Continuing Education Activity

Neuroacanthocytosis refers to a group of inherited genetic disorders resulting in a combination of misshapen red blood cells (acanthocytes) and progressive neurological decline. The neurological presentation can vary widely among diseases and can include shared characteristic features of movement disorders, neuropathy, psychiatric symptoms, neurocognitive degeneration, and seizures. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of neuroacanthocytosis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of neuroacanthocytosis.

- Review the appropriate evaluation of neuroacanthocytosis.

- Outline the treatment options available for neuroacanthocytosis.

- Summarize the importance of an interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care and improve outcomes for patients affected by neuroacanthocytosis.

Introduction

Neuroacanthocytosis refers to a group of inherited genetic disorders resulting in a combination of misshapen red blood cells (acanthocytes) and progressive neurological decline.[1] The neurological presentation can vary widely among diseases and can include shared characteristic features of movement disorders, neuropathy, psychiatric symptoms, neurocognitive degeneration, and seizures.[2] Specific diseases are many, including chorea-acanthocytosis (ChAc),[3] McLeod syndrome (MLS),[4] Huntington like-disease 2 (HDL2),[5] pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN, also known as Hallervorden Spatz disease),[6][7] HARP Syndrome (considered part of the PKAN spectrum consisting of hypoprebetalipoproteinemia, acanthocytosis, retinitis pigmentosa, and pallidal degeneration), abetalipoproteinemia (ABL),[8] hereditary hypobetalipoproteinemia (HHBL),[9] and aceruloplasminemia.[10][11] The two core conditions are chorea-acanthocytosis and McLeod Syndrome. Each neuroacanthocytosis disorder is extremely rare, with a prevalence of less than 1 to 3 per 1,000,000 individuals for PKAN or fewer than 100 cases ever reported in the case of ABL.

Etiology

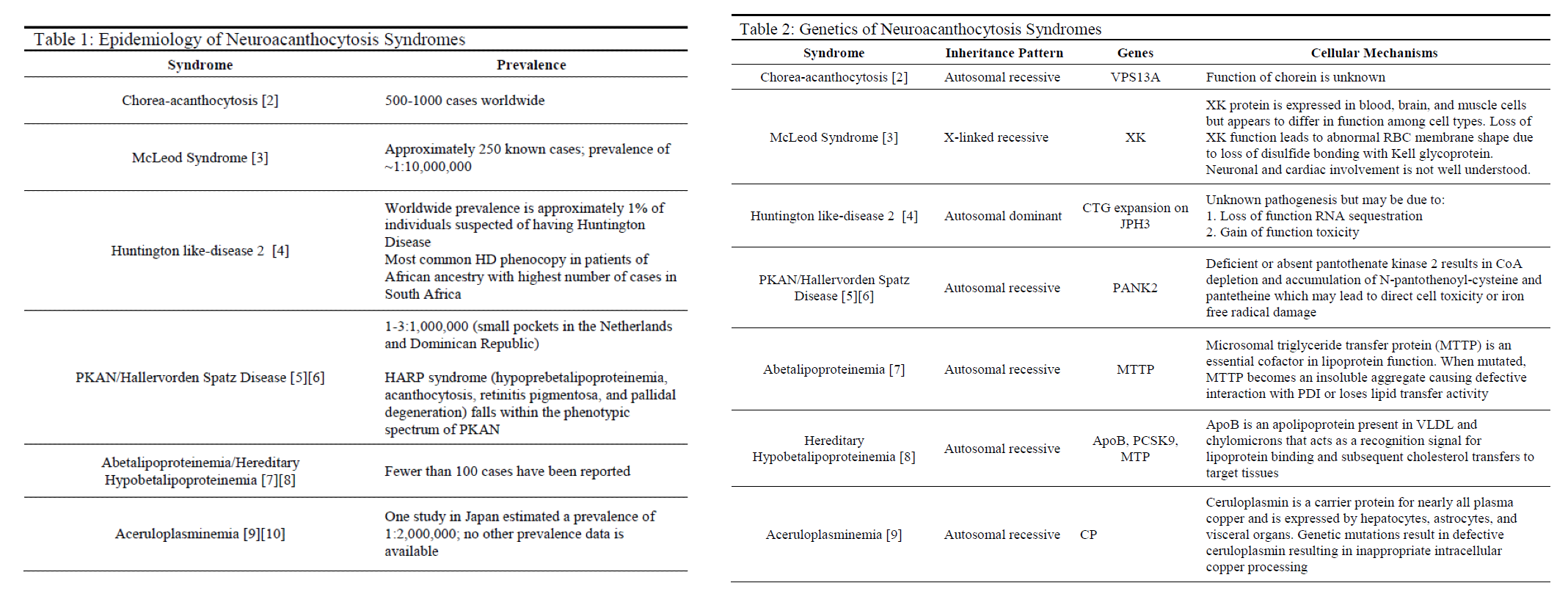

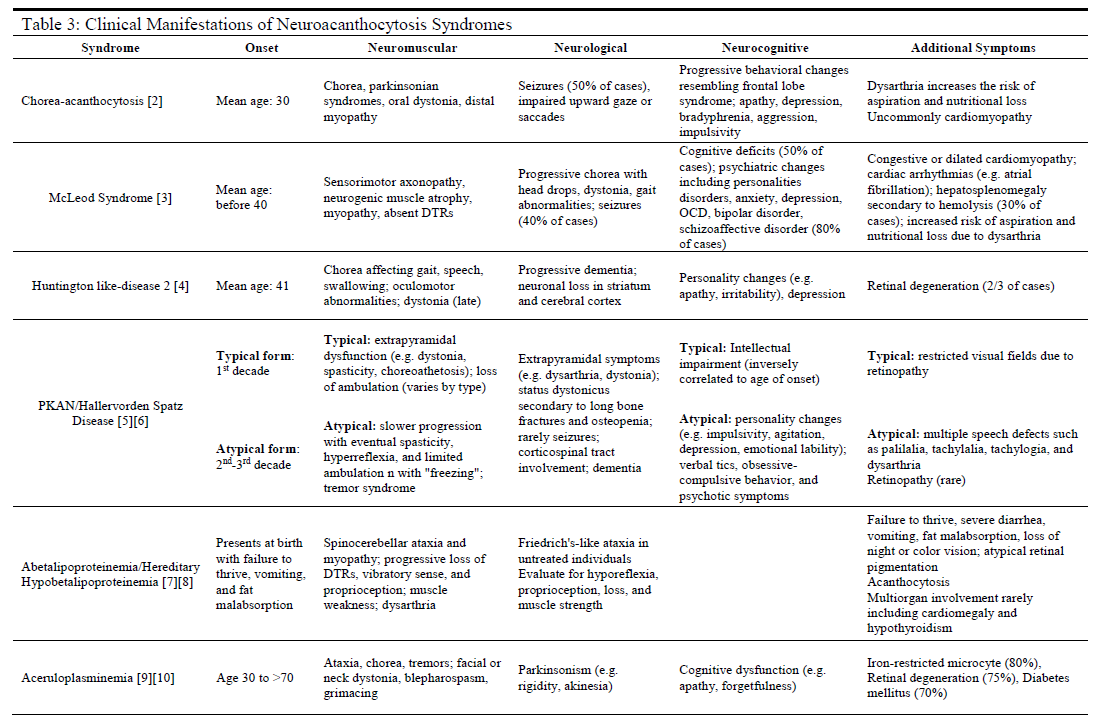

Neuroacanthocytosis syndromes are caused by a variety of genetic mutations that are inherited in several different patterns, with the most common being autosomal recessive (see Tables 1 & 2). Other syndromes such as McLeod syndrome are inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern, whereas Huntington like-disease 2 and hereditary hypobetalipoproteinemia are inherited in autosomal dominant and codominant patterns, respectively. HDL2 directly results from trinucleotide expansions of JPH3 very similarly to Huntington disease with patients experiencing intergenerational disease anticipation based on the extent of genetic expansion. Many of these diseases vary in genetic penetrance and phenotypic manifestations.[3][4][5][6][8][9][10]

Epidemiology

Each neuroacanthocytosis syndrome is exceedingly rare (see Table 1). Several populations have been identified as having higher prevalence compared to the global population. Examples include HDL2 demonstrating increased reported cases among individuals of African heritage and PKAN occurring more often in small pockets in the Netherlands and the Dominican Republic.[5]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of these syndromes is unique to each and can vary widely in phenotypic disease manifestation (see Table 2). The direct cellular mechanisms of several syndromes such as PKAN, aceruloplasminemia, and diseases of lipoproteins are understood and described in the current literature. These syndromes tend to have better outcomes either due to milder disease progression or treatment modalities that prevent significant mortality and morbidity.[6][8][9][10] Other diseases such as ChAc, MLS, and HDL2 are not well understood despite the identification of involved genes.[3][4][5] These diseases tend to be much more chronically debilitating and are not uniformly responsive to attempted treatments that have been sparsely reported.

History and Physical

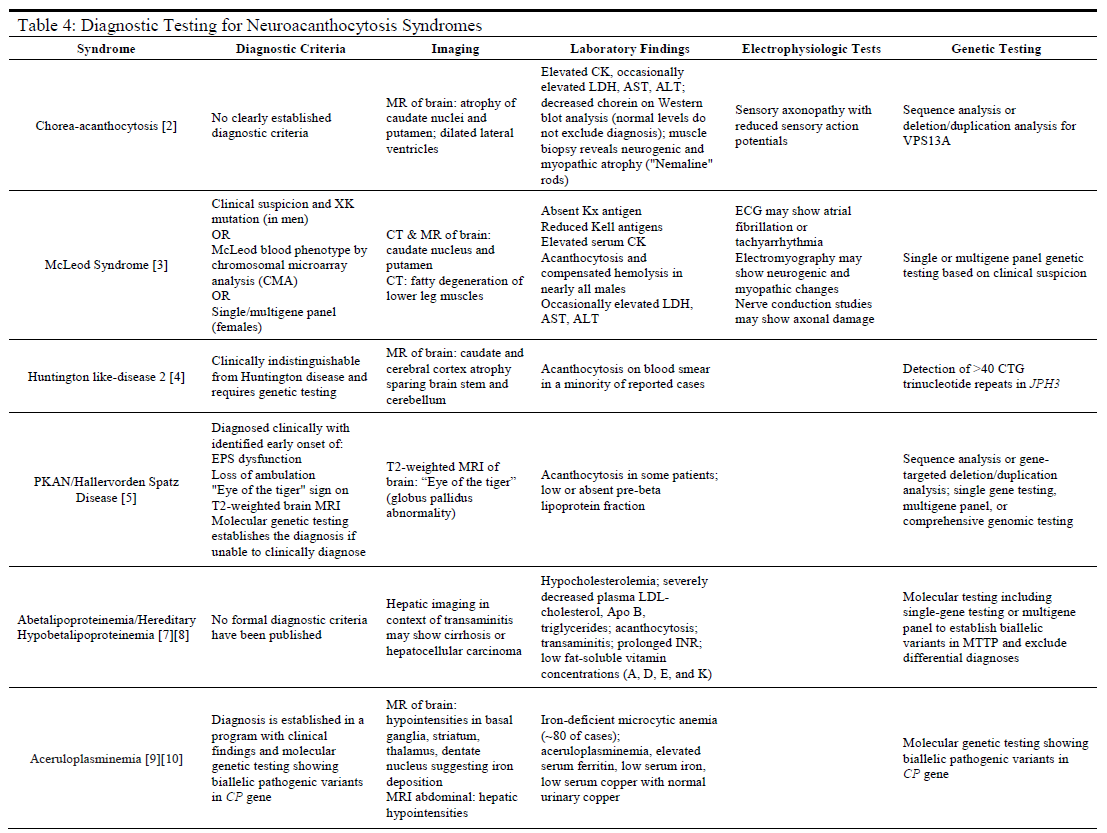

Nearly all patients affected by neuroacanthocytosis syndromes will experience the eventual onset of progressive abnormalities in movement (usually ataxia or hyperkinetic movements) with a neurocognitive decline and behavioral changes (see Table 3). Each specific disease, however, may present with symptoms and comorbidities unique to the disease. If the clinician possesses significant clinical suspicion of a neuroacanthocytosis syndrome, a thorough physical exam is required. This would include a complete physical and neurological examination, including reflexes, cranial nerves, gait, muscle strength, and mental status exams.

A clear history of progressive neurological, neuromuscular, or neuropsychiatric symptoms that are not consistent with other more common diseases plays an integral role in identifying these rare syndromes as possible diagnoses. The acquisition of prior records, family history, collateral history, and any prior genetic testing may prove instrumental in establishing accurate differential diagnoses and choosing clinically appropriate diagnostic modalities for further evaluation.

Evaluation

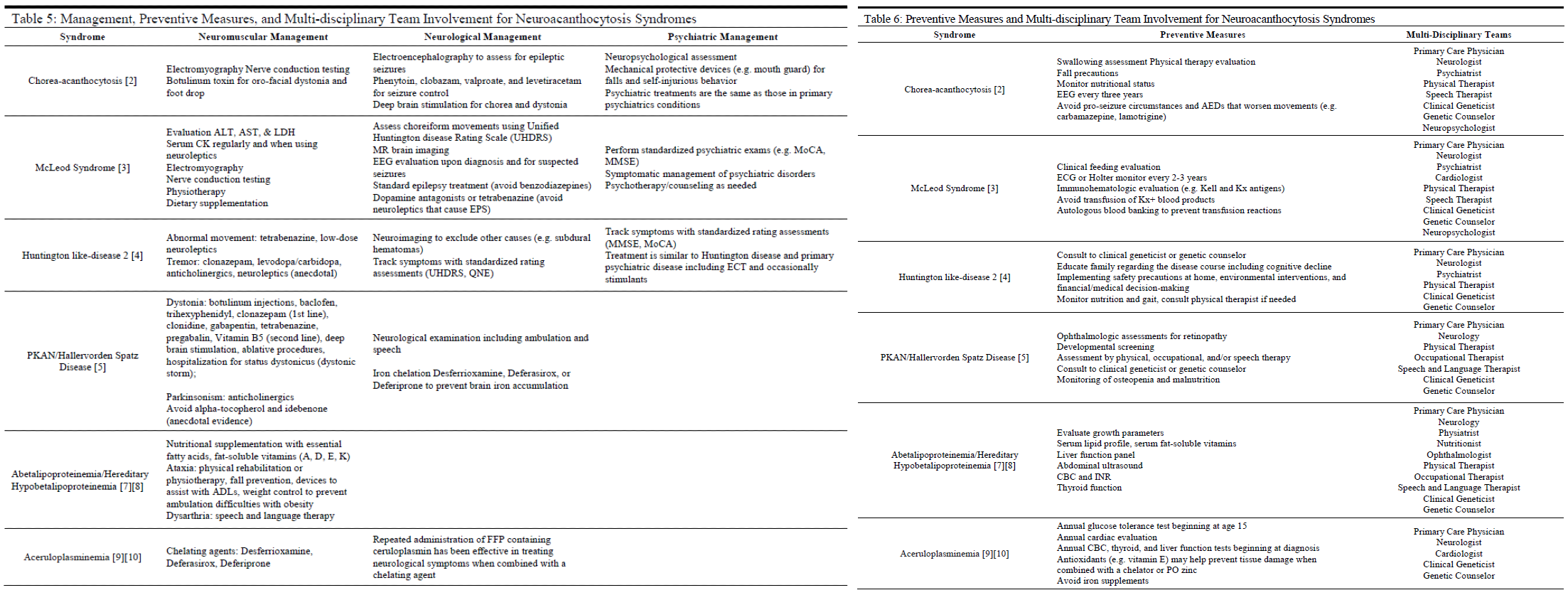

For many of these syndromes, the clinical symptoms will often prompt the use of additional diagnostic modalities that are instrumental in establishing a correct diagnosis (see Table 4). Such modalities include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) scans to assess neurological involvement in the cerebral or spinal nervous tissues. Additionally, laboratory testing of serum samples may be useful in ruling out some diseases while providing confirmatory data for others, as in the case of the diseases of lipoproteins (ABL and HHBL) or aceruloplasminemia. For most neuroacanthocytosis syndromes, there are either no clear diagnostic criteria (e.g., ChAc, ABL, and HHBL) or genetic testing to identify diseases that may otherwise be indistinguishable from other syndromes (e.g., HDL2).

Treatment / Management

There is no cure or definitive treatment for several of the neuroacanthocytosis syndromes, such as ChAc and MLS (see Table 5).[12] With the exception of ABL, HHBL, and aceruloplasminemia, the goals of management generally are to:

1) Treat symptomatically

2) Slow the development of progressive symptoms

3) Evaluate for and prevent where possible serious causes of morbidity and mortality such as ophthalmic involvement, metabolic/hormonal imbalances, seizures, cardiac involvement, and status dystonicus.

Interprofessional treatment teams have been advocated as the ideal approach in caring for patients who likely have complex and significant symptoms that run the gamut of neurological to psychiatric to multiple organ systems.[12]

Consultation by medical specialists in neurology, psychiatry, neuropsychiatry, ophthalmology, or clinical genetics may be appropriate in identifying, evaluating, and managing patients diagnosed with neuroacanthocytosis syndromes (see Table 6).

Differential Diagnosis

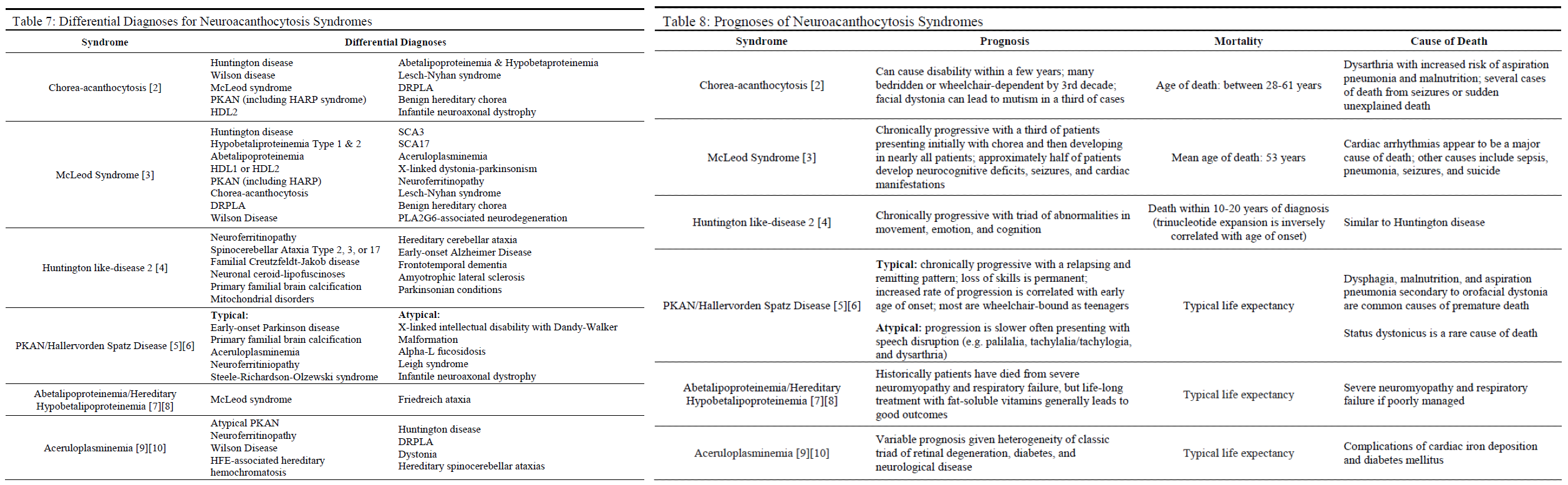

The differential diagnoses for these rare syndromes are many and sometimes may be indistinguishable from other disease entities without the appropriate radiological, laboratory, or genetic workup (see Table 7).

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Due to the extreme rarity of these syndromes, there have been no randomized control trials or experimental treatment studies assessing the efficacy of diagnostic or treatment modalities.[12][13][14] Information regarding diagnostic criteria and possible treatments have been largely developed from the aggregation of case reports and case series.[12]

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

There are several side effects to keep in mind for several specific syndromes and their associated management (see Table 5). For example, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) such as carbamazepine and lamotrigine should be avoided in patients with ChAc due to the worsening of involuntary movements.[3] Conversely, long-term use of benzodiazepines should be avoided as an AED in patients with McLeod syndrome due to potential negative effects on the neuromuscular system. Additionally, dopamine antagonists or tetrabenazine should be avoided due to increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) in MLS patients.[4]

Another consideration for MLS patients is to avoid heterologous blood product transfusions due to an increased risk of adverse transfusion reactions. Case reports have suggested avoiding alpha-tocopherol and idebenone in treating the neuromuscular symptoms of patients with PKAN due to anecdotal evidence suggesting worsening of symptoms.[6] Finally, patients should avoid iron supplementation or other sources of exogenous iron due to the iron accumulation inherent in the disease.[10]

Prognosis

The prognosis for these syndromes is variable. Syndromes such as ChAc, MLS, typical PKAN, and HDL2 are known to be chronic and progressive, often resulting in complications of dysarthria such as malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia with eventual death (see Table 8). In some cases, complicating symptoms such as seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and status dystonicus may cause premature death. On the other hand, the mortality and progression of aceruloplasminemia, ABL, and HHBL are heavily influenced by appropriate management with chelating agents and fat-soluble vitamin supplementation (respectively) with patients enjoying a typical lifespan if managed appropriately.[8][9][10]

Complications

Many of the complications arising from neuroacanthocytosis syndromes derive from neuromuscular deficits or neurocognitive decline (see Table 3). Neuromuscular symptoms such as chorea, ataxia, myopathy, dystonia, loss of dorsal column, or spinocerebellar spinal tracts can result in gait disturbances and inability to participate in ADLs. Additional progressive cognitive deficits or personality changes (including increased impulsivity, aggression, or psychiatric symptoms) can further complicate care for patients diagnosed with a neuroacanthocytosis syndrome. Several complications can be life-threatening, including seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, status dystonicus, and psychiatric comorbidities such as suicidality.

Ophthalmological complications such as retinal degeneration and retinopathy are commonly described in cases of PKAN, ABL, HHBL, and aceruloplasminemia. In the case of several metabolically driven diseases such as ABL, HHBL, and aceruloplasminemia, multiple organ systems can be involved resulting in anemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiomegaly, hepatosplenomegaly, and hypothyroidism.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Genetic counseling plays an important role in the management as well as appropriate evaluation and education for both the patient and involved family members. Consultation with a genetic counselor and clinical geneticist can provide important clinical information such as genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of the disease, possible disease progression, and the likelihood of disease occurring in relatives or offspring.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Recent literature advocates interprofessional team-based care as the ideal approach in caring for patients diagnosed with neuroacanthocytosis syndromes due to the severity and chronic progression of symptoms as well as possible development of severe medical comorbidity.[12] Such a care team would likely consist of the patient's primary care clinician, neurologist, clinical geneticist (or genetic counselor), and several other therapeutic modalities (see Table 5). Providers may seek additional care in consultation with specialists in psychiatry, ophthalmology, and cardiology in diseases such as MLS, PKAN, and ABL/HHBL. The extreme rarity of these syndromes significantly limits evidence-based treatments. Patients with these syndromes may require involved and prolonged team-based care to improve symptoms and prevent the development of serious medical complications.