Continuing Education Activity

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a low-grade, rapidly growing, 1 to 2 cm dome-shaped skin tumor with a centralized keratinous plug. Over the past hundred years, this tumor has been reclassified and reported differently throughout literature. Before 1917, keratoacanthoma were regarded as skin cancer. In the 1920s, reports labeled the tumor as verrucae or vegetating sebaceous cyst. Between 1936 and the 1950s the lesion was labeled and reported in the literature as molluscum sebaceum. Keratoacanthoma is characterized by initial rapid growth followed by a period of variable tumor stability and spontaneous regression. Keratoacanthoma is further divided into different subtypes with different presentations. Subtypes include solitary keratoacanthoma, subungual keratoacanthoma, mucosal keratoacanthoma, giant keratoacanthoma, keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum, generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski, and multiple keratoacanthomas Ferguson-Smith syndrome. Although recognized as benign, KA shares histopathological features with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) requiring treatment. This activity reviews the management of keratoacanthoma and the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the pathologic features of a keratoacanthoma.

Outline the types of keratocanthoma.

Summarize the treatment options available for keratoacanthoma.

Review the management of keratoacanthoma and the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating this condition.

Introduction

Keratoacanthoma (KA) is a low-grade, rapidly growing, 1 to 2 cm dome-shaped skin tumor with a centralized keratinous plug. Over the past hundred years, this tumor has been reclassified and reported differently throughout literature. Before 1917, keratoacanthoma were regarded as skin cancer. In the 1920s, reports labeled the tumor as verrucae or vegetating sebaceous cyst. Between 1936 and the 1950s the lesion was labeled and reported in the literature as molluscum sebaceum.

Keratoacanthoma is characterized by initial rapid growth followed by a period of variable tumor stability and spontaneous regression. Keratoacanthoma is further divided into different subtypes with different presentations. Subtypes include solitary keratoacanthoma, subungual keratoacanthoma, mucosal keratoacanthoma, giant keratoacanthoma, keratoacanthoma centrifugum marginatum, generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Grzybowski, and multiple keratoacanthomas Ferguson-Smith syndrome. Although recognized as benign, KA shares histopathological features with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) requiring treatment.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Multiple etiologies have been suggested including ultraviolet (UV) radiation, exposure to chemical carcinogens, immunosuppression, use of BRAF inhibitors, genetic predisposition including mutations of p53 or H-Ras, viral exposure including human papillomavirus (HPV), and recent trauma or surgery to the location. Keratoacanthoma can be commonly associated with syndromes such as autosomal dominant Muir-Torre syndrome, autosomal dominant Ferguson-Smith syndrome, autosomal recessive xeroderma pigmentosum, X-linked dominant incontinentia pigmenti, autosomal dominant Witten-Zak. The rare sporadic pruritic generalized eruption of keratoacanthoma is known as generalized eruptive keratoacanthoma of Gryzbowski.[5][6][7][8]

Epidemiology

Keratoacanthomas are reported in all age groups although they rarely appear before the age of 20. The peak incidence of solitary keratoacanthoma is between 50 and 69 years of age. They occur more frequently in men with a male to female ratio of 2:1. The majority have been described in fair skin individuals with the highest rates found in those with Fitzpatrick I-III classification. Additionally, they occur more frequently in immunosuppressed individuals and are more locally invasive. Keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinoma share many epidemiological features.

Pathophysiology

Originating in the pilosebaceous unit, keratoacanthomas are derived from an abnormality leading to hyperkeratosis of the infundibulum. Although associated with hair-bearing areas and sunlight, these tumors can develop in other areas including within the mouth, lip, gingiva, hard palate, and other mucosal surfaces. There are 3 stages of keratoacanthomas. These stages include proliferation, maturation, and involution. In the proliferative phase, rapid growth occurs up to approximately 6 to 8 weeks. The maturation phase lasts several weeks to months where the keratoacanthoma maintains its crateriform appearance. Involution is the final stage where the keratoacanthoma regresses into an atrophic scar. Stages are variable in length of time. Ultraviolet light, trauma, human papillomavirus (HPV), genetic factors, immune status, use of hedgehog pathway inhibitors for basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and use of BRAF inhibitors in patients with melanoma have been implicated as risk factors.

Histopathology

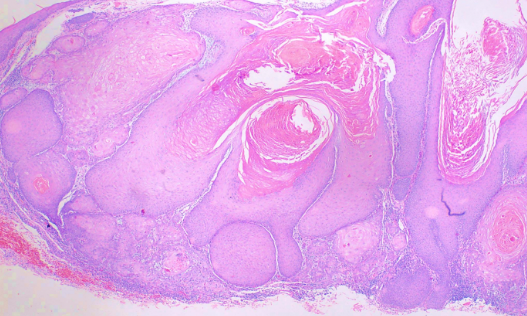

Considered by some to be a highly differentiated form of squamous cell carcinoma, histological examination reveals a circumscribed proliferation of well-differentiated keratinocytes (see Image. Keratoacanthoma). This has been described as multilobular exophytic or endophytic cyst-like invagination of the epidermis. The epidermis extends over the tumor, and there is a central horn plug of keratin. Peripheral to the keratin-filled crater are lip-like, peripheral borders of the epidermis. Intraepidermal neutrophilic abscesses are visualized in addition to horn pearls. The cells of the keratoacanthoma tumor are enlarged and atypical keratinocytes. They have a cytoplasm described as eosinophilic. Due to 3 stages of solitary keratoacanthoma, the histological examination can vary between stages. In comparison to squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma has intraepidermal microabscesses and tissue eosinophilia more commonly found. Recently keratoacanthoma has been reclassified as squamous cell carcinoma keratoacanthoma type (SCC-KA).[9]

History and Physical

Most occur on sun-exposed hair-baring areas with the face, head, neck, and dorsum of extremities. Lesions on the trunk are uncommon. Lesions begin as a small, round pink or skin-colored, papule that undergoes rapid growth to a dome-shaped nodule with a central keratin plug giving it a crateriform appearance. The classic size is 1 to 2 cm. It should be noted that keratoacanthoma may be seen in areas without sun exposure including the mucosal surfaces, subungual areas, buttocks, and anus. Physical examination should include regional lymph node examination due to the chance of invasion and metastases. Examination with dermoscopy cannot reliably distinguish between keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma; however, it can be used to distinguish both from other raised non-pigmented skin lesions. In particular, blood spots, white circles, and keratin are useful clues for distinguishing the lesion. White circles had the highest specificity.

Evaluation

Lesions are evaluated with a careful history and physical examination. A biopsy may be performed to evaluate with a histological exam. The best diagnostic test is an excisional biopsy as a shave biopsy may be insufficient to examine the depth to differentiate keratoacanthoma from squamous cell carcinoma. For patients with subungual keratoacanthomas, radiographic imaging is necessary of the affected digit in order to monitor for osteolysis.

Treatment / Management

While keratoacanthoma is recognized as benign, treatment is recommended due to the relation to squamous cell carcinoma. Treatment of choice consists of an excisional procedure with 4 mm margins. Lesions less than 2 cm on the extremities may be treated with electrodessication and curettage. Aggressive large tumors that are greater than 2 cm in cosmetically sensitive areas require tissue sparing and should consider Mohs micrographic surgery. For those with perineural invasion, Mohs micrographic surgery is the treatment of choice. Nonsurgical interventions have been limited to case reports and retrospective reviews consisting of topical 5% imiquimod cream, topical 5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream, intralesional methotrexate injections, intralesional bleomycin, intralesional 5-FU, and oral isotretinoin. Of the intralesional therapy, 5-FU and methotrexate have the most data. Intralesional 5-FU have been administered at a dose of 40 to 75 mg weekly for 3 to 8 weeks. Some data supports a 98% response rate. A case series for intralesional methotrexate have been in smaller numbers of patients but noted regression in 83% to 100% of patients.[10][11][12]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of a lesion consistent with a keratoacanthoma includes squamous cell carcinoma, amelanotic melanoma, molluscum contagiosum, prurigo nodularis, metastatic lesion to the skin, Merkel cell carcinoma, nodular basal cell carcinoma, ulcerative basal cell carcinoma, nodular Kaposi sarcoma, hypertrophic lichen planus, deep fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, foreign body reaction, and verruca vulgaris.

Prognosis

Keratoacanthoma has an excellent prognosis following surgical excision. Generally, patients with keratoacanthoma will have a history of sun exposure and will need to be followed for the development of new primary skin cancers. Metastases are rare, but there are reports of this in addition to perineural spread in literature.

Pearls and Other Issues

Keratoacanthomas of the neck and face have the potential to metastasize.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of keratoacanthoma is with an interprofessional team that includes the nurse practitioner, pathologist, dermatologist, primary care provider, and ENT surgeon. Once the diagnosis is made, treatment may vary from excision, laser, electrodesiccation, and curettage. When these lesions occur on the face, a consult from a plastic surgeon should be sought. There are several topical medications that can be used to treat keratoacanthoma, but the treatment is often long term, associated with skin discoloration and pain.

Keratoacanthoma has an excellent prognosis following surgical excision. Generally, patients with keratoacanthoma will have a history of sun exposure and will need to be followed for the development of new primary skin cancers. Metastases are rare, but there are reports of this in addition to perineural spread in literature. [13][14] (Level V)The primary care provider should educate the patient about sun exposure and protecting the skin. In addition, the patient should be told to wear sunscreen and protective garments when going outdoors.