Introduction

The cerebral cortex is the outermost portion of the brain, containing billions of tightly packed neuronal cell bodies that form what is known as the gray matter of the brain. The white matter of the brain and spinal cord forms as heavily myelinated axonal projections of these neuronal cell bodies. The cerebral cortex has four major divisions known as lobes: the frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. Each of these lobes has developed evolutionarily distinct and important functions. The surface of the cortex has a characteristic 'bumps and grooves' appearance, with the bumps referring to foldings of the cortex known as gyri, and the grooves referring to the sulci, which separate them. These foldings allow for the large cortical volume to fit inside the limited space of the cranial vault.[1] The sulci are anatomical divides that separate the lobes from one another. The lateral cerebral fissure, also known as the Sylvian fissure, separates the temporal lobe from the parietal and frontal lobe. There is also the central sulcus, which is the divide between the frontal and parietal lobes, the parieto-occipital sulcus divides the parietal and occipital lobes, and the calcarine fissure which separates the cuneus from the lingual gyrus.

The focus of this article is on the cortex of the frontal lobe, the largest of the four, and in many ways the lobe which participates most in making us human. It is located at the most rostral (anterior) region of each cerebral hemisphere, separated from the parietal lobe by the central sulci and the temporal lobe by the lateral cerebral (Sylvian) fissure.[2] Particular regions of the frontal cortex are responsible for numerous capabilities, most notably the performance of motor tasks, judgment, abstract thinking, creativity, and maintaining social appropriateness.

Structure and Function

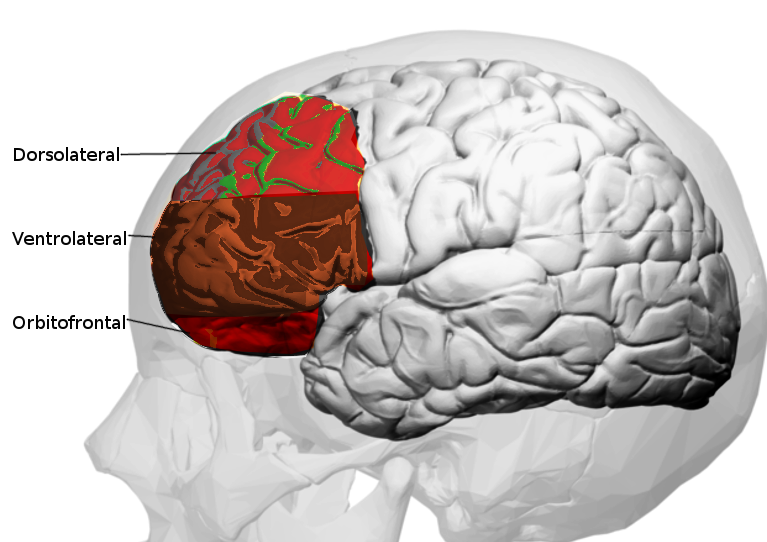

The frontal cortex contains four main gyri. The precentral gyrus, which is directly anterior to the central sulcus and runs parallel to it, contains the primary motor cortex (Brodmann area 4). The primary motor cortex is responsible for controlling the voluntary movements of specific body parts. Neuroanatomists and physiologists have developed a map known as the motor homunculus, which pairs particular regions of the primary motor cortex with the body part it controls. The most medial portion of the motor homunculus represents control of the lower extremities, the intermediate portion represents the upper extremities, and the most lateral represents control of the facial muscles. The pathway which originates in the primary motor cortex to control the extremities is the corticospinal tract, while the pathway that controls voluntary facial movement is the corticobulbar tract. Within the precentral gyrus and anterior to the primary motor cortex is the prefrontal cortex. The prefrontal cortex is known to be the higher-order association center of the brain as it is responsible for decision making, reasoning, personality expression, maintaining social appropriateness, and other complex cognitive behaviors.

Rostral to the precentral gyrus and running parallel with the central sulcus is the precentral sulcus. Extending forward and downward from the precentral sulcus are the superior and inferior frontal sulci, which act to divide the frontal lobe's lateral surface into the remaining three main gyri: the superior, middle, and inferior frontal gyri.[2] The functions of these three gyri are still a topic of intense investigation. Research has proven that the dominant (left) superior frontal gyrus is a key component in the neural network of working memory as well as spatial processing.[3] Research has shown that the nondominant (right) superior frontal gyrus is involved in impulse control and that its activation modulates inhibitory control and motor urgency.[4] Inferior to the superior frontal gyrus, and separated from it by the superior frontal sulcus, is the middle frontal gyrus. The dominant (left) middle frontal gyrus plays a key role in the development of literacy, while the nondominant (right) middle frontal gyrus is responsible for numeracy.[5] Within the caudal portion of the middle frontal gyrus, at the intersection with the precentral gyrus, is the frontal eye fields (Brodmann area 8). The frontal eye fields control saccadic eye movements, rapid, conjugate eye movements that allow the central vision to scan numerous details within a scene or image.[6] The inferior frontal gyrus is the lowest gyrus of the frontal lobe, separated from the middle frontal gyrus by the inferior frontal sulcus. The caudal portion of the dominant (left) inferior frontal gyrus contains Broca's area (Brodmann area 44 and 45), which is responsible for speech production.

Embryology

During the third week of development, the human embryo undergoes a process known as gastrulation. This developmental period is when the embryo divides into three primary germ cell layers: the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. The ectoderm layer, with the aid of the mesoderm layer, undergoes a process known as neurulation. Neurulation is the term given to the embryonic formation of the human nervous system, and therefore the frontal cortex.

Neurulation begins with the notochord, a portion of the mesoderm, sending signals to the overlying ectoderm. The portion of the ectoderm receiving signals from the notochord, known as the neuroectoderm, then uses these signals to fold and thicken, eventually forming the neural tube. The neural tube goes on to grow in two directions, cephalad and caudad, with the most cephalad region forming the adult frontal cortex. Brain development begins with the formation of three primary vesicles: the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. The forebrain then goes on to develop into two secondary vesicles: the telencephalon and diencephalon. The telencephalon later becomes the basal ganglia and cerebral hemispheres, and thus the frontal cortex.[7][8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The frontal cortex receives its blood supply from two branches of the internal carotid artery: the anterior cerebral arteries and the middle cerebral arteries. The superior and medial aspects of the cortex receive its supply from the smaller anterior cerebral artery. In comparison, the inferior and lateral aspects receive supply from the much larger middle cerebral artery. The left and right anterior cerebral arteries connect via a small vessel that runs between them, which is known as the anterior communicating artery. The anterior communicating artery is clinically crucial as it provides a collateral pathway for blood when the flow through one of the internal carotids is compromised.

Venous drainage of the cortex of the brain generally begins at the nearest large vein, and then to a sinus, before ultimately draining into the internal jugular vein. The superior cerebral vein course upward on the surface of the hemisphere, draining the top of the frontal cortex into the superior sagittal sinus. The inferior cerebral veins drain the bottom portion of the frontal cortex and either end in the superficial middle cerebral veins or the transverse sinus.[9]

Lymphatic drainage of the nervous system behaves in a way that is unlike anywhere else in the body. This unique lymphatic system has been recently discovered and has the name of the ‘glial-related lymphatic system’ or the ‘glymphatic system.’ In the glymphatic system, lymph drainage behaves in a pattern similar to the way in which cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) enters the brain parenchyma. In the frontal cortex, the anterior and middle cerebral arteries extend into pial arteries, which run through the subarachnoid and subpial spaces. They then dive deep into the brain parenchyma, where they transition into penetrating arterioles and create the Virchow-Robin perivascular space. Glial aquaporin 4 channels play an essential role in transporting the CSF fluid from the perivascular space into the deep brain parenchyma and allow interchange with interstitial fluid. Ultimately, the perivenous space collects this fluid and drains it into the cervical lymphatic system.[10]

Physiologic Variants

The left cerebral hemisphere is commonly described as the dominant hemisphere, while the right hemisphere is nondominant. This arrangement is true for most people as one’s dominant hemisphere is typically the opposite of their handedness. The majority of people are right-handed, and therefore, in most cases, the left cerebral hemisphere is dominant. Certain areas of the frontal cortex, such as Broca’s area, are described as being in the left hemisphere as it is a dominant hemisphere structure and so, theoretically, if one’s dominant hemisphere was on the right their Broca’s area could be as well.[7]

Clinical Significance

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), formerly known as Pick disease, is a neurodegenerative disorder involving the frontal and temporal cortex, sparing the parietal and occipital lobes. The histopathological findings that characteristically present in FTD include round aggregates of tau protein known as Pick bodies and ubiquitinated TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43). The clinical manifestations of FTD vary depending on the location of degeneration but often encompass prominent personality changes, disinhibited social behavior, aphasia, and can even be associated with motor neuron disease. The core spectrum of FTD disorders includes behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), non-fluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia, and semantic variant primary progressive aphasia.

FTD is one of the more common etiologies of early-onset dementia, with the mean age of symptom onset being 58 years old. Behavior variant FTD, the most common of the subtypes, typically presents with a dramatic change in personality and has is where the neurodegeneration occurs more heavily in the frontal lobe than the temporal lobe. Patients with bvFTD often demonstrate socially inappropriate behavior, apathy, loss of empathy, compulsive behavior, and hyperorality, or dietary changes.

FTD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease with no cure. Treatment of FTD aims at lessening the symptoms and includes drugs such as SSRIs, atypical antipsychotics, and atypical antidepressants.[11]

Cerebrovascular Disease

The cerebrovascular diseases often manifest in the frontal cortex. When an individual has a stroke, their presenting symptoms can clue physicians into where in the brain the ischemia is taking place, and what blood vessel could be occluded. If someone has sudden weakness in their upper extremity and face, then by referring to the motor homunculus, it can be determined that their stroke is occurring on the lateral and inferior portion of their primary motor cortex, a region supplied by the middle cerebral artery. Thus this is termed a middle cerebral artery stroke. Of note, the corticospinal and corticobulbar pathways both cross on their way to their lower motor neuron, and as such, the motor cortex is contralateral to the side it innervates. If someone had suffered from a left middle cerebral artery stroke, they would present with right upper extremity weakness and right facial drooping. Anterior cerebral artery strokes are significantly less common but present with weakness in the contralateral lower extremity.