Introduction

The scrotum is a male reproductive structure located under the penis. It has the shape of a sac and divides into two compartments. The structures contained in this sac include external spermatic fascia, testes, epididymis, and spermatic cord. The scrotum derives from the labioscrotal swelling, which is an embryonic structure that appears in the fourth week of embryonic development. Congenital malformations may occur during the development of the scrotum. These malformations can present in conjunction with other defects due to a common embryologic origin.

Structure and Function

Structure:

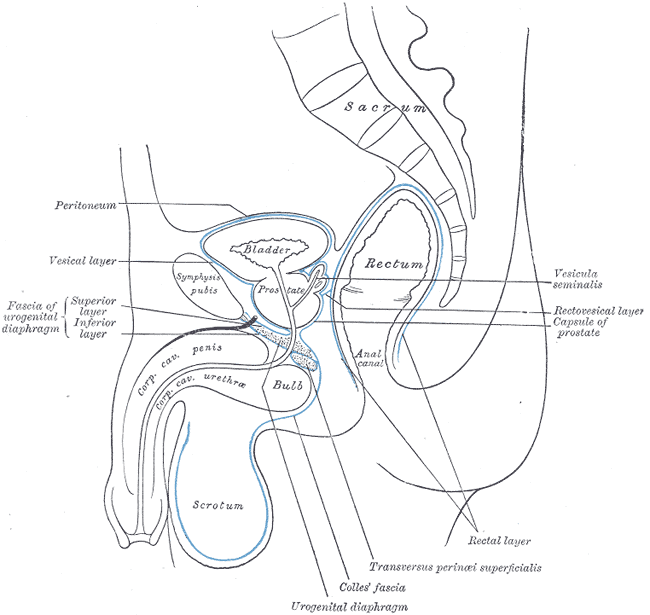

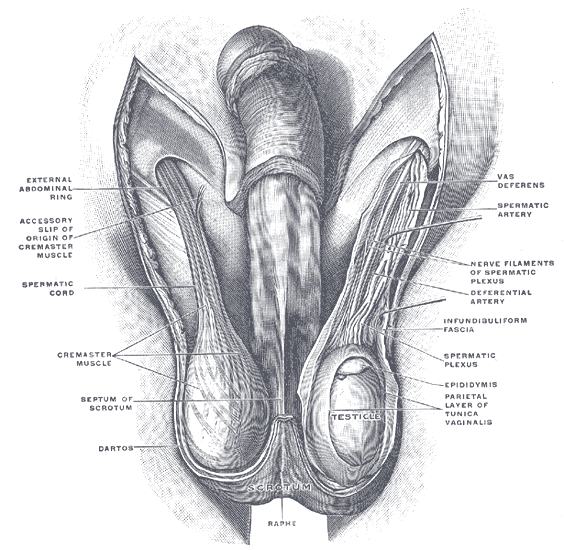

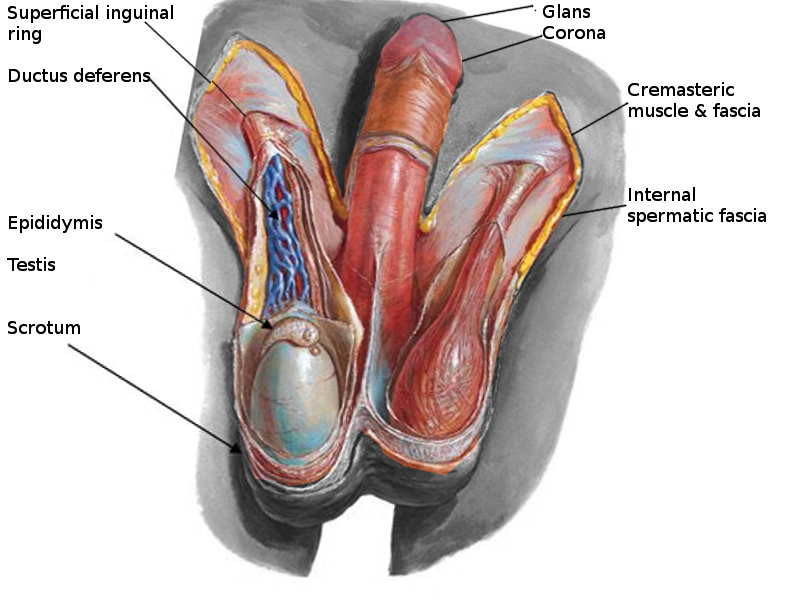

The scrotum is a thin external sac that is located under the penis and is composed of skin and smooth muscle. This sac is divided into two compartments by the scrotal septum. The average wall thickness of the scrotum is about 8 mm. It has a parietal and a visceral layer. The parietal layer has the function of covering the inner aspect of the scrotal wall and the visceral layer coats the testis and epididymis. The structures contained in the scrotal sac are the external spermatic fascia, testes, epididymis, and spermatic cord.

Function:

The scrotum is responsible for protecting the testes. It helps with the thermoregulation of the testicles. It keeps the temperature of the testis several degrees below the average body temperature, which is an essential factor for sperm production.

Embryology

The labioscrotal swellings are the structures that appear during the fourth week of gestations and give origin to the scrotal tissue. These two structures are present lateral to the genital tubercle. The migration of the labioscrotal swellings takes place in the 9th to 11th weeks of gestation and follows in a caudal and medial direction until they fuse at the 12th-week of gestation and form the scrotum.[1][2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply:

Arteriovenous anastomoses and subcutaneous plexuses are responsible for providing blood supply to the scrotum. The external pudendal branches arising from the femoral arteries and the scrotal branches of the in the internal pudendal arteries play a significant role in supplying blood to the scrotum. The nomenclature of the venous drainage of the scrotum mirrors the previously mentioned corresponding arteries.

Lymphatic drainage:

The arrangement of the lymphatic drainage of the scrotum is related to the development of this sac. The wall of the scrotum drains into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. On the other hand, the contents of the scrotum drain to the lumbar lymph nodes. It is important to recall that the testes migrate from the abdominal wall through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. During this path, the testis will drag its blood supply and lymph vessels into the scrotal sac.[3]

Nerves

The innervation of the scrotum derives from the branches of the following four nerves: genitofemoral, pudendal, posterior femoral cutaneous, and ilioinguinal nerves.

Anterior Innervation:

The cremaster muscle and anterior scrotum receive their innervation by the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. This nerve arises from the L1-L2 segments of the lumbosacral plexus and then travels through the inguinal canal to supply the anterior skin of the scrotum.

Posterior Innervation:

The posterior scrotum is innervated by branches of the pudendal nerve and by the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve.

The ilioinguinal nerve also aids the genitofemoral nerve in the innervation of the cremasteric muscle.

Cremasteric Reflex:

Both the ilioinguinal and the genitofemoral nerves provide a sensory synapse that activates the motor neurons responsible for the cremasteric reflex.[4] This physiologic reflex has both protective and thermoregulatory testicular functions.[5]

Muscles

The scrotum is a fibromuscular structure. The muscle fibers contained in the scrotum are the dartos muscle and the cremasteric muscle. The dartos muscle is a smooth muscle sheet located underneath the skin of the scrotum. The cremasteric muscle is a paired muscle that has many protective functions. This paired muscle is composed of two parts, a medial cremaster portion originating from the pubic tubercle and the lateral cremaster portion originating from the internal oblique muscle.

Physiologic Variants

The scrotum may present with congenital malformations that are due to abnormal development of the labioscrotal swellings, which occur during intrauterine development. These malformations may include accessory scrotum, bifid scrotum, ectopic scrotum, and penoscrotal transposition.

Accessory Scrotum:

It is the rarest of congenital abnormalities of the scrotum. Although exact etiology is not clear, it is thought to occur due to the abnormal migration of labioscrotal swellings during the 4th to 12th weeks of development. The most common location of an accessory scrotum is mid perineum. The accessory scrotum does not contain testes. This additional tissue will have the same histologic features present in a typically developed scrotum and does not interfere with the development of the customarily positioned scrotum.[1][6]

Bifid Scrotum:

A bifid scrotum is an abnormal cleft that presents in the midline of the scrotum. This cleft is caused by an incomplete fusion of the labioscrotal folds. The incomplete fusion can be attributed to an under-secretion of androgens during the first trimester. This androgenic under-secretion can also cause hypospadias and maybe the reason why most patients that are born with a bifid scrotum also present with hypospadias.[7]

Ectopic Scrotum:

An ectopic scrotum occurs when the normal scrotum that is usually located under the penis is found in a different location. The main factor of this abnormality is a defect in the formation of the gubernaculum. The most common sites in which you can find an ectopic scrotum include a suprainguinal, inguinal, infra-inguinal, or perineal region.

Penoscrotal Transposition:

This condition is a genital malpositioning in which the penis is lying in an abnormal location in relation to the scrotum. This rare malformation is due to a defect of the scrotum during its caudal migration in the 9th to 11th week of gestation. This inversion can be classified as either partial or complete. A partial transposition occurs when the penis lies in the middle of the scrotum. A complete penoscrotal transposition, on the other hand, is seen when the penis emerges beneath the scrotum. The literature has shown that this anomaly can present in conjunction with central nervous system, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal tract congenital malformations[2]

Surgical Considerations

Cryptorchidism:

One of the most common neonatal malformations is an undescended testicle. It occurs in about 2-4% of male neonates. Given the numerous associated complications of cryptorchidism, those patients with failure of the testes to spontaneously descend require a surgical repair called orchiopexy. The traditional approach of the orchiopexy is by making an inguinal incision. Given the numerous structures that can suffer injury through this incision, a trans scrotal approach was introduced. The advantages of this effective technique include uncomplicated dissection, better wound healing, and shorter operation time. The disadvantages of this approach include wound infections, testicular hypotrophy, hydrocele, and hernias.[8]

Testicular Torsion:

Testicular torsion is a vascular emergency defined as a rotation of the spermatic cord that causes strangulation of the testicular artery, which leads to loss of blood supply to the testicle. This pathology requires a prompt surgical approach. A defect in embryologic development of the tunica vaginalis is mainly responsible for testicular torsion. Patients with testicular torsion may present with acute pain, nausea, and vomiting. Testicular torsion should be approached urgently, given that after the first 24 hours of the loss of blood supply, the tissue can suffer necrosis. Once the tissue is necrotic, there is very little likelihood of saving the testis.[3]

Hematocele:

Hematocele is a blood collection in the scrotum that can be associated with a traumatic injury or a surgical procedure. It can be diagnosed using a scrotal ultrasound. This blood collection usually self resolves, but in rare cases, it may develop calcifications, which are extra-testicular lesions palpated on physical exams.[9][10]

Clinical Significance

The genitourinary male physical examination has great significance in diagnosing many pathologies. Some of the clinical diseases that may show local signs detected on a physical exam are noninflammatory edema, cellulitis, and Fournier gangrene.

Noninflammatory Edema:

Noninflammatory edema may be visible on a scrotal ultrasound as a fluid collection that is not associated with scrotal wall hyperemia. The pathophysiology attributed to this edema could be heart failure, liver failure, lymphatic obstruction, or a fluid imbalance.

Cellulitis:

Cellulitis should be included in the differential diagnoses in any patient presenting with scrotal pain and a thickened erythematous scrotum on a physical exam. This diagnosis should be considered in any patient with a past medical history of immunosuppression, diabetes, or obesity, presenting with local signs of inflammation in the scrotum.

Infectious Diseases:

Many microorganisms can colonize in the scrotum and cause an infection. From the components of the scrotum, the tail of the epididymis is one of the first sites of infections, given that it is the most vascularized portion of the scrotum. Any infection originating from a surrounding anatomical structure can migrate and eventually infect the scrotum. The most common microorganisms infecting the scrotum are bacterial pathogens, among which Escherichia coli, Proteus, Neisseria gonorrhea, and Chlamydia trachomatis predominate.