Continuing Education Activity

Bladder rupture is most commonly due to abdominal or pelvic trauma but may be spontaneous or iatrogenic in association with surgical or endoscopic procedures. Pelvic pain and gross hematuria are present in most patients. This activity explains the etiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of patients with bladder rupture and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care and rehabilitation of affected patients.

Objectives:

- Describe the etiology of bladder rupture.

- Summarize the evaluation of patients with bladder rupture.

- Outline the treatment options and rehabilitation of patients with bladder rupture.

- Identify interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and outcomes in patients with bladder rupture.

Introduction

Bladder rupture, a relatively rare condition, is most commonly due to abdominal or pelvic trauma but may be spontaneous or iatrogenic in association with surgical or endoscopic procedures. In adults, the bladder is well protected within the bony pelvis. As such, the vast majority of bladder injuries occur in association with pelvic fractures, particularly those involving the pubic rami. Pelvic pain and gross hematuria are present in most patients. Diagnosis is confirmed with retrograde cystography, either with computed tomography (CT) or plain films. Bladder rupture may occur in the peritoneal space but are more commonly extraperitoneal. Uncomplicated extraperitoneal ruptures are frequently managed non-operatively with a Foley catheter, while intraperitoneal ruptures require surgical repair.[1][2][3][4][5]

Etiology

Blunt force trauma in association with motor vehicle crashes accounts for most cases of bladder rupture. Motorcycle crashes are also commonly associated with pelvic trauma and can be associated with bladder rupture as well. Intraperitoneal ruptures usually occur when the full bladder is subjected to compressive forces on the lower abdomen. Extraperitoneal ruptures are usually associated with pelvic fractures either due to compressive forces on the pelvis causing rupture of the anterior or lateral bladder wall or from direct penetration of the bladder by bony fracture fragments. Falls and penetrating missiles are less common causes.[6][7][8]

Iatrogenic injury to the bladder may be associated with gynecological and colorectal surgery, urologic procedures, and Foley catheter placement. Bladder punctures most commonly occur in association with midline trocar placement below the umbilicus during laparoscopic procedures. Ensuring the bladder is empty, preferably with a catheter inserted prior to trocar placement, helps to minimize this risk.

Spontaneous bladder rupture is quite rare and is associated with high mortality. Cases have been reported in association with vaginal delivery, hemophilia, malignancy, radiation, infection, and urinary retention.

Epidemiology

Bladder injuries occur in about 1.6% of patients with blunt abdominal trauma. Approximately 60% of bladder injuries are extraperitoneal, 30% are intraperitoneal, and the remaining 10% are both extra and intraperitoneal. Overall, the incidence of intraperitoneal bladder rupture is much higher in children because of the intra-abdominal location of the bladder at a young age.

Pathophysiology

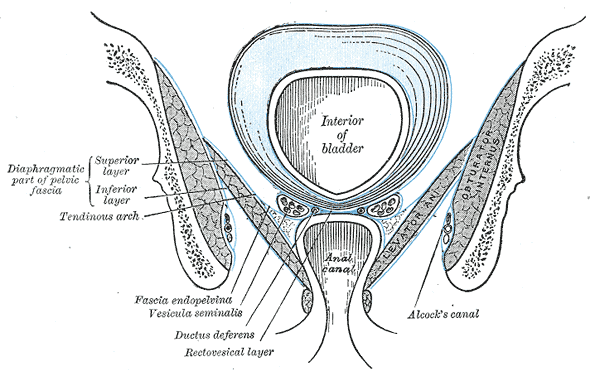

In adults, the empty bladder is well protected within the bony pelvis, but a full bladder may be distended to reach the level of the umbilicus, making it more vulnerable to injury. In very young children, the bladder is an intraabdominal organ, exposing it to injury in the setting of trauma. The weakest part of the bladder is the peritoneal dome. Spontaneous and iatrogenic ruptures are usually intraperitoneal, while traumatic ruptures, especially those associated with pelvic fracture, tend to be extraperitoneal.

Bladder rupture may be extraperitoneal or intraperitoneal. The type of bladder rupture depends on the location of the injury and its relationship with the peritoneal reflection as below:

- If the bladder rupture is above the peritoneal reflection (on the bladder dome), the urine extravasation will be intraperitoneal.

- If the bladder rupture is below the peritoneal reflection and not on the dome, the urine extravasation will be extraperitoneal.

Extraperitoneal Rupture

The majority of extraperitoneal rupture cases are associated with a pelvic fracture. This may be due to the deceleration injury and fluid inertia combined with the shearing frictional force that develops when the pelvic ring is fractured or deformed. Sometimes the extraperitoneal rupture may be due to perforation by bone fragments. With extraperitoneal rupture, the contrast will extravasate the bladder base and confined to the perivesical space.

Intraperitoneal Rupture

The bladder dome is well supported and is often the site of intraperitoneal rupture. The mode of injury is an increase in intravesical pressure and compression from the adjacent pelvis. Intraperitoneal bladder rupture can occur following steering wheel trauma and a direct blow. Urine will drain into the abdominal cavity, and the diagnosis is not always easy. As the urine gets resorbed into the systemic circulation, major electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities may become apparent. In addition, the patient may develop anuria. The diagnosis may be confirmed with urinary paracentesis or extravasation of urine on an imaging study.

History and Physical

In most cases, patients with bladder rupture have gross hematuria (77% to 100%). Other symptoms of bladder rupture include pelvic pain, lower abdominal pain, and difficulty voiding. It is important to note that trauma to the urinary tract is frequently associated with other traumatic injuries.

Pelvic fractures should raise the suspicion of injury to the bladder, urethra, rectum, and vagina. A careful physical exam is critical to the timely diagnosis of these injuries. Any pelvic fracture may be associated with bladder rupture, but fractures that involve the anterior arch or all four pubic rami significantly increase the risk. Pelvic fractures with ring disruption and those associated with posterior injury through the sacrum or ileum are also at high risk for bladder rupture.

Spontaneous ruptures present with pelvic pain, renal failure, urinary ascites, and sepsis.

More important, bladder rupture is often associated with colon injuries.

Evaluation

Urinalysis will show gross hematuria. Fewer than 1% of patients with bladder rupture present with urinalysis containing less than 25 red blood cells per high power field. Spontaneously voided specimens are preferable but often not practical in patients with severe injury. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine may be elevated due to peritoneal absorption of urine, especially if delayed presentation after injury.[9][10][11]

Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) exam may show free fluid in the pelvis in patients with intraperitoneal bladder rupture. The FAST exam does not distinguish urine from blood, making ultrasound less specific for intraperitoneal bleeding in patients with pelvic trauma.

Pelvic trauma and blood at the urethral meatus should raise the concern for urethral injury, and a retrograde urethrogram (RUG) should be performed before the blind placement of a urinary catheter.

Stable patients with gross hematuria and pelvic fractures require a retrograde cystogram to assess for bladder rupture. A retrograde cystogram is also recommended to assess patients with gross hematuria or symptoms suggesting bladder rupture even in the absence of pelvic fracture. However, the presence of pelvic fracture does not require a retrograde cystogram in all patients, especially those without hematuria or high-risk fracture patterns. Plain film and CT cystograms have similar sensitivity and specificity. Mechanism and associated injuries often determine the type of imaging a provider uses. Passive bladder filling by clamping the foley is inadequate, and bladder distention with retrograde filling is necessary to avoid missing more subtle injuries. Retrograde cystogram and urethrogram may interfere with the interpretation of pelvic angiography and should be deferred in unstable patients requiring embolization for control of pelvic hemorrhage. Traditionally, fluoroscopic cystography was used to assess the suspected cases of bladder rupture. However, this is a time-consuming investigation, and now, a CT-retrograde cystogram is considered to be the imaging study of choice as it also allows us to characterize other pelvic structures.[12]

Patients with penetrating pelvic trauma and gross or microscopic hematuria require an evaluation of the bladder. Depending on the clinical situation, this may be surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic.

Treatment / Management

American urological association (AUA) guidelines recommend that intraperitoneal bladder ruptures be surgically repaired. Most intraperitoneal ruptures associated with blunt trauma are large “blow out” injuries to the dome of the bladder. They will not heal spontaneously with urinary catheter drainage alone. Unrecognized and unrepaired intraperitoneal bladder ruptures may lead to peritonitis, sepsis, and renal failure. Since many are associated with major trauma, open repair is most common, but laparoscopic repair may be appropriate in some circumstances. During operative evaluation of bladder rupture at the dome, it is recommended to evaluate the entire bladder and not just repair the obvious injury. This may require enlarging an existing injury in order to evaluate the trigone area of the bladder. Repair of the bladder injury may be single or double-layered closure. It is recommended to avoid permanent suture on the mucosal repair as this may be a nidus for future stone formation. A Foley catheter is routinely left in the bladder after repair. Follow-up cystography should be performed to confirm healing in complex cases.[13]

AUA guidelines recommend that uncomplicated extraperitoneal bladder injuries be managed conservatively with catheter placement. Standard therapy involves leaving the catheter in place for two to three weeks, but it may be left in longer in some cases. Extraperitoneal ruptures that do not heal after four weeks of catheter drainage should be considered for surgical repair. Complicated extraperitoneal bladder ruptures, such as those associated with bone fragments within the bladder and those associated with vaginal or rectal injuries, often require operative repair. Bladder neck injuries often will not heal without surgical repair. Follow-up cystography should be used to confirm healing after treatment with a urinary catheter.

Catheter drainage can usually be performed with a urethral catheter. A suprapubic cystostomy is rarely required following surgical repair unless a urethral injury is also present, and a catheter is unable to be placed secondary to urethral disruption. Urinary catheters have shown to be adequate, resulting in a shorter length of stay and lower morbidity.

Differential Diagnosis

Bladder trauma can result from trauma or iatrogenically from a surgical procedure. Following differentials must be kept in mind while assessing a patient with bladder trauma:

- Child abuse

- Penile trauma

- Sexual assault

- Urethral trauma

- Vaginal trauma

Prognosis

Bladder perforation is no longer fatal as it once was. With more awareness and better imaging, most cases are diagnosed quickly. In some cases, surgery may help with the speed of healing and shorten the hospital stay. The overall prognosis depends on other injuries. When the injury of the bladder neck, urethra, and pelvic floor muscle, some patients may develop urinary incontinence.

Complications

Complications can occur due to bladder rupture itself because of extravasation of urine in the abdomen or due to its surgical management. Few complications are:

- Pelvic abscess

- Intraabdominal infection

- Hemorrhage

- Renal failure

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Urinary tract infection

- Urinary urgency

- Wound dehiscence

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most bladder injuries require a urinary catheter to drain the bladder for some time until the bladder injury is healed. Patients should be taught about catheter care and hygiene. Patients who have undergone surgery are instructed to return after 10 days for staple removal. Xray cystogram is repeated after 14 days of surgery to check healing and if any leakage exists. If the cystogram is normal then the catheter is removed. Some patients who have severe injuries can develop urinary incontinence, they should be counseled about that.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bladder rupture is not a common injury, but when it presents its diagnosis and management are best done with an interprofessional team that consists of a surgeon, urologist, nephrologist, trauma surgeon, emergency department provider, and specialty trained nurses.

There are guidelines released by the AUA for the repair of bladder rupture. These patients do need close follow-up after surgery to ensure that bladder function is intact.

Nurses looking after patients with bladder rupture should have a sign at the head of the bed that the Foley is not to be removed unless ordered by the surgeon. Nurses should also educate patients and their families that incontinence may develop for a short time after the catheter is removed. The nurses should assist in encouraging the patient to return if complications arise, such as difficulty voiding or fever. The nurse should arrange follow-up of complications with the interprofessional team.

In some patients, catheter drainage can usually be performed with a urethral catheter. A suprapubic cystostomy is rarely required following surgical repair unless a urethral injury is also present, and a catheter is unable to be placed secondary to urethral disruption. Urinary catheters have shown to be adequate, resulting in a shorter length of stay and lower morbidity. Open communication between the nurses and urologist is important to ensure good outcomes.

Overall, prompt repair of bladder injuries is associated with good outcomes.[14] [Level 5]