Introduction

The pupillary dilation pathway is a sympathetically driven response beginning in the hypothalamus and ending with the contraction of the dilator pupillae muscle. It is for this reason that pupillary dilation may result from any physical or emotional stress that triggers the autonomic sympathetic nervous system, which is mediated by the hypothalamus.

The pupillary dilation pathway is a three-neuron pathway; disruptions anywhere along the oculosympathetic pathway may cause Horner syndrome, which is a classic triad of ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis of the face due to loss of sympathetic innervation. It is essential to avoid damaging the superior cervical ganglion during cervical surgery, as such damage could prompt the development of Horner syndrome.

Although Horner syndrome is predominantly a clinical diagnosis, in more subtle cases, administration of topical cocaine to the eye for confirmation secondary to cocaine's sympathetically activating qualities is an option. One of cocaine's mechanisms of action is to block the reuptake of norepinephrine at the neuromuscular junction. Topical cocaine in a person without Horner's syndrome will cause pupillary dilatation. Topical cocaine in a person with Horner syndrome will lead to minimal or no dilation at all. In addition to Horner syndrome, chronic opiate abuse can cause miosis.

Structure and Function

The pupillary dilation pathway is a sympathetically driven response to stimuli and is a three-neuron pathway.[1] The first-order neuron begins in the hypothalamus and descends through the midbrain to synapse onto the spinal cords ciliospinal center of Budge, found between C8 to T2. The second-order neuron, the preganglionic sympathetic neuron, exits the spinal cord through the ventral roots and ascends through the thorax, near the lung apex and subclavian vessels, onto the superior cervical ganglion.

The superior cervical ganglion appears opposite the second and third cervical vertebrae, near the angle of the mandible and the bifurcation of the common carotid artery.[2] The third-order postganglionic neurons travel along the periarterial carotid plexus through the cavernous sinus. These axons then enter the orbit upon the short and long ciliary nerves (branches of V1, the ophthalmic division of CN V - the trigeminal nerve) to synapse on the dilator pupillae muscle, causing pupillary dilation.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the sympathetic chain and ganglia is primarily via the ascending pharyngeal artery, ascending cervical artery, thyrocervical trunk, and supreme intercostal arteries.[3] The internal jugular vein supplies the venous drainage to this region. As the pathway ascends past the superior cervical ganglion, the blood supply is from the internal carotid artery, followed by the ophthalmic artery. Additionally, as the pathway ascends, lymphatic drainage follows regional lymph nodes.

Surgical Considerations

Any disruption along the three neuron pathways can result in loss of pupillary dilation. Although rare, damage to the superior cervical ganglion can occur as a complication of anterior or posterior cervical spine surgery, or surgery involving the thoracic outlet or lung apex. This damage presents as an abnormally small pupil with the inability to dilate due to the disruption of the cervical sympathetic nerves, known as Horner’s syndrome.[1] Horner syndrome is a classic triad of ipsilateral ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis of the face due to the disruption of the sympathetic pathway in the head and neck.

Although the diagnosis of Horner syndrome is predominantly clinical, in subtle cases, confirmation is possible by applying topical cocaine eye drops.[4] Cocaine is a stimulant that activates the sympathetic nervous system and acts by blocking the reuptake of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin at the synaptic cleft. Since pupillary dilation is a sympathetic function, a classic sign of cocaine and other stimulant use is dilated pupils. If there is a disruption of the pupillary dilation pathway, in this case, via damage to the superior cervical ganglion, applying cocaine eye drops to the ipsilateral eye will not produce pupillary dilation. Therefore, in the presence of the triad mentioned above, if there is no pupillary dilation with the administration of cocaine eye drops, Horner’s syndrome can be confirmed.

Of note, apraclonidine eye drops are also an option in the place of cocaine eye drops.[5] Horner syndrome can also occur secondary to a variety of causes, located anywhere along the pupillary dilation pathway. These include dissection of the carotid artery,[6] brachial plexus injury, neck mass, cervicothoracic spinal lesion, and Pancoast tumors, among many others.

Clinical Significance

Clinically, monitoring pupil dilation is intrinsic to the management of opioid overdose. According to the CDC’s 2018 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes, although opioid prescribing has continued to decrease through 2017, drug overdose deaths in the United States reached a record high in 2016 of 63,632.[7] Of these fatalities, 66.4% involved opioids (42,249), the most common of which were synthetic opioids other than methadone (19,413), prescription opioids (17,087), and heroin (15,469). Amidst the opioid crisis, it is imperative to understand the treatment of opioid overdose.

Opioids are parasympathomimetics that act predominantly on mu receptors to produce feelings of euphoria, analgesia, and sedation. In toxic doses, opioids cause depressed mental status, respiratory depression (<12/min), decreased tidal volume, and pupillary constriction, or miosis. Due to respiratory depression, initial management should focus on airway and breathing, with preparation to mechanically ventilate if it becomes necessary. These measures are closely followed by the administration of naloxone, ideally via the intravenous route, which is a short-acting pure opioid antagonist.

Naloxone has a duration of approximately two hours, and repeat administration may be necessary if respiratory depression and coma return, especially if the patient ingested a long-acting opioid. Since naloxone reverses pupillary constriction, administration via injection can continue until pupillary dilation takes place. Similarly, the clinical team can monitor the size of the patient’s pupils to assess whether a subsequent dose is necessary, although monitoring of pupils should take place in conjunction with observation for the return of respiratory depression. Of note, naloxone is available OTC in many states, and expanded access to naloxone is essential for reducing opioid overdose morbidity and mortality.[8]

Another common clinical scenario associated with pupillary dilation is an uncal brain herniation, a complication of high intracranial pressure in which a portion of the temporal lobe herniates over the tentorium and places pressure on the midbrain. However, the associated pupillary dilation is not from the activation of the pupillary dilation pathway. Instead, it is from compression of the oculomotor nerve, which causes altered parasympathetic input to the ipsilateral eye.[9] Since pupillary constriction occurs parasympathetically, parasympathetic paralysis results in loss of pupillary constriction and hence, pupillary dilation.

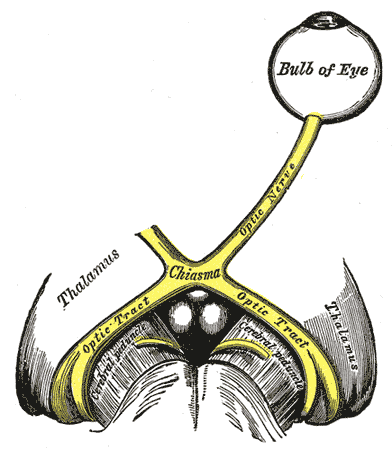

Additionally, pupillary dilation as an adaptation to low levels of light is due to the pupillary light reflex, in which varying intensities of light fall on the retinal ganglion cells and cause pupillary constriction or dilation; this is a separate pathway from the pupillary dilation pathway.