Introduction

The rectum is the most distal portion of the large intestine, bound by the sigmoid colon proximally and converging into the anal canal distally. This segment of the intestine derives its name from Latin intestinum rectum meaning “straight intestine,” describing its course compared to the tortuous appearance of the rest of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Coursing within the pelvis, the rectum is the most posterior visceral organ in the pelvic cavity with differing anatomical relationships to male and female structures.

Structure and Function

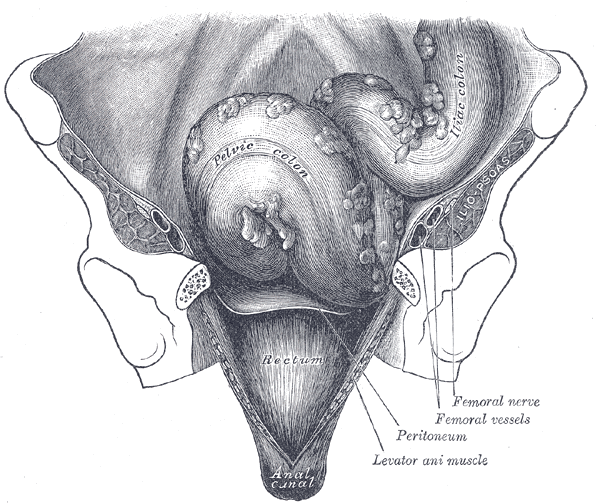

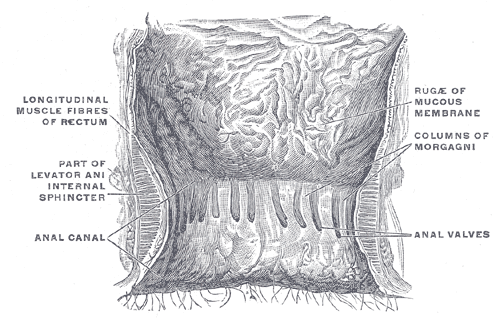

The rectum starts at the level of S3 around the sacral promontory as a continuation of the sigmoid colon. This portion of the GI tract is differentiated from the colon by the coalescence of taenia coli where the muscular bands spread to form the outer longitudinal muscle layer of the rectum.[1] The rectum measures between 12 to 15 cm in length from the rectosigmoid junction to the dentate line in the anal canal. Its course is marked by two anterior-posterior flexures, with the rectum first following the concavity of the sacrum at the sacral flexure and later coursing with an anterior convexity at the anorectal flexure. There are also three lateral flexures, made by submucosal folds in the lumen called valves of Houston, often two on the left and one on the right.[1] The final portion of the rectum is the ampulla, which is an expanded segment that rests on the pelvic diaphragm. The rectum transitions to the anal canal at the level of the levator ani muscle.

The peritoneum covers the upper third of the rectum anteriorly and laterally, but the middle third is only covered anteriorly. The lower third is not covered by the peritoneum but starting at this level, the fascia propria envelops this segment of the rectum. This fascia is more pronounced laterally, forming the lateral rectal stalks. The rectum is attached posteriorly to the presacral fascia at the level of S4 via the Waldeyer fascia.[2]

The peritoneal reflection is variable between individuals but is generally six to eight cm from the anal verge. In men, the reflection of the peritoneum to the posterior bladder forms the rectovesical pouch. In women, the reflection is from the rectum to the posterior cervix forming the rectouterine pouch, also known as the pouch of Douglas.

The rectal wall consists of five layers, starting from the lumen: the mucosa, deep mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa that is covered by the peritoneum. An inner circular and outer longitudinal muscular layer comprise the muscularis propria. The inner circular layer thickens at the anorectal junction, forming the internal anal sphincter while the outer layer continues as the longitudinal layer of the anal sphincter.[2]

The rectum functions primarily as a temporary reservoir for feces storage. It also plays an integral role in controlling defecation as well as maintaining continence.[2][2]

Embryology

The rectum derives from the hindgut, which also gives rise to the segment of the GI tract from the transverse colon down to the dentate line.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), the most distal branch of the abdominal aorta before its bifurcation, ends as the superior rectal (hemorrhoidal) arteries. This artery supplies the rectum and upper third of the anal canal. The rectum receives additional vascular contributions from the middle rectal artery, which is a branch of the internal iliac artery, supplying the distal rectum and proximal anal canal. The inferior rectal artery comes off the internal pudendal artery, which is also a branch of the internal iliac artery. Collaterals between the inferior and superior hemorrhoidal arteries exist at the level of the dentate line, making the incidence of rectal ischemia low.[2][4][2]

Venous drainage of the rectum accompanies the arterial supply. Blood drains from the rectum in either the systemic or portal system. The majority of blood from the rectum drains into the superior rectal vein that drains into the portal system through the inferior mesenteric vein. The distal portion of the rectum and anal canal has drainage through the middle and inferior rectal veins into the internal iliac veins via the pudendal vein.[1]

The lymphatic drainage of the rectum follows the arterial supply as well. The rectum drains into the superior rectal lymphatics to the retroperitoneal inferior mesenteric lymph nodes. Additionally, the middle and inferior hemorrhoidal vessels have lymphatic drainage into the internal iliac nodes. Below the dentate line in the anal canal, the lymph drains to the inguinal nodes.[1]

Nerves

The rectum has autonomic innervation from sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. The sympathetic innervation is from the lumbar splanchnic nerves originating from L1 to L2. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers follow the pathway of the IMA to innervate the left colon and rectum. They join to form the preaortic and superior hypogastric plexuses. The nerve fibers from these plexuses enter the rectum laterally to provide sympathetic innervation to the lower rectum.[2]

Parasympathetic supply originates from the sacral region and courses anteriorly to join the sympathetic fibers forming the pelvic plexus. Postganglionic parasympathetic and sympathetic fibers then distribute to the rectum through the inferior mesenteric plexus.[2][5][2]

The sensation of rectal distension is carried by the parasympathetic system to S2, S3, and S4.[6]

Muscles

The rectum is supported by the pelvic floor muscles, which also aid in the process of defecation and continence. The levator ani muscles comprise much of the pelvic floor; these are the iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis muscle.[7]

Surgical Considerations

The anatomical location of rectal cancer is critical as it dictates the surgical approach. Rectal tumors located in the upper and middle third are manageable with procedures sparing the anal sphincter, such as low anterior resection surgery.[8] Tumors located in the lower rectum, within 5 cm of the anal verge, however, may require an abdominal perineal resection in which rectal cancer along with normal rectum and anal sphincter is resected through the perineum, resulting in a permanent colostomy.[8]

During surgical dissection, nerves are at risk of injury leading to sexual dysfunction in men with symptoms of erectile or ejaculatory dysfunction.[8] There are several potential sites for nerve injury during rectum resection. The first potential site of injury is at the origin of the IMA. The purely sympathetic hypogastric plexus lies in this area; therefore, an injury could occur during ligation of the IMA pedicle causing retrograde ejaculation.

In the dissection of the posterior plane of the rectum, rectal dissection is outside the fascia propria. Nerves sit adjacent to this plane of dissection and are easily injured if the surgeon does not take the correct dissection plane. Injury at this location results in purely sympathetic damage as the parasympathetic fibers have not yet joined.[8]

In the anterior dissection of the rectum, the fascia between the rectum and the prostate alongside the seminal vesicles is divided; this is a very narrow space that is difficult to access, resulting in potential damage to mostly parasympathetic fibers causing impotence as the anterior dissection goes deeper into the pelvis.[8]

Clinical Significance

The anatomical position of the rectum is vital in the digital rectal exam in men. The prostate sits anterior to the wall of the rectum, which allows for manual palpation to assess for nodules, shape, and size of the prostate in carcinoma screening. In women, the cervix, uterus, and vagina sit anteriorly to the rectum, and a digital rectal exam is often in conjunction with the manual pelvic exam. Posterior vaginal wall weakening could result in a rectocele where the rectum herniates into the vagina.[9][10][9]