Introduction

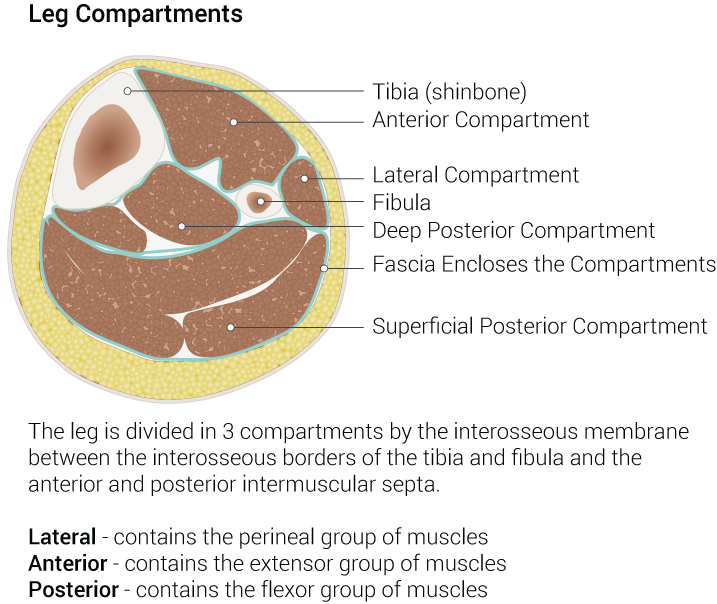

The lower leg subdivides into four compartments which are the anterior, lateral, superficial posterior and deep posterior compartments. The anterior compartment contains the tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, and fibularis tertius muscles, innervated by the deep peroneal nerve and supplied by the anterior tibial artery. The anterior compartment muscles function as the primary extensors of the ankle (dorsiflexion) and extensors of the toes.

The anterior compartment of the lower limb is susceptible to several pathologies including acute compartment syndrome resulting in foot drop, atherosclerotic plaque buildup of the arteries, and deep vein thrombosis. The anterior compartment is the most common site for acute compartment syndrome and is a medical emergency that requires fasciotomy of the involved compartment.[1]

Structure and Function

The key function of the muscles of the anterior compartment of the lower limb is dorsiflexion of the ankle and extension of the toes. Two of the muscles of the anterior compartment of the lower limb also invert the foot (tibialis anterior, flexor hallucis longus) and one weakly everts the foot (fibularis tertius).

Embryology

The limb buds of the embryo begin to form about 5 weeks after fertilization as the lateral plate mesoderm migrates into the limb bud region and condenses along the central axis to eventually form the vasculature and skeletal components of the lower limb.[2][3][4] Several factors influence the formation of the limb bud vasculature and musculature including retinoic acid, sonic hedgehog (SHH), HOX genes, apical ectodermal ridge (AER) and the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA). Retinoic acid is a global organizing gradient that initiates the production of transcription factors that specify regional differentiation and limb polarization. The apical ectodermal ridge (AER) produces a fibroblast growth factor (Fgf), which promotes the outgrowth of the limb buds by stimulating mitosis.[2][3][4] The specific fibroblast growth factor involved in hindlimb development is Fgf10, which is stimulated by Tbx4.[5] The zone of polarizing activity (ZPA) produces SHH, promoting the organization of the limb bud along the anterior-posterior axis. SHH activates specific HOX genes – Hoxd-9, Hoxd-10, Hoxd-11, Hoxd-12, Hoxd-13 – which are essential in limb polarization and regional specification.[2][3][4] These genes control patterning and consequently morphology of the developing limb in the human embryo.[5] Errors in Hox gene expression can lead to malformations in the limbs.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The anterior compartment of the lower limb receives its blood supply from the anterior tibial artery, a branch of the popliteal artery. The blood supply of the lower limb originates at the popliteal artery before splitting into the anterior tibial artery and posterior tibial artery. The posterior tibial continues down the posterior aspect of the leg to supply the posterior compartment muscles as well as giving off the peroneal artery, while the anterior tibial artery courses anteriorly between the tibia and fibula, passing through the interosseous membrane to supply the anterior muscles of the lower limb. It courses inferiorly down the leg and into the foot where it eventually becomes the dorsalis pedis artery, which supplies the tarsal bones and the dorsal aspect of the metatarsals. The dorsalis pedis artery eventually anastomoses with the lateral plantar artery to form the deep plantar arch.

Nerves

The deep peroneal nerve provides nerve supply to the anterior compartment of the leg. It is a branch of the common peroneal nerve, which is a branch of the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve branches at the apex of the popliteal fossa into the tibial and common peroneal nerves. The tibial nerve continues its course down the leg, posterior to the tibia supplying the deep muscles of the posterior leg. It terminates by dividing into the medial and lateral plantar nerves of the foot. The common peroneal nerve wraps around the neck of the fibula then divides and terminates into the superficial and deep peroneal nerves. The superficial peroneal will supply the lateral compartment of the leg, and the sensory to the dorsum of the foot. The deep peroneal will supply the motor innervation to the anterior compartment of the leg and sensation to the first dorsal toe webspace.

Surgical Considerations

The anterior compartment of the lower leg is the most common site for acute compartment syndrome.[1] When the pressure inside the anterior compartment increases, tissue perfusion can be compromised, which may lead to irreversible muscle and nerve damage – muscle necrosis. The most common causes of anterior compartment syndrome are trauma (fractures, crush injuries, contusions, gunshot wounds), tight casts or dressings, extravasation of IV infusion, burns, post-ischemic swelling, bleeding disorders, and arterial injury.[6] Fractures are the most common cause of anterior compartment syndrome, accounting for over 65% of the cases.[1]

Recognition of compartment syndrome is essential for the treatment and prevention of ischemia and necrosis of the neurovascular structures and muscle. The physical exam findings in compartment syndrome are often referred to as the “5 P’s”: pain with passive stretch of the toes/ankle, paresthesias, paralysis, palpable swelling, and pulselessness.[1] Pain with passive stretch is widely considered the most sensitive exam finding, while paralysis and pulselessness are late findings that are often irreversible. While largely a clinical diagnosis, the definitive diagnosis can be made with measurement of compartmental pressures. A resting compartment pressure of greater than 30 mm Hg or a “Delta P less than 300 mm Hg” (Delta P = diastolic blood pressure – compartment pressure) confirms the diagnosis of compartment syndrome.[1] In acute compartment syndrome, time is of the essence—if treated within 6 hours of ischemia, complete recovery is anticipated, whereas, after 6 hours of ischemia, necrosis occurs.[7] Definitive management of acute anterior compartment syndrome is with fasciotomy. Treatment of chronic anterior compartment syndrome can be more conservative involving activity modification, NSAIDs, stretching, orthotics, and physical therapy. Tendon transfers are a therapeutic consideration for patients with resultant foot-drop following missed compartment syndrome.

Another surgical intervention involving the anterior compartment of the leg involves bypass surgery for peripheral arterial disease. The arteries of the lower limb are particularly susceptible to atherosclerotic plaque buildup and peripheral arterial disease where the arterial lumen of the lower extremities becomes progressively occluded by atherosclerotic plaque, which can lead to decreased arterial blood flow.[2][8][9] Initial PAD management is with lifestyle changes and medications; however, if this fails, surgical intervention may be required.[2][8][9] Typical procedures for PAD include angioplasty, clot removal, and bypass surgery.

Clinical Significance

The anterior compartment of the leg is vital in the dorsiflexion of the foot, the extension of the toes, and inversion/eversion of the foot. For this reason, it is tested during the physical exam to assess the range of motion and motor strength of the ankles and toes. Weakened or absent motor strength can indicate muscle or nerve damage to the anterior compartment of the leg.

As discussed above, the anterior compartment of the leg is the most common site for compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome may occur acutely following blunt force injury or trauma, or as a chronic, an exertional syndrome commonly seen in athletes.[2][10] The muscle groups of the lower limb divide into compartments formed by strong, inflexible fascial membranes. Compartment syndrome occurs when increased pressure within one of these compartments’ compromises circulation and function to the tissues within that space (Lezak 2019; Mabvurre 2012). The anterior compartment contains muscles that primarily dorsiflex the foot at the ankle, extend the toes and invert/evert the foot. These muscles are innervated and supplied by the deep peroneal nerve and anterior tibial artery, respectively. Increased pressure in the anterior compartment can cause paresthesias, weakness of muscle action, and pain with passive stretch of the muscles.[2][10] Compartment syndrome constitutes a medical emergency that requires fasciotomy of the involved compartment.[2]

The anterior compartment of the leg can also be involved in deep vein thrombosis. DVT is one of the most frequent complications after major orthopedic surgery.[11] Most cases of DVT in the lower limb involve the muscular veins, posterior tibial vein, and peroneal vein, while the least common site is the anterior tibial vein.[11] Thrombosis of the anterior tibial vein is an extremely rare type of lower extremity thrombosis, with isolated anterior tibial thrombosis being even rarer, with a reported incidence of only 0 to 0.3% (Yao 2016). Treatment of DVT includes anticoagulation therapy, clot busters, vena cava filters, and compression socks.[11]