Introduction

The larynx is a midline structure at the level of C3 through C6 that connects the pharynx to the trachea. Its major functions include respiration, phonation, and swallowing. It is comprised of a cartilaginous skeleton, muscles, mucosal lining, ligaments, and membranes.[1]

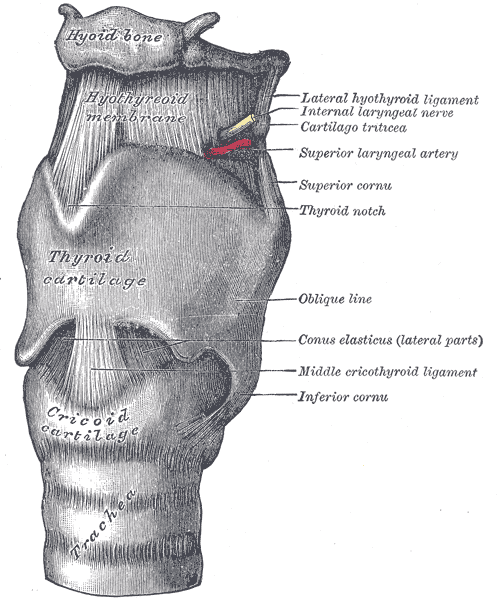

The thyrohyoid membrane is one of the extrinsic membranes that compose the larynx. It is a broad fibro-elastic layer named for its attachments as it attaches the upper border of the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone. The thicker median section of the membrane is the thyrohyoid ligament. It attaches the superior thyroid notch/laryngeal notch to the hyoid. The lateral surfaces of the membrane contain an aperture for the internal branches of the superior laryngeal nerves, the superior laryngeal artery, and lymphatics.

Structure and Function

The normal swallowing mechanism includes laryngeal elevation, posterior deflection of the epiglottis, inhibition of respiration, and closure of the vocal cords to prevent aspiration.[2]

The thyrohyoid membrane connects the thyroid cartilage to the hyoid bone and facilitates the superior movement of the larynx during swallowing. It is separated from the hyoid body by a bursa that facilitates this upward movement during swallowing.

The thyrohyoid membrane also provides cranial support and suspension.[3]

Embryology

The lower respiratory system begins its development during the fourth week as an outgrowth of the ventral wall of the foregut, also known as the respiratory diverticulum. The endodermal lining of the respiratory diverticulum gives rise to the epithelial lining of the trachea, bronchi, alveoli, and larynx.

The cartilaginous and muscular components of the larynx, including the thyrohyoid membrane, are derived from the fourth and sixth pairs of pharyngeal arches. The superior laryngeal nerve (a branch of CN X) supplies the part of the larynx that develops from the fourth pharyngeal arch, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve (a branch of CN X) supplies the part that derives from the sixth pharyngeal arch.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superior and inferior laryngeal arteries supply most of the blood to the larynx.

The superior laryngeal artery is a branch of the superior thyroid artery near its bifurcation from the external carotid artery. It enters the larynx with the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve through the aperture of the thyrohyoid membrane. It supplies blood to the muscles, mucous membrane, and glands of the larynx, and will anastomose with the superior laryngeal artery from the opposite side.

The inferior laryngeal artery starts at the inferior thyroid branch of the thyrocervical trunk, a branch of the subclavian artery. It ascends into the larynx along with the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve.[1]

The lymphatic system of the larynx can be differentiated based on if draining from above or below the vocal folds:

- Lymph drainage from above the vocal folds travels along the superior laryngeal artery, passing through the foramen in the thyrohyoid membrane, and drain into the deep cervical lymph nodes at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery.

- Lymph drainage from below the vocal folds travels along the inferior thyroid artery and drains to the upper tracheal lymph nodes.[5]

Nerves

The superior laryngeal nerve and recurrent laryngeal branches of the vagus nerve mainly innervate the larynx.

The superior laryngeal nerve arises from the inferior ganglia of the vagus nerve and descends adjacent to the pharynx, behind the internal carotid artery prior to splitting into the internal and external branches.

The branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (aka the external laryngeal nerve) descends beneath the sternothyroid muscle to supply the cricothyroid muscle. This is the only muscle of the larynx that is not supplied by the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

The internal branches of the superior laryngeal nerve (aka the internal laryngeal nerve) transverse with the superior laryngeal artery through the aperture in the thyrohyoid membrane. It provides sensory innervation to the laryngeal cavity superior to the level of vocal folds. It is responsible for the sensory afferent part of the cough reflex.

The recurrent laryngeal branches of the vagus nerve supply sensation to the laryngeal cavity below the level of the vocal folds. They run immediately posterior to the thyroid gland and are responsible for innervation of all the muscles of the larynx except the cricothyroid, and for sensation inferior to the vocal folds.[6]

Muscles

Intrinsic Muscles of the Larynx that Act on the Vocal Cords

- Tensors: Cricothyroid, vocalis

- Abductor: Posterior cricoarytenoid muscles

- Adductors: Lateral cricoarytenoid, transverse arytenoid

Intrinsic Muscles of the Larynx that Act on the Laryngeal Inlet

- Openers: Thyroepiglottic

- Closers: Aryepiglottic, oblique arytenoid

Extrinsic Muscles of the Larynx

- Elevators: Stylopharyngeus, salpingopharyngeus, palatopharyngeus, thyrohyoid

- Depressors: Sternohyoid, sternothyroid, omohyoid [7]

Physiologic Variants

Laryngoceles are anomalous air sacs within the supraglottic larynx and are classified as internal or external based on their relationship to the thyrohyoid membrane. Internal laryngoceles are comprised of a collection of air or serous fluid in the anterior portion of the laryngeal ventricle within the confines of the thyroid cartilage, versus external laryngoceles whose sacs protrude through the thyrohyoid membrane. Internal laryngoceles will typically present as cough, hoarseness, odynophagia, or airway obstruction. External laryngoceles will cause an anterior neck mass resembling an abscess or cyst.[8]

Surgical Considerations

The thyrohyoid membrane has been suggested as a target for an ultrasound-guided block of the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. Ultrasound-guided in-plane injections have been shown using the thyrohyoid membrane as a target plane for local anesthetic injection. This can provide anesthesia to the base of the tongue, posterior surface of the epiglottis, arytenoids, and aryepiglottic folds and can assist in airway management.[9]

Clinical Significance

Transection of the thyrohyoid membrane is rare but can be fatal. A prompt diagnosis and securing airway patency are essential in any patient with a neck injury.[3]

Lateral thyrohyoid ligament syndrome can cause acute or chronic cervical pain. Patients typically present with unilateral neck pain, odynophagia and foreign body sensation, and the pathognomonic feature of point tenderness with deep palpation along the axis of the lateral thyrohyoid ligament. Inflammation of the ligamentous, cartilaginous, or bursa-related anatomical structures might contribute and can be caused by overuse or factors such as a cough, voice abuse, or strenuous neck and upper limb movements. A majority of patients achieve improvement in symptoms with steroid and local anesthetic injection. There is no imaging to confirm this condition. Therefore it is critical for physicians to be aware of the diagnosis, as a physical exam demonstrating localized tenderness over the lateral thyrohyoid ligament axis is all that is required to make a diagnosis.[10]