Continuing Education Activity

Lymphogranuloma venereum is an ulcerative sexually transmitted infection of the genital area caused by Chlamydia trachomatis that is transmittable by vaginal, oral or anal sex. This activity describes the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of Lymphogranuloma venereum and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of lymphogranuloma venereum.

- Outline the typical presentation of a patient with lymphogranuloma venereum.

- Review treatment considerations for patients with lymphogranuloma venereum.

- Describe the importance of collaboration and communication amongst interprofessional team members to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by lymphogranuloma venereum.

Introduction

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is an ulcerative disease of the genital area.[1] Its cause is the gram-negative bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis, especially serovars L1, L2, and L3.[2] It is an uncommon, sexually transmitted infection. It is transmittable by vaginal, oral or anal sex. There are increasing numbers of reports in men who have sex with men.[3][4]

Characteristically, lymphogranuloma venereum has three stages of infection [1]:

- Primary stage characterized by the development of painless genital ulcer or papules.

- Secondary stage with the development of unilateral or bilateral tender inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy (also called buboes).

- Late stage with strictures, fibrosis, and fistulae of the anogenital area.

Etiology

The causative agent is Chlamydia trachomatis, serovars L1, L2, L3.[5] Chlamydia is a ubiquitous ovoid or obligate intracellular bacteria.

Epidemiology

Lymphogranuloma venereum is common in the tropical and subtropical regions around the world. It is rare in the United States.[6] Lymphogranuloma venereum may occur at any age; however, the highest incidence of LGV is in the sexually active population between 15 and 40 years. Lymphogranuloma venereum probably affects both sexes equally although it is more commonly reported in men because early manifestations of LGV are more apparent in men.[7] It is endemic to men who have sex with men. There is a significant association between HIV-infected patients and LGV.[8] Men typically present with the acute form of the disease whereas women often present when they develop complications from later stages of the disease.[7]

Pathophysiology

Lymphogranuloma venereum primarily affects the lymphatic system. Chlamydia trachomatis serovars extend from the primary infection site to the regional lymph nodes and cause a lymphoproliferative reaction, facilitated by binding of Chlamydia trachomatis to the epithelial cells. Binding occurs via heparin sulfate receptors.[9]

Histopathology

Lymph nodes:

Tiny necrotic foci infiltrated by neutrophils represent the earliest microscopic change in an affected node. These enlarge and coalesce to form the stellate abscess that represents the most characteristic feature of this disease. In later stages, epithelioid cells scattered Langhans giant cells, and fibroblasts are seen to line the abscess walls. Confluence of these abscesses is common, and cutaneous sinus tracts may develop. Nodules with dense fibrous walls surrounding amorphous material represent the healing stage.[1]

Rectal biopsies:

Histopathologic examination of rectal biopsies in patients with LGV proctitis usually reveals severe inflammatory changes, and these have been misattributed to inflammatory bowel disease in recent years. Histopathologists should consider LGV in the differential diagnosis when reporting on inflammatory rectal biopsy specimens as a relevant risk behavior might not be provided in the clinical history accompanying the specimen.[1]

History and Physical

Evaluation should involve a thorough history including a sexual history.

Characteristically lymphogranuloma venereum has three stages [10]:

Primary Stage

- Begins in 3 to 12 days after exposure or sometimes it may be longer up to 30 days.

- The patient characteristically develops a painless genital ulcer or papules which are about 1 to 6 mm in size. Sores can also be present in the mouth or throat. An inflammatory reaction can occur at the site of inoculation.

- This stage often goes unnoticed due to the location of the lesions and as the lesions are usually small and there are no associated symptoms.

- The lesions resolve or heal spontaneously after few days.

Secondary Stage

- The secondary stage presents with the development of unilateral or bilateral tender inguinal and/or femoral lymphadenopathy (also called buboes), which occurs two to six weeks after the primary stage; this is called the inguinal syndrome.

- An anorectal syndrome also presents which is characterized by proctitis or proctocolitis-like symptoms. Pain during urination, rectal bleeding, pain during passing stools, abdominal pain, anal pain, tenesmus. Generalized symptoms like body aches, headache, and fever can occur during this stage. This syndrome usually occurs when the transmission is via the anal route.[11]

- An oral syndrome can occur in people get LGV through the oral route. Cervical lymphadenopathy can occur.

- There are also reports of systemic complications like pneumonia and hepatitis.[12]

Late Sequelae

Usually, occur when the disease is left untreated.

- Necrosis and rupture of the lymph nodes

- Anogenital fibrosis, and strictures

- Anal fistulae

- Elephantiasis of the genital organs can also occur in some cases

Evaluation

Diagnosis is by clinical suspicion. Other causes of genital ulceration and inguinal adenopathy should be excluded.[13]

The basis for a definitive diagnosis of LGV is on serology tests (complement fixation or micro-immunofluorescence) or identification of Chlamydia trachomatis in genital, rectal and lymph node specimens (by culture, nucleic acid amplification test or direct immunofluorescence).[14]

Men who have sex with men who have signs and symptoms of proctocolitis should receive testing for LGV. In these patients testing of rectal specimens with nucleic acid amplification test is the preferred approach.[15][14]

HIV testing should be a consideration in patients with a sexually transmitted infection.

Treatment / Management

The recommended treatment regimen is doxycycline 100 mg orally twice a day given for 21 days.[16]

An alternate regimen is erythromycin 500 mg orally four times a day given for 21 days.

Azithromycin 1 gm orally once weekly for 3 weeks is also an effective alternative regimen.[2]

All patients who are suspected to have LGV (either genito-ulcerative disease with lymphadenopathy or proctocolitis) should be empirically treated for LGV before an official diagnosis is certain.

Pregnant patients can have treatment with erythromycin. Doxycycline and other tetracyclines should be avoided in pregnancy due to the risk of disruption of bone and teeth development.

Patients who have fluctuant or pus-filled buboes can benefit from aspiration of the node, which provides symptomatic relief, although incision and drainage of the nodes are not recommended as it can delay the healing process.[17]

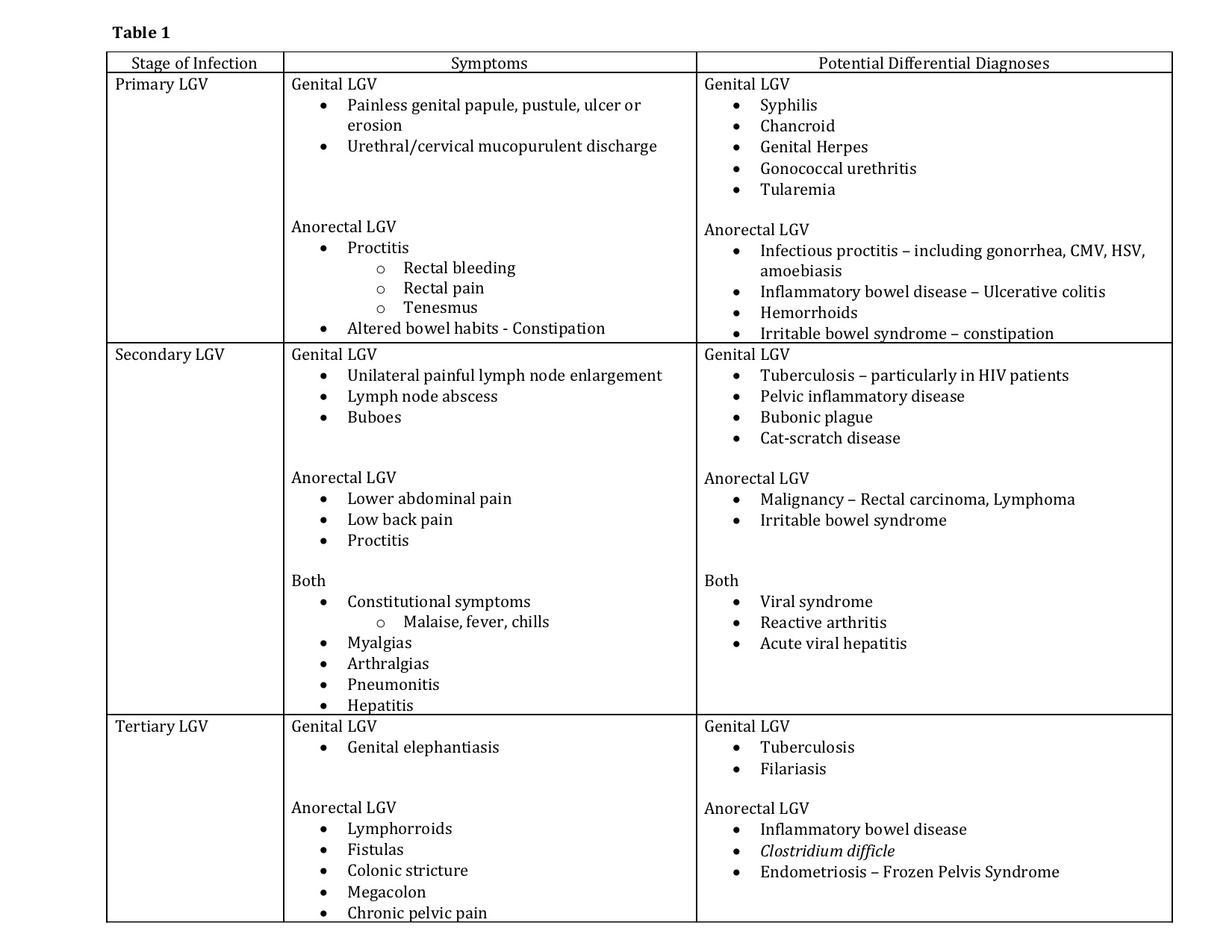

Differential Diagnosis

Sexually transmitted infections are the first to consider in the differential diagnosis of LGV.

The exclusion of diseases which cause genital ulceration and inguinal adenopathy including herpes simplex, syphilis, chancroid, herpes, and granuloma inguinale will help narrow the diagnosis.

HIV and lymphoma can also cause generalized lymphadenopathy.

Dermatological conditions and trauma which can cause genital ulcerations should also be in the differential diagnosis.

Prognosis

Prognosis is fair if recognized and treated early.

Complications

Complications usually occur when the disease is left untreated — necrosis and rupture of the lymph nodes, anogenital fibrosis, and strictures, anal fistulae. Elephantiasis of the genital organs can also occur in some cases. Systemic complications like pneumonia and hepatitis also have been reported.[18]

Consultations

In difficult to diagnose and treat cases and infectious disease consultation may be warranted.

Surgical consultation is needed for tertiary or late-stage disease if complications like fistulas or strictures cause damage to the anorectal area.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should receive education regarding the signs and symptoms of early recognition of LGV. Having LGV can increase a patients risk of contracting other sexually transmitted infections like HIV, hepatitis, syphilis, chancroid, gonorrhea, etc. Patients should learn about the need to use condoms or other protective measures while engaging in sexual activity. Sexual partners of patients who tested positive or probably positive should also be tested, and treatment initiated if necessary. Men who have sex with men should recognize that LGV is prevalent in these populations and should know the signs and symptoms of LGV.

Pearls and Other Issues

Management of Sexual Partners of LGV Patients:

All exposed partners of LGV probable or confirmed patients in the last 60 days should receive testing and empiric treatment with a chlamydial regimen (doxycycline 100mg PO BID for 7 days or 1gm azithromycin one-time dose). Appropriate testing should be done based on the route of transmission and can include either cervical, urethral or rectal specimens. If testing for chlamydia and/or LGV comes back positive, then treatment should be continued to complete a 21-day course. If testing is negative for chlamydia or LGV, then treatment should cease after 7 days.

A diagnosis of LGV should be taken into consideration by gastroenterologists and histologists in patients presenting with proctitis or inguinal lymphadenopathy, particularly in men who have sex with men.[19]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Treatment of LGV affected patients and the recognition of potentially exposed partners requires a coordinated effort from the physicians and nursing staff. Physicians and nurses should educate the patients on the early recognition of signs and symptoms of LGV and other STDs and encourage to seek treatment early to improve outcomes and prevent and complications. Pharmacists should recognize the different medications used for the treatment of LGV and their complications and educate the patients including the risks and benefits of usage of these medications in pregnancy and lactation. an interprofessional approach will provide the best long-term results for these patients. [Level V]