Continuing Education Activity

Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, is an autoimmune disease in which thyroid cells are destroyed via cell and antibody-mediated immune processes. It is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in developed countries. In contrast, the most common cause of hypothyroidism worldwide is an inadequate dietary intake of iodine. The pathophysiology of Hashimoto thyroiditis involves the formation of antithyroid antibodies that attack the thyroid tissue, causing progressive fibrosis. The diagnosis can be challenging, and consequently, the condition is sometimes not diagnosed until late in the disease process. The most common laboratory findings demonstrate elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and low thyroxine (T4) levels, coupled with increased antithyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of Hashimoto thyroiditis and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of Hashimoto thyroiditis.

- Describe the pathophysiology of Hashimoto thyroiditis.

- List the treatment and management options available for Hashimoto thyroiditis.

- Employ interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and care delivery to advance treatment for patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis.

Introduction

Hashimoto thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease that destroys thyroid cells by cell and antibody-mediated immune processes. It is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in developed countries. In contrast, worldwide, the most common cause of hypothyroidism is an inadequate dietary intake of iodine. This disease is also known as chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. The pathology of the disease involves the formation of antithyroid antibodies that attack the thyroid tissue, causing progressive fibrosis. The diagnosis is often challenging and may take time until later in the disease process. The most common laboratory findings demonstrate elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and low levels of free thyroxine (fT4), coupled with increased antithyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies. However, earlier on in the course of the disease, patients may exhibit signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings of hyperthyroidism or normal values. This is because the destruction of the thyroid gland cells may be intermittent.

Women are more often affected. The female-to-male ratio is at least 10:1. Although some sources cite diagnosis happening more so in the fifth decade of life, most women are diagnosed between the ages of 30 to 50 years. Conventional treatment is comprised of levothyroxine at the recommended dose of 1.6 to 1.8 mcg/kg/day. The T4 converts to T3, which is the active form of thyroid hormone in the human body. Excessive supplementation can lead to deleterious and morbid effects, such as arrhythmias (the most common being atrial fibrillation) and osteoporosis. In this chapter, we review the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Hashimoto thyroiditis.[1][2]

Etiology

The etiology of Hashimoto disease is very poorly understood. Most patients develop antibodies to a variety of thyroid antigens, the most common of which is anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO). Many also form antithyroglobulin (anti-Tg) and TSH receptor-blocking antibodies (TBII). These antibodies attack the thyroid tissue, eventually leading to inadequate production of thyroid hormone. There is a small subset of the population, no more than 10% to 15%, with clinically evident disease that are serum antibody-negative. Positive TPO antibodies presage the clinical syndrome.[3][4]

It can be part of the Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome type 2 with autoimmune adrenal deficiency and type-1 DM.[5] Hashimoto thyroiditis is also related to several other autoimmune diseases, such as pernicious anemia, adrenal insufficiency, and celiac disease.

Ruggeri et al. found that Hashimoto disease is associated with a variety of different nonthyroidal autoimmune diseases (NTADs), and diagnosis in adulthood made these even more prevalent.[6]

Epidemiology

After age six, Hashimoto is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in the United States and in those areas of the world where iodine intake is adequate. The incidence is estimated to be 0.8 per 1000 per year in men and 3.5 per 1000 per year in women. Twin studies have shown an increased concordance of autoimmune thyroiditis in monozygotic twins as compared with dizygotic twins. Danish studies have demonstrated concordance rates of 55% in monozygotic twins, compared with only 3% in dizygotic twins.[7] This data suggests that 79% of predisposition is due to genetic factors, allotting 21% for environmental and sex hormone influences. The prevalence of thyroid disease, in general, increases with age.

Pathophysiology

The development of Hashimoto disease is thought to be of autoimmune origin, with lymphocyte infiltration and fibrosis as typical features. The current diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms correlating with laboratory results of elevated TSH with normal to low thyroxine levels. It is interesting to note, however, that there is little evidence demonstrating the role of antithyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibody in the pathogenesis of autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD). Anti-TPO antibodies can fix complement and, in vitro, have been shown to bind and kill thyrocytes. However, to date, there has been no correlation noted in human studies between the severity of disease and the level of anti-TPO antibody concentration in serum. We do, however, know that positive serum anti-TPO antibody concentration is correlated with the active phase of the disease.[8] Other theories implicated immune complexes, containing thyroid directed antibodies, as culprits of thyroid destruction.

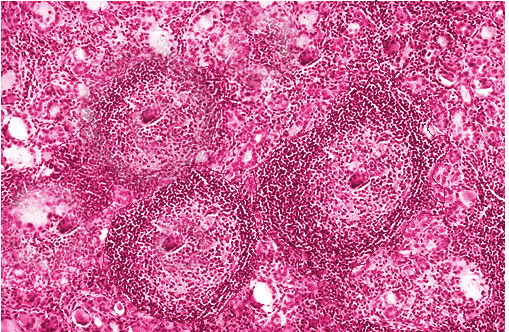

Histopathology

On pathologic examination, there is a diffuse, symmetric enlargement of the thyroid. The capsule is often intact with a prominent pyramidal lobe. When cut, the surface is similar to that of lymph nodes, with a pale brown to yellow color. Interlobular fibrosis may or may not be present. Atrophy may also occur, and in some patients, the gland may become nodular or asymmetric. However, necrosis or calcification does not occur and would suggest a different diagnosis.

History and Physical

The organ system manifestations of Hashimoto thyroiditis are varied due to the nature of the disease. Initially, patients may have bouts of hyperthyroid symptoms, as the initial destruction of thyroid cells may lead to the increased release of thyroid hormone into the bloodstream. Eventually, when enough destruction has been caused by the antibody response, patients exhibit symptoms of hypothyroidism. These symptoms are insidious and variable and may affect almost any organ system in the body.

The classic skin characteristic associated with hypothyroidism is myxedema, which refers to the edema-like skin condition caused by increased glycosaminoglycan deposition. This, however, is uncommon and only occurs in severe cases. Skin can be scaly and dry, especially on the extensor surfaces, palms, and soles. Histologic examination reveals epidermal thinning. Increased dermal mucopolysaccharides cause water retention and, in turn, pale-colored skin.

The rate of hair growth slows, and hair can be dry, coarse, dull, and brittle. Diffuse or partial alopecia is not uncommon.

Decreased thyroid function can increase peripheral vascular resistance by as much as 50% to 60% and reduce cardiac output by as much as 30% to 50%. Bradycardia may result from a loss of chronotropic action of thyroid hormone directly on the sinoatrial cells. However, most patients have a few symptoms directly attributable to the cardiovascular system.

Fatigue, exertional dyspnea, and exercise intolerance are likely associated with a combination of limited pulmonary and cardiac reserve in addition to decreased muscle strength or increased muscle fatigue. Hypothyroid rats have been shown to have decreased endurance. Biochemical changes in this population have shown decreased muscle oxidation of pyruvate and palmitate, increased utilization of glycogen stores, and diminished fatty acid mobilization. Muscle weakness and myopathy are important features.

The presentation may also be subclinical. Early symptoms may include constipation, fatigue, dry skin, and weight gain. More advanced symptoms may include cold intolerance, decreased sweating, nerve deafness, peripheral neuropathy, decreased energy, depression, dementia, memory loss, muscle cramps, joint pain, hair loss, apnea, menorrhagia, and pressure symptoms in the neck from goiter enlargement such as voice hoarseness.

Physical findings may include:

- Cold and dry skin

- Facial edema, particularly periorbital, as well as nonpitting edema involving the hands and feet

- Brittle nails

- Bradycardia

- The delayed relaxation phase of tendon reflexes

- Elevated blood pressure

- Slow speech

- Ataxia

- Macroglossia

Furthermore, patients can have an accumulation of fluid in the pleural and pericardial cavities rarely. Myxoedema coma is the most severe clinical presentation and has to be managed as an endocrine emergency within patient care.

Evaluation

Hashimoto thyroiditis is an autoimmune disorder of inadequate thyroid hormone production. The biochemical picture indicates raised thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in response to low free T4. A low total T4 or free T4 level in the presence of an elevated TSH level confirms the diagnosis of primary hypothyroidism.

Integrative and functional medicine practitioners may also assess free T3 and reverse T3 levels; however, Western medicine does not use this approach.

The presence of anti-thyroid peroxidase and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies suggests Hashimoto thyroiditis. However, 10% of patients may be antibody negative.

Anemia is present in 30 to 40%.

There can be decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), renal plasma flow, and renal free water clearance with resultant hyponatremia.

Creatine kinase is frequently elevated.

Prolactin levels may be elevated.

Elevated total cholesterol, LDL, and triglyceride levels can occur.

A thyroid ultrasound assesses thyroid size, echotexture, and whether thyroid nodules are present; however, it is usually not necessary for diagnosing the condition in the majority.[9][10]

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of treatment for hypothyroidism is thyroid hormone replacement. The drug of choice is titrated levothyroxine sodium administered orally. It has a half-life of 7 days and can be given daily. It should not be given with iron or calcium supplements, aluminum hydroxide, and proton pump inhibitors to avoid suboptimal absorption. It is best taken early in the morning on an empty stomach for optimum absorption.

The standard dose is 1.6 - 1.8 mcg/kg per day, but it can vary from one patient to another. Patients less than 50 years old should be commenced on a standard full dose; however, lower doses should be used in patients with cardiovascular diseases and the elderly. In patients older than 50 years, the recommended starting dose is 25 mcg/day, with reevaluation in six to eight weeks. In contrast, in pregnancy, the dose of thyroxine needs to be increased by 30%, and in patients with short-bowel syndrome, increased doses of levothyroxine are needed to maintain a euthyroid state.

There is less evidence to support an autoimmune/anti-inflammatory diet. The theory behind the inflammation has to do with leaky gut syndrome, where there is an insult to the gut mucosa, which allows the penetrance of proteins that do not typically enter the bloodstream via transporters in the gut mucosa. It is theorized that a response similar to molecular mimicry occurs, and antibodies are produced against the antigens. Unfortunately, the antigen may be very structurally similar to thyroid peroxidase, leading to antibody formation against this enzyme. The concept of an autoimmune diet is based on healing the gut and decreasing the severity of the autoimmune response. More research is required on this topic before it becomes a part of the guidelines.

Differential Diagnosis

- Euthyroid sick syndrome

- Goiter

- Graves disease (diffuse toxic goiter)

- Hypopituitarism (panhypopituitarism)

- Lithium-induced goiter

- Nontoxic goiter

- Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 1

- Polyglandular autoimmune syndrome type 2

- Thyroid cancer (lymphoma)

- Toxic nodular goiter

Pearls and Other Issues

Hashimoto thyroiditis (HT) is one of the most frequent autoimmune diseases and has been reported to be associated with gastric disorders in 10% to 40% of patients. About 40% of patients with autoimmune gastritis also present with Hashimoto thyroiditis, according to research by Cellini et al. Chronic autoimmune gastritis (CAG) is characterized by the partial or complete disappearance of parietal cells leading to impairment of hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor production. The patients go on to develop hypochlorhydria-dependent iron-deficient anemia, leading to pernicious anemia and severe gastric atrophy.

Thyrogastric syndrome was first described in the 1960s when thyroid autoantibodies were found in a subset of patients with pernicious anemia and atrophic gastritis. The latest guidelines have incorporated the two aforementioned autoimmune disorders into a syndrome now known as a polyglandular autoimmune syndrome (PAS). This is characterized by two or more endocrine and nonendocrine disorders. The thyroid gland develops from the primitive gut, and therefore the thyroid follicular cells share similar characteristics with parietal cells of the same endodermal origin. For example, both are polarized and have apical microvilli with enzymatic activity, and both can concentrate and transport iodine across the cell membrane via the sodium/iodide symporter. Iodine not only plays an essential role in the production of thyroid hormone, but it is also involved in the regulation of gastric mucosal cell proliferation and acts as an electron donor in the presence of gastric peroxidase, and assists in the removal of free oxygen radicals.

It is important to note that due to the pharmaceutical formation of thyroxine available worldwide, there can be problems with absorption in patients with disorders of the gastric mucosa. Most levothyroxine is obtained by salification with sodium hydroxide, making sodium levothyroxine. The absorption of T4 occurs in all areas of the small intestine and ranges from 62% to 84% of the ingested dose. Decreased gastric acid secretion can disrupt this percentage and may cause issues with decreased absorption of most pharmaceutical grade forms of levothyroxine, except for liquid-based or soft gel formations.

Clinically, it is important to note the association between thyroid and gastric autoimmune diseases. The presence of iron-deficiency anemia and thyroxine absorption issues should encourage further diagnostic workup.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hashimoto thyroiditis is a lifelong disorder with no cure; thus, it is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an endocrinologist, primary care provider, and an internist. The key is to follow up on the levels of thyroid hormone. Empirically prescribing one standard dose of levothyroxine may lead to hormone toxicity in some people. In addition, some patients may develop lymphoma, and thus a regular examination of the neck area is highly recommended.