[1]

Moras M, Lefevre SD, Ostuni MA. From Erythroblasts to Mature Red Blood Cells: Organelle Clearance in Mammals. Frontiers in physiology. 2017:8():1076. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01076. Epub 2017 Dec 19

[PubMed PMID: 29311991]

[2]

Santos Ad, Dantas LE, Traina F, Albuquerque DM, Chaim EA, Saad ST. Pyrimidine-5'-nucleotidase Campinas, a new mutation (p.R56G) in the NT5C3 gene associated with pyrimidine-5'-nucleotidase type I deficiency and influence of Gilbert's Syndrome on clinical expression. Blood cells, molecules & diseases. 2014 Dec:53(4):246-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.05.009. Epub 2014 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 25153905]

[3]

Meguro R, Asano Y, Odagiri S, Li C, Iwatsuki H, Shoumura K. Nonheme-iron histochemistry for light and electron microscopy: a historical, theoretical and technical review. Archives of histology and cytology. 2007 Apr:70(1):1-19

[PubMed PMID: 17558140]

[4]

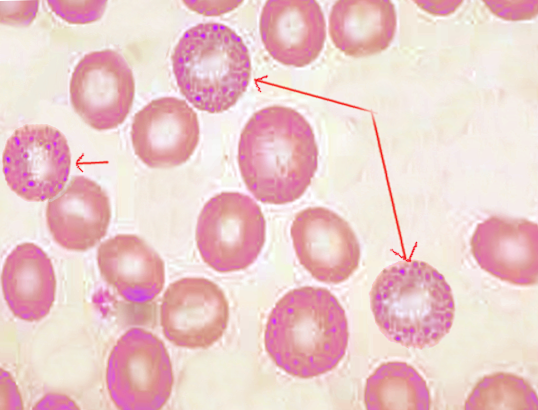

Chan NCN, Chan KP. Coarse basophilic stippling in lead poisoning. Blood. 2017 Jun 15:129(24):3270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-773499. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28620106]

[5]

JENSEN WN, MORENO GD, BESSIS MC. AN ELECTRON MICROSCOPIC DESCRIPTION OF BASOPHILIC STIPPLING IN RED CELLS. Blood. 1965 Jun:25():933-43

[PubMed PMID: 14294770]

[6]

Tsai MT, Huang SY, Cheng SY. Lead Poisoning Can Be Easily Misdiagnosed as Acute Porphyria and Nonspecific Abdominal Pain. Case reports in emergency medicine. 2017:2017():9050713. doi: 10.1155/2017/9050713. Epub 2017 May 29

[PubMed PMID: 28630774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[7]

Grasso IA, Blattner MR, Short T, Downs JW. Severe Systemic Lead Toxicity Resulting From Extra-Articular Retained Shrapnel Presenting as Jaundice and Hepatitis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Military medicine. 2017 Mar:182(3):e1843-e1848. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28290970]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Weiss D, Lee D, Feldman R, Smith KE. Severe lead toxicity attributed to bullet fragments retained in soft tissue. BMJ case reports. 2017 Mar 8:2017():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217351. Epub 2017 Mar 8

[PubMed PMID: 28275014]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[9]

Fakoor M, Akhgari M, Shafaroodi H. Lead Poisoning in Opium-Addicted Subjects, Its Correlation with Pyrimidine 5'-Nucleotidase Activity and Liver Function Tests. International journal of preventive medicine. 2019:10():36. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_490_18. Epub 2019 Mar 5

[PubMed PMID: 30967922]

[10]

Zhao Y, Lv J. Basophilic Stippling and Chronic Lead Poisoning. Turkish journal of haematology : official journal of Turkish Society of Haematology. 2018 Nov 13:35(4):298-299. doi: 10.4274/tjh.2018.0195. Epub 2018 Sep 5

[PubMed PMID: 30182925]

[11]

Vander Meeren S, Van Damme A, Jochmans K. Prominent basophilic stippling and hemochromatosis in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. International journal of hematology. 2015 Feb:101(2):112-3. doi: 10.1007/s12185-014-1716-6. Epub 2014 Dec 9

[PubMed PMID: 25487752]

[12]

Thom CS, Dickson CF, Gell DA, Weiss MJ. Hemoglobin variants: biochemical properties and clinical correlates. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2013 Mar 1:3(3):a011858. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011858. Epub 2013 Mar 1

[PubMed PMID: 23388674]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[13]

Zahid MF, Khan N, Pei J, Testa JR, Dulaimi E. Genomic imbalances in peripheral blood confirm the diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome in a patient presenting with non-immune hemolytic anemia. Leukemia research reports. 2016:5():23-6. doi: 10.1016/j.lrr.2016.05.001. Epub 2016 May 13

[PubMed PMID: 27298759]