Introduction

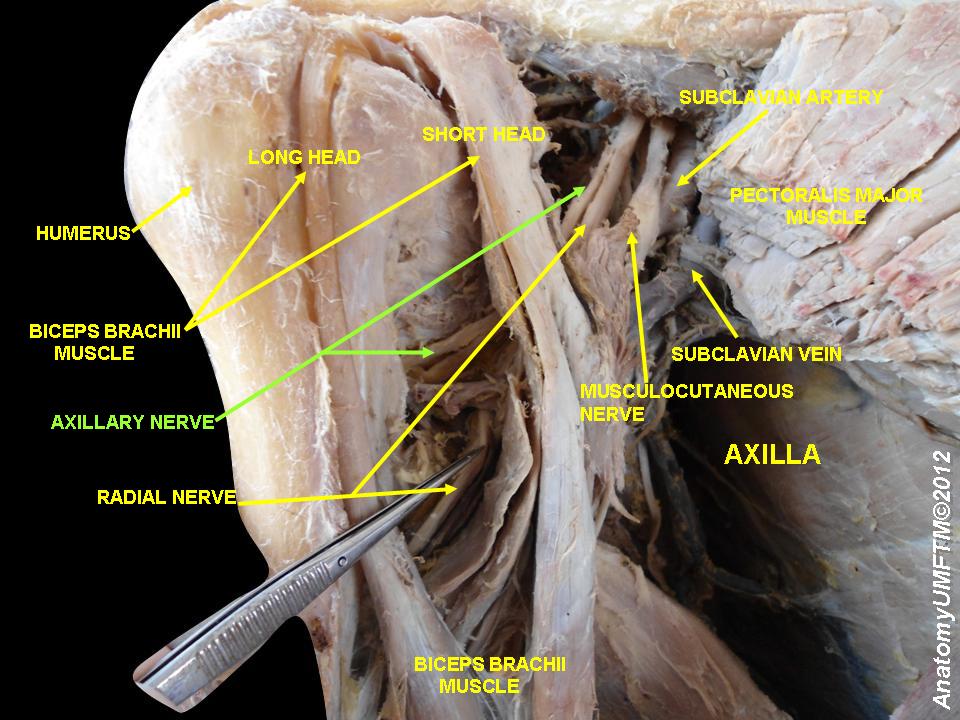

The brachial plexus is the network of innervation to the upper limb. It originates in the neck and passes between the anterior and middle scalene muscles. It courses beneath the transverse cervical artery in the posterior triangle of the neck and continues underneath the clavicle and first rib. Finally, it travels toward the axilla where the terminal branches arise to provide motor and sensory innervation to the upper limb. The brachial plexus is comprised of ventral rami of C5 down to T1, providing nervous stimulation for muscular actions including flexion, extension, pronation, supination, abduction, adduction, external and internal rotation at the shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand. It also provides sensory innervation to the upper limb. This nerve network begins as roots then continue to divide into trunks, divisions, cords, and lastly terminal branches. The 5 terminal branches are the musculoskeletal nerve, median nerve, ulnar nerve, radial nerve, and the axillary nerve. Each terminal branch has an area where it provides motor and sensory innervation in the upper limb. The regional orientation of each branch assists with understanding the actions which take place secondary to stimulation of specific muscles. When the body is in the anatomical position, the muscles of the arm and forearm which face anteriorly are mostly flexors, as opposed to muscles that are positioned posteriorly, which are primarily extensors. Muscles that cross joints and positions from anterior to posterior or posterior to anterior will participate in pronation or supination, respectively. The axillary nerve is the terminal branch and will be our area of focus to be discussed in this article.[1][2][3][4]

Structure and Function

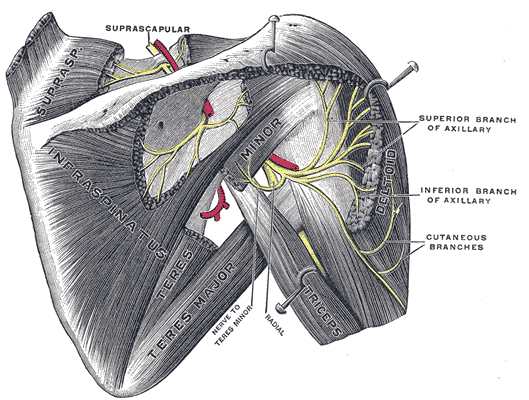

The axillary nerve begins at the ventral rami of C5 and C6 spinal nerves and continues as the smaller branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It innervates the deltoid and teres minor muscles via the anterior and posterior branches, respectively. Innervation of the deltoid muscles allows for the abduction of the arm after action from the supraspinatus has already reached 15 degrees. Teres minor is responsible for lateral rotation and also participates in maintaining the stability of the glenohumeral joint. The posterior branch of the axillary nerve also gives rise to the upper lateral cutaneous nerve after innervating teres minor. The upper lateral cutaneous nerve provides sensation to the inferior lateral deltoid region, at an area called the regimental badge area.[5][6][7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arising from the neck, posterior to the axillary artery and anterior to the subscapularis muscle, the axillary nerve travels toward the lower border of the subscapularis where it exits the axilla through the quadrangular space, alongside the posterior humeral circumflex artery and vein. The quadrangular space is bordered superiorly by the lower border of teres minor muscle, laterally by the surgical neck of the humerus, inferiorly by the upper boundary of teres major, and medially by the long head of the triceps brachial. After exiting the quadrangular space posteriorly, the anterior branch of the axillary nerve wraps around the surgical neck of the humerus, with the posterior humeral circumflex artery, to then innervate the deltoid muscle. The posterior branch continues from the quadrangular space to innervate the posterior portion of the deltoid, teres minor, and the skin of the lateral upper to mid arm.

Muscles

The deltoid muscle is primarily responsible for the abduction of the arm. It contributes to lateral rotation and extension of the posterior fibers, as well as medial rotation and flexion of the anterior fibers. It originates from the lateral third of the clavicle, the acromion, and the spine of the scapula, and inserts at the deltoid tuberosity of the lateral humerus. Teres minor is one of the muscles which stabilize the glenohumeral joint. It acts by laterally rotating the arm and helps to keep the head of the humerus in the shoulder capsule.

Clinical Significance

Injury to the axillary nerve usually presents as the result of an overstretched angle between the neck and the shoulder secondary to trauma or excessive force. Typical scenarios include a patient being thrown from a vehicle or falling from a height and landing rostrally in a position which stretches the angle between the neck and ipsilateral shoulder. For example, in the event where a fall results in the distance from the left ear to left shoulder is significantly decreased, the opposite side, where the right ear is pulled away from the right shoulder, is where the injury would occur. Nerve roots C5 and C6, which also make up the superior trunk of the brachial plexus, can become overstretched during birth as well. In the case of newborn delivery, failure of the Moro reflex can manifest as a sign of axillary nerve injury. The Moro reflex is an abduction then adduction, startle reflex which is expected from a baby roughly by 2 months of age. Both adduction and abduction components will not function correctly in this case. Stretching of the axillary nerve at spinal roots C5 and C6 interrupt the innervation to the deltoid and teres minor. The prolonged injury will lead to atrophy of the deltoid muscle, resulting in flattening of the shoulder curvature. Also, the arm will tract medially, given that teres minor no longer counters with lateral rotation. The limb also hangs to the side in an adducted position due to the failure of the deltoid muscle to counter the actions of the adductor muscles in the arm and chest. Avulsion or rupture of the superior trunk affects not only the axillary nerve but also the biceps brachial and brachialis, which accentuates the clinical manifestations of axillary nerve injury, as well as leads to a persistent extension at the elbow. This condition is known as Erb-Duchenne Palsy, also called Waiter's Tip syndrome. In addition to the previously stated, axillary nerve injury can result from an inferior dislocation of the humerus, as well as a fracture at the surgical neck of the humerus, where the anterior branch of the axillary nerve wraps around, exposing the nerve to potential harm. Dislocation of the humerus usually occurs in the inferior direction due to decreased ligament stability to hold the joint together inferiorly. Any irritation of the axillary nerve can also result in paresthesia, numbness, tingling, or overall loss in sensation at the regimental badge area because the cutaneous branch coming from the posterior axillary nerve is the only source of cutaneous innervation at this area. An abrupt onset of pain, following by an extended period of progressive muscle weakness, atrophy, and sensory deficit, is another condition that can affect the axillary nerve. This particularly rare condition, named Parsonage-Turner syndrome (PTS), has an insidious onset but can be precipitated by viral illness, trauma, history of autoimmune disease, or even surgery. It manifests in at least one nerve of the brachial plexus. Given that the axillary nerve is a terminal branch of the brachial plexus, it has the potential to be affected, leading to weakening of the muscles innervated by this nerve. PTS can also be called brachial neuritis or neuralgic amyotrophy.[8][9]