Continuing Education Activity

Petechiae are pinpoint non-blanching spots that measure less than 2 mm in size and affect the skin and mucous membranes. Petechial rashes are common and can be a significant cause for concern for parents and the interprofessional team. Petechial rashes result from areas of hemorrhage into the dermis. The primary pathophysiological causes of petechiae are thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, disorders of coagulation, and loss of vascular integrity. Though there are many causes of a petechial rash in a child, invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) caused by Neisseria meningitidis is one of the most concerning reasons. A child with a fever and a petechial rash requires an urgent and comprehensive assessment. This activity reviews the causes of petechiae and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with petechiae.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of petechiae.

- Describe the evaluation of petechiae.

- Summarize the treatment options available for petechiae.

- Review interprofessional team strategies for optimizing care coordination and communication to advance the evaluation and management of petechiae to improve outcomes.

Introduction

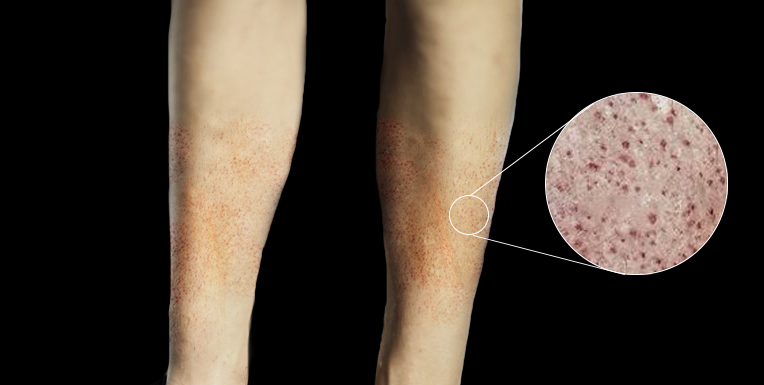

Petechiae are pinpoint non-blanching spots that measure less than 2 mm in size, which affects the skin and mucous membranes. A non-blanching spot is one that does not disappear after applying brief pressure to the area. Purpura is a non-blanching spot that measures greater than 2 mm. Petechial rashes are a common presentation to the pediatric emergency department (PED). Non-blanching rashes can be a great cause for concern for parents and physicians alike. Therefore, careful assessment and evaluation are necessary to formulate a sensible management plan.[1][2][3]

Etiology

There are many causes of a petechial rash in a child to be considered. Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) caused by Neisseria meningitidis, is the priority in the differential diagnosis to consider on the initial presentation. Consequently, a child with a fever and a petechial rash requires urgent and comprehensive assessment. Multiple studies have shown that the rate of IMD has reduced following the introduction of meningococcal vaccines into childhood immunization schedules and that the low prevalence of IMD suggests that most children presenting with a petechial rash have less serious pathologies. However, given its associated morbidity and mortality, it should remain at the forefront of the clinician's mind when assessing the child with pyrexia and petechiae.[4][5]

Causes can classify into the following categories:

Infective

- Viral: Enterovirus, parvovirus B19, dengue

- Bacterial: Meningococcal, scarlet fever, infective endocarditis

- Rickettsial: Rocky Mountain Spotted fever

- Congenital: TORCH

Trauma

- Accidental injury

- Non-accidental injury

- Increased pressure following bouts of coughing, vomiting or straining

Hematological and Malignant

- Leukemia

- Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)

- Thrombocytopenia with absent radius (TAR) syndrome

- Fanconi anemia

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS)

- Splenomegaly

- Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (NAIT)

Vasculitis and Inflammatory Conditions

- Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Connective Tissue Disorder

Congenital

- Wiscott-Aldrich syndrome

- Glanzmann thrombasthenia

- Bernard-Soulier syndrome

Other

- Drug reaction

- Vitamin K deficiency

- Chronic liver disease

Epidemiology

One study reported that 2.5% of presentations to the pediatric emergency department were patients with a petechial rash.[6]

Pathophysiology

Petechial rashes result from areas of hemorrhage into the dermis. Derangements in the normal hemostasis can result in petechiae along with a variety of other clinical findings. The primary pathophysiological causes of petechiae and purpura are thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, disorders of coagulation, and loss of vascular integrity. Some clinical pictures result in petechial lesions from a combination of these mechanisms.[7][8]

History and Physical

A detailed history and physical examination are paramount for every child presenting with petechiae. Key features in the history include the time of onset, anatomical pattern and a detailed chronological account of any other symptoms, e.g., fever, coughing, vomiting, any recent URTI or gastroenteritis, and any sick contacts. A rapidly spreading rash is more concerning for IMD in an unwell child with a fever. A recent viral infection (URTI or gastroenteritis) is common in ITP, HSP, and HUS. Petechiae confined to above the nipple line are associated with bouts of vomiting or coughing. It is also important to ask about any bleeding from mucosal surfaces such as gingival bleeding, epistaxis, melena, among others. As always, the clinician should confirm vaccination status.

On examination, a complete set of observations and neurological status requires monitoring. A full systemic examination should be completed, including cardiac, respiratory, abdominal, otorhinolaryngological, and neurological (if concerns of IMD). The skin should undergo thorough examination from head to toe, and the pattern of rash requires clear documentation. Demarcating areas of petechiae with a skin marker can help monitor the progression of the rash in clinical practice.

The age of the child can be useful in reaching the most likely diagnosis, for example, a neonate with petechiae could have a NAIT or a TORCH infection, and HSP is more common in the 2 to 5 year age range.

Patterns of concerning symptoms and signs presenting with petechiae include but are not limited to:

- Pyrexia, tachycardia, reduced level of consciousness and rapidly spreading petechiae: IMD

- Pallor, bruising, weight loss, lymphadenopathy: Malignancy

- Hypertension: Renal disease associated with HUS, HSP or SLE

- Unusual patterns of petechiae with bruising, an inconsistent history or signs of injury or neglect: NAI

Evaluation

Investigations to diagnose the cause of a petechial rash depend on the clinical presentation and can differ from one PED to another. Adhering to the local protocol is advised. In general, investigations will depend on the location of petechiae, associated pyrexia, or clinical suspicion for any of the concerning patterns of signs and symptoms for particular illnesses such as IMD, HSP and HUS. A healthy child with scattered petechiae of obvious causation, e.g., known trauma or petechiae confined to above the nipple line, may not require any investigations, and a period of observation in the PED may be sufficient. Petechia and fever is often concerning for IMD and poses as a clinical dilemma, though IMD accounted for only 1.4% of cases with fever and petechiae in a recent large-scale prospective UK cohort study. [9] Many clinical guidelines pre-date the introduction of meningococcal B and C vaccination (for example, the NICE clinical guidelines) and a cautious approach can lead to many children undergoing painful procedures and receiving unnecessary antibiotics in populations with high vaccination rates.

Investigations may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC) to check platelet number, a raised or decreased white cell count or decreased hemoglobin.

- If concerns about IMD or other infection: C-reactive protein, blood culture and procalcitonin if available, along with blood gas, renal, liver and coagulation profiles.

- Renal, liver and coagulation profiles may also be necessary in other cases (DIC, IMD, HSP, HUS). A prolonged prothrombin time can indicate factor deficiencies, vitamin K deficiency, DIC, liver, or renal disease.

- Urine dipstick and microscopy are useful when renal causes are part of the differential (HSP, HUS, SLE), to check for proteinuria in particular.

- Further tests may be later requested when narrowed down to a more specific diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

Many patients attending the PED with petechial rashes will not require any specific treatment. If a child remains well after a period of observation, with no spreading of the rash, a normal platelet count and no physical signs or signs of infection on blood tests (raised white cell count and inflammatory markers), they may be discharged home. If IMD is likely, urgent intravenous antibiotics as per local guidelines should be administered, with close observations after admission to the ward or intensive care unit. Some patients may receive a dose of antibiotics pre-hospital if high clinical suspicion of IMD is present. If there are specific diagnoses, for example, HSP or ITP, and the child remains well, they may be discharged with an appointment to return to the appropriate outpatient department and condition-specific education. Other conditions will require admission and treatment, for example, urgent referral to oncology inpatient services for a patient with pancytopenia and probable malignant diagnosis.[10][11]

Differential Diagnosis

Pearls and Other Issues

Recognizing the full range of possible diagnoses for a child presenting with petechiae is essential for any clinician working in the PED. Public health sepsis campaigns have increased recognition of petechiae, therefore, allaying parents' fears and concerns is a crucial role, in addition to educating them on red flag signs that should prompt return to the PED. Senior clinicians should be involved in decision-making to avoid both unnecessary tests or antibiotics and to avoid missing cases of IMD.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are many causes of petechiae, and condition management is optimally by an interprofessional team that includes clinicians, specialists as indicated, hematology nurses, and pharmacists. The key is to determine the primary cause. Most patients with a benign cause or drug-induced petechiae have a good outcome when discontinuing the offending agent. However, when petechiae are due to heparin, paradoxical thrombosis can occur.[12] Cross-disciplinary communication and collaboration of the entire interprofessional healthcare team will guide these cases to the optimal outcome. [Level 5]