Continuing Education Activity

The West Nile virus is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA arbovirus that can cause disease in humans. These range from the asymptomatic infected patient to fever and malaise to florid neurological deficits secondary to encephalitis and neuroinvasive disease. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of infection from West Nile virus and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in collaborating to provide care for the treatment of this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the epidemiology of West Nile virus infection.

- Describe an appropriate history and physical examination findings for someone with West Nile fever and with neuroinvasive West Nile virus.

- List the means of diagnosis along with the treatment and management options available for patients with West Nile virus.

- Summarize interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to advance the treatment of West Nile virus and improve outcomes.

Introduction

West Nile virus is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus and member of the Flaviviridae family. It is an arbovirus transmitted to humans by the bite of a mosquito.

It is known to cause disease in humans with a wide array of presentations. These range from the asymptomatic infected patient to fever and malaise to florid neurological deficits secondary to encephalitis. However, most people infected with West Nile virus are asymptomatic. Approximately 1 in 4 patients experience fever with symptoms of a viral syndrome, while around 1 in 200 develops neuroinvasive disease.[1][2]

Originally seen in Africa, West Nile virus began showing up throughout Europe, Asia, and North America in the 1990s. It is now present throughout much of the world.

Etiology

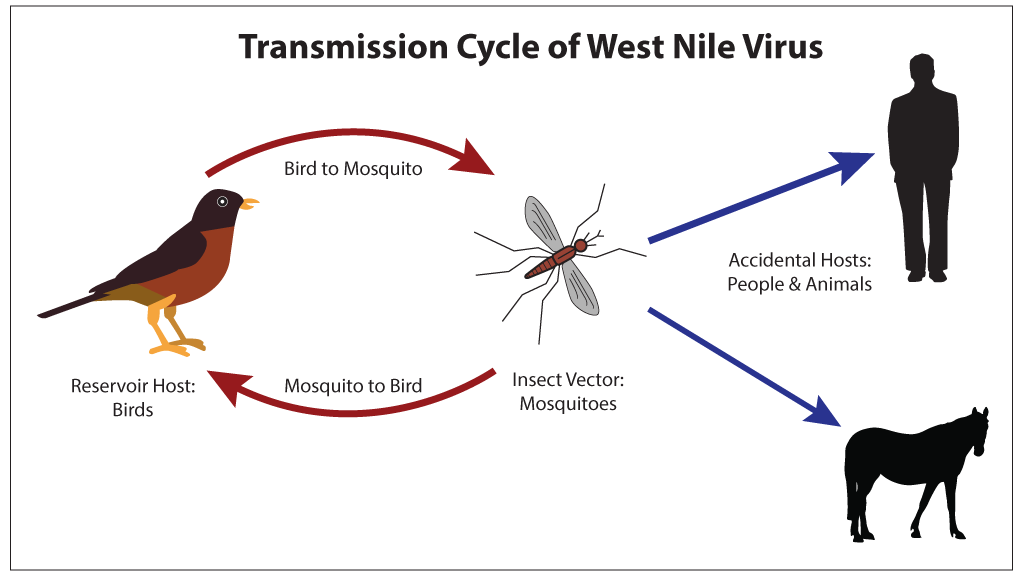

The West Nile virus infects humans following a mosquito bite. The Culex species of mosquito is the most common vector. Besides humans, the West Nile virus can infect birds, horses, dogs, and many other mammals. Wild birds may be the optimal hosts for harboring and enabling amplification of the virus. Humans are considered accidental dead-end hosts due to the low and transient viral levels in the bloodstream. Additional and rare means of transmission include infected donor blood, organs, breast milk, or transplacental infection.[3]

About 1% of individuals will develop serious symptoms and the overall morbidity is increased in people over the age of 50. The most common complications are neurological. Unfortunately, the lack of federal funding has meant that active surveillance of this virus is not maintained in many states.

Epidemiology

The first reports of West Nile virus were in Uganda in 1937. It resurfaced in 1999 when there were reports of seven deaths and 62 cases of encephalitis in New York; this was the first presentation of the virus in the western hemisphere. As of today, the West Nile virus is found in Africa, Europe, Asia, North America, Australia, and the Middle East.[4]

The original outbreaks of the virus showed a typically self-limited and minor illness. In the mid-1990s West Nile virus became correlated with severe neurologic disease. Based on a comprehensive literature review in 2013, meningitis and encephalitis (neuroinvasive disease) were present in less than one percent of infected patients with a mortality of 10 percent. West Nile fever is present in 25% of those infected; the remaining 75% show few to no symptoms. This fact leads to the likely vast underreporting of West Nile virus infections. Outbreaks tend to be associated late summer and fall due to the mosquito vector’s life cycle and the amplification from the bird-mosquito-bird cycle. In warmer climates, cases can occur throughout the year.[1]

In the US from 1999 to 2015, there have been almost 44000 confirmed and probable cases of West Nile virus with over 20000 cases of neuroinvasive disease. The number of neuroinvasive cases varies heavily year to year, ranging from 386 to 2946. Serologic surveys and blood donor screening data shows a rate of neuroinvasive disease of around 0.5% of infected patients and an infection rate of 10% in areas of outbreak. This data extrapolates to an estimated 3 to 5 million cases of infection.[5]

Pathophysiology

The virus is transmitted when the mosquito feeds, passing infected saliva into the host. The early phase following transmission includes viral replication in dermal dendritic cells and keratinocytes. This phase is followed by the visceral-organ dissemination phase, which includes viral replication in draining lymph nodes, viremia, and spread to the visceral organs. The third and final phase spreads to the central nervous system (CNS).

The mechanism for viral CNS entry is unclear but may include a direct crossing of the blood-brain barrier, passive transport through the endothelium, infected macrophages crossing the blood-brain barrier or direct axonal retrograde transport. Once in the CNS the virus primarily induces inflammation and a subsequent loss of neurons within the spinal cord and brainstem gray matter.[6][7]

History and Physical

The incubation period of the West Nile virus varies from 4-14 days.Symptoms tend to last 5-7 days and include fever in at least 1/4th of patients.

The clinical presentation of West Nile virus in most cases include myalgia, malaise, and a low-grade fever. Other associated symptoms include headache, eye pain, vomiting, anorexia, and up to 50% may have a maculopapular rash on the trunk appearing upon defervescence. However, in rare cases, the virus can cause neurologic symptoms, including severe muscle weakness, changes in mental status, seizures, or flaccid paralysis. These patients initially present with features of encephalitis and/or meningitis that progresses rapidly, and they require ICU care. Even with aggressive supportive treatment, the mortality rate following a case of neuroinvasive West Nile infection is high.

Most people infected with West Nile virus have a history of travel to an area where the virus is endemic during the summer or fall. However, this includes areas on most continents, as listed in the epidemiology section. The West Nile virus incubation period is two to 14 days. The typical infection includes a fever for five days, headache for 10 days and fatigue for around a month.[8]

Evaluation

Routine labs may reveal leukocytosis and other non-specific findings secondary to the viral infection. The diagnosis is via serologic detection of West Nile virus using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the IgM antibody in blood or CSF samples. A plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) can distinguish serologic cross-reactions.

Hyponatremia may be seen when the CNS is involved.

Neuroinvasive West Nile virus will typically have findings consistent with viral meningitis on lumbar puncture. Analysis of CSF shows elevated protein and leucocyte levels, with a possible predominance of neutrophils early, transitioning to a lymphocytic predominance accompanied by normal glucose levels. For neuroinvasive disease, the CSF should also be tested using the ELISA test. In patients with a high suspicion of viral infection and an initial negative test, a repeat should be performed 10 days later as IgM levels may take time to elevate to the levels necessary to be detectable.

Imaging: CT of the brain will typically not show any acute findings of the disease. MRI may show abnormalities after several weeks of acute neuroinvasive disease.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of West Nile virus is primarily supportive care. Researchers have tried several agents including interferon, ribavirin, and intravenous immunoglobulin. No clear efficacy data exists as only one controlled study has been performed to date.[9]

Once the clinician has made a diagnosis of West Nile virus, individuals with milder cases can be managed symptomatically as outpatients and tend to have an excellent prognosis. However, toxic patients with neurologic symptoms usually require long-term ICU care. These patients will typically require long-term physical and occupational therapy at rehabilitation centers. After the infection, neurologic injury from the West Nile virus may include gross motor, cognitive, and fine motor abnormalities. Many patients have residual neurologic deficits, which can take a long time to recover, and some deficits may be permanent.

When the CNS is involved, many patients become bed ridden and hence pressure sores, aspiration and DVT are common; thus prophylaxis is warranted.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential for the West Nile virus is extensive, and investigation should include a careful travel history[10]:

- Bacterial meningitis

- Varicella-zoster virus

- Herpes simplex type 1 virus

- St. Louis encephalitis – confirmatory testing required may cross-react

- Enteroviruses

- Dengue virus

- Japanese encephalitis

The differential also includes tickborne illnesses:

- Lyme disease

- Ehrlichiosis

- Anaplasmosis

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever

- Powassan virus

Prognosis

The prognosis for the vast majority of patients with West Nile virus (WNV) is excellent. Most infected patients are asymptomatic. Those who develop West Nile fever tend to have symptoms of a viral syndrome. It is a self-limited illness with most symptoms lasting up to 10 days. However, the rare and most serious clinical manifestation, neuroinvasive disease, has a mortality of approximately 10 percent. The geriatric population has the highest risk for neuroinvasive WNV. The neuroinvasive disease includes a wide spectrum of neurologic deficits, and some of these may persist for years or even become permanent.[11][12]

Severe disease tends to affect the elderly and the greatest risk factor for death is neurological involvement. Anywhere from 1-4% of patients who develop neurological problems may die.

Complications

- Neurologic symptoms

- Meningitis, encephalitis, weakness, neuropathy, acute flaccid paralysis, seizures, coma

- Ocular manifestations

- Vvitreitis, chorioretinitis, retinal hemorrhages

- Myocarditis

- Pancreatitis

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Central diabetes insipidus

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

Since WNV is transmitted almost exclusively through a mosquito vector, avoiding mosquito bites is the primary method of prevention.

Current methods of deterrence consist of two main components, personal protective measures and mosquito control. Insect repellants containing DEET or picaridin, permethrin-treated clothing, and avoiding exposure to endemic or high-risk areas with mosquitoes are the mainstays of personal protection. Mosquito control programs may also help decrease exposure along with reducing high-risk conditions, such as standing water around the home.[13]

Pearls and Other Issues

The prognosis after severe neuroinvasive WNV infection is often guarded. Most individuals require long-term rehabilitation, and some neurologic deficits may be permanent. There is no clear evidence for effective treatment beyond supportive care at this time.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

WNV infection is challenging to diagnose and can quickly progress to neurologically devastating and even fatal disease. This condition is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes an emergency medicine physician, an internist for inpatient management, a critical care physician if needing ICU management, an infectious disease physician, along with pharmacy and nursing support. The care is primarily supportive, and the diagnosis is often difficult to make due to the variable presentation and overall rarity of the disease. The patient’s primary care doctor, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner should dispense preventative education; this includes protecting exposed skin, the use of insect repellants, and avoiding high-risk areas.

Current methods of deterrence consist of two main components, personal protective measures and mosquito control. Insect repellants containing DEET or picaridin, permethrin-treated clothing, and avoiding exposure to endemic or high-risk areas with mosquitoes are the mainstays of personal protection. Mosquito control programs may also help decrease exposure along with reducing high-risk conditions, such as standing water around the home.[13]

To summarize, West Nile virus infection requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V]