Introduction

Mechanoreceptors are a type of somatosensory receptors which relay extracellular stimulus to intracellular signal transduction through mechanically gated ion channels. The external stimuli are usually in the form of touch, pressure, stretching, sound waves, and motion. Mechanoreceptors are present in the superficial as well as the deeper layer of skin and near bone. These receptors are either encapsulated or unencapsulated, and the free nerve endings are usually unencapsulated dendrite. There are four major categories of tactile mechanoreceptors: Merkel’s disks, Meissner’s corpuscles, Ruffini endings, and Pacinian corpuscles.[1]

Issues of Concern

Not much is known about the molecular actions that lead to tactile mechanoreceptor activation, which leads to subsequent signal transduction. Due to this lack of knowledge, it is difficult to modulate specific pathways of feel or pain through this mechanism.[2]

Cellular Level

Mechanoreceptors detect mechanical cues through mechanotransducer ion channels. Upon mechanical disruption of the receptor, ions can flow in or out of the cell, causing electrical depolarization. These depolarizations can result in the generation of action potentials. These action potentials propagate towards the central nervous system (CNS). Properties of molecules that cause mechanotransduction when exposed to mechanical forces are still not apparent.[3]

Development

Somatosensory neurons arise from neural crest cells. As the embryo grows from day 9.5 to 12.5, a subset of neural crest cells gives rise to somatosensory neurons that form pairs of dorsal root ganglions (DRGs) located in the intervertebral foramina for each spine level. The temporal waves of cell fate specification first establish the somatosensory neurons heterogeneity. All somatosensory neurons require the expression of neurogenin 1 or 2 (Ngn1/2). In early embryonic days (9.5 to 11.5 days), neurons express Ngn2 and include A-beta and A-delta afferents with large-diameter cell bodies and myelinated axons. These neurons will become either: low-threshold mechanoreceptors or proprioceptors. Transcription factors that specify mechanoreceptors include MafA and c-Maf. The thinking is that these factors enhance the specification of mechanosensory neurons by maintaining the expression of neurotrophin receptors Ret and Gfra2. Two weeks postnatal age, mechanoreceptive neurons are not fully mature, but several types of A afferents can be present in ex vivo electrophysiology preparations. This finding means mechanoreceptive neurons acquire a sensitivity to touch soon after specification but require postnatal maturation for adult physiological properties.[4]

Organ Systems Involved

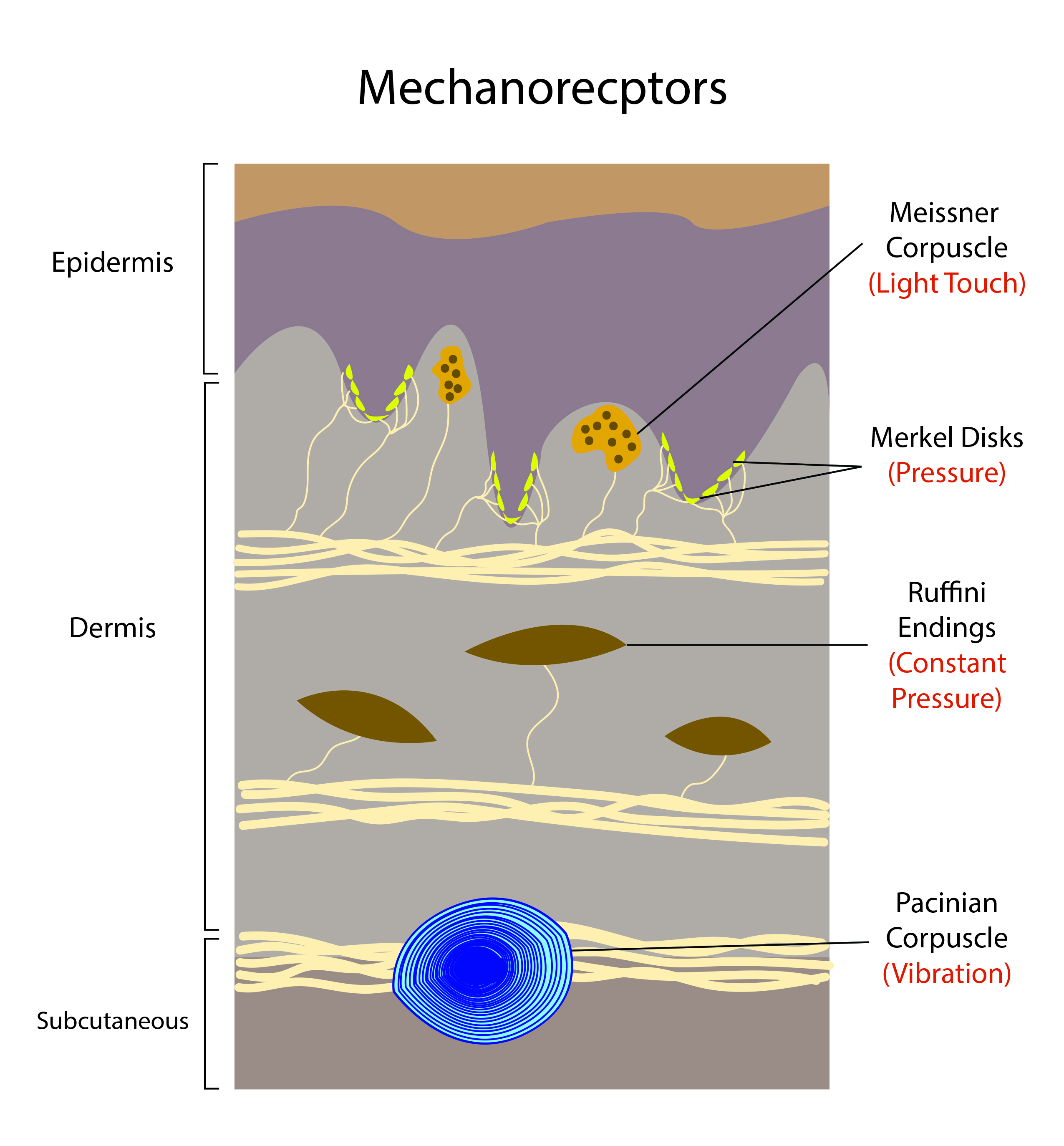

Tactile mechanoreceptors that respond to mechanical stimuli are in the skin[5][6][2][7][1]:

- Meissner’s corpuscles are encapsulated neurons between the dermal papillae under the epidermis of the glabrous skin on the fingers, palms, and soles - Meissner’s corpuscles are the most common mechanoreceptors of smooth and hairless skin.

- Pacinian corpuscles are large encapsulated nerve endings located in the subcutaneous tissue.

- They make up to 15% of the cutaneous receptors in the hand.

- Pacinian corpuscles are located in interosseous membranes, most likely to enable vibration detection in the skeleton.

- Merkel’s disks are unencapsulated nerve endings in the epidermis. They align with the papillae that lie under the dermal ridges; one-fourth of these mechanoreceptors are in the hand. There is a high density in the fingertips, lips, and external genitalia.

- Merkle discs are responsible for the fingerprint pattern of hands and feet.

- A cluster of Merkel disks in glabrous skin are referred to as “touch spots.” In hairy skin, these clusters are referred to as “touch domes.”

- Ruffini’s corpuscles slow-adapting, encapsulated mechanoreceptors deep in the skin, ligaments, and tendons - they account for 20% of the receptors in the human hand.

Baroreceptors are near the arch of the aorta where the common carotid artery bifurcates. Afferent fibers from these baroreceptors join the ninth cranial nerve, which travels to the nucleus of the solitary tract within the dorsal medulla. Baroreceptors also project to efferent cardiovascular neurons in the spinal cord and medulla. There are stretch receptors in the lung and heart vessels known as cardiopulmonary receptors. These receptors transmit afferent signaling through the vagus nerves. The efferent part consists of sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers towards the heart, vascular smooth muscles, and other organs.[8]

Function

Tactile mechanoreceptors enable touch, an essential sense for the survival and development of humans. Contact with objects provides information to the CNS that allows exploration of the environment[3]:

- Meissner corpuscles are involved in skin movement and object handling detection, and their primary stimulation is through dynamic deformation.

- Ruffini corpuscles primarily sense skin stretching, movement, and finger position.

- Pacinian corpuscles sense vibrations and detect fine textures.

Afferent signals from baroreceptors contribute to a negative feedback loop within the medulla responsible for mean arterial pressure (MAP) maintenance. A rise in MAP causes activation of the baroreceptor, resulting in a reduction of sympathetic signals to vessels and the heart. This signal modification reestablishes MAP to appropriate levels. Reduction in MAP consequently leads to a reduction in stimulation of baroreceptors, causing an increase in sympathetic stimulation, increased cardiac output, and vasoconstriction. This interaction is the baroreceptor reflex.[8]

Mechanism

For tactile receptors used for touch, there is precise coding of mechanical information. Mechanoreceptors will respond to vibrations, indentations of the skin, or movement of hair follicles.[2] Cutaneous mechanoreceptors localize in different layers of the skin with varying ranges of mechanical stimuli detection. This range sensing divides into two groups: low-threshold mechanoreceptors (LTMRs) and high-threshold mechanoreceptors (HTMRs). LTMRs react to light, benign pressure, while HTMRs react to stronger, harmful, mechanical pressure. Both mechanoreceptor types reside in DRGs and cranial sensory ganglia. Nerves associated with these two mechanoreceptor types classify as A-beta-, A-delta- or C-fibers based on their action potential conduction velocities.[3]

When tactical mechanoreceptors activate, there is an elevated frequency of action potential propagation, but after repeated stimulation, the cell will adapt to baseline electrical propagation. A-beta mechanoreceptors subclassify into two groups based on this phenomenon: rapidly adapting (RA) or slowly adapting (SA). Meissner's corpuscles and Pacinian corpuscles are rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors, while Merkel cells and Ruffini corpuscles are the SA mechanoreceptors. We can further divide RA and SA into subgroups. RA type 1 (RA 1) has smaller, more defined receptive fields and responds to the lower frequencies of vibration. RA 2 is the opposite, with larger receptive fields and responds to higher frequencies. SA 1 demonstrates a continual response to static stimulation along with small receptive fields. While SA 2 also produces consistent responses to the static stimulation and has larger receptive fields. SA 1 receptors are Merkel disks, SA 2 receptors are Ruffini corpuscles, RA 1 involves multiple Meissner corpuscles, and RA 2 receptors are Pacinian corpuscles.[2]

Baroreceptors are known as stretch mechanoreceptors. When pressure is low, baroreceptors are inactive, but when blood pressure increases, the aortic and carotid sinuses stretch further, leading to the activation of baroreceptors. More significant stretches lead to rapidly fired action potentials in baroreceptors. Baroreceptor action potentials travel to the solitary nucleus (SN), embedded within the medulla oblongata. The frequency of action potentials serves as a measure of blood pressure. Increased activation of the SN causes inhibition of the vasomotor center and stimulates vagal nuclei, which ultimately results in the inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system and the activation of the parasympathetic system.[9]

Related Testing

The two-point threshold test measures touch acuity, which refers to the ability to discriminate between touch stimuli. Touch acuity is routinely tested in neurology to assess the state of the dorsal column system. Mechanoreceptors in the skin are not uniform. Sensitive areas of the skin like the lips or skin have densely packed mechanoreceptors, while insensitive areas like the back have more sparse mechanoreceptors. This difference translates to sensitive regions of the body having a greater dedication to sensory processing in the primary sensory cortex compared to insensitive areas.[10]

Pathophysiology

There are many pathologies related to mechanoreceptors:

Mechanical Allodynia

Mechanical allodynia is a painful sensation caused by innocuous stimuli like a light touch. Essentially there is a shift in pain thresholds, causing normal stimuli to feel painful. RA neurons that participate in proprioception and touch have a low activation threshold with quick inactivation, which is consistent with a slow response to mechanical stimuli. Mechanonociceptors show a mixture of rapid, intermediate, and slow adapting currents accompanied by greater activation thresholds. It also appears that there is an alteration of CNS processing of normal input from ABeta LTMRs.[11][12][13]

Dyspnea

Dyspnea or shortness of breath is the most common accompaniment of lung disease. Dyspnea involves central, peripheral, chemoreceptor, and mechanoreceptor mechanisms. Muscle spindles in the respiratory muscle operate as mechanoreceptors. The receptors can detect muscle tension and innervate via the anterior horn cells in the spinal neurons, which project to the somatosensory cortex. Vibrations of the chest wall have been investigated to understand the mechanoreceptor’s role. In-phase chest wall vibrations, e.g., expiratory muscles vibration during expiration and inspiratory muscles vibration during inspiration, results in a decrease of dyspnea in control subjects along with subjects with COPD, while vibrations that are not in-phase increase dyspnea. These results show that mechanoreceptors in the chest wall innervated by the spinal neurons have a modulating effect on dyspnea.[14][12]

Clinical Significance

Mechanoreceptors are an important receptor class for the somatosensory system. These receptors have a well-known role in tactile feedback from the skin and skeletal system, which is essential for human development and sensation. The variety of tactile mechanoreceptors within the skin allow for differential detection of touch and vibrational stimuli that permit detection of benign or harmful pressure. Disease pathologies connected to mechanoreceptors often link to dysregulation of the neuromuscular signaling, which can lead to issues related to functional instability of anterior cruciate ligament, dyspnea, or pain. There is still a need for research regarding the molecular interactions that lead to mechanotransduction.