Introduction

The Greek word for eyelid is “blepharon,” from which is derived the prefix "belpharo," which has been in use since antiquity. The Greek for an eyelash is “blepharida” which is not used in medicine today. The Latin for eyelid is “palpebra” and that for eyelash is “cilium” a word only in use since the early 18 century.

Eyelashes and eyebrows are important anatomical structures which are central not only in the face but central to all perceived human interactions. Eyebrow movement conveys emotions (sad, happy, angry, surprise, pensive, etc.) and eyebrows protect the eyes by relaxing the “curtain rods” that they effectively are when tired, thereby relaxing the upper eyelid skin and contributing to lid closure and eye protection. Eyebrow hair direction serves to protect the eyes from particulate matter and sweat.

Eyelashes and eyebrows have always been an essential part of facial beauty. They have been plucked, accentuated and modified in innumerable ways to enhance the beauty of the face and eyes in particular in many cultures. The Egyptians and the Indians have used materials like kohl to enhance brows and lashes for centuries. The emphasis of the eyes manifests in the modern world through the use of mascara, eyeliner, and eyeshadow. Curlers are used to exaggerate the natural curve of lashes. Although long lashes are prized in most cultures, certain cultures (the Hazda, the last of the hunter-gatherer tribes of Tanzania) trim their lashes.

Comparative Anatomy

Mammals have eyelashes; some, like the camel, have profoundly long lashes, long used to accentuate features in cartoons. Cows have long straight lashes which are medially oriented. A description of “cow lash deformity” is used when seen as a complication of blepharoplasty, often affecting the lateral third of the upper eyelid.[1] Other large mammals like horses also have similar long, relatively straight lashes.

The eyelash viper is said by some in South America to wink after striking its victim. The “lashes” are not lashes, but modified scales above the eyes. And, of course, snakes cannot wink as they have no eyelids!

Structure and Function

Surface Anatomy

In humans, there are 75 to 80 lasheson the lower eyelid., and the upper eyelid has 90 to 160 lashes. Lash length is variable from individual to individual: they do not grow beyond a certain length (usually less than 12 mm) and then fall off by themselves. Current thinking is that lash length is limited because the growth rate and the anagen phase are shorter than scalp hair. Eyebrow hairs may be longer, especially with age (Denis Healey brows). Eyelashes generally do not need trimming unless there is excessive growth (trichomegaly). Ms. You Jianxia of Shangai holds the world record for the longest eyelashes in 2018: her lashes measure 12.40 cm! After lash removal by pulling, it takes about eight weeks to grow back. Eyelash hair is not affected by puberty.

Lashes curve in all ethnicities. The curvature has been shown to occur because of asymmetric cell types along the concave and convex sides of the bulb. Similarly, this asymmetry is also present in curly hair. The curve of the lashes is more in Caucasians compared to Asians. Lashes have lift-up and curl-up angles which have been measured photographically producing a phototrichogram.

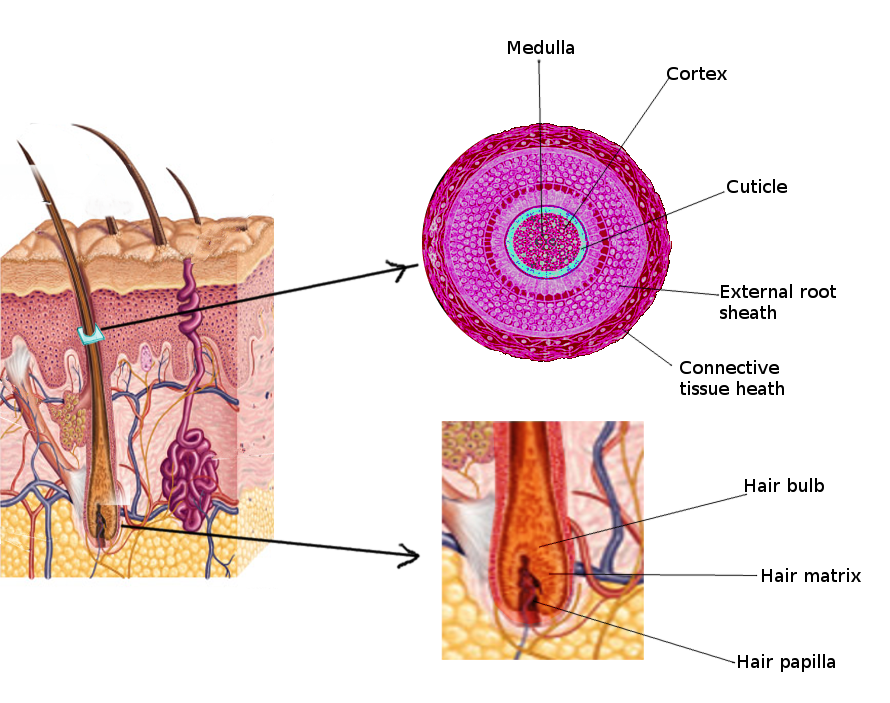

Cross-sectional Anatomy

Each lash has a hair shaft that extends outside the skin, a root which is under the skin and a bulb which is the enlarged terminal portion. The inferior portion of the bulb is in direct contact with the dermal papilla, which has a vascular supply, allowing interactions which lead to follicle cycling. The lash has an inner medulla composed of cells, a surrounding medulla or cortex, which is stiffer and gives the lash strength and rigidity, and the outer concentric layer which is the cuticle. The cuticle, which is impermeable, protects the inner part of the lash.

The outermost layer, the cuticle is seven to ten layers thick and made up of transparent overlapping scales.

The next layer, the cortex is the thickest portion of the lash and is composed of keratin.; this layer contains melanin.

The eyelash follicle (follis, Latin for bag): the term follicle refers to the complex that is responsible for hair growth and is composed of the dermal papilla which is connective tissue with a capillary loop, the germinal hair matrix around the papilla and the lash root or bulb. The germinal layer has dividing cells which give rise to the hair, and the bulb is where the process of keratinization begins. The hair follicle embeds in the dermis of the eyelid (which has two layers, epidermis and dermis, as opposed to the scalp which has an epidermis, dermis and a hypodermis). Eyelash follicles are 2.4 mm deep in the upper lid and 1.4 mm in the lower lid. There are more active lash follicles in the upper lid compared to the lower lid (41% vs. 15%).[2]

The hair on the body has arrector pili muscles which straighten the hair in the cold or response to a strong emotion (fear, excitement) resulting in what is commonly termed “goose-bumps” or “goose pimples” because of the resemblance to plucked goose skin. The lash follicle has no arrector pili muscles. Therefore, lashes do not change position in these circumstances.

Lash follicles connect to two types of secretory glands:

- Zeiss glands are holocrine glands which liberate the complete cell content, sebum, which acts as a lubricant and has antimicrobial properties.

- Glands of Moll are only found in eyelids and are apocrine, which means the cells fragment, thereby producing secretions which are thought to have antimicrobial properties.

Eyelash Pigmentation

Melanocytes synthesize melanin by melanogenesis. Lashes seem to become gray or white much later than scalp hair. Continued expression of enzymes such as tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP-2), which influences melanocytes, is thought to be the reason. Scalp hair not only suffers depletion of melanocytes by apoptosis and oxidative stress but also reduced expression of enzymes like TRP-2. There has not been adequate study on the changes in lash pigmentation with age in different races.

Aerodynamics Around Lashes

Eyelashes have an essential role in the protection of the eye. Aerodynamic studies have demonstrated that the ideal lash should be one-third the width of the eye. Besides protecting the cornea from particulate matter, it appears that the aerodynamic flow of air because of the curve and density of lashes plays a role in corneal protection. The exact ways in which evaporation may be increased or decreased by lashes is unknown. Although in vitro studies have been attempted, there have been no in vivo studies performed on human lashes and corneas.

Life Cycle of Lashes

Lashes grow at 0.12 to 0.14 mm per day (as compared to scalp hair which grows at 0.2 to 1.1 mm per day). The three phases of lash growth in the eyelash growth cycle are:

The growth phase when the root of the hair is dividing lengthening the shaft (anagen) which varies from four to ten weeks

The degradation phase (catagen) during which the lash converts to a club hair as the hair is cut off from the blood supply 15 days

The resting phase (telogen) which causes shedding of the hair, lasts four to nine months

Half the eyelashes are in an anagen phase: periocular hair has the lowest anagen to telogen ratio. After the telogen phase, the lash falls out, and the cycle begins anew with the anagen phase. The whole lash cycle is from four to eleven months.

The stages of the life cycle of lashes compared to the eyebrows and the scalp is as follows:

- Eyebrows:

- Anagen phase, 4 to 7 months

- Catagen phase, 3 to 4 weeks

- Telogen phase, around 9 months

- Scalp: genetically determined and varies from person to person

- Anagen phase, 2 to 8 years (can be longer)

- Catagen phase, 2 to 3 weeks

- Telogen phase, about 3 months

Lash microflora: Propionibacterium, Streptophyta, Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and enhydrobacter are common bacteria found on lashes. In the presence of blepharitis, Staphylococcus, Streptophyta, Corynebacterium, and Enhydrobacter increase. Ineterestingly, Propionibacteriumis often decreased in the presence of blepharitis.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis are natural parasites which increase in numbers with age. By the age of 70 years, almost 100% of people will have these parasites. D. folliculorum live in eyebrows, scalp hair, ears and eyelashes, whilst D. brevis is found in the sebaceous oil glands in the face and in Meibomian glands. Inflammation of eyelids is caused when the parasite dies (bursts), releasing its contents which is inflammatory. Cylindrical debris is found around the lashes and is pathognomonic of demodex.

Embryology

Condensation of mesenchymal cells first occurs at week nine forming eyelash follicles and their appendages. At this stage, the tarsal plate and the orbicularis oculi also develop together with evidence of blood vessels. By week 12, multiple eyelash follicles can be seen under the skin and by week 14, eyelashes together with sweat glands and sebaceous glands appear.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superior and inferior marginal arteries from the ophthalmic artery supply the upper and lower eyelids, respectively. The upper eyelid marginal arterial arcade is near the follicles of the eyelashes, anterior to the tarsal plate and 2 mm superior to the lid margin. The superior arcade lies between the Muller muscle and the levator aponeurosis. The lower eyelid may have one or two arcades, but the arcades are further from the lid margin, at the inferior border of the tarsal plate. The internal carotid artery supplies the eyelids via the ophthalmic artery and the external carotid artery through the angular and temporal arteries. Therefore, there is extensive collateral supply from these two systems.

Venous drainage is pretarsal and posttarsal: the pretarsal venous drainage is into the angular vein medially and the superficial temporal vein laterally. The posttarsal venous drainage is into the superior and inferior ophthalmic vein and the pterygoid plexus and anterior facial vein.

Lymphatic drainage from the medial eyelids is to the submandibular lymph nodes; that from the lateral eyelids is to the preauricular nodes.

Nerves

The eyelid margin is among the most sensitive parts of the human body as evidenced by the pain experienced during the administration of a local anesthetic removal of eyelid margin lesions. Free nerve endings envelop the eyelashes. Addition, lanceolate and circular Ruffini nerve endings (also called corpuscles) are present, which provide touch, pressure, vibration, heat, and mechanoreception. Besides eyelashes, the anterior eyelid cutaneous surface has fine vellus hairs: these possess similar innervation. Furthermore, Meissner corpuscles (sensitivity to light touch) are also found, especially on the occlusal surface of the eyelids. This profusion of intricate innervation makes the lashes and the eyelid margins especially sensitive.[4] The sensitivity of eyelashes is comparable to the sensitivity of a cat or mouse whiskers with similar function.

Muscles

Eyelashes lack the arrector pili muscle found elsewhere, so the lashes do not change position in the presence of cold, emotion, etc.

Physiologic Variants

Age-related Travel in Lashes

Studies of lashes in different age groups have shown that there is a generalized reduction in the thickness, pigmentation, and length of lashes with age but there are few proper longitudinal studies. Thibault improved our understanding of lashes and the change over time by studying defined lashes over nine months, measuring the length each week.[5][6][7]

Canities is the natural gradual graying of hair shafts because of tyrosine production decrease in the hair bulb.

Surgical Considerations

Knowledge of the structure and distribution of eyelashes, as well as of the depth of the lashes in the upper and lower eyelids is vital when performing surgery that involves the eyelid margin.

Clinical Significance

The anatomy of the eyelash differs from hair elsewhere in the body in many respects. Knowledge of these differences is essential when addressing eyelid, eyelid margin, and eyelash problems. There are unique eyelash problems which are not seen in hair elsewhere on the body because of the particular anatomical differences and the relationship of the growth, curvature, and location to the cornea.