[2]

Ivanchina AE, Kopylov FY, Volkova AL, Samojlenko IV, Syrkin AL. [Clinical Value of Algorithms of Minimization of Right Ventricular Pacing in Patients With Sick Sinus Syndrome and History of Atrial Fibrillation]. Kardiologiia. 2018 Aug:(8):58-63

[PubMed PMID: 30131043]

[3]

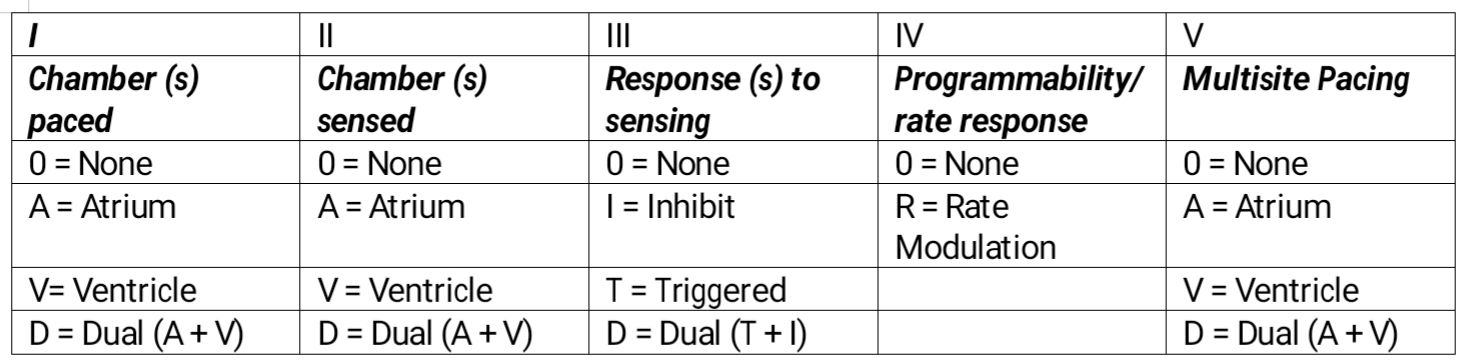

Bernstein AD, Daubert JC, Fletcher RD, Hayes DL, Lüderitz B, Reynolds DW, Schoenfeld MH, Sutton R. The revised NASPE/BPEG generic code for antibradycardia, adaptive-rate, and multisite pacing. North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology/British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE. 2002 Feb:25(2):260-4

[PubMed PMID: 11916002]

[4]

Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, DiMarco JP, Dunbar SB, Estes NA 3rd, Ferguson TB Jr, Hammill SC, Karasik PE, Link MS, Marine JE, Schoenfeld MH, Shanker AJ, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Stevenson WG, Varosy PD, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Jan 22:61(3):e6-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.007. Epub 2012 Dec 19

[PubMed PMID: 23265327]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[5]

2012 Writing Group Members, Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, DiMarco JP, Dunbar SB, Estes NA 3rd, Ferguson TB Jr, Hammill SC, Karasik PE, Link MS, Marine JE, Schoenfeld MH, Shanker AJ, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Stevenson WG, Varosy PD, 2008 Writing Committee Members, Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, ACCF/AHA Task Force Members, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Creager MA, DeMets D, Ettinger SM, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson W, Yancy CW, American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Heart Failure Society of America, Society of Thoracic Surgeons. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2012 Dec:144(6):e127-45. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.032. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23140976]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[6]

Van Gelder IC, Rienstra M, Crijns HJ, Olshansky B. Rate control in atrial fibrillation. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Aug 20:388(10046):818-28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31258-2. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27560277]

[7]

Mattsson G, Magnusson P. [The leadless pacemaker system: present applications and future perspectives]. Lakartidningen. 2018 Aug 8:115():. pii: E7UM. Epub 2018 Aug 8

[PubMed PMID: 30106456]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Tjong FVY, Beurskens NEG, Neuzil P, Defaye P, Delnoy PP, Ip J, Guerrero JJG, Rashtian M, Banker R, Reddy V, Exner D, Sperzel J, Knops RE, Leadless II IDE and, Observational Study Investigators. The learning curve associated with the implantation of the Nanostim leadless pacemaker. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2018 Nov:53(2):239-247. doi: 10.1007/s10840-018-0438-8. Epub 2018 Aug 13

[PubMed PMID: 30105428]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[9]

Stone ME, Salter B, Fischer A. Perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. British journal of anaesthesia. 2011 Dec:107 Suppl 1():i16-26. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer354. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22156267]

[10]

Zhang S, Gaiser S, Kolominsky-Rabas PL, National Leading-Edge Cluster Medical Technologies “Medical Valley EMN”. Cardiac implant registries 2006-2016: a systematic review and summary of global experiences. BMJ open. 2018 Apr 12:8(4):e019039. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019039. Epub 2018 Apr 12

[PubMed PMID: 29654008]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[11]

Magnusson P, Liv P. Living with a pacemaker: patient-reported outcome of a pacemaker system. BMC cardiovascular disorders. 2018 Jun 4:18(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12872-018-0849-6. Epub 2018 Jun 4

[PubMed PMID: 29866050]

[12]

Thanavaro JL. Cardiac risk assessment: decreasing postoperative complications. AORN journal. 2015 Feb:101(2):201-12. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2014.03.014. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25645037]

[13]

Knight BP, Gersh BJ, Carlson MD, Friedman PA, McNamara RL, Strickberger SA, Tse HF, Waldo AL, American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias), Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, Heart Rhythm Society, AHA Writing Group. Role of permanent pacing to prevent atrial fibrillation: science advisory from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias) and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2005 Jan 18:111(2):240-3

[PubMed PMID: 15657388]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[14]

Bodagh N, Pappa E, Farooqi F. Multidisciplinary surgical team approach for excision of squamous cell carcinoma overlying pacemaker site. BMJ case reports. 2018 Feb 6:2018():. pii: bcr-2017-221660. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-221660. Epub 2018 Feb 6

[PubMed PMID: 29437678]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence