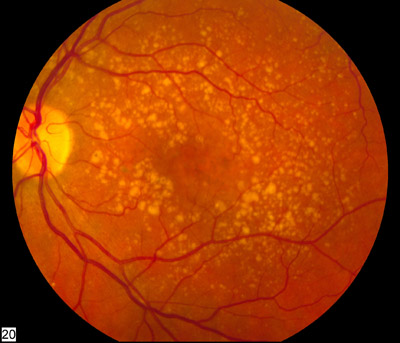

Vision loss is gradual if it occurs in the early or intermediate dry stage of ARMD. The examination of fundus reveals yellowish subretinal deposits or drusen and RPE hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentary changes. Drusen can be hard (definite boundaries) or soft (indistinct boundaries), or they may confluence into larger drusen and may evolve into drusenoid RPE detachments (PED). Atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium occurs in the advanced stage of the disease known as Geographic atrophy. Geographic atrophy on involving the center of the macula leads to significant visual loss.

The disease has been staged into four groups based on clinical examination of the macula:[14]

- Group 1 (no ARMD): no drusen or 5–15 small drusen (<63 microns in diameter) in the absence of any other stage of ARMD.

- Group 2 (early-stage ARMD): more than 15 small drusen or less than 20 medium-sized (63-124 micron in diameter) indistinct soft drusen or pigment abnormalities but not geographic atrophy.

- Group 3 (intermediate stage): the presence of at least one large druse ( >125 microns in diameter), or presence of numerous medium-sized drusen (approximately 20 or more drusen with indistinct boundaries and 65 or more drusen with distinct boundaries) or presence of non-central geographic atrophy i.e., atrophy not involving the fovea.

- Group 4 (advanced stage): central geographic atrophy that involves the fovea or presence of neovascular ARMD.

Geographic Atrophy

It is the advanced stage of dry ARMD. It is defined as a sharply delineated round or oval area of hypopigmentation or depigmentation or absence of the RPE. The choroidal vessels are more visible than in surrounding areas, and the atrophic patch must be at least 175 µm in diameter.[15] Geographic atrophy is known to enlarge over time, and it tends to be bilateral disease. Persons with unilateral GA are also at risk of developing neovascular or wet ARMD in the second eye.

Most commonly, drusen precede geographic atrophy. Larger drusen, confluent drusen, refractile deposits with hyperpigmentation have been documented to evolve into geographic atrophy. Geographic atrophy may also occur due to the collapse of drusenoid PED. The RPE and photoreceptors overlying the area of drusen progressively undergo degeneration.

Neovascular ARMD

Neovascular ARMD is characterized by a choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) and related features like PED, RPE rip, or disciform scarring. On fundus examination, CNV is seen as a grayish-green tissue below the retina along with fluid or blood in the intraretinal or subretinal plane.[16]

Degenerative changes in the Bruch's membrane weaken its integrity. Proangiogenic growth factors stimulate the growth of abnormal vascular networks from the choriocapillaris, which perforate the Bruch's membrane and disrupt the normal RPE-photoreceptor complex. A fibrovascular complex forms, which either lies completely below the RPE ( Type 1 CNVM) or breaches the RPE and lies in the subretinal plane (Type 2 CNVM). This complex can exude fluid or blood into the subretinal and intraretinal space. This fluid or blood can also accumulate beneath the RPE, causing pigment epithelium detachment. This complex progresses to a fibrotic disciform scar in the worst-case scenario.

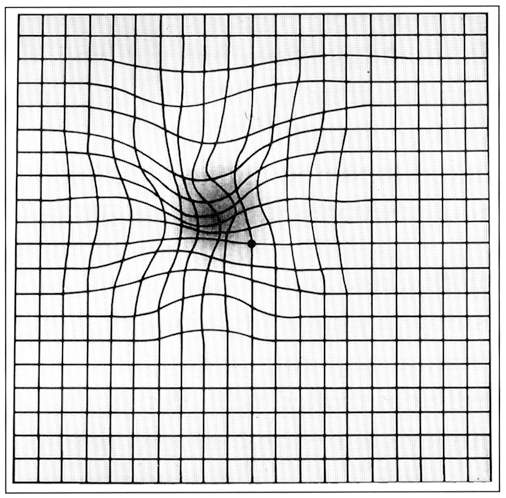

Symptoms noticed by the patients include blurring of vision and distortion, especially for near vision. Decreased vision, micropsia, metamorphopsia, or scotoma are other presenting complaints.

On fundus examination, pigment epithelial detachment is seen as a sharply demarcated dome-shaped elevation of the RPE. Overlying neurosensory detachment, lipid or blood, and sub RPE blood is a sign that a CNV is underlying the PED. Rarely, this blood can pass through the retina into the vitreous cavity, causing vitreous hemorrhage.

There are four types of PEDs. Serous, fibrovascular, drusenoid, and the fourth variant is hemorrhagic PED, which is characterized by the blood beneath the RPE.[17]

Serous PED is defined as an area of smooth, sharply demarcated dome-shaped RPE elevation. On fundus evaluation, a reddish halo of subretinal fluid can be seen. The presence of blood or pigment at the dependent part of the PED or a notched configuration of the PED raises the suspicion of the presence of an underlying CNVM. The notch is the area where the CNVM adheres to the RPE and causes it to detach from the Bruch's membrane. Fibrovascular PED, in contrast to serous PED, is an area of irregular elevation of the RPE. Its name is derived from the underlying vascular and fibrous components. Drusenoid PED is a detachment of the RPE caused due to the confluence of soft drusens.

Evaluation

Imaging of Dry ARMD

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA): Drusen constituents can be hydrophobic or hydrophilic. Fluorescein dye being hydrophilic stains the hydrophilic drusen. Hyperfluorescence is noted in the late stage of angiography. Geographic atrophy is seen as well defined hyperfluorescent area due to window defect. The underlying choroidal fluorescence is seen due to the absence of RPE.

Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA): The hard drusen become hyperfluorescent 2 to 3 minutes after dye administration, and this persists through the middle and late phases. Soft drusen are either hypofluorescent throughout the angiogram with a thin hyperfluorescent rim, or they remain isofluorescent.

Autofluorescence: This provides an evaluation of RPE activity. It helps define the area of geographic atrophy. The area of atrophy shows hypofluorescence due to the loss of RPE, whereas the border is slightly hyperfluorescent. Fluorescence at the border of the atrophy is a marker for the progression of geographic atrophy. Autofluorescence is more sensitive in picking up progression in comparison to clinical examination.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): Drusen are seen as a nodular elevation of RPE. Drusen area and volume can be measured on optical coherence tomography (OCT) and used as a prognostic marker. Area of geographic atrophy is seen as a patch with the absent external limiting membrane, inner/outer segment junctions of photoreceptor, and the RPE and Bruch's membrane complex. Choroidal signal enhancement or choroidal hyperreflectivity is noted in the area of geographic atrophy.

Imaging of neovascular ARMD

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA)

Fluorescein angiography is useful in identifying the type of PED. On fluorescein angiography, serous PED shows uniform filling with bright fluorescence that persists till the late phase. The lesion shows well-demarcated borders with no leakage. The intense hyperfluorescence is thought to be due to the rapid diffusion of the fluorescein molecules across the permeable Bruch's membrane and pooling in the sub-RPE space.

Fibrovascular PED on FFA reveals an area of stippled or granular hyperfluorescence, which is seen as early as within 1-2 minutes of fluorescein injection. These areas intensify or reveal leakage or staining in the later phases. Leakage is because of fluid accumulation in the subretinal space overlying the PED, and staining is due to entrapment of dye within the fibrous tissue.

Drusenoid PED has scalloped borders and an irregular surface. FFA shows gradual staining of the sub-RPE with no leakage. Pigment deposits, when present, are seen as hypofluorescent foci.

A hemorrhagic detachment of the RPE on FFA will block the choroidal fluorescence because of the mound-like collection of blood beneath the RPE. Hence it appears hypofluorescent.

Choroidal neovascular membranes have been defined on angiography as classic and occult. Earlier the inclusion criteria of various treatment trials required the knowledge of the composition of the CNVM. However, with the advent of intravitreal injections and spectral-domain OCT, indications for baseline FFA have reduced significantly.

Classic CNVM is identified as lesions that hyperfluoresce in the early phase with an increase in intensity and leakage beyond the boundaries of the hyperfluorescent area through mid and late phase frames. Subretinal fluid, when present, can be seen as the pooling of fluorescein dye overlying the CNVM.

Occult CNV refers to two hyperfluorescent patterns on fluorescein angiography: fibrovascular pigment epithelial detachment (FVPED), and late leakage of an undetermined source (LLUS). Fibrovascular pigment epithelium detachment appears as an irregular elevation of the RPE with stippled hyperfluorescent dots overlying it. The boundaries may or may not show leakage in the late-phase frames depending on whether the fluorescein stains the fibrous tissue or pools in the subretinal space overlying the FVPED. The second pattern, late leakage of an undetermined source, is defined as leakage in the late phase with no identifiable CNV in the early or mid-phase of the angiogram to account for the area of leakage in the late phase.

Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA)

It is known for better visualization of the choroidal vessels. It is a more sensitive tool in comparison to FFA for identifying underlying CNVM associated with serous, drusenoid, or hemorrhagic PED. Serous PED on ICGA is a hypofluorescent lesion that remains hypofluorescent in all phases of the angiography. Hyperfluorescent spot in the hypoflourescent lesion, usually seen in the area of notching, is due to an underlying CNVM. Drusenoid PED is hypofluorescent to isofluorescent on ICGA, and CNVM, if present, is seen as hyperfluorescent component.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): It is useful in defining the type of choroidal neovascular membrane (hyperreflective lesion) based on its location beneath the RPE (type 1) or above the RPE (type 2). It enables follow up of patients on intravitreal therapy as it helps monitor the activity of CNVM by accounting for the resolution or recurrence of intraretinal or subretinal fluid and change in the height of the PED. The fluid is hyporeflective on OCT.

The four variants of PED can be differentiated on OCT. Serous PED is seen as a dome-shaped elevation of hyperreflective RPE over hyperreflective Bruch's membrane. The PED lumen is hyporefflective because of its serous content. In contrast, fibrovascular PED lumen has both hyperreflective and hyporeflective component due to the presence of a fibrovascular component beneath the RPE. Similarly, drusenoid PED is hyperreflective because of drusen. Hemorrhagic PED shows hyperreflectivity just beneath the RPE with backshadowing such that the Bruch's membrane or the choroidal vessels underlying the PED is not visible. This is because of the presence of blood, which prevents the rays from traveling further.

Various prognostic markers have been identified on OCT like outer retinal tubulations (ORT) and hyperreflective dots.[18][19] ORT is seen as a round structure with hyperreflective walls and hyporeflective lumen. It is present in the outer retina. It can mimic subretinal fluid, so it should be carefully looked for as the former does not respond to intravitreal therapy. Its presence indicates a poor improvement in visual acuity.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for Dry ARMD

Dry ARMD cases require regular follow up to identify early signs of progression to an advanced stage or neovascular ARMD. Early ARMD in both eyes requires no intervention. There is no evidence to suggest that using a dietary supplement of antioxidants and minerals, reduces the risk of progression to advanced ARMD or even to intermediate ARMD among individuals with early ARMD. However, they should be educated to undergo annual reassessments to check for progression to intermediate ARMD. Individuals with intermediate ARMD or advanced ARMD in at least one eye should be started on the dietary supplement, as suggested by AREDS.[20][21] Individuals with advanced ARMD in both eyes may consider this supplement if the individual has a visual acuity of 20/100 in at least one eye.

The formulation suggested by AREDS 1 is a daily dose of 500 mg vitamin C, 400 international units of vitamin E, 15 mg beta carotene, and a daily dose of 80 mg zinc oxide with 2 mg cupric oxide added to reduce the risk of copper-deficiency anemia. This formulation was modified by AREDS 2 to a daily dose of 500 mg vitamin C, 400 international units of vitamin E, 80 mg zinc oxide, 2 mg of cupric oxide, 10 mg of lutein, 2 mg of zeaxanthin and 1 g of omega -3 fatty acids. Beta carotene was removed as it increased the risk of lung cancer, especially in smokers. Macular pigments lutein and zeaxanthin provided an additional reduction of risk of progression of the disease.

Treatment for Neovascular ARMD

Laser Photocoagulation

Lesion sufficiently peripheral to the fovea that presents minimal risk of iatrogenic damage is the one that can undergo laser treatment. Macular photocoagulation studies revealed poor outcomes and high recurrence rates after thermal laser treatment, hence used rarely nowadays.[22]

Photodynamic Therapy

PDT was introduced in 2000 as less destructive phototherapy for treating CNV. It involves the application of light of a specific wavelength to the CNVM after administering drug verteporfin intravenously. The light incites a localized photochemical reaction in the targeted area, resulting in CNV thrombosis. The progression of CNVM is slowed, but the visual prognosis is poor. Also, PDT is known to upregulate VEGF. PDT is sparingly used nowadays except for cases of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy.[23][24]

Antiangiogenic Therapy

Both growth-promoting, as well as growth-inhibiting factors, contribute to angiogenesis. Activators of angiogenesis include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor α and β, and angiopoietin 1 and 2. Inhibitors include thrombospondin, angiostatin, endostatin, and pigment epithelium-derived factor.

VEGF has been found to play a causal role in CNVM in ARMD. It induces vascular permeability, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis and inhibits apoptosis of endothelial cells. VEGF 165 isoform is the most dominant form in ARMD. Many intravitreal anti-VEGF therapies have been approved as agents who reduce the growth of CNVM as well as help in the resolution of edema.

The first one to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was pegaptanib in 2004. It is an RNA oligonucleotide ligand, also known as an aptamer that binds VEGF 165.[25] Ranibizumab, Bevacizumab, and Aflibercept have supplanted pegaptanib since then.

Ranibizumab is a recombinant humanized antibody fragment (Fab) that binds VEGF. It binds to all isoforms of VEGF. Studies like MARINA, ANCHOR, PIER, and EXCITE have proved that ranibizumab administered in monthly doses causes not only reduced loss of ETDRS letters in treated eyes but also improves visual acuity in treated eyes compared to control eyes.[26][27]

Other than monthly treatment regimens, patients can opt for treatment ‘as per need’ or ‘treat and extend’ regimens. In the former regimen, after monthly injections that achieve a dry macula, treatment is reinitiated based on the recurrence of fluid. This reduces the number of injections for the patients. Treat and Extend regimen involves monthly injection till the macula is dry, then after that, the treatment interval is prolonged by two weeks till the macula remains dry. Similarly, the interval is reduced by two weeks when recurrence is noted. This, in turn, reduces the number of visits to the hospital.[28]

Aflibercept, also known as the VEGF trap, is a protein that acts as a VEGF receptor decoy. It has a combination of ligand binding elements of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, which is fused to the constant region (Fc) of immunoglobulin IgG.

It binds both VEGF and placental growth factor and has good retinal penetration. VIEW 1 and 2 studies have documented that aflibercept is non-inferior to ranibizumab in terms of gain in the number of ETDRS letters while measuring visual acuity at the end of the treatment period. A higher dose of aflibercept administered every two months instead of monthly was also seen to be as effective as a monthly dose of ranibizumab.[29]

Bevacizumab is a full-length monoclonal antibody against VEGF, which was approved by FDA for metastatic colorectal carcinoma. It is being used as an ‘off label’ treatment for ARMD. The major advantage provided is the burden of cost per injection for the patient compared to ranibizumab and aflibercept. CATT trial compared the efficacy of bevacizumab to ranibizumab and documented that bevacizumab was found to be non-inferior to ranibizumab.[30][31][30]

The advent of intravitreal injections has reduced the need for other treatments like laser or surgery in patients with ARMD. However, Intravitreal injections do have side effects of their own. Minor complication like subconjunctival hemorrhage is common. In rare cases, major events like vitreous hemorrhage, endophthalmitis, and retinal detachment may occur. There is conflicting evidence regarding systemic adverse events like myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accidents due to these agents. The penetration of these drugs into the retina is known to be hampered by the presence of an epiretinal membrane. Separation of the posterior hyaloid by surgery helps increase the permeability of these drugs in such cases.

Surgery is required in a few cases of ARMD, where patients present with submacular hemorrhage. Intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator with pneumatic displacement is helpful in such cases.[32] Submacular surgery involving the removal of CNVM and macular translocation surgeries have been abandoned nowadays.[33][34] A significant proportion of patients improve with the use of intravitreal agents. However, a noteworthy number of patients do progress to blindness as well. In these cases, rehabilitation with low vision aids should be considered and is found to be very effective.

Differential Diagnosis

Reticular pseudodrusen should be differentiated from drusen. The former are deposits above the RPE that is in the subretinal plane.

Fundus features of dry ARMD should also be differentiated from adult vitelliform macular dystrophy and retinal drug toxicity. Fundus in adult vitelliform dystrophy reveals yellowish subretinal deposits, whereas RPE pigmentary changes due to drugs like hydroxychloroquine, deferoxamine, and cisplatin can mimic the seen in Dry ARMD.

Neovascular AMD should be differentiated from retinal angiomatous proliferation and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV). Retinal angiomatous proliferation is also known as type 3 CNVM, where the neovascularization begins within the retina and then progresses towards the RPE and choroid. On FFA, early phases reveal a retinal vessel dipping perpendicularly into the CNVM component, indicating the retinochoroidal anastomosis.

Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy can be differentiated on fundus examination by the presence of orangish nodules along with subretinal hemorrhage or fluid. OCT shows large choroidal vessels, also known as pachyvessels, in these cases. The choroid is thickened, unlike ARMD, where the choroid is thin. ICGA shows polyps that are diagnostic of PCV.

Pearls and Other Issues

Here are some important points to remember:

- ARMD is the leading cause of blindness in the elderly age group.

- Regular follow up in cases of early ARMD can help in the timely recognition of signs of progression and facilitate initiation of treatment.

- With the advent of SD-OCT, the follow up of these patients has improved significantly. Various prognostic markers that have been identified on SD-OCT are useful clinically in decision making regarding treatment and patient education and counseling regarding the visual prognosis.

- Intravitreal anti-VEGF injections have largely replaced all the other treatment modalities. The visual acuity achieved at the end of the treatment period is much better than that achieved with the laser. Patients' quality of life has improved. With treat and extent regimen being used widely, the burden of the cost of injections, as well as the number of visits to the hospital, have reduced significantly.

- Low vision aids are very helpful in rehabilitating the patients who progress to blindness despite treatment.

- The disease is a bilateral process that makes the patient dependent and affects the quality of life.

- The cost of intravitreal injections is a burden for the patient.

- Regular follow up in cases of monthly dosing also increases the number of visits to the hospital.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

ARMD is one of the leading causes of blindness in the elderly population. Interprofessional communication and coordination are important in screening for this disease. People above the age of 50 years should undergo an eye evaluation by an ophthalmologist to rule out the presence of ARMD. Physicians should recommend an eye examination for their elderly patients. This is important, especially in recognizing patients with early ARMD, as these patients are often asymptomatic.

The aim is to educate the patient regarding the need for regular follow up and the benefits of timely intervention. Similarly, physicians may refer patients with poor vision to an ophthalmologist as these patients can benefit from low vision aids. Patients with ARMD and poor vision can be given wrist bands which mention the condition of the patient so that people around them can be careful and prevent them from falling and from other such accidents. ARMD can be managed appropriately if recognized timely and treated sincerely. Intravitreal injections are the standard of care for these patients. The cause-effect relationship of systemic side effects and these drugs is not well established.[35] Therefore, the risk-benefit ratio is favorable.