Continuing Education Activity

Somatic dysfunctions cause pain and suboptimal muscle function. The pelvis, a crucial structural and functional component of the musculoskeletal system, is pivotal in maintaining overall biomechanical balance. This sturdy, bony structure contains various muscles that allow the upper and lower body to function as one. Recognizing the interconnectedness of the body's systems, osteopathic practitioners employ the muscle energy procedure to assess and address pelvic dysfunctions with a hands-on, patient-tailored approach.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learners' competence in using the muscle energy procedure in evaluating and managing pelvic dysfunctions. This activity is also designed to equip learners to collaborate effectively with an interprofessional team caring for patients with pelvic dysfunction.

Objectives:

Identify the signs and symptoms indicative of pelvic somatic dysfunction.

Determine a diagnostic plan for evaluating individuals with somatic pelvic dysfunction.

Compare the different pelvic somatic dysfunction treatment options and develop a personalized plan for a patient with the condition.

Coordinate with an interprofessional team managing patients with pelvic dysfunction, formulating short- and long-term care plans to improve outcomes.

Introduction

The pelvis is composed of various ligaments, muscles, bones, and other structures that connect the axial skeleton to the lower extremities. Pelvic dysfunctions cause muscle pain, gait abnormalities, and viscerosomatic disturbances. Irritable bowel syndrome is a common functional problem that may arise from either a nerve disturbance or psychosomatic issues.[1]

Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) is a direct technique engaging and stretching the targeted muscles toward their restrictive barrier. The muscle energy (ME) procedure requires patient participation and, thus, clear patient-physician communication. ME effectively treats pain in various body areas, from the pelvis to the elbow and neck.[2] Understanding the proper application of this procedure enables providers to treat muscular and non-muscular pelvic pain.

Anatomy and Physiology

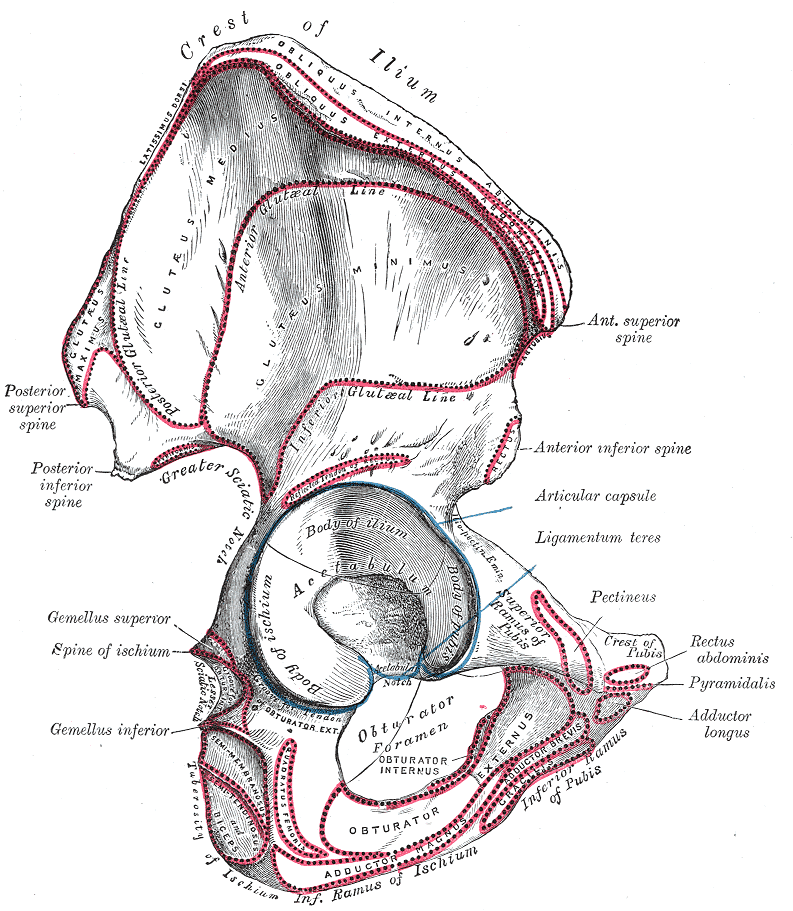

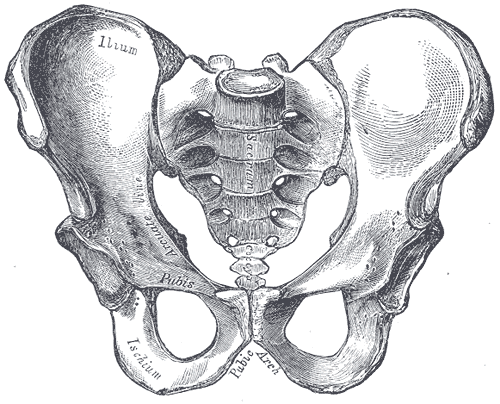

The pelvis' main function is to transmit weight from the torso to the lower body when sitting, standing upright, or ambulating (see Image. Hip Anatomy).[3] The pelvic girdle is a basin-shaped bone consolidation comprised of the ilium, ischium, and pubis (see Image. Male Pelvis Anatomy).

The ilium is the fan-shaped, superior hip bone. The ilium alae (wings) are the fan-like projections, while the ilium's body resembles a fan's handle. The body of the ilium comprises part of the acetabulum. The iliac crest occupies the ilium's superior edge. The iliac crest curves anteriorly to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), superiorly to the internal lip of the iliac crest, and posteriorly to the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). The iliac fossa is the anteromedial concave surface of the iliac alae. The ilium articulates posteriorly with the sacrum via its sacropelvic surface and the iliac tuberosity.

The ischium occupies the inferoposterior region of the pelvic girdle. The ischial body forms part of the acetabulum. The ischial ramus comprises part of the obturator foramen. The ischial tuberosity is a large posteroinferior projection of this bone, while the ischial spine is a smaller posteromedial protrusion. The lesser sciatic notch is the small recession between the ischial spine and tuberosity, while the larger furrow between the ischial spine and ilium posteriorly is the greater sciatic notch.

The anteriorinferior pubis has superior and inferior rami. The superior ramus occupies part of the acetabulum, while the inferior ramus helps form the obturator foramen. The pubic crest is the anterior thickening on the pubic body that continues laterally with the pubic tubercle. The pectineal line of the pubis (pecten pubis) is an inclined ridge on the lateral aspect of the superior pubic ramus.

The pelvic inlet divides the pelvis into the lesser (true) and greater (false) pelves. The pelvic brim is the bony region bordering the pelvic inlet. The right and left ischiopubic rami, which articulate at the pubic symphysis, comprise the pubic arch.

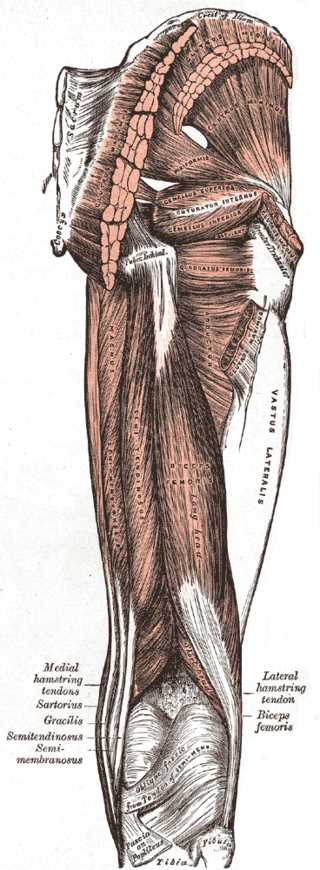

Pelvic muscles are involved in somatic dysfunctions in the area (see Image. Muscles of the Hip and Thigh). The main pelvic flexors include the iliacus, psoas, and rectus femoris, all receiving blood from the abdominal aorta and femoral artery [4]. Hip flexor injury is a common cause of acute groin pain.[5] The lumbar plexus innervates the iliacus and psoas, while the femoral nerve innervates the rectus femoris.[6]

The gluteus maximus is the primary pelvic extensor, supplied by the inferior and superior gluteal arteries and innervated by the inferior gluteal nerve.[7] The hip adductors include the pectineus and adductor magnus, longus, and brevis. The obturator artery supplies the thigh adductor compartment, which originates from the internal iliac artery.[8] Branches of the lumbar and sacral plexuses innervate the hip adductors.

The hip abductors include the gluteus minimus and medius and tensor fascia lata. These muscles are supplied mostly by the superior gluteal artery, with minor branches from the inferior gluteal artery.[9] The superior gluteal nerve innervates the hip abductors.[10] The hip abductors are vital to pelvic function and stability and proper ambulation.[11]

Indications

OMT's indications include pain in the following regions:

- Sacroiliac

- Hip

- Groin

- Lower back

- Leg

- Pelvic girdle [12]

Physicians widely practice ME for pelvic dysfunction management because of its safety and effectiveness. However, the technique requires patient participation in the treatment process.

Contraindications

OMT is generally safe, involving only minimal risks. ME should not be used if muscle contraction causes severe pain or the patient has local fractures and unstable joints. Recent surgery is also a contraindication.

Equipment

Equipment needed for this procedure includes an OMT table and stool. OMT tables and stools have different features enabling the proper execution of the technique. The choice of equipment depends on individual treatment styles and clinic requirements.

Personnel

Only the clinician is required to perform ME.

Preparation

The physician should discuss the procedure's risks and benefits with the patient before the session. Additionally, the patient's pain severity must be assessed before the session as a baseline for posttreatment comparison.

Technique or Treatment

The patient must be evaluated for pubic dysfunction before treating the pelvis. However, the physician must ask for permission before examining this sensitive area. When examining the pubis, the patient is placed supine with the legs extended. The physician places the heel of the hand inferior to the umbilicus, palpating caudally until the pubic symphysis is located. Once located, pubic evenness may be assessed by placing an index finger on each side of the symphysis, pressing caudally, and assessing the pubic bones visually. Pubic tenderness and alignment must be established.

To begin the muscle energy procedure, the patient must bend their knees to at least 90°. Afterward, the patient must place their ankles together and allow the knees to fall laterally. The physician then gently pushes a fist or full forearm between the knees and asks the patient to adduct the legs against force. The knees are held together for 3 counts before relaxing. Afterward, the physician holds the patient's knees together. The physician then wraps their arms around the patient's knees, instructing them to abduct against resistance for 3 counts. The treatment is complete if articulation is heard. Otherwise, the treatment must be repeated 2 more times. Afterward, the patient is asked to briefly raise and then lower their buttocks in a bridge, allowing the pelvis to reset. The pubic symphysis should be reexamined for evenness. The treatment must be repeated if this area is lopsided.

The characteristics of pelvic dysfunction that must be identified before treatment are laterality, ASIS and PSIS orientation, inflare or outflare, and superior innominate shear. Proper identification allows for the osteopathic technique's effective execution.

The tests that can determine laterality are the standing flexion and ASIS compression tests. In the standing flexion test, the patient must be standing and facing away from the physician. The physician then places both thumbs on the patient's PSIS and asks them to bend forward slowly. Laterality is determined by which side the PSIS travels a greater distance relative to its original position. The sacroiliac joint on that side is dysfunctional. The patient's hamstrings must be stretched before doing this test because tight hamstrings could lead to a false negative and not allow the dysfunctional sacroiliac joint to rise.

Meanwhile, the ASIS compression test is performed while the patient is supine. The physician places both hands on the patient's right and left ASIS, applying pressure to these areas in a rocking motion one side at a time. The side that shows greater resistance has a positive ASIS compression test. After determining laterality, the physician must compare the ASIS and PSIS orientation on both sides.

The laterality test should be positive on the left in patients with a left anterior rotation. The left ASIS would then be lower than the right ASIS, while the left PSIS would be higher than the right PSIS. To treat a left anterior rotation, the patient should lie supine on the table, with the physician flexing the patient's left knee and hip until a barrier is met. The physician will then hold this position and provide isometric force while the patient pushes against the physician with their hip extensors for 3 to 5 seconds. The physician then flexes the hip against another restrictive barrier, repeating the process 2 to 4 more times or until the restrictive barriers disappear. The ASIS and PSIS heights are then assessed to confirm the resolution of the somatic dysfunction.

In patients with a left posterior rotation, the laterality test should be positive on the left. The left ASIS would then be higher than the right ASIS, while the left PSIS would be lower than the right PSIS. To treat a left posterior rotation, the patient is asked to lie supine. The physician then drops the patient's left leg off the table and pushes down the knee until it encounters a barrier. The physician then holds this position and provides isometric force while the patient pushes back with their hip flexors for 3 to 5 seconds. Afterward, the physician extends the patient's hip toward a new restrictive barrier. The whole process is repeated 2 to 4 more times or until the restrictive barriers disappear. The physician re-examines the ASIS and PSIS heights at the end of the treatment to confirm the resolution of the dysfunction.

An inflare exists when the ASIS is closer to the midline and the PSIS moves away from the midline. The reverse is true for an outflare. Physicians should use the umbilicus as a landmark to determine the ASIS and PSIS distance from the midline.

Patients with a left inflare have the laterality test positive on the left. The left ASIS is then closer to the midline than the right ASIS, while the left PSIS is farther from the midline than the right PSIS. To treat a left inflare, the patient is asked to lie supine, with the left lower extremity in a "figure four" position. The physician then pushes towards the ground on the patient's knee until they feel a restrictive barrier. The patient will then push upwards against the physician using the adductors for 3 to 5 seconds. Afterward, the physician pushes down on the patient's knee again until another restrictive barrier is felt. The process is repeated 2 to 4 times or until no more restrictive barrier is appreciated. The physician will assess the ASIS and PSIS heights after the treatment to determine if the somatic dysfunction has resolved.

Meanwhile, patients with a left outflare will have a positive laterality test on the left. The left ASIS would thus be farther from the midline than the right ASIS. The left PSIS would be closer to the midline than the right PSIS. To treat a left outflare, the patient must lie supine and flex their hip to 90°. The physician then pushes the patient's knee medially until they feel a restrictive barrier. Then, the patient will push against the physician for 3 to 5 seconds using their abductors. Afterward, the physician flexes the patient's hip to 90° again and pushes the knee medially to the new restrictive barrier. The process is repeated 2 to 4 times more or until the restrictive barrier disappears. At the end of the session, the physician examines the ASIS and PSIS heights to confirm the resolution of the somatic dysfunction.

A superior innominate shear occurs when the ASIS and PSIS on one side are superior to their contralateral counterparts. Treatments for this dysfunction do not involve ME techniques, though the condition is diagnosed similarly.

Patients with a left superior shear will have a positive left laterality test. Thus, the left ASIS is higher than the right ASIS, and the left PSIS is higher than the right ASIS. To treat a left superior shear, the patient must lie supine, holding firmly onto the table. The physician then grasps the patient's left ankle with both hands while adding traction and slight internal rotation. Next, the patient takes a deep breath in, and on exhalation, the physician pulls quickly and firmly on the ankle caudad. This technique is called "high velocity, low amplitude" (HVLA). Afterward, the physician reassesses the ASIS and PSIS heights to determine that somatic dysfunction has resolved.

Patients with a left inferior shear also have a positive laterality test on the left. The left ASIS is lower than the right, and the left PSIS is lower than the right. To treat a left inferior shear, the patient must hop on their left leg for 10 to 15 seconds. The physician will then examine the ASIS and PSIS heights to determine somatic dysfunction resolution.

The techniques explained above are described only for one side of the pelvis. However, these techniques apply to either side of the innominate bone.

Complications

The physician should warn the patient of posttreatment soreness that may last 24 to 72 hours. Staying well-hydrated, resting, and using ice or heat packs on the treated area may help alleviate this symptom.

Clinical Significance

Pelvic somatic dysfunctions can manifest in various ways. Groin and lower back pain are the most concerning symptoms, as these manifestations may start unnecessary medications or require imaging and invasive procedures. OMT can be performed in the office by any osteopathic physician. The provider can save patients time and money and improve their quality of life if properly trained to recognize these dysfunctions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

OMT is typically only performed by the osteopathic physician. However, medical and osteopathic doctors must collaborate to educate patients about cost-effective and safe treatments, especially in cases where neither surgery nor medications are suitable. Medical doctors should thus help patients understand that OMT can relieve various forms of pelvic dysfunction more effectively than conventional treatments. This modality provides a non-invasive alternative that can benefit patients.