Continuing Education Activity

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a group of rapidly growing disabilities. They are characterized by repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities, problems in social interactions. ASD is a complicated neurological disorder that is characterized by behavioral and psychological problems in children. These children become distressed when their surrounding environment is changed because their adaptive capabilities are minimal. This activity reviews the causes, presentation, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of child disintegrative disorder and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of child disintegrative disorder.

- Outline the physical exam of child disintegrative disorder.

- Review the treatment and management options available for child disintegrative disorder.

- Explain the interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication regarding the management of patients with child disintegrative disorder.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) encompasses a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disabilities. This spectrum is characterized by repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, activities, and problems in social interactions. ASD is a complicated neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by behavioral and psychological problems in children. These children become distressed when their surrounding environment is changed because their adaptive capabilities are minimal. The symptoms are present from early childhood and affect daily functioning. Children with ASD have co-occurring language problems, intellectual disabilities, and epilepsy at higher rates than the general population.

Childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD), also called disintegrative psychosis and Heller syndrome, is a rare disorder that is subsumed under ASD. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), childhood disintegrative disorder, along with other types of autism, is merged into a single spectrum called autism spectrum disorder. Childhood disintegrative disorder has a relatively late onset and is characterized by regression of previously acquired skills in the areas of social, language, and motor functioning. It is not known what causes this disease, and it is often seen that children who have this disorder have achieved normal developmental milestones before the regression of skills. The age at which this disease manifests is variable, but it is typically seen after three years of reaching normal milestones. The regression can be so fast that the child may be mindful of it, and in the beginning, may even ask what is going on with them. Some children may appear to be responding to hallucinations, but the most common and distinct feature of this disease is that the attained skills are gone.

Many children are already delayed when the disorder becomes apparent, but these delays are not always evident in young children. This condition has been described as a devastating disease that affects both the individual's life and the family.[1]

Etiology

The cause is still not known. The onset is variable. The development is insidious without a clearly demarcated onset. Children that have an autism spectrum disorder have an increased risk of having epilepsy, however, a causal correlation has not yet been identified.

One subtype of ASD, Childhood disintegrative disorder, is associated with the following diseases, particularly if it is late-onset:

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: A chronic infection of the brain by a form of the measles virus. This disease leads to the inflammation of the brain and the death of nerve cells.

- Tuberous sclerosis (TSC): A genetic disorder. Tumors formation in the brain, which is benign. It also affects other organs of the body like eyes, kidneys, heart, skin, and lungs.

- Leukodystrophy: In this condition, there is maldevelopment of the myelin sheath, causing white matter in the brain to disintegrate.

- Lipid storage diseases: Toxic accumulation of excessive fats (lipids) in the brain and nervous system

Epidemiology

According to some studies, ASD is becoming more prevalent. Whether this trend can be attributed to increased awareness, overdiagnosis, or overinclusive diagnostic criteria is yet to be identified. Its prevalence is reported to be 1 in 68. Childhood disintegrative disorder is a rare disease, with only 1.7 in 100,000 cases, and the prevalence of this disease is estimated to be 1 to 2 in 100,000.[2] Childhood disintegrative disorder is an uncommon disorder with a prevalence of 60 times less than that of autistic disorder.[3]

Pathophysiology

There is no clear-cut pathology of ASD however different populations have been suggested for different subtypes of ASD. For example, CDD occurs in children who have achieved normal developmental milestones, and this regression sometimes occurs very rapidly. This condition often develops abruptly and is most commonly seen in the fourth year of life, but there can be variation. Some consider it to be childhood dementia, indicating that the deposition of amyloid in the brain can be the possible cause of the disease, but this needs to be proven.[3][4]

History and Physical

The symptoms of ASD are usually identified by two years of age (specifically for CDD one-third of children experience regression of skills at the same time). Children with childhood disintegrative disorder generally have the worst outcome among individuals with ASD. Their cognitive and communication skills are affected. Most children with childhood disintegrative disorder experience a distinct prodrome characterized by bouts of anxiety and terror with no consistent medical, environmental, or psychosocial triggers.

A child affected with childhood disintegrative disorder shows normal development, and they normally develop age-appropriate verbal and nonverbal communication, as well as social relationships, motor, play, and self-care skills as compared to other same-aged children. However, by 2 to 10 years of age, they almost completely lose their acquired skills in 2 of the following 6 functional areas:

- Receptive language skills (comprehension of language: listening and understanding what is communicated)

- Expressive language skills (being able to produce speech and communicate a message)

- Social skills and self-care skills

- Bowel and bladder control

- Motor skills

- Play skills

Impairment of function also occurs in social interactions and communications.

The 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) Criteria for Childhood Disintegrative Disorder Diagnosis (WHO)

- Normal development up to the age of at least two years; the presence of normal age-appropriate milestones are achieved in the areas of communication, social relationships, play, and adaptive behavior at age two years or later are required for this diagnosis.

- A definite loss of previously acquired skills at the onset of the disorder. The diagnosis requires a clinically significant loss of skills (and not just a failure to use them in certain situations) in at least 2 of the following areas:

- Expressive or receptive language

- Play

- Social skills or adaptive behavior

- Bowel or bladder control

- Motor skills

- Qualitatively abnormal social functioning, manifests in at least 2 of the following areas:

- Qualitative abnormalities in reciprocal social interaction (of the type defined for autism)

- Qualitative abnormalities in communication (of the type defined for autism)

- Restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, including motor stereotypies and mannerisms

- General loss of interest in objects and the environment

- The disorder is not attributable to the other varieties of pervasive developmental disorder acquired aphasia with epilepsy, elective mutism, schizophrenia, and Rett syndrome.

Evaluation

Children diagnosed with childhood disintegrative disorder rarely reveal an underlying neurological or medical cause. Complete medical and neurological examinations are done, and tests to exclude reversible causes of the condition:

- Complete blood count

- Urea and electrolytes/glucose

- Liver function test

- Thyroid function test

- Heavy metal levels

- HIV testing

- Urine screening for aminoaciduria

- Neuroimaging studies (MRI or CT scan)

- Electroencephalogram (EEG)

These tests are usually done during the initial assessment in secondary care. Electroencephalogram (EEG) and neuroimaging studies are done to exclude the alternative diagnosis.

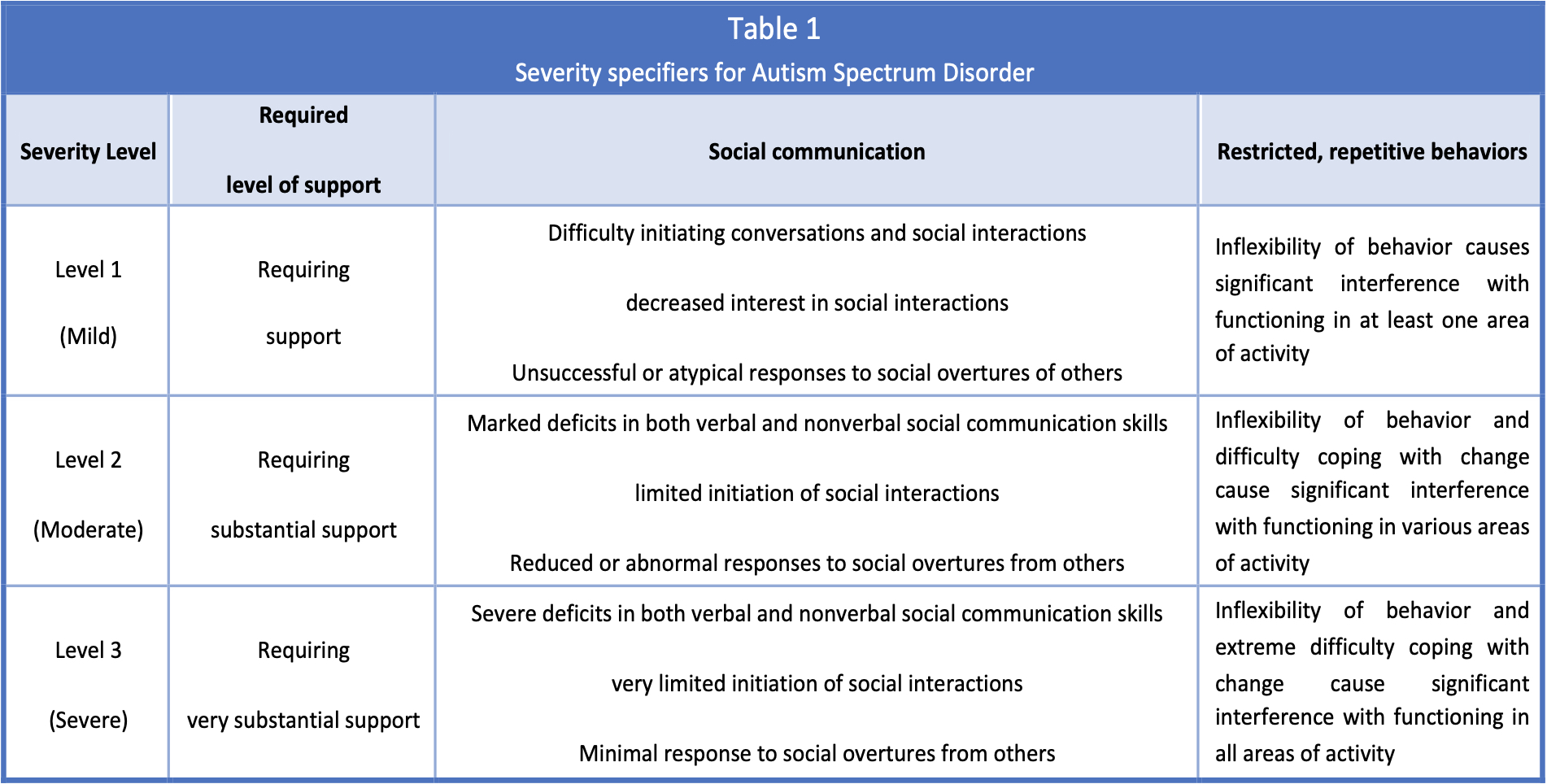

DSM V Criteria

- Deficits in social interaction and communication

- Restricted interests, repetitive behavior, and activities

- These symptoms impair everyday functioning

Treatment / Management

Treatment for childhood disintegrative disorder is similar to the treatment of autism. The stress falls on early and excessive educational interventions. Most of the treatment plan is behavior-based and highly structured. Family counseling, including educating the parents so that they can follow the child's treatments at home, is usually part of the overall treatment plan. Therapies in the areas of language, speech, social skills development, occupational, and sensory integration may all be used according to the needs of the individual child. Loss of language, skills related to social interaction, and self-care are delirious, and the affected children face ongoing problems in certain areas and require long-term care. Treatment of childhood disintegrative disorder requires behavior therapy, environmental therapy, and medications.

Behavior Therapy

The applied behavioral analysis mainly focuses on methodically training the patient to re-learn self-care, language, and social skills. These treatment programs are designed in such a way that they use a reward system to reinforce acceptable behaviors and discourage trouble behavior. These programs are usually devised by certified professionals in behavior analysis, which is then can be used by other healthcare personnel. People from different domains like speech therapists, physical therapists, psychologists, and occupational therapists with differing levels of competence can benefit from this. Teachers, parents, and caretakers are advised to use these behavior models at all times.

Environmental Therapy

In the form of sensory enrichment applies augmentation of the sensory experience to improve symptoms in autism, many of which are also present in childhood disintegrative disorder.

Medications

Medications are used to treat the symptoms as they develop during the disease as there is no drug available to cure this disease directly. Antipsychotic medications are used for repetitive behavior patterns and aggression. To control problematic behavior, particularly aggression, experts use selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), stimulants, and other antipsychotics. There is a significant risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome with the use of neuroleptic medication. If seizures develop, anticonvulsants are used.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes any of the other pervasive developmental disorders or causes of learning disability. Other specific diseases that need to be excluded are:

- Heavy metal poisoning (mercury and lead)

- Aminoacidurias

- Hypothyroidism

- Brain tumor

- Organophosphate exposure

- Seizure disorder (atypical)

- HIV infection

- Childhood schizophrenia

- Other rare conditions (glycogen storage disorders)

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Creutz-Jacob disease/new variant CJD

Prognosis

The prognosis of CDD is very poor, and the outcome is worse as compared with other subtypes of ASD. Once skills are lost, they usually do not return to normal. Only about 20% of children diagnosed with CDD can speak in sentences again. As adults, most patients with CDD remain dependent on full-time caregivers or are institutionalized. Around ten years of age, most of the skills are lost. There can be some but very restricted improvement seen in a few of the cases. Over the longitudinal course of the disease, children develop lifelong impairments of behavioral and intellectual functioning. The intellectual function, independence, and adaptive/adjusting skills are extremely affected, with most cases deteriorating to serious mental disability. Kids with this disease are dependent on caregivers for their entire life.[4]

Complications

Epilepsy commonly develops with the risk of seizures that increases throughout childhood with the highest seizure diathesis occurring during adolescence. SSRIs and neuroleptics can also the seizure threshold and thus must be used with caution. It has been previously reported that the life expectancy is normal, but mainly due to complications of epilepsy, the mortality of people with autistic spectrum disorders is two times that of the general population.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Parents and families who have children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder or other chronic diseases face many challenges. These challenges include social isolation, frustrations, strained relationships, and financial difficulties. Helpful strategies include encouraging families to tell their own stories, thus assisting with emotional processing. The focus should be on strengthening protective factors such as increasing parents' communication skills, behavioral management, and providing psycho-education for extending parents' understanding of their child's condition and developmental challenges. Other helpful strategies include connecting with others with the same disease, developing an alliance, caring for one's self, and become an advocate. Recommendations for health care providers include understanding the common problems faced by parents, building parent-to-parent connections, and encouraging a good relationship with parents and their children.[5][6]

Pearls and Other Issues

There is no treatment to cure autism spectrum disorder, but early diagnosis and early intensive management have the potential to produce favorable outcomes in all aspects of the disease. The screening tests should be carried out anytime during child development if there are concerns for autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. It is usually done at 18 and 24 months during well-baby visits. The overall basis for the management of autism spectrum disorder is 3-fold: (1) improve quality of life maximize function, (2) promote a child’s independence, and (3) maximize function.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Childhood disintegrative disorder under ASD is a very rare disease. The disorder is complex to manage and is best done with an interprofessional team that specializes in the management of childhood behavior disorders.

The main feature of this disease is that after achieving age-appropriate milestones, a child's previously acquired skills regress. Unlike autism, seizures are more frequently seen. The cause of this condition is not known, and there is no cure. It is important to recognize this disease and follow up with combined child pediatric and psychiatric assessments. Corticosteroid treatment seems to improve language, motor skills, and behavior in these children. It is important for primary care clinicians, including physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and physicians be familiar with this disease so that appropriate diagnosis and appropriate treatment can be obtained.[7][8] (Level 3)

Because many clinicians are not aware of childhood disintegrative disorder, they should seek advice from the Autism Society of America. Besides providing educational information, the society also provides legal assistance.

The school nurse should be actively involved in the care of these children as they have severe developmental disabilities and are vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse. Parents need to be educated about this disorder and be trained to recognize sexual abuse. The social worker should be involved to ensure that the home environment is safe and prevents the child from wandering away. Additionally, parents need to advise teachers to watch over their children while in school.

Finally, there is a problem with informed consent. Unless the issue is life-threatening, everyone involved in the care of the child should first get consent from the parent if an intervention is required. Not doing so can lead to unnecessary legal troubles.

Pharmacists should review medications, check the dosage, and review usage and side effects with parents. [Level 5]

Outcomes

The outcomes for these children are guarded, and the quality of life is very poor. Many succumb to illness and die prematurely.