Continuing Education Activity

Retinitis is an inflammation of the retina, which can cause permanent vision loss. Numerous microbes can cause retinitis. These pathogens can affect patients differently depending on characteristics like age, location, and immune status. Important noninfectious causes like Behcet disease also can cause retinitis as its primary manifestation in the eye. Retinitis may present alone or with varying choroidal involvement as retinochoroiditis or chorioretinitis, depending upon the site of primary involvement. This activity will discuss the more common causes of retinitis and the role of an interprofessional team.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of retinitis.

- Describe the clinical findings of various etiologies of retinitis.

- Outline treatment options available for retinitis.

- Summarize the complications and prognosis of retinitis and the role of the unprofessional team in identifying the etiology and guiding appropriate management at the earliest in order to save vision and improve outcomes.

Introduction

Retinitis is an inflammation of the retina, which can cause permanent vision loss. A number of microbes can cause retinitis, including Toxoplasma, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes zoster, Herpes simplex, and Candida. Retinitis may also be seen in cat-scratch disease from Bartonella species, lyme disease from Borrelia burgdorferi, syphilis caused by Treponema pallidum, or tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium species. These pathogens can affect patients differently depending on characteristics like age, location, and immune status. Important non-infectious causes like Behcet disease also can cause retinitis as its primary manifestation in the eye. Retinitis may present alone or with varying choroidal involvement as retinochoroiditis or chorioretinitis, depending upon the site of primary involvement. The more common causes of retinitis will be discussed in detail.

Etiology

Infective Causes

Protozoa

Toxoplasma gondii is a ubiquitous intracellular parasitic protozoan commonly causing posterior uveitis. Humans and other mammals act as intermediate hosts, while cats are the definitive hosts for T. gondii. T. gondii exists in 3 forms, including sporozoites, which are contained within oocysts, tachyzoites, which are the active replicating forms responsible for systemic dissemination in intermediate hosts and bradyzoites which are the dormant forms residng in tissue cysts.

Viruses

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is an enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the Herpes family. Ocular CMV infection may manifest as anterior uveitis, corneal endotheliitis, or as the potentially blinding chorioretinitis.[1] The retinitis is typically seen in immunocompromised individuals.

- Acute retinal necrosis (ARN) syndrome is most often caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), other less common causes include Herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1 or HSV-2), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) or rarely Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The patients can be immunocompetent or immunocompromised.

- Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) is a clinical variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy caused by the varicella-zoster virus and seen in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).[2]

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a fatal neurodegenerative disease caused by a genetically altered form of the measles virus. It is commonly seen in children and young adults.[3] Ocular findings can be seen in up to 50% of SSPE cases ranging from neuro-ophthalmic to retinal features. Visual symptoms may also precede neurological symptoms. The classic lesion is focal necrotizing macular retinitis; however, vitritis is not a feature, unlike Toxoplasma retinitis. There may be associated retinal hemorrhages, edema, and retinal detachment. Vision loss may be due to chorioretinitis, cortical blindness, or optic disc changes, including papillitis, papilledema, and optic atrophy.

- Dengue can cause retinitis and foveolitis.

- Chikungunya infection can have varied anterior and posterior segment manifestations with iridocyclitis and retinitis being the most common.[4] The disease usually has an excellent prognosis with a self-limiting course.

Bacteria[5]

- Syphilis caused by the bacterium, Treponema pallidum, is a leading cause of posterior uveitis. Ocular manifestations can occur in all stages of the disease though they are more prevalent in secondary and tertiary syphilis.

- Cat scratch disease caused by Bartonella henselae, a gram-negative hemotrophic bacillus, is acquired when humans come in contact with flea feces or via trauma from a cat scratch or cat bite.

- Rocky Mountain Spotted fever is a zoonosis caused by obligate intracellular small Gram-negative bacteria R. rickettsii transmitted to humans by the bite of contaminated ticks. Common ocular findings are retinitis (seen in 30% of patients with acute RMSF), retinal vascular involvement, and optic disc changes.[6]

- Lyme disease (Borreliosis) is a vector-borne zoonosis caused by the bite of Ixodid tick infected by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. Retinitis is a rare presentation seen in the late disseminated stage (>3 months) of the disease.[7]

- Endogenous endophthalmitis or metastatic endophthalmitis accounts for 2% to 8% of all cases of endophthalmitis.[8] Risk factors include medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, liver disease, cardiac disease, malignancy, in-dwelling catheters, and intravenous drug abuse (IVDU).

Fungus

- Candida and Aspergillus are the most common causes of fungal endogenous endophthalmitis. Immunocompromised patients are at particular risk of developing the disease.

- Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS) occurs in immunocompetent individuals and is recognized by the presence of peripapillary atrophy and multiple atrophic chorioretinal scars without vitreous or aqueous humor inflammation.

Helminth

- Toxocariasis caused by the nematode Toxocara canis is a rare but important cause of posterior uveitis in infants and young children. Ocular toxocariasis can present as posterior pole or peripheral granuloma, with few patients developing dense vitritis mimicking endophthalmitis.

- Diffuse unilateral subacute neuro retinitis (DUSN) is an ocular infectious disease caused by a worm whose etiology has not been completely understood that can lead to visual impairment and blindness.

Post-fever retinitis is the term used to describe the various retinal manifestations seen after a systemic febrile illness caused by either bacteria, viruses, or protozoa. It manifests approximately 2 to 4 weeks after onset of fever in the immunocompetent and responds favorably to steroids, suggesting a possible immunological basis for this condition.[9] Posterior segment manifestations include focal and multifocal patches of retinitis, possible optic nerve involvement, serous detachment at the macula, macular edema, and localized involvement of the retinal vessel in the form of vessel beading, tortuosity, and perivascular sheathing.

Noninfective Causes

- Behcet disease is an autoimmune, chronic inflammatory disease that can affect multiple organ systems with the primary histologic feature being occlusive vasculitis.

- Sarcoidosis

- Other causes including

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Churg–Strauss syndrome

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Birdshot retinochoroiditis

Epidemiology

CMV retinitis is primarily a disease of immunocompromised hosts, occurring in neonates, persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) from the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), or renal and solid organ transplant recipients as a result of long term immunosuppressive therapy. It is the most common opportunistic ocular infection in patients with AIDS typically occurring when CD4 T lymphocyte counts fall below 50 cells/microliter.[10] The current prevalence of CMV retinitis has reduced by 80% after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) from 20% to 40% in the pre-HAART era. The survival after diagnosis has also increased to one year after antiretroviral therapy.[11]

Recent reports indicate that acquired toxoplasma infections account for a larger portion of ocular involvement than congenital toxoplasmosis, contrary to the popular belief that ocular toxoplasmosis in adults is secondary to the recurrence of the congenitally acquired infection.[12] Toxoplasma retinitis is the most common infective posterior uveitis in immunocompetent individuals. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis accounts for 30% to 55% of posterior uveitis in high T. gondii endemic regions of the U.S. and European nations.[13]

ARN is a syndrome of acute panuveitis that can affect immunocompetent or immunosuppressed patients of either gender at any age.

Behcet disease is more common in men than in women and typically affects young adults.

The prevalence of Behcet disease varies geographically, with the disease being more common in countries along the old Silk route, including China, Japan, Mideast, and the Mediterranean basin.[14]

Rocky Mountain spotted fever caused by R. rickettsii, is endemic in parts of North, Central, and South America.[6]

Lyme disease is endemic in North America and Europe.[7]

POHS is usually seen in patients who live in areas endemic to H. capsulatum, which include states that contain the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.[15]

Human infection in toxocariasis is acquired by contact with cats or dogs which are likely to carry the infection. Although it can affect adults, the primarily affected age group is young children and infants.

Pathophysiology

In necrotizing viral retinitis, including herpetic retinopathy and CMV retinitis, the virus infects retinal cells and causes necrosis from virally induced cytolysis and vascular occlusion.

Behcet disease is an auto-immune inflammatory vasculitis involving both arteries and veins of all sizes. Histopathologically, non-granulomatous inflammation is seen. Increased local expression of proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-1-beta (IL-1beta), changes in polymorphonuclear cells, and endothelial dysfunction play a role in the pathogenesis of Behcet disease-associated vasculitis.[16][17]

Post-fever retinitis may be the result of direct invasion of the pathogen or by indirect invasion mediated through immune mechanisms.

Toxoplasma gondii has been proposed to reach ocular tissues via blood and yield a focus of inflammation. The primary lesion is retinitis, and choroid may be involved secondarily. Host immune responses induce the conversion of tachyzoites to bradyzoites and their encystment, which may remain inactive in the scar for a long time. However, there may be reactivation of cyst at the border of these old scars when the cyst ruptures with the release of organisms into the surrounding retina. However, new lesions are sometimes found at distant locations from old scars. [12]

Metastatic endophthalmitis occurs due to the spread of blood-borne organisms. The microbes enter the internal ocular spaces through the blood-ocular barrier in patients with risk factors.

The defective measles virus in SSPE directly affects the optic nerve, retina, and choroid resulting in optic neuritis, retinitis, and chorioretinitis, respectively.[18]

History and Physical

Fresh retinitis lesions appear as whitish or slightly yellow lesions in the posterior pole or periphery depending upon the aetiological agent. In fresh lesions, the margin is usually blurred or fuzzy, and there is retinal edema leading to the opaqueness of the retina and obscuration of the details of the choroid. It may be associated with vitreous inflammation, vasculitis, vascular occlusions, or hemorrhage. OCT (optical coherence tomography) shows hyperreflectivity of inner or all retinal layers (according to the level of involvement) with or without overlying vitreous cells. FFA (fundus fluorescein angiogram) reveals early hypofluorescence with late hyperfluorescence of the lesions with leakage of dye into surrounding tissues. As they heal, they either heal with pigmentation or lead to retinal thinning and atrophy.

CMV infection probably reaches the eye through hematogenous spread. Three types of clinical appearance may be seen clinically in CMV retinitis:

- Wedge-shaped areas of a perivascular fluffy white lesion with many scattered hemorrhages (brush-fire)[19]

- A more granular-appearing lesion that has few associated hemorrhages and often has a central area of clearing, with the atrophic retina and stippled retinal pigment epithelium (granular type)

- Rarely, retinal vasculitis with perivascular sheathing (an atypical manifestation with a clinical appearance similar to frosted branch angiitis)

The disease usually spreads centrifugally along the retinal vessels; the border of active retinitis is irregular, and small white satellite lesions are very characteristic.[20] Minimal, if any, vitritis is noted with clear media as a result of the immunosuppressed state of the patients. Vitritis is less than expected for the degree of retinal necrosis. Fine keratic precipitates (KPs) may be present, although most patients have no anterior chamber reaction.

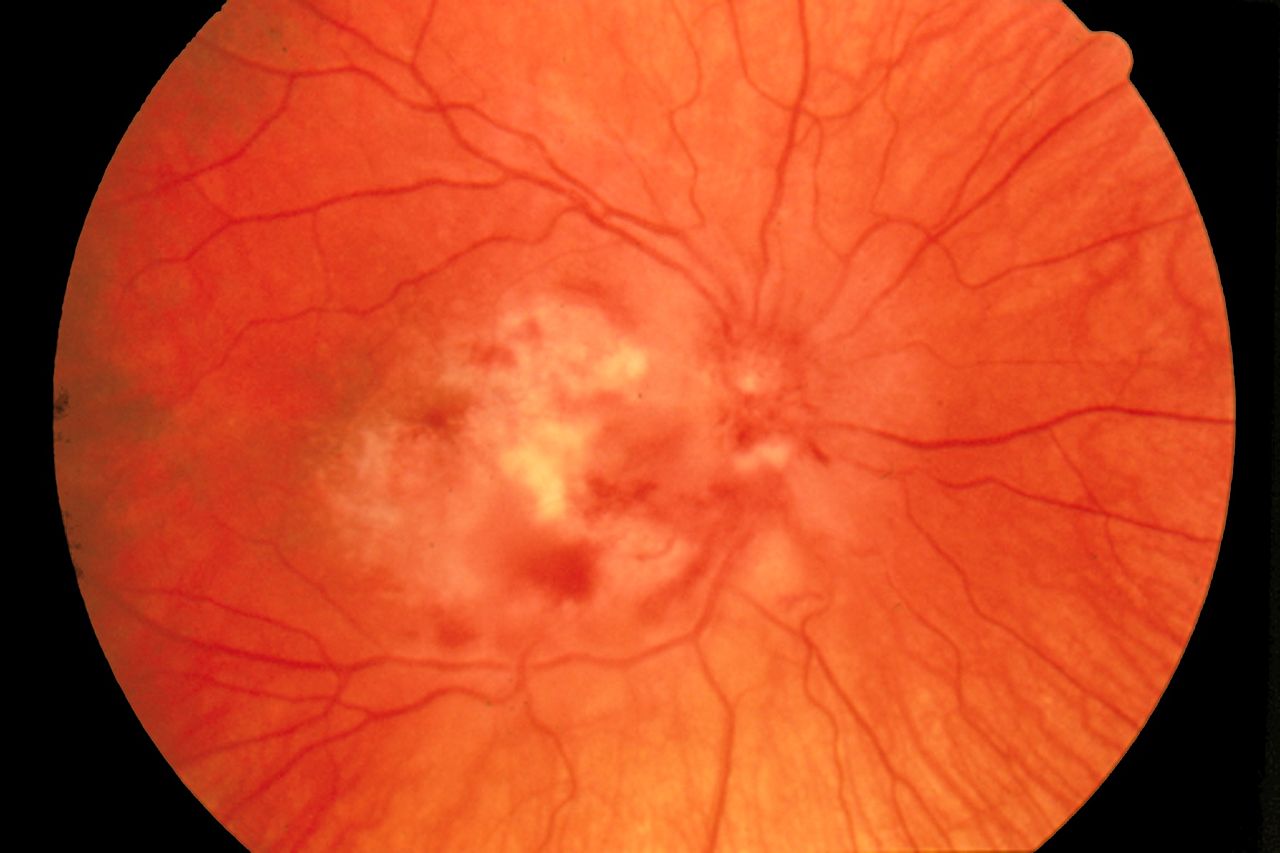

Clinically, Toxoplasma presents as focal areas of retinitis with overlying localized or diffuse vitritis classically described as "headlight in fog" appearance. There may be adjacent pigmented retinochoroidal scar with a variable degree of vitreous inflammation. Recurrent lesions tend to occur as satellite lesions next to old atrophic lesions, sites of previous toxoplasma infection. Anterior uveitis may be either granulomatous or nongranulomatous, with severity ranging from mild to severe. Perivasculitis may be present near the active lesion with periarteriolar collections of cells seen as distinct Kyrieleis plaques. Such plaques have also been reported in ARN, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, Behcet disease, CMV retinitis, leptospirosis, rickettsial disease, and syphilis.[21][22][23] Toxoplasmosis may have a different presentation in immunocompromised- vitritis may be less, there may be multiple or atypical/large retinitis lesions, a pigmented scar may be absent, and neuroimaging should be done to rule out the involvement of the central nervous system (CNS).

PORT (Punctate Outer Retinal Toxoplasmosis) is a subset of ocular toxoplasmosis involving outer retinal layers and associated with little or no overlying vitreous reaction. Grey-white lesions at the level of the deep retina and retinal pigment epithelium are seen, which resolve as white, punctate tiny dots. It is important to identify this variant as the treatment of toxoplasmosis might improve outcomes in this disease.[24]

ARN is characterized by prominent anterior segment inflammation that may be granulomatous, or non-granulomatous. The disease starts in the periphery with full-thickness discrete necrotizing lesions with scalloped borders. Typically, hemorrhages are less prominent, if present. The posterior pole is involved later in the course of the disease. Inflammation of the arterioles can lead to occlusive arteritis, causing more rapid retinal necrosis. Other associated features include vitritis/media haze, optic disc edema, raised intraocular pressure, and scleritis. Although the disease starts unilaterally in the majority, fellow eye involvement may occur as early as 1 to 6 weeks.[25]

An extreme variant of necrotizing herpetic retinopathy in immunocompromised patients is progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN), with early involvement of posterior pole and rapid progression. There is minimal vitreous inflammation despite extensive retinal involvement, particularly the deep retina.[26] In a large case series by Engstrom and colleagues in 1994, two-thirds of eyes with the disease progressed to no light perception (NLP) within 4 weeks of onset.[27]

Fifty percent of patients with Behcet disease have ocular manifestations while it is the presenting symptom in only twenty percent of patients.[28] The most common presentation in Behcet disease is panuveitis with the disease becoming bilateral in the majority with a chronic, relapsing course. Anterior segment inflammation usually presents as non-granulomatous acute uveitis with or without hypopyon. Hypopyon typically moves freely with shifting head positions and is present in a white eye i.e., without ciliary injection. The media haze or vitritis may be significant.

Retinitis is the second most common posterior segment finding after retinal vasculitis, which affects veins more than arteries in Behcet disease. [29] Retinitis manifests as patchy areas of focal retinal whitening attributed histologically to either retinal vasculitis, choroidal occlusive vasculitis, or primary focal retinal inflammation.[29] These areas of retinitis are deeper than the location of the cotton wool spots, larger when they occur in the posterior pole than in the periphery, occasionally associated with hemorrhage and usually resolve without any apparent retinochoroidal scarring within 1 or 2 weeks of starting immunosuppressive therapy. These focal patches of deep retinitis are proposed to be the earliest and the most common sign of disease reactivation.[29] Retinal atrophy may follow after the resolution of exudates and hemorrhages. Cystoid macular edema as a result of vascular leakage or optic disc involvement is another important finding.

Ocular manifestations of cat scratch disease include Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome or neuroretinitis. Neuroretinitis may present typically with optic nerve edema, macular star formation, and features of vasculitis. Discrete white retinal and chorioretinal lesions may be a more common finding than the 'classic' macular star. Other posterior segment findings include intermediate uveitis, granulomas, choroiditis, angiomatosis lesions, and serous retinal detachments.[30]

Retinitis in Rocky Mountain spotted fever presents in the form of white retinal lesions, typically adjacent to retinal vessels with mild to moderate vitreous inflammation. It is usually self-limiting with the resolution of white retinal lesions with or without scarring in several weeks.[31]

Toxocara retinochoroiditis can present acutely as a hazy, ill-defined white lesion with overlying vitritis. The lesion is seen as a distinct, well-demarcated, elevated white mass ranging from one-half to four disc diameters in size after the resolution of the inflammation with surrounding retinal pigment epithelium disturbance. The most common ocular feature, however, is posterior pole granuloma seen in 25% to 50% of patients.[32]

Chikungunya retinitis may morphologically mimic herpetic retinitis; however, there is a markedly less vitreous reaction and confluent posterior pole retinitis. The absence of a history of fever, joint pains, and skin rash before the onset of visual symptoms can differentiate chikungunya from the acute retinal necrosis. Posterior uveitis can present with no involvement of the anterior segment. Posterior pole or macular retinochoroiditis is quite specific but carries a very poor visual prognosis. Other posterior segment signs include optic neuritis, neuroretinitis, and retrobulbar neuritis.

In DUSN, there are multifocal gray-white evanescent lesions at the level of the outer retina, typically clustered in one segment of the fundus. These evanescent lesions are thought to be related to host immune response to the nematode in subretinal space and characteristically migrate according to the worm's location. In the later stages of the disease, there may be sequelae of degenerative changes in the RPE and retina, retinal artery narrowing, and optic atrophy.

Chorioretinitis in sarcoid uveitis is seen typically as multiple small round chorioretinal lesions frequently seen in the inferior peripheral fundus that heal with hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation.

Evaluation

Ocular Investigations

Focal posterior retinitis can be autoimmune or infective in origin. Organisms implicated include Toxoplasma gondii, Rickettsia (Indian tick typhus- Rickettsia conorii; epidemic typhus- Rickettsia prowazekii), Orientia tsutsugamushi (scrub typhus), Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), Bartonella henselae, West Nile virus, dengue virus, chikungunya virus, Rift valley fever virus, herpetic viruses, and measles virus (subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE)) besides metastatic endophthalmitis. It is essential to find the etiology of posterior focal retinitis as it is vision-threatening, and early treatment is imperative. Various serological tests and molecular assays are required to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Clinical judgment, based on fundus findings and information obtained from investigations such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA), may play a crucial role in the management of such patients.[33]

CMV retinitis and toxoplasma retinitis are essentially clinical diagnoses. In doubtful cases, PCR analysis of ocular fluids for CMV, HSV, VZV, and toxoplasma can be done. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) shows abnormal hyperreflectivity of all retinal layers at sites of active Toxoplasma infection, while fluorescein angiography demonstrates early blockage with subsequent leakage of the lesion.[34] In necrotizing retinitis, the OCT shows fragmentation of retinal tissue.[35]

American Uveitis Society in 1994 defined ARN on the basis of the following clinical characteristics: 1 or more foci of retinal necrosis with discrete borders located in the peripheral retina, a rapid progression in the absence of antiviral therapy, circumferential spread, evidence of occlusive vasculopathy with arterial involvement, and a prominent inflammatory reaction in the vitreous and anterior chamber.[36] In cases with a diagnostic dilemma, polymerase chain reaction testing for herpesviruses (VZV, HSV, CMV, EBV) and toxoplasmosis of aqueous or vitreous humor to rule out other etiologies should be done. Testing for HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), FTA-ABS (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption) and RPR (rapid plasma reagin), erythrocyte sedimentation rate, toxoplasmosis titers, purified protein derivative skin test (PPD), and chest radiograph can help in confirmation or ruling out other masquerades. However, treatment should not be withheld while awaiting test results.

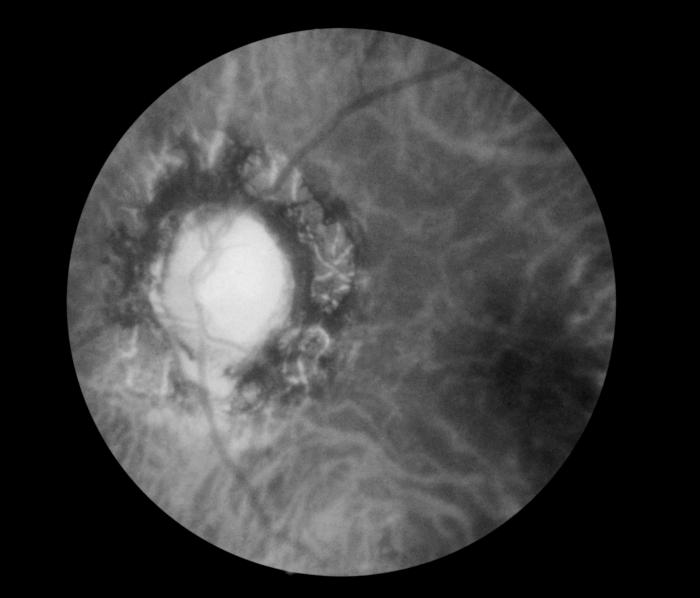

For ocular Behcet disease, fundus fluorescein angiography is essentially the gold standard in the evaluation of the activity and extent of retinal vasculitis. A fern-like pattern of leakage due to diffuse capillaritis in mid-phase of the angiogram is classical of Behcet disease.[37] Vessel wall staining and leakage suggest increased vascular permeability caused by the breakdown of the inner blood-retinal barrier. Not just diagnosis, but fundus fluorescein angiography(FFA) also helps in monitoring response to treatment. OCT is used for quantifying macular edema and assessment of the integrity of the inner segment-outer segment, which strongly correlates with visual acuity.

In short, ocular investigations in cases with retinitis include

- FFA

- OCT

- Slit-lamp photograph

- Ultrasound- to rule out retinal detachment and to document the severity of vitreous inflammation when the media is very hazy.

- Culture sensitivity (bacterial and fungal) and staining (KOH and Gram staining) of the aqueous or vitreous in suspected cases of endophthalmitis

- PCR for bacteria, fungi, Toxoplasma, HSV, HZV, CMV of aqueous and vitreous humor depending on the clinical presentation

- Retinal or chorioretinal biopsy or fine-needle aspiration biopsy

- Visual fields may show an absolute defect with a breakout to the periphery especially if the retinitis lesions are within 1 disc diameter of the optic disc in toxoplasmosis.[38]

Systemic Investigations

Depending upon the clinical presentation and ocular imaging, an appropriate case-based approach to order relevant systemic investigations needs to be undertaken.

The systemic investigations include a combination of:

- IgM and IgG for herpetic viruses (herpes simplex, Varicella zoster, and cytomegalovirus)

- IgG and IgM levels for Borrelia

- Weil–Felix test (WFT) (OX 2, OX K, and OX 19) for Rickettsia

- IgM and IgG for chikungunya and dengue

- Bartonella serology

- HIV

- CD4 count

- Toxoplasma IgG and IgM

- Hemogram with erythrocyte sedimentation rate,

- Liver function tests,

- Kidney function tests,

- Blood and urine culture,

- Chest X-ray/HRCT (high resolution computed tomogram) of chest

- Random/fasting/postprandial blood sugar, HbA1c

- Imaging for finding foci of infection in metastatic endophthalmitis

- Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA)/ VDRL for syphilis

- Mantoux (tuberculin skin test),

- Interferon-gamma release assay

- ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme)

- HLA B51 and pathergy test for Behcet disease

- CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) for VDRL

- CSF for antimeasles antibody and EEG (electroencephalogram) for SSPE

- Specific investigations for other causes

- Investigations for connective tissue disorders

- Blood pressure (malignant hypertensive retinopathy may be misdiagnosed as retinitis)

Treatment / Management

Treatment of retinitis is primarily directed at the source of infection or against the abnormal immune response in autoimmune diseases. In some cases, local therapy via injections or implants might suffice, but oral or intravenous medications are sometimes necessary as some of these are potentially blinding conditions with the possibility of contralateral spread. Laser procedures or surgery have been described for some infections to prevent complications like macula-off retinal detachment (RD).

In immunocompetent patients, Toxoplasma-related chorioretinitis is usually a self-limited infection and generally resolves spontaneously in 4 to 8 weeks. However, it is recommended to treat lesions within the vascular arcades or adjacent to the optic disk/fovea, those larger than 2 optic disk diameters to reduce the chance of vision loss, or when the induced vitreal inflammatory response has dropped vision below 20/40 in a previously 20/20 eye or at least has sustained a two-line drop in vision. Multiple drug combinations have been studied for treating toxoplasma chorioretinitis, including the classic triple-drug therapy (pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and corticosteroids); clindamycin, and steroid; and trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole.

In 1992, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (160 to 800 mg bid for 4 to 6 weeks) was studied as a new treatment option for ocular toxoplasmosis and was found to be a safe and effective substitute for sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine in treating ocular toxoplasmosis.[39] As the drug combination can cause bone marrow suppression, baseline laboratory tests, including a complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, along with follow-up testing, should be considered. Besides treating the active infection, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole has a prophylactic role in preventing recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis.[40]

Recently Soheilian et al. compared the efficacy of local treatment with intravitreal injection of clindamycin and dexamethasone with the classic triple-drug treatment and found no significant difference between the two groups.[41] The advantages of the local delivery of high concentrations of therapeutics into the vitreous cavity and retina, while reducing systemic adverse effects and ensuring greater patient compliance has made it an acceptable alternative to classic therapy in refractory disease.[42] Also, in early pregnancy (up to 18 weeks), local intervention with intravitreal clindamycin (1 mg/0.1 ml) and dexamethasone (400 mcg/0.1 ml) could be considered to prevent the possible adverse effects of antiparasitic agents. Spiramycin can also be used as it does not cross the placenta readily.[43] However, in immunocompromised patients, systemic therapy is still recommended to prevent toxoplasmosis-related complications in the fellow eye or elsewhere in the central nervous system. A systematic review has shown the widespread use of corticosteroids as adjunctive treatment toxoplasmosis mainly as anti-inflammatory agents to control inflammation and thus minimize damage to ocular tissues. Practices related to initiating corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg) vary with the majority starting them after three days.

For CMV retinitis, currently available therapies include intravenous and intravitreal ganciclovir and foscarnet, intravenous cidofovir, and oral valganciclovir. The cause of immunocompromise should be treated adequately. First-line treatment of CMV retinitis is usually oral valganciclovir, which is a prodrug of ganciclovir with higher bioavailability. With intravenous ganciclovir, induction therapy is given at a dose of 5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 14 to 21 days followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg/kg/day while for valganciclovir, it is 900 mg twice daily during induction therapy, followed by 900 mg daily for maintenance.[44][45]

The principal side effect of ganciclovir and valganciclovir is myelosuppression; hence blood counts monitoring needs to be done. In patients with immediately sight-threatening lesions (lesions close to the macula or optic nerve head), local therapy with intravitreal injection of ganciclovir (2 mg/0.1 ml) or foscarnet (2.4 mg or 1.2 mg /0.1 ml) with concurrent systemic therapy can be given.[46] Intravitreal ganciclovir implants containing a minimum of 4.5 mg ganciclovir can also be surgically implanted through the pars plana. They act for 6 to 8 months and have a low-risk profile; however, they do not afford any protection for the fellow eye or other visceral involvement. Immune recovery uveitis is another issue after starting antiretroviral therapy in AIDS with CMV retinitis and may present with anterior segment inflammation, posterior synechia, cataract, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, and epiretinal membrane.

Central Disease Control (CDC) guidelines recommend that for AIDS-related CMV retinitis, chronic maintenance therapy be continued until immune reconstitution occurs, defined as a sustained (>6 months) increase in the CD4+ lymphocyte count to greater than 100 to 150 cells/mL as ganciclovir is not virucidal.[47]

Treatment of ARN should be initiated early with the objective of hastening the resolution of disease in the infected eye and preventing contralateral disease. Initially, patients should be hospitalized and treated with a 10 to 14-day course of intravenously administered acyclovir 10 to 15 mg/kg every 8 hours, followed by oral acyclovir 800 mg five times a day for 6 to 12 weeks.[48] Recently, outpatient treatment with orally administered valacyclovir at 2 g TID has been shown to achieve systemic levels similar to intravenous acyclovir.[49][50]

Local treatment with intravitreal injections of ganciclovir (2 mg/0.1 mL) is effective in treating sight-threatening herpetic infections with fovea or optic disc involvement. Oral steroids should be administered under antiviral cover, starting 24 to 48 hours after antiviral therapy, particularly in cases with optic nerve involvement. The role of prophylactic laser posterior to the area of active retinitis (wherever possible through the hazy media) to prevent RD in the setting of recent ARN still stands doubtful.

Early surgery for retinal detachments in ARN is crucial even though vitrectomies are difficult with high chances of redetachment due to increased risk of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) in these patients.[51] Typically, multiple breaks (like a sieve) at the periphery or posterior pole are seen with varying grades of PVR.

The aim of treatment in Behcet disease is to control the inflammation, reduce the frequency of recurrences, and avoid complications. Corticosteroids and immunomodulatory therapy are the mainstays of treatment as it is a chronic relapsing autoimmune disease.

First attacks of anterior uveitis are treated with topical corticosteroid drops and cycloplegic agents to prevent synechiae formation and relieve photophobia and pain. For more severe and repeated attacks, subtenon injection of depot steroids or systemic steroids may be used for long term suppression of inflammation. Despite the absence of RCTs(randomized controlled trials), European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends that systemic steroids may be given in the form of high-dose systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day) or intravenous pulse methylprednisolone (1 g/day) administered for 3 consecutive days for rapid anti-inflammatory effect.[52]

As long term steroid therapy is associated with systemic and ocular side effects, patients need to be started on an immunosuppressive agent. Conventional immunosuppressive agents that have been used for the treatment of Behcet uveitis with posterior segment involvement include antimetabolites (methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate), calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine A, tacrolimus, sirolimus), and alkylating agents (chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide). Studies have also evaluated the use of biological agents like anti-TNF-alpha or IFN-alpha for treating severe retinal vasculitis secondary to Behcet disease.[53][54]

Although the majority of post fever retinitis recover with a good visual outcome over a 10- to 12-week period, systemic steroids may be used to control inflammation in posterior uveitis, panuveitis, and optic neuritis if an immune origin of the manifestation is considered. For focal retinitis clinically suggestive (aided with imaging modalities) of rickettsial disease (non-toxoplasma and non-viral/herpetic) empirically starting oral doxycycline before oral steroid may be prudent.[33] Macular edema after post-fever retinitis may respond favorably with intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial factor (anti-VEGF) agents.[55]

Metastatic/endogenous endophthalmitis needs urgent control of the systemic infection or focus of infection. Ocular management includes intravitreal antimicrobial therapy and vitrectomy. The visual prognosis is usually poor in such cases.

SSPE is a fatal disease, and many drugs, including ribavirin, have been tried.

The cause of immunocompromise (if present) should be treated optimally.

The patients should be monitored closely for the progression of the disease, systemic/contralateral involvement, and complications of disease/therapy.

In all cases of infective retinitis, the antimicrobial should be started first, and then steroids can be started. Starting steroids in a case of infective retinitis/panuveitis without antimicrobial cover may cause severe ocular damage and even maybe life-threatening in cases with systemic disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Retinitis due to CMV, toxoplasma, and viral etiology has to be differentiated from each other based on clinical features or, if needed, other ocular or systemic ancillary investigations.

The differential diagnosis for Behcet disease includes a variety of infectious and noninfectious causes of acute nongranulomatous anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, occlusive retinal vasculitis, focal or multifocal retinitis, and necrotizing retinitis. Behçet uveitis typically has a sudden onset of symptoms with improvement followed by recurrence of inflammatory signs. Specifically, metastatic endophthalmitis must be ruled out in all cases of retinitis, especially bilateral ones.

Prognosis

The visual outcomes of all these pathologies are variable depending on the infecting microbe, the immune status of the patient, and specific sites of retinal involvement. For example, herpetic viral infections are rapidly progressive and can lead to retinal detachment, while Toxoplasma infections are usually self-limited and can be observed.

Vision loss occurs when the retinitis involves the fovea or optic disc, or there is the development of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment when breaks occur in the thin, necrotic retina. Patients may also complain of visual loss due to the formation of absolute scotoma in the area of retinal necrosis.

The vision loss of a patient with toxoplasmosis may also be due to the vitreous inflammation being so severe as to cause a drop in vision or choroidal neovascularization occurring as a late complication of the disease. Macular scar and optic atrophy can cause permanent visual impairment.

Visual outcomes in ARN are generally poor mostly due to retinal detachment (20% to 73% incidence in 3 months) but might also be due to chronic vitritis, epiretinal membrane, macular ischemia, and optic neuropathy.[47]

PORN syndrome is a rare but visually blinding complication of AIDS. The prognosis is dismal with disease progression and/or recurrence despite aggressive therapy with intravenous antiviral drugs. These patients usually end up with total retinal detachments and minimal to no perception of light subsequently.[2]

SSPE is a potentially lethal disease with a very guarded prognosis both in terms of salvage of vision as well as life.

Post-fever retinitis usually has good visual prognosis.

Complications

- Retinal breaks

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

- Optic neuropathy

- Optic atrophy

- Macular scar

- Epiretinal membrane/vitreomacular traction

- Cystoid macular edema

- Choroidal neovascularisation

- Complicated cataract

- Chronic vitritis

- Macular ischemia

- Glaucoma

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Phthisis[56]

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients with these visually disabling forms of retinitis should be informed about the severity of the disease, and it's complications as well as prognosis. The need and importance of urgent treatment should be well emphasized to ensure patient compliance.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As discussed above, these viral illnesses may result in serious complications and profound vision loss. Hence, it is important to work up all cases of posterior uveitis to rule out an infectious etiology and act promptly in managing these diseases. Also, since most of these patients are immunocompromised, healthcare workers should do a thorough systemic evaluation for these patients and treat the patient as a whole.

The diagnosis and management of necrotizing retinopathies like ARN is complex, and only a prompt diagnosis can help salvage vision. Healthcare workers, including primary care physicians and nurses who see patients with herpes infection of the eye, should immediately refer these patients to an ophthalmologist. The goal of immediate treatment of such patients is mainly to decrease the incidence in the fellow eye.