Introduction

The anatomy of the head and neck is very complicated secondary to the numerous fine structures that have a variable course and depth as they traverse through the tissue. There are several very important neurovascular structures anatomically situated in the head and neck, which may suffer a potential injury during surgical dissection. The neck divides into subdivisions and compartments that aid in the organization and help make sense of this complex region. The anterior and posterior triangles are the two primary subdivisions and are delineated by easily recognized anatomic structures. Each triangle houses muscles, nerves, vasculature, lymphatics, and adipose tissue. The objective of this article is to provide an in-depth understanding of the anatomy of the triangles of the neck and to relate this information to relevant clinical and surgical considerations.

Structure and Function

Anatomic Boundaries

Anterior Triangle

The anterior triangles refer to bilateral anatomic subdivisions of the neck comprising the anterior surface of the neck, deep to the superficial cervical fascia and platysma muscle.

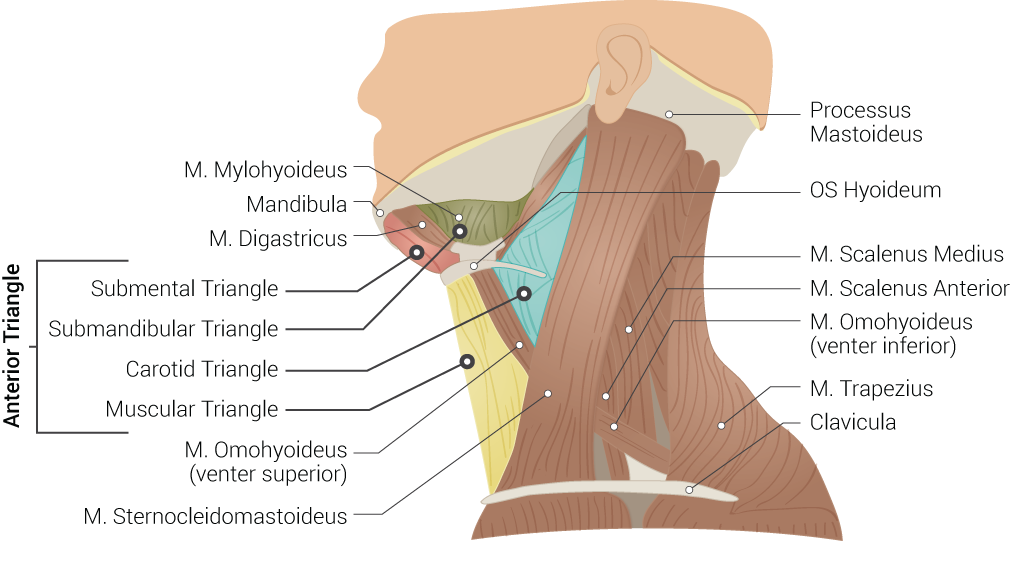

Laterally, the anterior triangle is bounded by the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Its superior border is the inferior border of the mandible. Medially, the boundary is the midline of the neck. The anterior triangle can further subdivide into four sub-triangles. The submandibular and submental triangles are the superior divisions, while the muscular and carotid triangles compose the inferior divisions of this anterior neck compartment. The submandibular triangle is delineated by the inferior border of the mandible and the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle. The submental triangle is demarcated by the hyoid bone, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, and the midline of the neck.[1] The muscular triangle is outlined by the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid and superior belly of the omohyoid, the midline of the neck, and the hyoid bone. The outline of the carotid triangle is the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, the superior belly of the omohyoid, and the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles.[2] The investing layer of the deep cervical fascia encases all of the infrahyoid muscles and forms the superficial boundary of the entire anterior triangle. The deep boundary of the carotid and muscular triangles is composed of the pretracheal layer of the deep cervical fascia, while the mylohyoid muscle forms the deep boundary of the submandibular and submental triangles.[3] The submandibular gland, a major salivary gland, emerges from the lateral aspect of the mylohyoid muscle and occupies most of the submandibular triangle.

Posterior Triangle

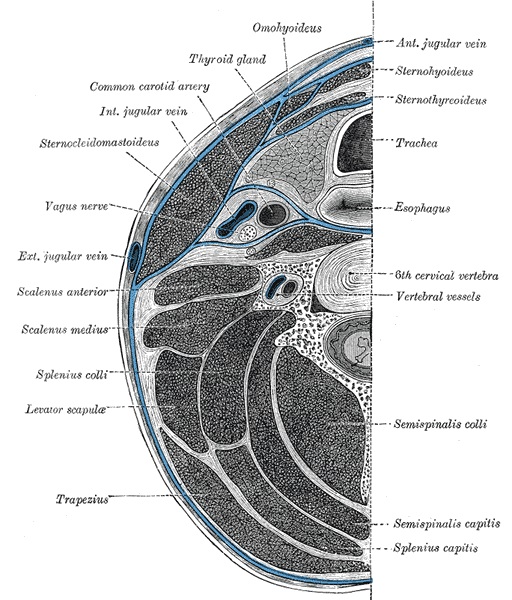

The posterior triangle of the neck is posterior to the anterior triangle. The boundary of this triangle is the posterior surface of the sternocleidomastoid, the anterior surface of the trapezius, and the middle third of the clavicle. The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles join at the superior nuchal line, which forms the apex of the triangle. The investing layer of deep cervical fascia makes up the superficial border of the posterior triangle, while the prevertebral fascia makes up the floor. The inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle passes deep to the sternocleidomastoid and crosses through the posterior triangle, further dividing it into the occipital and subclavian sub-triangles.[4]

Function of the Neck Triangles

The anterior and posterior triangles of the neck provide a natural framework to organize the numerous contents of the neck into well-defined anatomic subdivisions. The muscles, bones, and fascia of the cervical region form natural boundaries that enclose various other structures, including muscles, nerves, vasculature, and lymphatics. The following sections will further define the anterior and posterior triangles, clarify the contents of each, and discuss their clinical and surgical relevance.

Embryology

The anatomic structures of the head and neck derive from the pharyngeal apparatus, which is an embryologic structure that contains six distinct arches organized in a craniocaudal fashion. Each arch is composed of a central layer of mesoderm and neural crest cells surrounded internally by endoderm and externally by ectoderm. The mesodermal core of each arch forms the corresponding arteries, nerves, muscles, and skeletal structures.[5] Many anatomic relationships among mature structures of the head and neck can be understood based upon their origins from the pharyngeal apparatus. For example, the anterior belly of the digastric muscle arises from the mesoderm of the first arch, while the posterior belly arises from the mesoderm of the second arch. The cranial nerve derived from the first arch is the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, while the cranial nerve derived from the second arch is the facial nerve. These embryologic origins adequately explain the unique innervation pattern of the muscles.[6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Anterior Triangle

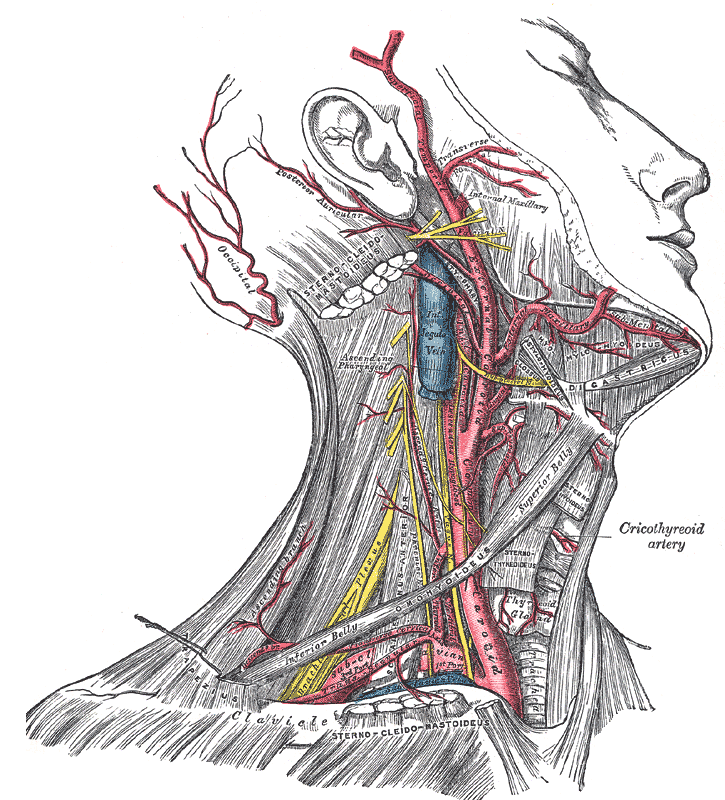

The carotid sheath is a thick layer of fascia that encases the superior portion of the common carotid artery, the proximal portion of the internal and external carotid arteries, the internal jugular vein and the vagus nerve. The carotid sheath emerges from the posterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid. It ascends through the carotid triangle before its contents pass deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and continue along the lateral aspect of the neck. The common carotid artery runs anteromedial to the internal jugular vein within the sheath and bifurcates between the third and fourth cervical vertebrae, which aligns with the superior border of the thyroid cartilage. The internal carotid artery does not give off any branches in the neck and ascends posterior to the external carotid artery to enter the cranial cavity. The external carotid artery branches directly following the bifurcation and provide blood supply to most structures of the head and neck.[7]

There are eight branches of the external carotid artery, though only the four most proximal are within the boundaries of the anterior triangle. The superior thyroid artery exits from the anterior aspect of the carotid artery and descends to supply the superior pole of the thyroid gland, the thyrohyoid and cricothyroid muscles, and the internal larynx via the superior laryngeal artery. The ascending pharyngeal artery arises from the posterior aspect of the external carotid, just superior to the superior thyroid artery. This artery dives deep to pierce the pretracheal fascia and supply pharyngeal constrictor muscles. The lingual artery originates from the anterior surface of the external carotid and immediately passes deep to the mylohyoid muscle to supply the muscles of the tongue and the sublingual salivary gland. The facial artery also branches off of the anterior surface of the external carotid just superior to the lingual artery. It then passes deep to the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles and continues its tortuous course superficial to the mylohyoid muscle before hooking over the inferior edge of the mandible just anterior to the masseter muscle. The facial artery supplies the submandibular salivary gland, the soft palate, and many more structures of the face via its numerous branches.[8]

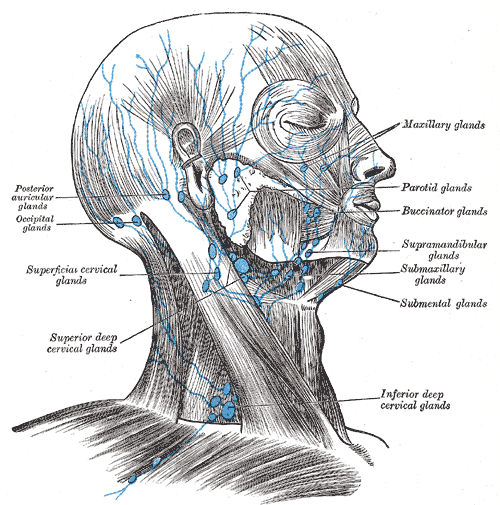

The anterior triangle is home to lymph nodes, including the submandibular and submental node basins. The submandibular nodes exist deep to the submandibular gland within the submandibular triangle. They drain the oral cavity and some of the soft tissue structures of the lower face. The submental lymph nodes lie within the submental triangle and drain the lower lip, floor of the mouth, and apex of the tongue. Both of these groups of lymph nodes are clinically important in deep neck space infections and also head and neck cancer.[9]

Posterior Triangle

The most prominent vascular structure of the posterior triangle is the subclavian artery. This artery is found in the subclavian triangle and becomes ensheathed in prevertebral fascia as it crosses deep to the anterior scalene muscle. Directly medial to the anterior scalene, the subclavian artery gives off the thyrocervical trunk, which further branches into the suprascapular, transverse cervical, ascending cervical, and inferior thyroid arteries. The suprascapular and transverse cervical arteries course laterally over the anterior surface of the anterior scalene and supply the muscles of the scapula and the trapezius, respectively. The ascending cervical artery ascends within the prevertebral fascia to supply the deep muscles of the neck. The inferior thyroid artery continues superomedially to the inferior lobe of the thyroid, eventually anastomosing with the superior thyroid artery.[10]

There are numerous lymph nodes associated with the posterior triangle that drain local structures and move lymphatic fluid along the chain. The posterior auricular and occipital nodes lie near the apex of the triangle, on the superficial surface of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius tendons. The superficial cervical nodes exist on the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid, while the deep cervical nodes are on the deep surface of the sternocleidomastoid. The posterior cervical nodes accompany the jugular vein as it pierces the investing fascia and enters the posterior triangle. The supraclavicular lymph nodes are on the superior surface of the middle third of the clavicle.[9]

Nerves

Anterior Triangle

The anterior triangle of the neck contains several important nerves that not only innervate local structures but also pass through the region on their way to other destinations. The vagus nerve runs in the carotid sheath between the carotid artery and the internal jugular vein. It gives off its pharyngeal branches at the superior margin of the anterior triangle supplying motor input to the internal pharyngeal muscles. The superior laryngeal nerve branches from the vagus nerve just inferior to the pharyngeal branches and divides into the external and internal laryngeal nerves. The internal laryngeal nerve pierces they thyrohyoid membrane and provides sensory innervation to the larynx above the vocal cords. The external laryngeal nerve innervates the cricothyroid muscle.[11]

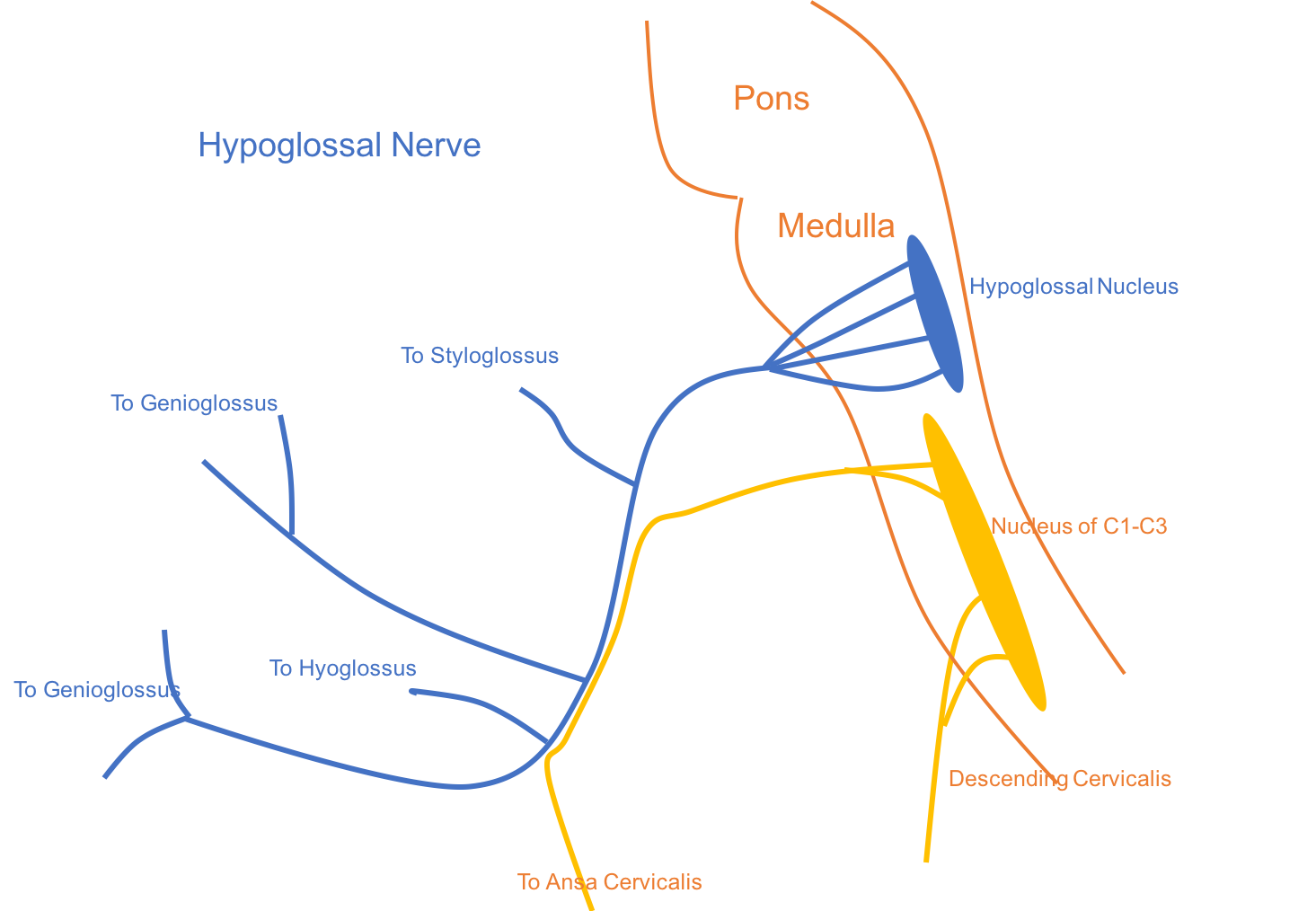

The hypoglossal nerve, or cranial nerve XII, descends posterior to the internal carotid artery and first appears in the carotid triangle as crosses the lateral surface of the internal and external carotid arteries. The nerve continues medially and passes superficial to the lingual artery before it dives deep to the posterior belly of the digastric and stylohyoid muscles. It then courses deep to the mylohyoid muscle and runs beneath the submandibular triangle en route to innervate the intrinsic muscles of the tongue.

The ansa cervicalis is a part of the cervical plexus and forms a loop of nerves that occupy the anterior triangle. It is composed of a superior and inferior root. The superior root arises from the anterior ramus of the first cervical spinal nerve. It briefly travels with the hypoglossal nerve before it descends along the anterior surface of the carotid sheath. However, the nerve to the thyrohyoid is a branch of the superior root that travels with the hypoglossal nerve for an extended distance before it separates to innervate the thyrohyoid muscle. The inferior root originates from the anterior rami of the second and third cervical spinal nerves and descends along the lateral surface of the carotid sheath. The superior and inferior loop join around the level of the fifth cervical vertebra to form a loop. This loop gives branches to innervate the omohyoid, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid.[12]

Branches of both the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves are responsible for the innervation of the carotid body and carotid sinus, which function to regulate blood pressure and blood oxygen content, respectively. This article will cover the clinical implications of each of these structures in the upcoming sections.

Posterior Triangle

The spinal accessory nerve, or cranial nerve XI, can be found within the posterior triangle as it innervates the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. After exiting the skull via the jugular foramen, the nerve descends along the deep surface of the sternocleidomastoid and gives off motor branches to the muscle. It then appears from posterior to the sternocleidomastoid and traverses the posterior triangle in an inferior and posterior direction before it passes deep to the trapezius.[13]

The nerves that supply cutaneous sensation to the majority of the cervical region are also related to the posterior triangle. Along with the ansa cervicalis, these four nerves also arise from the cervical plexus and are derived from the anterior rami of the second, third, and fourth cervical spinal nerves. The nerves emerge from the investing fascia near the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid near its midpoint and course between the investing and superficial fascia toward their final destinations. The greater auricular and lesser occipital nerves ascend to innervate the skin of the parotid, mastoid, and lesser occipital regions. The transverse cervical nerve crosses medially over the sternocleidomastoid and innervates most of the skin of the anterior neck. The supraclavicular nerve courses inferiorly and branches broadly to supply cutaneous sensation to the area over the clavicle and the first two ribs.[14]

Muscles

Anterior Triangle

The infrahyoid, or strap, muscles are paired bilateral muscle pairs that occupy the area between the sternum and hyoid bone. The innervation of each of the strap muscles is from the ansa cervicalis. The sternothyroid and thyrohyoid are relatively shorter muscles and are deep to the longer omohyoid and sternohyoid muscles. The sternothyroid originates manubrium just lateral to the midline and inserts on the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage. Its function is to depress the thyroid cartilage. The thyrohyoid is the superior continuation of the sternothyroid. It originates from the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage and inserts on the greater horn and body of the hyoid bone. When the hyoid bone is fixed, it elevates the thyroid cartilage. When the thyroid cartilage is fixed, it depresses the hyoid. The sternohyoid is also just lateral to the midline and is superficial to both the sternothyroid and thyrohyoid. It originates from the sternoclavicular joint and neighboring manubrium and inserts on the body of the hyoid bone. It depresses the hyoid bone during swallowing. The omohyoid muscle is lateral to the sternohyoid and also superficial to the sternothyroid and thyrohyoid. It has two bellies joined by an intermediate tendon. The superior stomach separates the muscular and carotid triangles. It originates from the intermediate tendon posterior to the sternocleidomastoid and inserts on the body of the hyoid bone lateral the sternohyoid. The posterior belly of the omohyoid is not contained within the anterior triangle, but passes through the posterior triangle of the neck and attaches to the superior aspect of the scapula. The omohyoid depresses the hyoid bone.[15]

Additional muscles that are related to the anterior triangle of the neck include the digastric, stylohyoid, and mylohyoid. The digastric muscle has an anterior and posterior belly joined by a common tendon that attaches to the body of the hyoid bone. The anterior belly originates from the digastric fossa on the internal surface of the body of the mandible and is innervated by the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The posterior belly originates from the medial surface of the mastoid process and is innervated by the facial nerve. The digastric muscle functions to elevate the hyoid bone and depress the mandible.[6] The stylohyoid follows a similar course to the posterior belly of the digastric, and together these muscles divide the carotid from the submandibular triangle. The stylohyoid originates from the styloid process at the base of the skull and inserts on the body of the hyoid and the digastric tendon. The stylohyoid receives its innervation by the facial nerve and retracts the hyoid bone during swallowing. The mylohyoid constitutes the deep surface of the submandibular and submental triangles and forms the floor of the oral cavity. Its origin is from the mylohyoid line of the internal surface of the body of the mandible, and it inserts on the body of the hyoid and the contralateral mylohyoid muscle at the midline. Its nerve supply is from the nerve to mylohyoid, which branches from the inferior alveolar branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The mylohyoid elevates and supports the floor of the oral cavity.[16]

Posterior Triangle

The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles contribute to the boundaries of the posterior triangle. These relatively large muscles are both wrapped in investing fascia and are innervated by the spinal accessory nerve. The sternocleidomastoid has an origin at both the manubrium and the medial end of the clavicle, and it inserts at the mastoid process and superior nuchal line of the occipital bone. Its functions in ipsilateral flexion of the neck and contralateral rotation of the head. The trapezius originates broadly from the superior nuchal line and the spinous processes of C2 through T2 vertebrae, and it inserts on the spine of the scapula, acromion process, and lateral end of the clavicle. It functions in numerous movements of the scapula, including elevation, lateral rotation, retraction, and depression.[4] While the superior belly of the omohyoid muscle is in the anterior triangle, the inferior belly bisects the posterior triangle. The inferior belly originates from the superior border of the scapula near the suprascapular notch and inserts on the intermediate tendon deep to the sternocleidomastoid. It shares a common innervation and action with the superior belly, as discussed in the discussion of the musculature of the anterior triangle.[15]

Physiologic Variants

Though the anatomy of the triangles of the neck is fairly well-defined, there are many documented naturally occurring variants. One such variation involves the course of the spinal accessory nerve, which is associated with both the anterior and posterior triangles. The nerve exits the cranial cavity through the jugular foramen and descends alongside the internal jugular vein, only briefly passing through the borders of the carotid triangle. It is generally accepted that the accessory nerve crosses laterally to the internal jugular vein at the level of the third cervical vertebra on its path to innervate the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. However, one study of 207 neck dissections found that the nerve crossed medially to the vein in six cases. Some cadaveric studies have even reported an incidence as high as one-third of individuals with the nerve passing medial to the vein.[17]

There also exists another rare variant of the spinal accessory nerve in which the nerve splits into a superior and inferior division within the anterior triangle. Another similar study demonstrated this variant in three of 133 neck dissections. In such cases, the superior division enters the sternocleidomastoid and supplies its motor innervation, while the posterior division follows an extended course through the carotid triangle before it passes deep to the sternocleidomastoid and through the posterior triangle to supply the trapezius.[18]

Surgical Considerations

Anterior Triangle

A thorough understanding of anatomy is essential to avoiding injury when performing operations in this area. Meticulous care is necessary to maintain the integrity of many fine and critical structures and to avoid unintended consequences. The carotid endarterectomy is a common operation to alleviate significant stenosis of the internal carotid artery. Caution must be taken in the approach, as the roots of the ansa cervicalis run on the anterior and lateral surfaces of the carotid sheath. The carotid sinus and carotid branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve are also susceptible to injury during the endarterectomy. Inadvertent or excessive stimulation of either structure may result in profound intraoperative bradycardia and hypotension, while damage may result in a diminished or completely absent baroreceptor reflex. Injury to the vagus nerve can result in permanent or temporary dysphagia, hoarseness aspiration.[19]

Thyroid and parathyroid surgery also require dissection of the anterior triangle as these structures lie within the pretracheal layer of the deep cervical fascia. The strap muscles must be delicately retracted or divided using electrocautery to visualize the thyroid gland adequately. The neurovascular structures of the thyroid and parathyroid glands are deep to the strap muscles. The surgeon must pay particular attention to the superior laryngeal artery and nerve near the superior pole of the thyroid. The superior thyroid artery must be ligated distal to the branch point of the superior laryngeal artery; otherwise, the vascular supply of the larynx could become compromised. Though not as severe as recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, injury to the superior laryngeal nerve may result in mild voice changes such as hoarseness or voice fatigue.[11] Bilateral superior laryngeal nerve injury, however, results in the loss of the laryngeal cough reflex, specifically due to the disruption of the internal laryngeal nerve. This condition places the patient at risk for aspiration pneumonia and other chronic problems.[20]

Posterior Triangle

Operations requiring dissection of the posterior triangle, the surgeon needs to be aware and careful as the spinal accessory nerve is at risk for injury. Due to the potential for permanent damage, it is often necessary to perform intraoperative nerve mapping via direct stimulation to avoid nerve injury. Injury to the spinal accessory nerve within the posterior triangle may result in weakness of shoulder elevation or arm abduction and permanent pain because the innervation to the trapezius becomes disrupted. The sternocleidomastoid is typically spared because its the spinal accessory nerve supplies its motor branches more proximally.[21]

The cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus are also relevant for anesthetic purposes. A bilateral superficial cervical plexus block can provide analgesia for procedures such as thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy, and carotid endarterectomy. To perform a bilateral superficial cervical plexus block, the clinician inserts a needle along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid just deep to the superficial fascia, and local anesthetic floods the region where the nerves emerge from the investing fascia. The patient may be asked to rotate his or her head to the contralateral side, which allows for easy visualization of the sternocleidomastoid. The clinician can perform this procedure with or without ultrasound guidance.[22]

Clinical Significance

Anterior Triangle

The internal jugular vein carries considerable clinical significance as it courses through the anterior triangle of the neck. The jugular venous pressure is a feature of the internal jugular vein and serves as a clinical measure of the function of the right side of the heart. In conditions such as inferior wall myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure, the forward flow of blood becomes impeded, and the pressure within the internal jugular vein rises as a consequence. This increased pressure causes the vein to appear grossly engorged, and the resultant waveform can be detected by a jugular venous pulse tracing. The internal jugular vein is also frequently used to establish central venous access for purposes such as parental nutrition, dialysis, and administration of chemotherapy drugs. Central access through the internal jugular vein typically has less adverse effects than the subclavian vein, and it can be easily localized using both surface anatomy and ultrasound guidance. However, the proximity of the internal jugular vein to the carotid artery poses the risk of potential puncture or hematoma.[23]

The carotid sinus and carotid body are at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery and serve important physiologic roles with clinical relevance. The carotid sinus is a baroreceptor that regulates blood pressure. It receives innervation from the carotid branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve. An increase in blood pressure causes increased tension within the sinus, which adjusts the autonomic activity and results in decreased blood pressure, bradycardia, and a decreased respiratory rate. As a result, the clinician can attempt gentle compression of the carotid sinus, referred to as a carotid sinus massage, to terminate supraventricular tachycardia and other cardiac arrhythmias. The carotid body is a chemoreceptor that detects blood oxygen content and complements the regulatory function of the carotid sinus. Its innervation derives from branches of both the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. In certain conditions of chronic hypoxia such as high altitude or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the carotid bodies can become overstimulated, leading to hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and possibly even neoplastic transformation.[24]

Posterior Triangle

Lymphadenopathy is a relatively common pathology of the cervical region and can occur in both the anterior and posterior triangle of the neck. Physical exam and clinical understanding of lymphatic drainage patterns are imperative to determine the underlying cause of the lymphadenopathy. Soft, tender lymph nodes are typically associated with infectious etiologies, such as pharyngitis or mononucleosis, while firm, rubbery lymph nodes are more likely to signify a neoplastic process. Cervical lymphadenopathy is often the presenting sign of head and neck cancers in the adult population, and further work-up is warranted to identify the source of the primary tumor.[25]