Continuing Education Activity

Brain herniation, also called brain code, requires early diagnosis and prompt management in order to prevent irreversible pathological cascades that eventually lead to respiratory arrest and subsequent death. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of brain herniation and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Outline the typical clinical presentation of a patient with brain herniation syndrome.

- Describe the rostral-caudal pattern of progression of each subtype of brain herniation and their typical associated imaging findings.

- Review treatment and management options available for patients with brain herniation.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination amongst the interprofessional team to upgrade the "target guided" multimodal management approach for patients with brain herniation syndrome.

Introduction

Brain herniation can be labeled as “brain code” to connate the emergent need to timely counteract such disastrous brain processes.[1]

The brain is encased within the skull, any rise in intracranial pressure is limited to some extent by the compensatory displacement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and changes in cerebral blood volume as evident by the Monro-Kellie doctrine.[2]

When it overrides these compensatory mechanisms, certain parts of the brain start herniating through specific foramina formed by the falx and the tentorial incisura within the skull, thereby propagating progressive herniation syndromes.

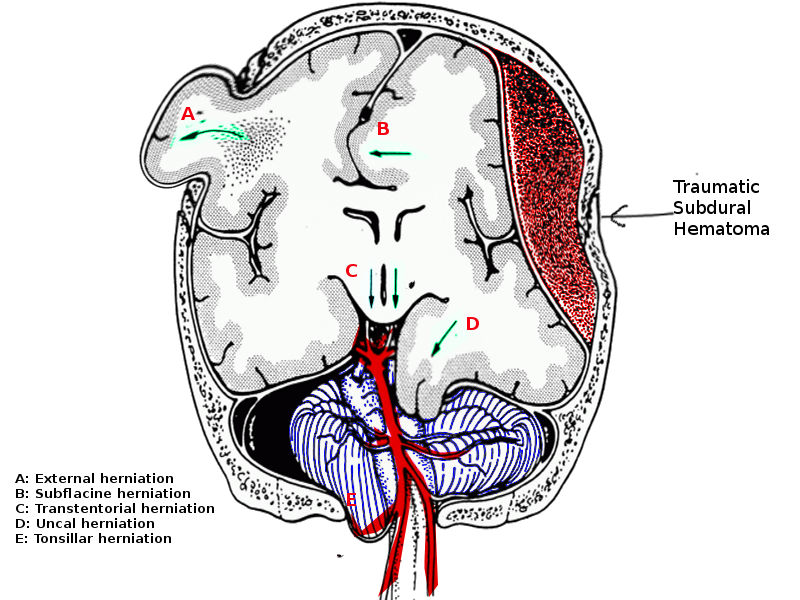

Brain herniation is a life-threatening event and needs urgent attention. The five types of brain herniations include:

- Subfalcine involves the cingulate gyrus, which is pushed against the falx cerebri.

- Transtenorial (uncal) involves the medial temporal lobe, which is often squeezed by a mass under and across the tentorium.

- Central involves herniation of both temporal lobes through the tentorial notch.

- A tonsillar herniation is caused by an infratentorial mass, forcing the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum.

- Upward herniation occurs when an infratentorial mass compressed the brainstem.

Etiology

There are multispectral factors that can predispose to raised intracranial pressure and brain herniation syndrome such as[1]:

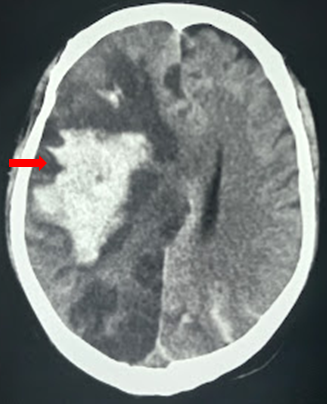

- Hematoma (traumatic epidural and subdural hematoma, contusions, intracerebral hemorrhage)

- Malignant infarction

- Tumors

- Infections (abscess, empyema, hydatid cyst)

- Hydrocephalus

- Diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Pneumocephalus (traumatic or postoperative)

- CSF over drainage

- Metabolic-hepatic encephalopathy

Epidemiology

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the predominant cause of death after traumatic injury. Raised intracranial pressure (ICP), especially correlates with poor TBI outcomes.[3]

Pathophysiology

Plum and Posner described cephalic-caudal sequential progressions of the brain during herniation.[4]

Brain herniation is classified as follows:

- Subfalcine herniation

- Transalar (transsphenoidal) herniation

- Transtentorial uncal herniation

- Central (trans-tentorial) herniation (descending and ascending)

- Cerebellar tonsillar herniation

- Transcalvarial herniation

1. Subfalcine Herniation

In subfalcine herniation, the ipsilateral cingulate gyrus gets migrated beneath the anterior falx, resulting in infarction along with the distal territory of the anterior cerebral artery.

2. Transalar (transsphenoidal) Herniation

In the posterior (descending) variant of transalar herniation, there may be infarction within the middle cerebral artery territory resulting from its compression within the sphenoid ridge. In anterior (ascending) transalar herniation, compression of the supra-clinoid segment of the internal carotid artery against the anterior clinoid process leads to infarction within the territory of anterior and middle cerebral arteries.

3. Transtentorial Uncal Herniation

Transtentorial uncal herniation leads to compression of the third nerve against the tentorial edge, resulting in a constriction followed by dilatation of the ipsilateral pupil. There may be infarction within the temporal or occipital lobe owing to compression of the calcarine branch of the posterior cerebral artery as well. The lateral displacement of the brain may be the primer for compression of the aqueduct of Sylvius, thereby leading to obstructive hydrocephalus. As the midbrain is further displaced, sometimes the contralateral cerebral peduncle is forced against the tentorium edge, creating Kernohan’s notch and damaging contralateral corticospinal tract, thereby resulting in paresis or paralysis ipsilateral to the mass lesion.

4. Central Herniation (descending and ascending)

As the pathological descent of the brainstem through the incisura progresses, venous congestion along with stretching and tearing of small perforators create Duret hemorrhages. Clinically there is a progression from abnormal flexor posturing to abnormal extensor response through the involvement of rubrospinal and the vestibulospinal tracts. Soon following this stage comes either a vegetative state or impending death due to damage to respiratory and cardiac centers in medulla by the herniated cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. Patients may exhibit characteristic triple components of Cushing triad constituting of hypertension, bradycardia, and irregular respirations.

Ascending transtentorial herniation can compression posterior cerebral or superior cerebellar arteries against the tentorium.

5. Cerebellar Tonsillar Herniation

Increased pressure in the posterior fossa forces the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. These will compress the lower part of the brain stem and upper cervical cord, resulting in life-threatening consequences. It usually occurs along with ascending or descending transtentorial herniation. Acute herniation can compress the posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, vertebral arteries, and their branches or the origin of the anterior spinal artery, which can lead to ischemia of brainstem, tonsils, and lower cerebellum.

6. Transcalvarial Herniation

In cases of calvarial defects such as in decompressive hemicraniectomy, the edematous brain may mushroom out through the defect, the path of least resistance, owing to the axonal stretch; this can sometimes lead to compression of cortical vessels by the bony margins thereby predisposing to hemorrhagic infarction.

History and Physical

Stringent neurological evaluation is paramount in assessing patients with brain herniation. Early identification of pupillary asymmetry and rapid correction of the underlying pathology help limit secondary insults.[5]

There are salient neurological signs and symptoms, while the patient progresses through the herniation syndromes.

In the case of subfalcine herniation, there is lower limb weakness owing to infarction of the corresponding motor homunculus following compression of pericallosal and callosomarginal vessels.

There will be ipsilateral anisocoria with contralateral motor weakness following uncal herniation. However, occasionally Kernohan notch phenomenon can give rise to ipsilateral weakness as well.

With further progression of raised intracranial pressure, there will be the lateral shift of the diencephalon leading to altered sensorium from distortion of the reticular activating system as well as hydrocephalus from torsion and obliteration of CSF pathways.

The onset of downward transtentorial herniation is evident by the presence of decorticate and decerebrate posturing along with loss of brainstem reflexes. The respiratory patterns progress through Cheyne stoke pattern of breathing to stages of hyperventilation, ataxia, and finally apnoea, which eventually leads to fixed dilated pupils and respiratory arrest owing to compression of the medullary respiratory centers.

In upward transtentorial herniation, there is an onset of Parinaud syndrome along with features of diabetes insipidus resulting from damage to pituitary stalk.

Evaluation

The radiological imaging also reveals specific characteristic markers associated with each herniation subtypes.[6]

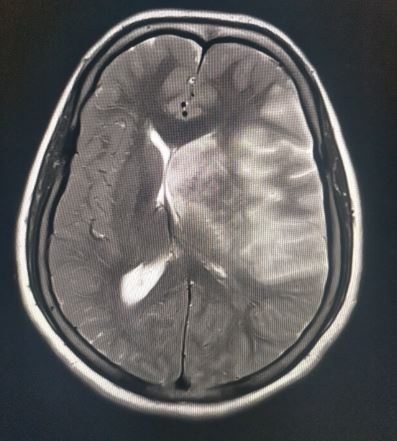

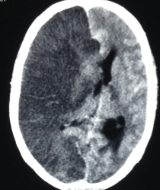

There is an effacement of the ipsilateral lateral horn with a displacement of septum pellucidum in subfalcine herniation, which is followed by progressive compression and obliteration of the basal cisterns along with hydrocephalus resulting from brain torsion. The uncal herniation causes widening of the ipsilateral cerebellopontine cisterns with the obliteration of the contralateral cerebellopontine cisterns.

The central herniation leads to complete obliteration of peri-mesencephalic and peri-medullary cisterns, truncated brainstem along with the presence of Duret hemorrhage. The upward herniation variant will lead to flattened quadrigeminal cisterns, 'spinning top' appearance of the midbrain, and associated hydrocephalus.

The imaging will also reveal characteristic infarction along with the vascular territory of compressed vessels. In terminal stages with global infarction, there will be a white cerebellar sign as well.

The cerebral auto-regulation becomes disrupted; thereby, the cerebral blood flow becomes pressure passive. The compliance of the brain diminishes with a fall in its compensatory reserve.

The ICP pressure waves show characteristic Lundberg A (plateau waves peaking to 50 mmHg and persisting for 5 to 20 minutes) and B waves (rhythmic oscillations occurring every 1 to 2 minutes peaking up to 20 to 30 mm Hg) with progressive ICP elevation.

ICP waveform shows a dicrotic wave (P2) higher than the percussion (P1) and the tidal wave (P3).

Treatment / Management

Brain trauma foundation guidelines recommend monitoring ICP in patients with severe TBI [Glasgow coma scale (GCS) of 3 to 8] and have either (1) abnormalities in CT of the head or (2) meet at least two of the following three criteria: age over 40 years; systolic blood pressure under 90 mmHg; or abnormal posturing.

The genesis for this approach is the changes in ICP being evident 6 hours before clinical signs and symptoms are observable in patients following herniation syndrome.[3] However, studies from ICP guided rescue therapy have produced mixed results.

There is still no level I evidence for any strategies targeted for managing refractory intracranial hypertension, with only level IIA evidence for the role of decompressive hemicraniectomy and level IIB evidence for the role of ICP monitoring. Thresholds for ICP and cerebral perfusion pressure guided therapies are 22 mm Hg and 60 to 70 mm Hg, respectively.

Proposed tiers in the management of refractory intracranial hypertension and resultant brain herniation.[1]

- Evacuation of mass lesions (hematoma, contusion, infarction, edema, tumors)

- Physiological neuroprotection

- Sedation, analgesics, and ventilation

- CSF drainage

- Osmotherapy

- Hyperventilation

- Hypothermia

- Barbiturate coma

- Decompressive hemicraniectomy

General Measures

- Most patients require mechanical ventilation and need to be paralyzed to avoid straining or agitation. Sedatives should be used to calm the patient.

- Hyperventilation is known to cause vasoconstriction and helps lower the intracranial pressure.

- Fluids should be restricted, but the patient must not be dehydrated.

- Diuretics like mannitol can be administered to lower the ICP.

- Blood pressure control is vital but needs to be adequate to perfuse the brain.

- In some patients with malignancies and abscesses, corticosteroids may reduce vasogenic edema.

- Hypothermia is widely used today as it slows down brain metabolism, but it also makes the patient prone to infections and arrhythmias.

- Pentobarbital coma can lower cerebral blood flow, but it can also cause hypotension.

Differential Diagnosis

Certain clinical entities can mimic brain herniation syndrome owing to rapid clinical and neurological deterioration in patients such as:

- Posttraumatic subclinical seizures

- Acute hydrocephalus

- Tension pneumocephalus

- Dyselectroytemia

- Meningitis

- CSF over-drainage syndrome

- Osteopetrosis

- Costello and posterior fossa crowding syndrome

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

A recent study found that decompressive hemicraniectomy in traumatic intracranial hypertension, even though having some minimal survival benefits, resulted in higher proportions of patients in vegetative states with higher disability compared to medical management.[7]

ICP guided therapy encompasses the need for stringent optimization of ICP between 10 to 17 mm Hg for a favorable outcome in these subsets of patients.[8]

However, to date, there is limited evidence to support the ICP guided therapy in improving the outcome in raised ICP.[3] Though labeled as being the central tenant in guiding the management algorithm, it has a propensity in driving interventions that may paradoxically harm the patients.

Prognosis

Different factors including duration of onset of herniation, age of the patient, presenting Glasgow coma scale, anisocoria, associated polytrauma, concurrent hypoxia, and hypotension, type of lesion (extradural hemorrhage vs. subdural hemorrhage), Marshall and Rotterdam CT scores, and ICP measurement all affect the prognosis. The further the herniation syndrome progresses, the chances of recovery of the patient becomes more dismal.

Complications

Brain herniation can progress from a subtle finding of pupillary asymmetry (uncal herniation) to an altered level of consciousness (compression of the reticular activating system), then progressing to the moribund stage of abnormal posturing (compression of the diencephalon and the brainstem), and finally death resulting from respiratory arrest (medullary compression).

There is associated infarction seen along with the vascular territory of the compressed vessels associated with each herniation subtypes. The final radiological outcome is global brain infarction, as evident with the presence of a white cerebellar sign in non-contrast CT brain imaging.[9]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The prime factor in the prevention of head injuries is public awareness in following traffic rules, wearing helmets, seat belts and avoiding drunk driving.[10]

Pearls and Other Issues

The central dogma in managing raised ICP is preventing secondary insults.[11]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Early management of primary injury and prevention of secondary insults such as hypoxia, hypotension, seizures, infection, etc. play a paramount role while managing these patients with herniation syndrome.[12]

There is no silver bullet in managing raised ICP and associated herniation syndrome. The outcome depends on multimodality monitoring in managing primary insult and minimizing secondary insults.[13]

All clinicians who manage patients with brain herniation should be familiar with its treatment and potential complications. Nurses play a vital role in the monitoring and should immediately consult with the physician if there are abnormal signs. Nurses also need to ensure that the patients have deep venous thrombosis and stress ulcer prophylaxis. Urinary output must be closely monitored to avoid over or under hydration. The blood pressure has to be adequate to perfuse the brain, and the ventilatory settings should be adjusted to provide hyperventilation. Pharmacists review the prescribed medications including barbiturates, mannitol, and antiseizure drugs, and check for drug interactions.

Targeted resuscitation, early specialist management, a timely intervention targeting primary insult, thereby minimizing secondary insults and target-driven care (ICP reduction below 20 mm Hg and CPP of around 60 mm Hg) are the cornerstones in efficiently managing patients with brain herniation.

Patient-centered 'care bundle' by an interprofessional team that includes physicians, specialty-trained nurses, and therapists, is vital during all stages of diagnosis and care, including the rehabilitative phase to achieve optimal patient outcomes. [Level 5]