Introduction

The sinoatrial nodal artery is a branch of the main coronary arteries, or its derivatives, which supplies blood to the heart's pacemaker, the sinoatrial node. This artery can also supply blood to the crista terminalis and the free walls of both the left and right atrium.

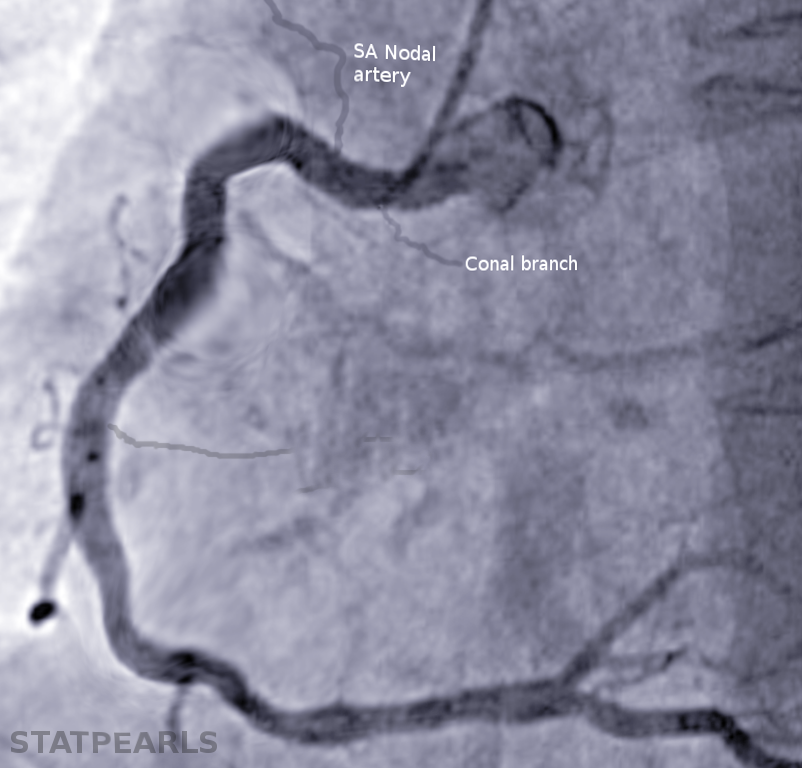

The sinoatrial nodal artery most commonly originates from the right coronary artery (68% of patients) and less commonly from the left coronary artery and left circumflex artery (24.7% of patients).[1] The sinoatrial node is a vital component of normal heart function as it provides the initial electrical signal for atrial contraction and sends conductivity signals to the atrioventricular node. The sinoatrial nodal artery is a crucial component in supplying this specialized myocardial tissue with adequate oxygen and nutrients necessary for healthy activity.

Structure and Function

Structural Overview

The sinoatrial nodal artery can be derived from the right coronary artery (most common), the left coronary artery, or the left circumflex artery. If the sinoatrial nodal artery originates from the right coronary artery, it is typically more proximal and located only 1.2 cm on average from the origination of the right coronary artery at the ostia. If the sinoatrial nodal artery originates from the left circumflex, it can be either distally or proximally located. The diameter of the artery can range from 1.7 to 2.2 mm, depending on the artery from which it originates. The sinoatrial artery typically takes a retrocaval approach to reach the sinoatrial nodal tissue, but in 30% of cases, the sinoatrial nodal branches have been noted to form a ring around the superior vena cava.[2]

Histology

The sinoatrial nodal artery consists of three layers - adventitia, media, and intima. The outermost layer is the adventitia, consisting of collagen and elastic tissue, providing the artery with flexibility and strength. Furthermore, the adventitia contains the artery’s blood supply, also known as the vasa vasorum, nerves, and lymphatic vessels. Lying inside the adventitia is the media layer of the artery which contains multiple layers of smooth muscle. This smooth muscle allows for vasoconstriction or vasodilation of the artery to allow the tissue to meet its metabolic requirements.

Additionally, the medial layer contains connective tissue consisting of elastic fibers, collagen, and proteoglycans, which provide for the further structural integrity of the artery. The intimal layer lines the inside of the artery and consists of endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and a subendothelial layer with associated connective tissue. The endothelial cells are aligned longitudinally, allowing the artery to have a selective barrier to diffusion for the other layers. The endothelial cells also produce prostacyclin, PGI, which acts as an antithrombotic agent, and the von Willebrand factor, which acts as a prothrombotic agent. Also, the endothelial cells release growth factors, lipoprotein receptors, and some inflammatory mediators.

Function

The sinoatrial nodal artery functions to provide oxygen and nutrients predominantly to the sinoatrial nodal tissue; however, the artery has been known to supply collateral branches to the atrium and auricles of the same side as its origin and, in some cases, to the opposite side. Oxygen is a crucial component to allow for the normal function of tissue, and without it, viability would not be possible. As the artery approaches the capillary bed of the tissue, it thins out, and the endothelial cells allow the selective permeability of nutrients necessary for viability.[3][4]

These nutrients consist of electrolytes, vitamins, and glucose essential to meet the metabolic demands of the tissue. Any alteration of this delicate balance could be devastating to the tissue and lead to life-threatening complications.

Embryology

The embryological derivation of the coronary arteries has been a long-studied topic, and the results remained ambiguous for decades until a recent study. This research concluded that coronary vessels sprout from the sinus venous predominantly.[5] The endothelial cells of the sinus venous grow onto the developing heart, where they dedifferentiate to form the coronary plexus.[6]

From this point, they further develop into arteries, arterioles, capillary beds, and the venous system. The study also noted a secondary source in the endocardiac tissue where blood islands form. These blood islands join with the coronary plexus at the site of the interventricular septum. Local signals released from developing tissue schedule this dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of endothelial tissue from the sinus venous. These signals also guide the pathway of the coronary vessels and the tissue into which it will redifferentiate. Eventually, the coronary vascular system is in place and joins with the aorta at the coronary ostium.[7]

Muscles

The sinoatrial nodal artery consists of vasculature smooth muscle cells. Smooth muscle cells are present within the media of the artery and group into electrically coupled aggregates. The smooth muscle cells respond to various signals for vasodilation and vasoconstriction to allow the artery to meet the metabolic requirements of the tissue to which it provides blood.

Furthermore, smooth muscle cells of the artery are essential in adaptive wall remodeling. Remodeling occurs in response to intraluminal injuries such as catheters, stents, or downstream ligation; this is done mainly through microribonucleic acids, which signal the migration and differentiation of smooth muscle cells to repair the injured tissue.

Finally, When atherosclerosis is present in the endothelial lining of the artery, the intimal smooth muscle cells initiate a pro-inflammatory response, leading to the conversion of smooth muscle cells to foam cells (which are macrophage-like cells located in a hyperlipidemic environment).[8] They then migrate and start engulfing the lipids, which ultimately leads to the formation of plaques within the arterial lining. These plaques are the pathogenesis of coronary vascular disease and can lead to many coronary complications in the future.[9]

Clinical Significance

The sinoatrial node is an aggregation of specialized myocardial tissue located in the right atrium of the heart, which spontaneously releases electrical signals to the atrial tissue and atrioventricular node, signaling the heart to contract. The node's more colloquial name is the "pacemaker" of the heart. Like any living tissue, it has a metabolic requirement to function appropriately. As stated above, this tissue receives vascular supply via the sinoatrial nodal artery, and if there is any disruption to this blood supply, devastating consequences can result, such as arrhythmias.[10]

Coronary artery disease ranks as one of the leading causes of death in the United States, predominately due to disruptions to the vasculature supplying the heart. Risk factors of coronary artery disease are numerous, but the most significant are smoking, male gender, family history of coronary artery disease, increased LDL, decreased HDL, and hypertension, which can lead to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in the arterial lining and progressively limit the blood supply passing through the artery or lead to thrombotic events.

If the artery is unable to transport enough blood to meet the tissue's metabolic requirements, the tissue can become non-viable leading to tissue necrosis. Furthermore, like any other artery, the sinoatrial nodal artery can be prone to aneurysms. Though rare, these occur mainly in proximal or midportions of the artery. They are usually secondary to atherosclerotic lesions and are treatable with surgical approaches.[11]