Continuing Education Activity

This activity provides a detailed review of the complex congenital heart defect pulmonary atresia with the intact ventricular septum. This review article includes the epidemiology, embryological considerations, clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment of above mentioned complex heart defect and highlights the role of an interprofessional team in evaluating and treating the patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology and epidemiology of pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum.

Review appropriate history, physical, and evaluation of pulmonary atresia with the intact ventricular septum.

Outline the treatment and management options available for pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum.

Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the management of pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum and improve outcomes.

Introduction

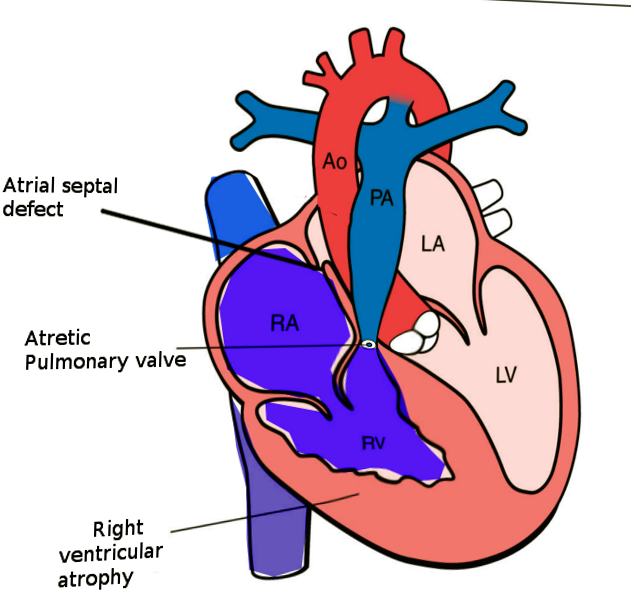

Pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum (PA-IVS) is one of the rare forms of congenital heart disease (CHD), accounting for less than 1% of total heart defects (see Image. Pulmonary Atresia With Intact Ventriciular Septum). This entity was first described by Hunter in 1783 and later by Peacock in 1869. As implied by the name, this disease is characterized by either membranous or long segment muscular atresia of the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) in the absence of communication at the level of ventricles. The spectrum of this disease range from simple membranous pulmonary atresia (PA) with normal-appearing right ventricle (RV) to hypoplastic RV with abnormal connections between the right ventricle and coronary arteries.

Etiology

An insult during the sensitive stages of the embryological development is thought to cause this heart defect. However, the precise abnormality that leads to PA-IVS remains unclear. Few theories postulated to explain the pathogenesis of this disorder include the primary insult to the pulmonary valve leading to an atretic valve, abnormal venous valve limiting the flow of the flow through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle, or as a result of abnormal coronary arterial development.

Epidemiology

PA-IVS is the third most common form of cyanotic CHD, with incidence varying anywhere between 4 to 8 per 100000 live births. In the United Kingdom and Eire collaborative study published in 1998, the incidence of this disorder was reported to be close to 4 per 100000 live births.[1] In another study published from the United States in 1984, the incidence of PA-IVS was close to 8 per 100000 live births.[2]

With the widespread availability and use of fetal echocardiography, the number of patients with complex forms of CHD, including PA-IVS, being diagnosed during pregnancy across the world is increasing. This fact has not only helped the physicians with planning the care of these neonates ahead of time but also increased the rates of elective termination of pregnancies following the diagnosis of complex CHD. This elective abortions of pregnancies with complex CHD has led to an overall reduction in the incidence of various forms of CHD. When including these elective terminations, the incidence of PA-IVS will be significantly higher than reported.

There is no predilection to either sex. Also, there has been no identified association with genetic disorders, even though De Stefano et al. in 2008 reported PA-IVS in monozygotic twins.[3] Genetic evaluation of twins in that report was notable for 55 kb deletion at WFDC8 and WFDC9, and the clinical significance of this gene deletion is unknown. Similarly, in 1992, Chitayat et al. from Canada, reported the incidence of PA-IVS in two siblings with no other associated cardiac anomalies.[4]

Developmental Considerations and Anatomical Characteristics:

With regards to the timing of occurrence, in 1983, Kusche and Van Mierop suggested that the insult that leads to PA-IVS happens later in gestation when compared to pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect (PA-VSD).[5] They suggested that the insult leading to PA-VSD occurs before the complete formation of the ventricular septum, whereas PA-IVS occur following the completion of ventricular septal formation.

Atresia of the pulmonary valve classifies into membranous and muscular forms. It is essential to distinguish between these two types, as a membranous form of PA has better long term prognosis when compared to muscular PA due to the higher incidence of abnormal connections (discussed in the latter part of this section) between the RV and coronary arteries. Due to high pressures in the RV, the tricuspid valve is generally abnormal. The tricuspid valve can be hypoplastic, dysplastic, and can have malformed chordal apparatus.

Another characteristic feature, if present, of PA-IVS, are the abnormal connections between the RV and coronary arteries. The RV, especially in patients with a competent tricuspid valve, is hypertensive due to lack of egress for the blood. Due to which the RV develop these abnormal connections with the epicardial coronary arteries, which help to decompress the ventricle. These abnormal connections, when present over time, leads to progressive stenosis of the coronary arteries related to high-velocity blood flowing through these abnormal connections. Due to progressive stenosis of the coronary arteries over time, some parts of the myocardium depends on right ventricle for the perfusion and is known as right ventricular dependent coronary circulation (RVDCC). Due to the progressive nature of RVDCC, it correlates with poor prognosis.

History and Physical

The most prevalent presenting signs and symptoms include cyanosis and desaturations. Neonates with PS-IVS become symptomatic following the closure of the patent ductus arteriosus as their pulmonary circulation is dependent on it. They rarely present or have the symptoms of decreased cardiac output due to obligatory right to left shunting at the level of atrial septum through foramen ovale. The presence of low cardiac output syndrome should raise suspicion for myocardial ischemia, especially in patients with coronary fistulae. As noted with many other forms of cyanotic CHD, these patients will not have an improvement in their cyanosis/desaturations with 100% oxygen delivery, failed hyperoxia test.

On cardiac auscultation, the examiner will note single first and second heart sounds. If there is a regurgitation of the tricuspid valve, a pansystolic murmur is audible at the left lower sternal border. An additional murmur related to the flow across patent ductus arteriosus might be audible in patients with patent ductus, especially following the initiation of prostaglandin infusion to maintain the ductal patency. The peripheral pulses and capillary refill time are usually normal except in patients with a severely restrictive right to left shunting at the level of atria.

Evaluation

2D echocardiography, an easy and readily available modality of cardiac evaluation, is used in the diagnosis of PA-IVS. Due to the widespread availability and use of fetal echocardiography in conjunction with prenatal screening for CHD, the majority of the patients with this disorder get diagnosed prenatally. In a recently published study on the utilization of fetal echocardiography, the overall rate of prenatal diagnosis for this specific heart defect was approximately 86%.[6]

The diagnosis of PA-IVS is possible with echocardiogram alone, but the additional information regarding the coronary circulation, which are significant predictors of outcomes and type of repair, cannot be discerned from this modality alone. In spite of providing information regarding the anomalous connections between the RV and coronary arteries, it is not useful in the diagnosis of RVDCC. Therefore, cardiac catheterization with angiograms is often needed to arrive at a complete diagnosis, which includes the assessment for fistulous connections between the RV and coronary arteries and RVDCC.

Echocardiogram:

The diagnosis of PA-IVS is possible from an apical four-chamber sweep. The absence of an outflow tract from the RV with intact ventricular septum is the diagnostic finding. While performing the echocardiography in these patients, special attention should focus on the anatomy of the interatrial septum, tricuspid valve, RV, and branch pulmonary arteries.

Interatrial septum:

These patients depend on the obligatory right to left shunting at the level of the interatrial septum to maintain the cardiac output and systemic perfusion. Therefore, it is prudent to evaluate for any obstruction across the interatrial septum. The subcostal views are generally optimal in imaging this part of the heart. A combination of 2D imaging, color doppler imaging, and spectral Doppler imaging are required to complete the assessment of the interatrial septum.

Tricuspid valve:

The assessment of the anatomy of the tricuspid valve is very crucial in these patients as the adequacy of the tricuspid valve is one of the major factor influencing the type of surgical repair. The assessment of the tricuspid valve should include the size of the tricuspid valve annulus, morphology of the valve leaflets, functional status of the valve (atretic vs. patent, competent vs. regurgitate). The patients with regurgitant tricuspid valves have a lower incidence of coronary anomalies as regurgitation through the valve helps to decompress the RV.

Right ventricle:

The morphological characteristics of the RV is another parameter that requires assessment in detail during the echocardiogram. Generally, the size of the RV is proportional to the size of the tricuspid valve. More than the absolute size of the right ventricle, it is important to evaluate the morphological characteristics of the right ventricle, which divides into three components, namely inflow, apical, and outflow. If the RV is tripartite, well-developed inflow, apical, and outflow components, the neonates can undergo biventricular repair even if it is hypoplastic, given that all the other characteristics favor the biventricular repair.

Cardiac catheterization:

The cardiac catheterization with angiocardiography is often used in the evaluation of patients with PA-IVS as it provides additional information regarding coronary circulation; this is particularly important in patients in whom decompression of the RV is a consideration. The primary goal of the cardiac catheterization is to assess for RVDCC. The diagnosis of RVDCC is made when a significant portion of the ventricular myocardium depends on RV for the blood supply. The angiographic criteria for the diagnosis of RVDCC include stenosis of two or more major coronary arteries or atresia of the coronary ostia and the myocardium distal to the obstruction receiving the blood supply via fistulous connections from the RV. Loomba et al. proposed the aortic perfusion score based on the angiographic characteristics of coronary perfusion, as a predictor of patient outcomes.[7]

Galindo et al. described various angiographic techniques that will help in obtaining adequate/optimal coronary imaging. The various techniques described in that article include RV angiogram, aortogram, aortogram with balloon occlusion of the aorta, and selective coronary angiograms. The evidence of myocardial ischemia on the surface electrocardiogram following the placement of the catheter in the RV (decompression of the RV from catheter-related tricuspid valve regurgitation) is very suspicious for RVDCC.

Treatment / Management

Medical Management:

Immediately following the diagnosis of PA-IVS, an attempt should be made to initiate prostaglandin infusion to maintain the patency of ductus arteriosus. This action is vital for the preoperative survival of these patients, as ductus arteriosus is the sole source of pulmonary blood flow. Also, it is crucial to manipulate pulmonary vascular and systemic vascular resistance to achieve optimal pulmonary and systemic blood flow.

Procedural management:

The patients with PA-IVS will need an intervention, either a catheter-based intervention or surgical procedure, as a neonate. As a result of the complexity and heterogeneity of this disorder, there is no single procedure that will be effective for all patients. Even though the biventricular repair is the ideal and preferred surgical approach, the management of this disorder has to be highly individualized. The preferred surgical or transcatheter intervention is influenced by several variables, which include tricuspid valve size and function, RV anatomy, coronary artery anatomy, and type of pulmonary atresia.

The currently available therapeutic algorithms are quite diverse. Chikkabyrappa et al. published an article in which they discuss the various therapeutic options for this disorder.[8] According to that article:

- Patients with adequate and tripartite RV size, which is functionally tripartite, tricuspid valve z-score greater than 2.5, and normal coronary artery anatomy would benefit from biventricular repair Radiofrequency perforation of the pulmonary valve for pulmonary atresia and surgical right ventricular outflow tract reconstruction for long segment atresia.

- Patients with borderline bipartite hypoplastic RV, tricuspid valve z-scores between -2.5 to -4.5 might benefit from attempted biventricular repair ± systemic to pulmonary shunt. These patients require close surveillance for RV growth, in the absence of which, they will benefit from one and a half ventricular repair.

- Single ventricular repair (bidirectional Glenn followed by Fontan) should be a consideration in patients with severe RV hypoplasia and patients with RVDCC.

- Primary heart transplantation might be a reasonable approach in patients with myocardial ischemia related to coronary artery abnormalities.

Clinicians should recall that the patients in categories 2, 3, and 4 will need systemic to pulmonary artery shunt or stenting of the PDA in the immediate newborn period.

Differential Diagnosis

Since the major presenting symptoms are desaturations and cyanosis, exclude other respiratory and cardiac causes of these symptoms.

Prognosis

Several studies have shown a gradual improvement in the survival of patients with this disorder, thought to be due to the advancements in the field of pediatric cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery. In a population-based study from the UK and Ireland published in 2005, the 1-year survival was about 71%, and 5-year survival was approximately 64%.[9] In the same article, the authors have found that low birth weight and unipartite right ventricle were the independent risk factors for death. RVDCC, especially atresia of the coronary ostia, is an independent risk factor for poor outcomes.[10]

Complications

In the absence of extensive aortopulmonary collaterals, PA-IVS is not compatible with life in the absence of ductal patency.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Pulmonary atresia with the intact ventricular septum (PA-IVS) is a rare and complex form of congenital heart defects with a broad spectrum of presentation. An insult during sensitive stages of embryological development is proposed to lead to PA-IVS. The presentation of this entity is similar to other complex cyanotic congenital heart defects with decreased pulmonary blood flow like tetralogy of Fallot.

The echocardiogram plays a vital role in diagnosing PA-IVS. Cardiac catheterization provides additional information regarding the status of the coronary circulation.

The management of patients with this heart defect is complex. Many therapeutic algorithms guide the medical team in the management of these patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach is needed to achieve optimal outcomes in these patients. The team most often include pediatric cardiologist, pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon, obstetrician, and maternal-fetal specialist (fetal diagnosis), neonatal-perinatal specialist, neonatal and ICU nurses, and a cardiac intensivist. In patients diagnosed prenatally, it is imperative to have a management plan even before the baby is delivered. In individual cases, it is not unreasonable to consider delivering the neonate in a tertiary care center, where pediatric cardiothoracic surgical services are available. Every attempt should be made to prevent delivery of the neonate during weekends and holidays when hospitals are not at full staffing.

Nursing will work with both the specialists and physicians as well as the family to help ensure care is optimal. They can offer to counsel and answer family questions. Surgical nurses are invaluable during any delivery and subsequent neonatal surgery and will participate in neonatal ICU care following procedures, reporting all status changes to the managing physicians. Only with this type of interprofessional collaboration can the mother and child achieve the best possible outcome. [Level 5]

The patents should receive detailed counsel from the team of nurses and doctors regarding heart defect and surgical strategies under consideration in the management of this complex disorder. Also, they understand the implications regarding the increased risk of heart defects with future pregnancies.