Continuing Education Activity

Seborrheic keratoses are epidermal skin tumors that commonly present in adult and elderly patients. They are benign skin lesions and often do not require treatment. However, it is essential to be able to differentiate these lesions from other benign and malignant skin tumors. This activity outlines the general evaluation and workup of Seborrheic keratoses in the outpatient setting and discusses common features of seborrheic keratosis as well as various treatment modalities that are available for the interprofessional team.

Objectives:

- Explain the common history and physical exam findings of seborrheic keratosis.

- Summarize the general workup, differential diagnosis, and confirming the diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.

- Review the various treatment modalities for seborrheic keratosis in the outpatient setting.

- Identify the importance of improving care coordination between health professionals to improve the outcomes of patients with seborrheic keratosis.

Introduction

Seborrheic keratosis is a common type of epidermal tumor that is prevalent throughout middle-aged and elderly individuals.[1] These lesions are one of the most common types of skin tumors seen by primary care physicians and dermatologists in the outpatient setting. Although seborrheic keratoses are benign tumors that often present with distinguishing features, there can be some morphological overlap with other malignant skin lesions. It is essential to recognize these features to differentiate these lesions from other benign and malignant skin tumors. Due to the benign nature of seborrheic keratosis, treatment is often not required. However, a majority of patients still opt to undergo some degree of treatment. Given the prevalence of these tumors, it is important to understand the workup and various treatment modalities for the management of seborrheic keratosis.

Etiology

Seborrheic keratosis is caused by the benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes, resulting in well-demarcated, round or oval, flat-shaped macules. They are typically slow-growing, can increase in thickness over time, and they rarely resolve spontaneously.

Epidemiology

Seborrheic keratosis is the commonest benign skin tumor, affecting over 80 million Americans.[2] Seborrheic keratosis is typically seen in patients greater than 50 years of age and become more frequent as one ages. Although seborrheic keratosis lesions are more common in the middle-aged and elderly, they can also present in young adults. There is no prevalence difference between males and females. However, seborrheic keratosis appears to be more frequent in populations with lighter skin tones.

Pathophysiology

Seborrheic keratosis results from benign clonal expansion of epidermal keratinocytes. There is believed to be a genetic component for the development of a high number of seborrheic keratosis lesions. However, the exact familial inheritance is not known. The exact pathogenesis of this skin condition is also not known at this time, but there is a possible correlation with fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) and or PIK3CA oncogenes.[3] Activating mutations in the tyrosine kinase receptor known as fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR3) are common in cases of sporadic seborrheic keratosis and are believed to be what drives the growth of this benign tumor. There are various subtypes of seborrheic keratosis, including acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, adenoid, irritated, and melanoacanthoma. These lesions can be complex and can have components of multiple subtypes on their pathology.

Histopathology

Under the microscope, seborrheic keratosis would typically show a proliferation of keratinocytes with keratin-filled cysts.[4] There can be lymphocytic infiltration present in inflamed or irritated lesions. Depending on the subtype, there can be varying degrees of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, pseudocysts, hyperpigmentation, inflammation, and dyskeratosis, although one sub-type is typically dominant in each lesion. Due to the high prevalence of this skin condition, it is crucial to biopsy those patients with atypical features and a higher clinical index of suspicion for malignancy.

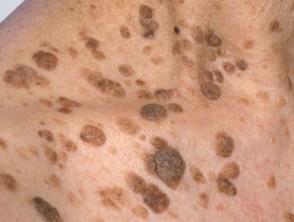

History and Physical

A thorough history and complete physical exam are necessary when evaluating a patient with numerous seborrheic keratosis. Clinically, seborrheic keratoses have a dull, waxy, verrucous surface resulting in their characteristic “stuck on” appearance. The color of these lesions can vary from light to dark brown, yellow, and grey, and they can present as an isolated lesion to tens or even hundreds of lesions. These tumors can generally occur anywhere on the body, except for the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. Depending on the lesion location, there can be chronic inflammation, which leads to pain, pruritus, erythema, and bleeding around the site. Generally, seborrheic keratosis is benign and slow-growing lesions, however, there should be a concern if there is sudden growth or emergence of multiple seborrheic keratoses. The sign of Leser-Trelat refers to the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratosis that is suggestive of internal malignancy, commonly associated with gastrointestinal or pulmonary carcinomas.[5]

Evaluation

The basis for diagnosis and workup of seborrheic keratosis are generally on their overall appearance. If the tumors are dark, uniform, slow-growing, and have the typical “stuck on” verrucous appearance, there is a high probability that they are benign, and further workup is not necessary. Examination with a dermatoscope would further help differentiate benign features from dysplastic or malignant tumors. Dermatoscope findings for seborrheic keratosis generally show milia cysts, comedo-like openings, fissures, and ridges. Overlapping lesions or high numbers of seborrheic keratosis can make the diagnosis and workup of these lesions more difficult. Patients with high numbers of seborrheic keratoses should receive careful screening, as there can be an increased chance of missing co-existing melanoma or pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Additionally, seborrheic keratosis is slow-growing and can become larger and thicker over time. There have been cases of a secondary tumor growing adjacent to or within a pre-existing seborrheic keratosis. A dermatologist referral should be a consideration in patients with a high number of lesions and high clinical suspicion of malignancy for a more thorough and team-oriented approach.

If there is uncertainty with the diagnosis or if there are other concerns for malignancy such as ulcerated lesions, rapid change in size, or overall very large lesions, a skin biopsy would be recommended to get a definitive answer.[6] Rapid growth and the emergence of multiple seborrheic keratoses can arise in several situations. Leser-Treélat sign involves the emergence of multiple seborrheic keratoses and is associated with underlying malignancy such as adenocarcinoma of the GI tract, leukemia, lymphoma, etc.[7] For these individuals, it is crucial to conduct a thorough history and physical, age-appropriate cancer screening, and order any additional labs based on risk factors and patient’s history. Other causes of a sudden eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses include chemotherapy as well as inflammatory dermatitis (eczema).

Treatment / Management

Various treatment modalities are available for the removal of seborrheic keratosis. Seborrheic keratosis is benign and typically does not warrant any treatment. However, a majority of patients still undergo some variation of therapy for these lesions. Usually, seborrheic keratoses removal is for cosmetic reasons or lesions that are consistently irritated and cause discomfort for the patient.[8] Suspicious, bleeding, rapidly growing or changing lesions carry a higher risk of malignancy, and should be biopsied and or removed. The choice of therapy should be individualized for the patient. Considerations should include the lesion size and thickness, the patient’s skin type, clinical suspicion for malignancy, and the physician’s clinical experience.

The most common and readily available treatment for seborrheic keratosis would be cryotherapy.[9] This method is efficacious and generally well tolerated by the patient. This method utilizes liquid nitrogen or CO2 to rapidly freeze/thaw the targeted cells, resulting in cell death. There are currently no set guidelines for freezing/thawing times, and they can vary depending on the thickness of the lesion. Thicker lesions may require multiple freeze/thaw cycles to effectively treat the area. Additionally, this treatment method does not permit any histologic confirmation of the lesion and should only be for low-risk, low clinical suspicion for malignancy. This method has a low post-procedure care regimen for the treated area; however, it can cause erythema, pain, and bulla formation. There have been some reported post-procedure hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation with the healing of these areas after therapy.

Another modality for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis would shave excisions. Typically, this treatment modality is for skin conditions primarily contained in the epidermis without the involvement of the dermis. These procedures require some type of local anesthesia, usually 1% lidocaine with or without epinephrine depending on the location of the lesion. A superficial excision is performed with a scalpel, special exfoliating blade, or double-edged razor blade to remove a thin slice of tissue containing the lesion. The specimen can then go to the lab for the exact pathology of the affected area. Another removal method for removal of seborrheic keratosis is electrodesiccation with or without curettage. This process is another method for removing superficial, epidermal lesions w/o invasion into the dermis. This technique usually requires the use of local anesthetic and can be performed in the office setting. This method uses the curette to scrape and remove the epidermal tissue followed by electrodesiccation with a hyfrecator or cautery unit; this is typically performed multiple times to ensure that there is adequate removal of the affected tissue. C&D (curettage and desiccation) provides efficient results and generally has a low rate of complications. Possible complications of C&D include infection, scarring, and hyperpigmentation.

Researchers are studying various types of topical agents are currently for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. Topical gels and creams used for hyperkeratotic skin conditions (such as tazarotene, imiquimod cream, alpha-hydroxy acids, and urea ointment) as well as vitamin D analogs (tacalcitol, calcipotriol) have been used for treating these lesions. Although there have been some promising results with the reduction or resolution of the seborrheic keratosis lesions, the studies were small, and further research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of these topical medications. Other topical agents for the treatment of SK include a diclofenac gel and potassium dobesilate. Diclofenac is a topical NSAID, and potassium dobesilate is an inhibitor of the FGF signaling pathway, but these were also small studies, and their efficacy is not well established. The FDA recently approved a topical hydrogen peroxide solution for the treatment for seborrheic keratosis. In 2018, there was a randomized, double-blinded placebo control trial conducted using a topical 40% hydrogen peroxide solution.[10][11] Overall, the application of topical hydrogen peroxide was well tolerated and was effective in the removal of seborrheic keratosis. The side effects of treatment were generally mild and included erythema, scaling, and hyperpigmentation.

Finally, laser therapy is another non-surgical option for patients in the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. There are two types of lasers utilized for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis, including ablative and non- ablative laser therapy. Ablative laser therapy includes (YAG and CO2 lasers), and non-ablative lasers (755 nm alexandrite laser) have been utilized for this purpose. Overall there have been multiple small studies, which have some efficacy in the treatment of seborrheic keratosis, however, further studies are needed.

Differential Diagnosis

The overall differential diagnosis for seborrheic keratosis is broad and should include malignant melanoma, actinic keratosis, lentigo maligna, melanocytic nevus, squamous cell carcinoma, and pigmented basal cell carcinoma.[12] Overlapping lesions or high numbers of seborrheic keratosis can make the diagnosis and workup of these lesions more difficult. Again, patients with large numbers of seborrheic keratosis require careful screening, as there can be an increased chance of missing co-existing malignant lesions.

Differential Diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis:

- Malignant melanoma

- Actinic keratosis

- Lentigo maligna

- Melanocytic nevus

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Pigmented basal cell carcinoma

Prognosis

Seborrheic keratoses are benign lesions and have a good overall prognosis. The primary reason for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis is cosmetic. There are multiple treatment modalities, which have good outcomes with minimal side effects or complications. Patients with numerous seborrheic keratosis should be evaluated more carefully as the high number of lesions can mask concomitant malignant lesions. The sign of Leser-Trelat is suggestive of an internal malignancy and would be associated with a worse prognosis.

Complications

Seborrheic keratoses are the most common type of benign skin lesions. They grow slowly, and they can become thicker over time. Depending on the location of these lesions, they can become irritated and cause pain and discomfort for the patient. Additionally, large numbers of these lesions can make the detection of other malignant skin lesions more difficult.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is essential to know that seborrheic keratoses are benign skin lesions that are very common in the adult and elderly population. Typically, there is no indication for the treatment of SK if there is no suspicion for malignancy. Seborrheic keratosis removal is primarily for aesthetic reasons or secondary to chronic irritation. There are a number of treatment options available, including cryotherapy, excision, and topical hydrogen peroxide solution.

Pearls and Other Issues

The sign of Leser-Trelat refers to the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratosis that is suggestive of internal malignancy, such as gastrointestinal or pulmonary carcinomas.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Seborrheic keratoses are the most common type of skin tumor seen by primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and dermatologists in the outpatient setting. Generally, they are benign and present with distinguishing features. However, there can be some morphological similarities with other malignant skin lesions. Overlapping lesions or high numbers of seborrheic keratosis can make the diagnosis and workup of these lesions more difficult. Primary care clinicians, including the nurse practitioner, should consult with the dermatologist if the diagnosis remains in doubt.

Patients with large numbers of seborrheic keratosis need screening, as there can be an increased chance of missing co-existing malignant skin lesions. A team-oriented approach between nurses, primary care providers, and dermatologists would result in the best outcome for patients with seborrheic keratosis. Early incorporation of dermatologists in the patient’s care could aid in the screening and identification of any new or suspicious skin lesions. Additionally, they would be able to integrate the newest and current treatment modalities, such as laser therapy. Nursing will often have more contact with the patient and can provide counseling as well as monitor treatment effectiveness following the procedure, and report to the managing clinician regarding their observations or if the patient has complications from treatment. While benign, seborrheic keratosis still require strong interprofessional teamwork between the clinicians (including specialists) and nursing to achieve optimal outcomes. [Level V]

Outcomes

The outcomes for patients with seborrheic keratosis are excellent.