[1]

Hilton DA, Hanemann CO. Schwannomas and their pathogenesis. Brain pathology (Zurich, Switzerland). 2014 Apr:24(3):205-20. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12125. Epub 2014 Feb 25

[PubMed PMID: 24450866]

[2]

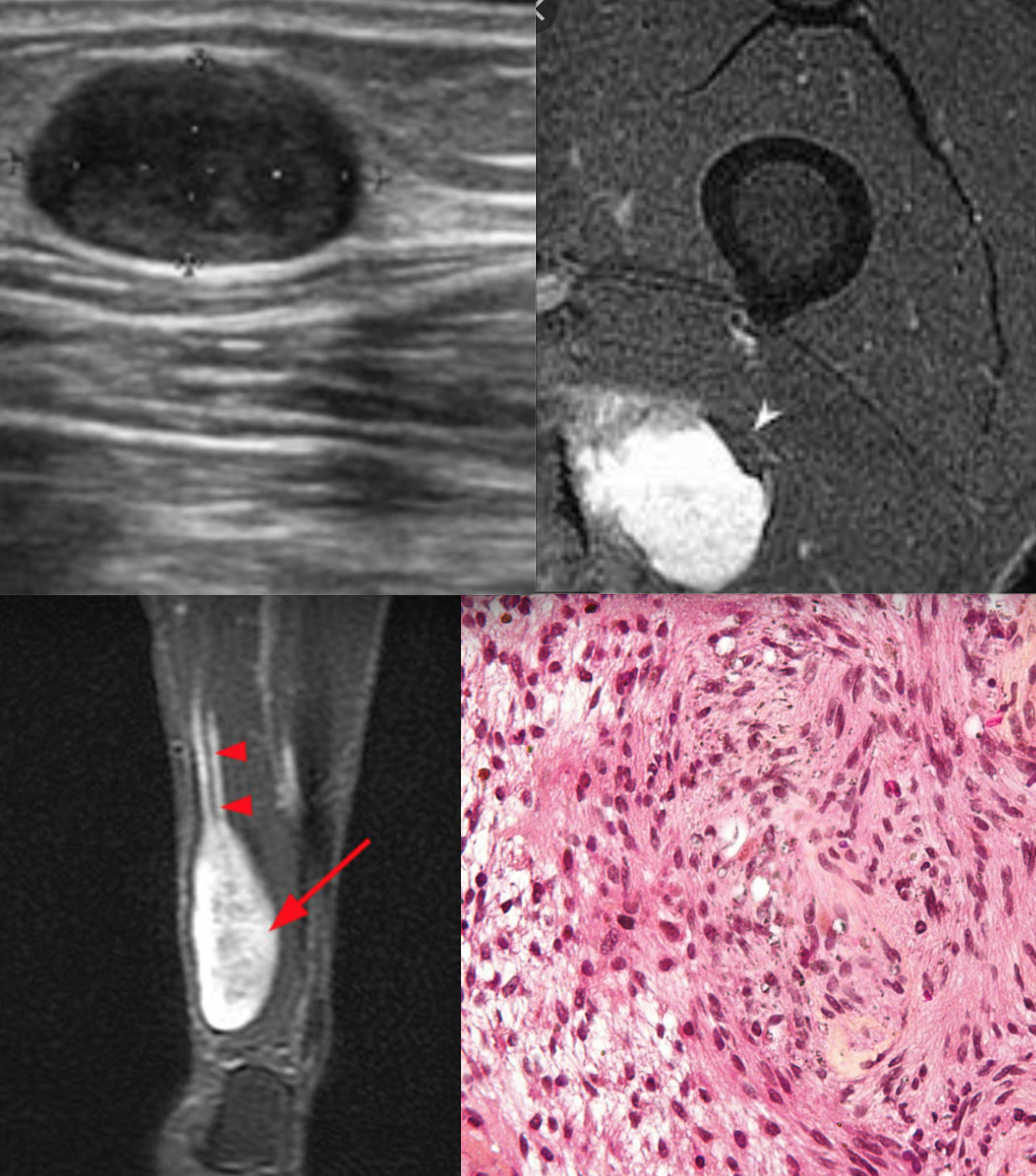

Pilavaki M, Chourmouzi D, Kiziridou A, Skordalaki A, Zarampoukas T, Drevelengas A. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: pictorial review. European journal of radiology. 2004 Dec:52(3):229-39

[PubMed PMID: 15544900]

[3]

Evans DG, Moran A, King A, Saeed S, Gurusinghe N, Ramsden R. Incidence of vestibular schwannoma and neurofibromatosis 2 in the North West of England over a 10-year period: higher incidence than previously thought. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2005 Jan:26(1):93-7

[PubMed PMID: 15699726]

[4]

Lin D, Hegarty JL, Fischbein NJ, Jackler RK. The prevalence of "incidental" acoustic neuroma. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2005 Mar:131(3):241-4

[PubMed PMID: 15781765]

[5]

Propp JM, McCarthy BJ, Davis FG, Preston-Martin S. Descriptive epidemiology of vestibular schwannomas. Neuro-oncology. 2006 Jan:8(1):1-11

[PubMed PMID: 16443943]

[6]

Tos M, Stangerup SE, Cayé-Thomasen P, Tos T, Thomsen J. What is the real incidence of vestibular schwannoma? Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2004 Feb:130(2):216-20

[PubMed PMID: 14967754]

[7]

Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, Perry A. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta neuropathologica. 2012 Mar:123(3):295-319. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0954-z. Epub 2012 Feb 12

[PubMed PMID: 22327363]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Weiss SW, Langloss JM, Enzinger FM. Value of S-100 protein in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors with particular reference to benign and malignant Schwann cell tumors. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1983 Sep:49(3):299-308

[PubMed PMID: 6310227]

[9]

Ogawa K, Oguchi M, Yamabe H, Nakashima Y, Hamashima Y. Distribution of collagen type IV in soft tissue tumors. An immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1986 Jul 15:58(2):269-77

[PubMed PMID: 3521829]

[10]

Kawahara E, Oda Y, Ooi A, Katsuda S, Nakanishi I, Umeda S. Expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A comparative study of immunoreactivity of GFAP, vimentin, S-100 protein, and neurofilament in 38 schwannomas and 18 neurofibromas. The American journal of surgical pathology. 1988 Feb:12(2):115-20

[PubMed PMID: 3124642]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[11]

Perry A, Roth KA, Banerjee R, Fuller CE, Gutmann DH. NF1 deletions in S-100 protein-positive and negative cells of sporadic and neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1)-associated plexiform neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. The American journal of pathology. 2001 Jul:159(1):57-61

[PubMed PMID: 11438454]

[12]

Crist J, Hodge JR, Frick M, Leung FP, Hsu E, Gi MT, Venkatesh SK. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Appearance of Schwannomas from Head to Toe: A Pictorial Review. Journal of clinical imaging science. 2017:7():38. doi: 10.4103/jcis.JCIS_40_17. Epub 2017 Oct 3

[PubMed PMID: 29114437]

[13]

Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2004 Apr:15(2):157-66

[PubMed PMID: 15177315]

[14]

Golan JD, Jacques L. Nonneoplastic peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2004 Apr:15(2):223-30

[PubMed PMID: 15177321]

[15]

Bhattacharyya AK, Perrin R, Guha A. Peripheral nerve tumors: management strategies and molecular insights. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2004 Aug-Sep:69(1-3):335-49

[PubMed PMID: 15527099]

[16]

Mrugala MM, Batchelor TT, Plotkin SR. Peripheral and cranial nerve sheath tumors. Current opinion in neurology. 2005 Oct:18(5):604-10

[PubMed PMID: 16155448]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[17]

Kim DH, Murovic JA, Tiel RL, Kline DG. Operative outcomes of 546 Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2004 Apr:15(2):177-92

[PubMed PMID: 15177317]

[18]

Nascimento AF, Fletcher CD. The controversial nosology of benign nerve sheath tumors: neurofilament protein staining demonstrates intratumoral axons in many sporadic schwannomas. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2007 Sep:31(9):1363-70

[PubMed PMID: 17721192]

[19]

Young ED, Ingram D, Metcalf-Doetsch W, Khan D, Al Sannaa G, Le Loarer F, Lazar AJF, Slopis J, Torres KE, Lev D, Pollock RE, McCutcheon IE. Clinicopathological variables of sporadic schwannomas of peripheral nerve in 291 patients and expression of biologically relevant markers. Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Sep:129(3):805-814. doi: 10.3171/2017.2.JNS153004. Epub 2017 Sep 8

[PubMed PMID: 28885122]