Continuing Education Activity

The management of anorectal malformations is challenging and exceptionally complex. To achieve appropriate outcomes in children with this diagnosis, careful preoperative and surgical planning must be performed. Additionally, life long care and attention to bowel management is key to patient success. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the appropriate evaluation of a patient with an anorectal malformation.

- Describe the appropriate preoperative workup for a patient with an anorectal malformation.

- Describe the correct options for surgical management based on the type of anorectal malformation.

- Explain the importance of the interprofessional team in the delivery of care for patients with an anorectal malformation.

Introduction

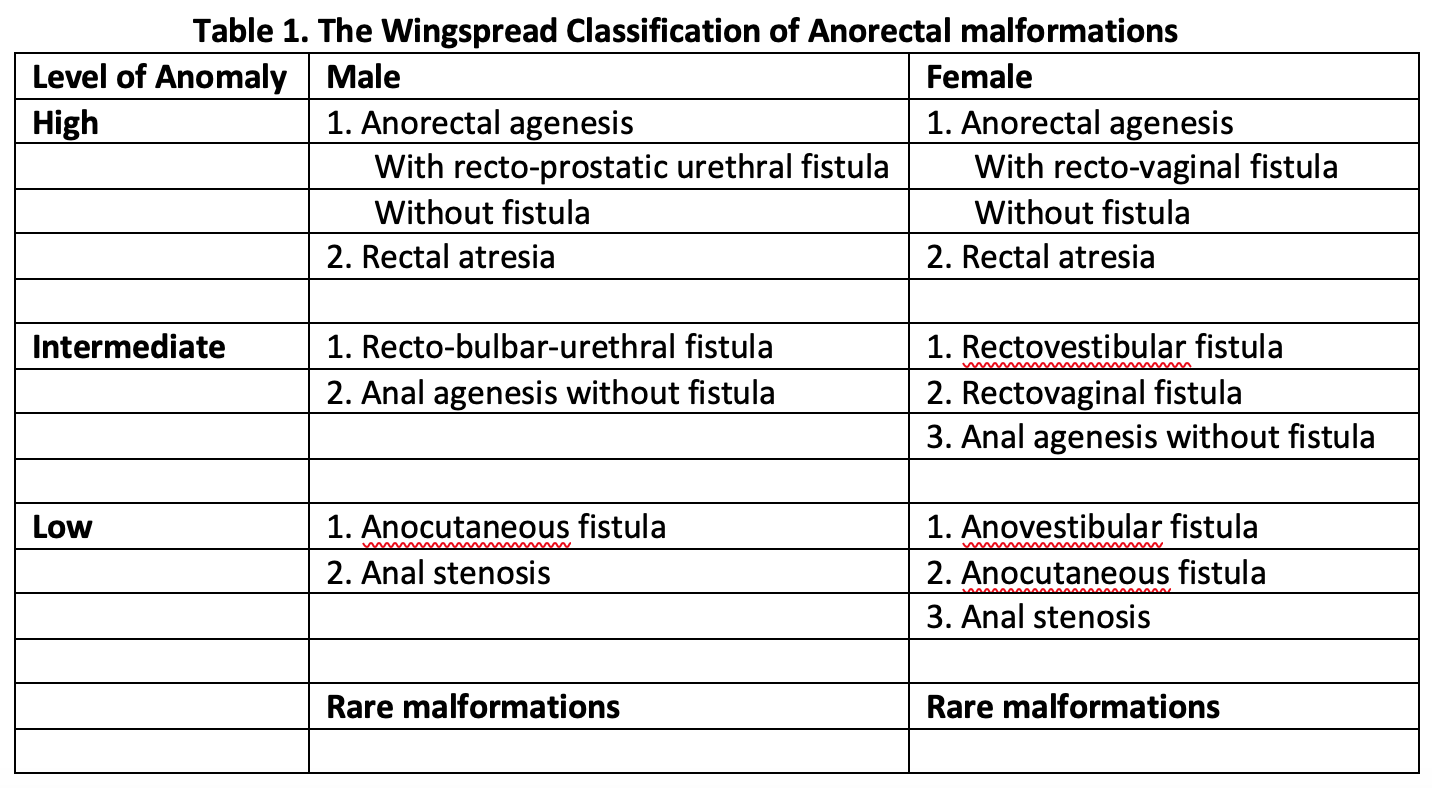

Anorectal malformation is the general term for a variety of diagnoses often referred to as imperforate anus. Patients with this diagnosis do not have a normal anal opening, but instead, a fistulous tract opens onto the perineum anterior to the anal muscle complex or into adjacent anatomical structures. In the male, the fistulous tract can connect to the urinary system and in a female, to the gynecologic structures. The distance the fistulous tract opens from where the proper location of the anal opening usually determines the severity of the defect. The further the fistulous tract opens from the normal anatomic location, the more likely it is that there are additional associated issues such as underdeveloped musculature and anal muscle complex. Correctly classifying the anorectal malformation has significance regarding the patient’s prognosis, and it is a crucial component of determining the patients’ long term potential for bowel control.

Etiology

While a specific cause of anorectal malformations is not known, it is very likely that genetic factors play a role in their development. The incidence of having a second child with an anorectal malformation is approximately one percent.[1] There are several genetic syndromes with an increased incidence of anorectal malformations such as the Currarino triad which exhibits autosomal dominant inheritance, and patients with trisomy 21 have a known association with anorectal malformation without fistula. Approximately 95% of patients with trisomy 21 have anorectal malformation without fistula compared to only 5% of all patients with anorectal malformations.[2] There is also some data to suggest environmental factor exposures may be related to the development of anorectal malformations such as in vitro fertilization, thalidomide exposure, and diabetes.[3] Animal models have also shown exposure to trans-retinoic acid, and ethylene thiourea correlates with anorectal malformations.[3]

Epidemiology

Anorectal malformations occur approximately in 1 in every 5000 live births. They are slightly more common in males (1.2 to 1). The majority of male patients with an anorectal malformation have some form of connection to the urinary system, or a recto-urethral fistula (approximately 70% of this patient population). The most common type of anorectal malformation in female patients is a recto-vestibular fistula.

Pathophysiology

Several theories address the pathophysiology and development of anorectal malformations. One theory is related to the hypothesis that embryonically the urinary tract, reproductive tract, and gastrointestinal tract form a common channel called a cloaca, which is followed by separation of these structures and the migration of the anorectal septum around the seventh week of gestation.[4] This theory hypothesizes that abnormal development of the anorectal septum results in the formation of anorectal malformations. However, there is still ongoing discussion about how the septum forms or if it is even related to the creation of anorectal malformations. A second theory hypothesizes that the rectum migrates towards the perineum during development, and this is abnormal in the formation of anorectal malformations. Neither of these theories has confirmation from embryologic models, and further work is needed to improve our understanding of anorectal malformations and their etiology.[5][6][7]

History and Physical

The majority of patients with anorectal malformations receive their diagnosis as newborns. A full newborn physical exam is vital in these patients as is a thorough work up as approximately 60% of patients will have an associated anomaly.

In addition to a perineal/anal exam, which is mandatory, a full physical newborn examination in a patient with an anorectal malformation includes listening to heart sounds to see if a murmur can be auscultated, examining the limbs for any anatomic abnormality, and a full genitourinary exam.

For an anus to be normal, it should be in the correct location and the proper size, based on age. The normal size anus of a full-term infant is a 10 to 12 Hegar dilator (an instrument used to size the anus), and the size of a 12-month-old should be about a 15 Hegar dilator. The basis of the correct location is on the anal opening being in the center of the anal muscle complex. The position of the anal opening to the muscle complex cannot always be discerned in the clinic and often requires an exam under anesthesia.

The perineum should be thoroughly evaluated taking care to pay attention to features such as the development of the buttocks, the presence of a gluteal fold, and the examination for any type of opening or orifice on the perineum. In female patients with an anorectal malformation, a thorough vaginal exam should also take place, taking care to note the number of openings on the perineum. These physical exam features can help give clues as to the type of anorectal malformation.

Evaluation

Multiple diagnostic studies are necessary for patients diagnosed with an anorectal malformation. While anorectal malformations can occur as an isolated finding, they require additional workup as 60% of patients have an associated anomaly, and there is a correlation of anorectal malformations with the VACTERL defects (vertebral, anorectal, cardiac, tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia, renal, and limb).[2]

Because of the known VACTERL association with anorectal malformations, for every newborn diagnosed with an anorectal malformation on physical exam, the following radiographic studies are necessary. After placement of a nasogastric or orogastric tube, plain abdominal and chest films should be obtained to rule out the presence of esophageal atresia with or without tracheoesophageal fistula. Spine radiographs should also be obtained to rule out vertebral anomalies. In male patients, if the presence of meconium on the perineum without an apparent perineal fistula does not present at 24 hours of life, a lateral prone film, or invertogram, should be obtained. Before obtaining the invertogram, the patient should be positioned prone with the buttocks elevated for at least 15 minutes so that air in the gastrointestinal tract has time to migrate to the most distal rectum; this will aid in the assessment of the most distal level of the bowel and help to determine the need for a colostomy. For female patients with a single perineal orifice and a cloaca diagnosis, an abdominal ultrasound should be obtained to both evaluate for hydrocolpos and hydronephrosis. Additionally, an echocardiogram is in order for all patients with an anorectal malformation to rule out congenital heart issues, and a spinal ultrasound should be obtained to screen for the tethered spinal cord. The sacral ratio should also be calculated from anteroposterior and lateral films as this helps give prognostic information to the families about bowel control for the child as they grow and develop.[2]

Treatment / Management

Perineal fistulas and rectovestibular fistulas:

For patients with perineal fistulas, a repair can be performed in the neonatal period if the surgeon is comfortable with the procedure, and there are no other anomalies that would preclude anesthesia such as a cardiac defect. The clinician can also delay the repair if the fistulous tract is large enough to perform dilations with a Hegar dilator and stool evacuation can be reliable. The same dilation strategy works for a female patient with a rectovestibular fistula as the anatomy can be challenging in the neonatal period, and dilating can allow the child to grow and improve the ease of surgical intervention.

For either patient population, it is crucial to ensure that stool is decompressing well with the dilation management, and the child is not becoming distended. If being managed with dilations, the surgical repair should occur at approximately 3 months of age. This way, the defect can undergo correction before transitioning to solid food, reducing the risk of development of constipation leading to rectal dilation that would impact function.

Surgical repair of these malformations is generally through a posterior sagittal incision, and the abdominal entry is not necessary.

Rectourethral fistulas or Cloaca:

Any male patient with a urinary fistula should undergo diversion in the neonatal period with a diverting descending sigmoid colostomy with a separated mucus fistula. This strategy allows for the child to grow before surgical intervention, and also evacuate stool from the distal limb of the bowel that connects to the urinary system. Furthermore, the mucus fistula allows for a distal colostogram to be performed preoperatively to determine the exact type of rectourethral fistula assisting with preoperative planning and operative strategy for repair.

Patients with a single perineal orifice consistent with a diagnosis of cloaca should also undergo a diverting ostomy and mucous fistula in the neonatal period. These patients also require much more complex preoperative and operative management as well as lifelong care and should be considered for referral to a specialty center.

The timing of the definitive repair of high malformations can depend on the exact type of malformation and other associated anomalies, especially cardiac defects. Typically, surgical repair occurs sometime around or after 3 months of age. Surgical repair can still be performed with a posterior sagittal incision if the rectum and the fistula present on the distal colostogram below the level of the coccyx. Laparoscopy can be a crucial surgical strategy for high malformations such as a recto-bladder neck fistula.

Differential Diagnosis

Although almost all patients without a perineal opening get diagnosed in the newborn period, few patients with anorectal malformation can have a delayed diagnosis. These are most commonly children with perineal fistulas or anal stenosis that may go unrecognized in the neonatal period. In the case of a question of the presence of an anorectal malformation, an exam under anesthesia of the anus should be performed by a pediatric surgeon to assess if the opening is the correct size and the proper anatomic location (centered within the muscle complex.) Occasionally a patient may present with an anal opening that appears to be more anterior than is typical in most patients, which is a normal variant if the anal opening sizes appropriately and is in the center of the muscle complex.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with an anorectal malformation is related to long term potential for bowel control, or the ability to be continent. The three factors that can help predict continence are the type of anorectal malformation, the sacral ratio, and the spinal cord quality. The further the fistula is from the normal anatomic location, the less the chance of continence for the child as they grow older. A low sacral ratio can also be indicative of decreased continence. Spinal issues, such as tethered cord, if present, are also a negative prognostic indicator for continence. However, despite these predictors being present, a child with these prognostic factors can still be clean and socially continent with an appropriate bowel management program and specialty care.

Complications

Complications can occur intraoperatively if care is not taken to stay in the correct tissue plane, which can also lead to misplacement of the anus or placement outside the center of anal muscle complex. Additional intraoperative complications for males can include injury to the urinary structures, including the urethra, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens. In females, the vagina can suffer injury.

Post-operative complications can include superficial and deep wound infection, dehiscence of the anastomosis, prolapse of the anoplasty, or stricture of the anoplasty. Recurrent fistulas between the urinary system in males or gynecologic system in females can also occur. These usually occur if the surgical repair is on excessive tension or there is inadequate blood supply to the rectum. Recurrent fistulas can also occur in the setting of an intraoperative injury to the anterior structures such as the urethra or the vagina. In this setting, care should be taken to ensure the healthy rectal wall as opposed to the repaired structure, and a fat pad should also be placed to buttress the repair.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should primarily focus on helping the parents of a child with anorectal malformation understand the long-term issues that the child will potentially face surrounding continence. The three clinical features, when combined, can assist in predicting the long term potential for continence include the type of anorectal malformation, the sacral ratio, and the quality of the spinal cord. In terms of the type of anorectal malformation, the further the fistula from the normal anatomic location, the lower the likelihood of continence. A normal sacral ratio is 0.9 and a sacral ratio less than 0.4 is a poor predictor of continence. Urinary tract infections also require tracking in patients with anorectal malformations. In female patients, the onset of menstruation is vital to ensure no Mullerian obstruction exists. Finally, the presence of spinal anomaly such as tethered cord also predicts a lower potential for bowel control.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ultimately, these patients benefit from an interprofessional team approach to their care. Specialists, including pediatric general surgery, urology, gynecology, specialty-trained nurses, and gastroenterology are often required to comprehensively treat this patient population successfully and provide the lifelong management they need for success, and social continence; these different disciplines need to work collaboratively to bring about the most optimal treatment and outcomes for these patients. [Level V] Important areas for future research should relate to patient-centered outcomes, especially their quality of life. Additionally, quality metrics among high volume centers may be tracked in the future to set a standard of care for outcomes for this patient population.