Introduction

The pancreas is an extended, accessory digestive gland that is found retroperitoneally, crossing the bodies of the L1 and L2 vertebrae on the posterior abdominal wall. The pancreas lies transversely in the upper abdomen between the duodenum on the right and the spleen on the left. It is divided into the head, neck, body, and tail. The head lies on the inferior vena cava and the renal vein and is surrounded by the C loop of the duodenum. The tail of the pancreas extends up to the splenic hilum. The pancreas produces an exocrine secretion (pancreatic juice from the acinar cells) which then enters the duodenum through the main and accessory pancreatic ducts and endocrine secretions (glucagon and insulin from the pancreatic islets of Langerhans) that enter the blood.

Structure and Function

Divisions

The pancreas is divided into 4 parts: head, neck, body, and tail.

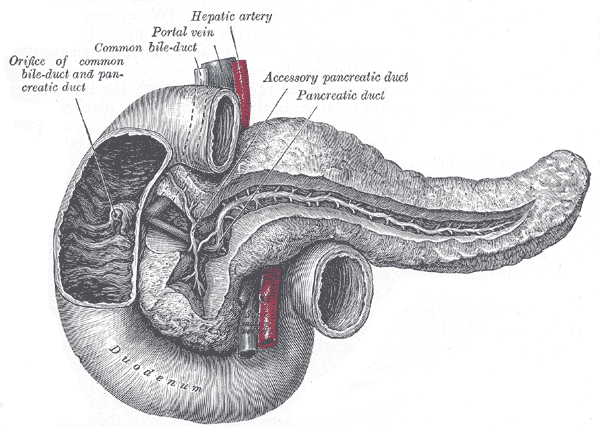

The head of the pancreas is the enlarged part of the gland surrounded by the C-shaped curve of the duodenum. On its way to the descending part of the duodenum, the bile duct lies in a groove on the posterosuperior surface of the head or is embedded in its substance. The body of the pancreas continues from the neck and passes over the aorta and L2 vertebra. The anterior surface of the body of the pancreas is covered with peritoneum. The posterior surface of the body is devoid of peritoneum. It is in contact with the aorta, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), the left suprarenal gland, the left kidney, and renal vessels.

The neck of the pancreas is short. The tail of the pancreas lies anterior to the left kidney, closely related to the splenic hilum and the left colic flexure. The main pancreatic duct carrying the pancreatic secretions joins with the bile duct to form the hepatopancreatic ampulla, which opens into the descending part of the duodenum. The hepatopancreatic sphincter of Oddi around the hepatopancreatic ampulla is a smooth muscle sphincter that controls the flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the ampulla and inhibits reflux of duodenal substances into the ampulla.

Cell Types

The majority of the pancreas (approximately 80%) is made up of exocrine pancreatic tissue. This is made of pancreatic acini (pyramidal acinar cells with the apex directed towards the lumen). These contain dense zymogen granules in the apical region, whereas the basal region contains the nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum (which aids in synthesizing the digestive enzymes). These enzymes are stored in secretory vesicles called the Golgi complex. The basolateral membrane of the acinar cells contains several receptors for neurotransmitters including secretin, cholecystokinin, and acetylcholine, which regulate exocytosis of the digestive enzymes.

The pancreas also contains the islet of Langerhans, which contain the endocrine cells. Unlike the exocrine enzymes, which are secreted by exocytosis, the endocrine enzymes enter the bloodstream via a complex capillary network within the pancreatic blood flow. There are 4 types of endocrine cells (A cells produce glucagon, B cells produce insulin, D cells produce somatostatin, and F cells produce pancreatic polypeptide).

Stellate cells are a direct formation of epithelial structures within the pancreas. In conditions like chronic pancreatitis, these cells promote inflammation and fibrosis.

Embryology

Development

The pancreas develops from the posterior foregut endoderm. At about 4 weeks gestation, this endoderm first gives rise to dorsal and ventral buds, which gradually elongate.[1] Around week 6, the ventral bud rotates around the then developing duodenum and eventually fuses with the dorsal bud at about the 17th week of gestation to form the pancreas. The dorsal bud thus forms the upper part of the pancreatic head, the body, and the tail, whereas the ventral bud forms the lower part of the pancreas and the uncinate process.

The pancreatic enzymes are drained by 2 pancreatic ducts: the duct of Wirsung (major pancreatic duct) and the duct of Santorini (minor pancreatic duct). The ventral duct forms the proximal portion of the major pancreatic duct, which opens into the duodenum via the ampulla of Vater. The dorsal duct forms a part of the major ducts as well as the minor duct or the accessory duct of Santorini. The latter usually empties through the ampulla of Vater but may empty independently in approximately 5% of people.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Supply

Branches of the splenic artery (a branch of the celiac trunk), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and the common hepatic artery provide blood supply to the pancreas.[2][3]

- Pancreatic head: The gastroduodenal artery (a branch of the common hepatic artery) supplies the head and the uncinate process of the pancreas in the form of the pancreaticoduodenal artery (PDA). Part of the inferior portion of the head is supplied by the inferior PDA, which arises from the SMA.

- Body and the tail: The splenic artery and its branches supply these.

Venous Supply

- Pancreatic head: The head drains into the superior mesenteric vein (SMV).

- Body and the neck: The splenic vein drains these.

The SMV and splenic vein merge to form the portal vein.

Nerves

The pancreas has a complex network of parasympathetic, sympathetic, and sensory innervations.[4] It also has an intrinsic nerve plexus. Sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers are dispersed to pancreatic acinar cells. The parasympathetic fibers arise from the posterior vagal trunk and are secretomotor, but the secretions from the pancreas are predominantly mediated by cholecystokinin and secretin, which are hormones produced by the epithelial cells of the duodenum and proximal intestinal mucosa regulated by acidic compounds from the stomach. Sympathetic innervation is via the T6-T10 thoracic splanchnic nerves and the celiac plexus.

Physiologic Variants

- Partial or dorsal agenesis of the pancreas is often asymptomatic. It is sometimes associated with diabetes, polysplenia, malabsorption syndrome, or recurrent pancreatitis.

- Ectopic pancreatic tissue is present in the stomach (most common) or small intestine. This is seen in about 3% to 5% of the general population and is usually an incidental finding on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or a barium contrast study. Their umbilicated appearance typically identifies them, and they are most commonly clinically insignificant. Very rarely, a pancreatic rest in the small intestine may be the lead point of intussusception or may cause bowel obstruction.

- Pancreas divisum is the most common developmental anomaly of the pancreas [5]. It occurs in about 10% to 15% of the general population. It occurs as the result of the failure of the pancreatic buds to fuse. Thus the tail, body, and part of the head of the pancreas drain through the accessory duct of Santorini instead of the major duct. Pancreatic divisum has been historically associated with recurrent pancreatitis, and it is hypothesized that this could be due to stenosis of the sphincter leading to obstruction of the outflow of the ventral pancreas. A divisum is diagnosed by an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Lately, endoscopic ultrasound is used to diagnose a pancreatic divisum. In case of recurrent pancreatitis, the pancreas divisum is treated by insertion of a stent via ERCP as well as a sphincterotomy.

- Pancreatic dysgenesis/dysfunction is a component of certain syndromic associations, including Johanson-Blizzard and Schwachmann-Diamond syndromes.

Surgical Considerations

Annular pancreas results when the ventral bud fails to rotate completely during development [5]. This may occur due to certain autosomal recessive mutations. Patients usually present in infancy with a bowel obstruction (complete or partial). There is often a history of maternal polyhydramnios. Annular pancreas is often associated with other anomalies, including trisomy 21, tracheoesophageal fistula (VACTERL), malrotation, and cardiac or renal abnormalities. The annular pancreas can be associated with pancreatitis as well. This condition is usually treated with duodenojejunostomy.

Choledochal cysts are dilations of the biliary tract. This usually presents as jaundice and abdominal pain. Fever can be seen in some cases. Laboratory evaluation will demonstrate elevated direct bilirubin levels with normal transaminases. The condition is usually diagnosed via imaging: ultrasonography, CT, HIDA scan, or MRCP.

Clinical Significance

Perforation

Perforation of the pancreas results in the secretion of digestive enzymes such as amylase and lipase into the abdominal cavity and pancreatic self-digestion. While it is possible to remove the pancreas surgically, the individual will face a lifetime of blood glucose regulation and pancreatic enzyme supplements needed to aid digestion.

Cancer

Pancreatic cancers, particularly pancreatic adenocarcinoma, are very difficult to treat and are usually diagnosed at a stage too late for surgery. Pancreatic cancer is rare in younger patients; the median age of diagnosis is 71. Risk factors include smoking, obesity, diabetes, and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer.

Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1

Diabetes mellitus type 1 is an autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas resulting in decreased insulin. Type 1 diabetes usually develops in childhood. Patients with type 1 diabetes require insulin injections for survival.

Type 2

Diabetes mellitus type 2 is the most common form of diabetes. The disease causes high blood sugar, usually due to a combination of insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion. Treatment includes changes in diet and physical activity as well as biguanides such as metformin.

Inflammation

Pancreatic inflammation is known as pancreatitis. It is associated with recurrent gallstones, alcohol use, measles, mumps, medications, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and scorpion stings.

Pancreatitis causes intense pain in the central abdomen that radiates to the back. It may be associated with jaundice. Pancreatitis often presents with pale stools and dark urine.