Continuing Education Activity

A mastectomy is a surgical procedure involving removal of all or part of the breast. The term originates from the Greek word mastos, meaning woman's breast, and the Latin term ectomia which signifies excision of. Mastectomy classifies into partial, simple, modified-radical, and radical. This activity describes the indications, contraindications, and complications of mastectomy and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the management of patients with breast cancer.

Objectives:

Review the indications of mastectomy.

Describe the technique of mastectomy.

Summarize the complications of mastectomy.

Outline the coordination of education of patients among the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients undergoing mastectomy.

Introduction

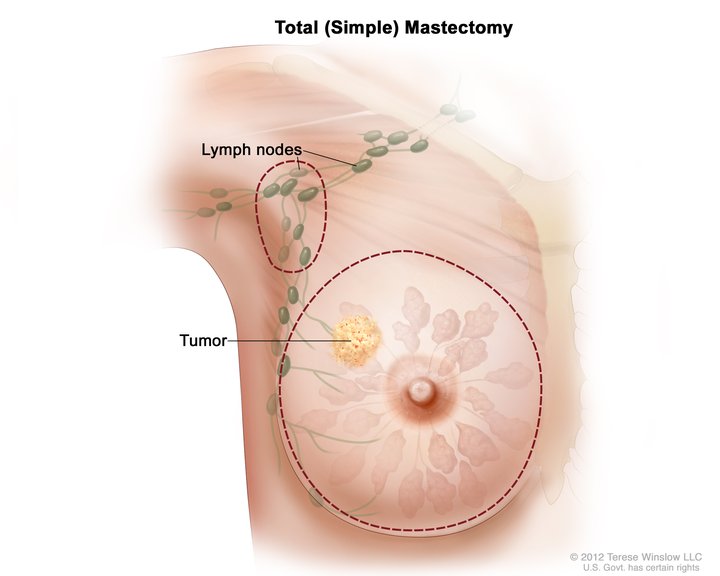

A mastectomy is a surgical procedure involving the removal of all or part of the breast. The term originates from the Greek word mastos, meaning “woman’s breast,” and the Latin term ectomia, which signifies “excision of.” Mastectomy classifies into partial, simple, modified-radical, and radical (see Image. Total Simple Mastectomy). Other variations in terminology or technique include skin-sparing mastectomy and nipple-areolar-sparing mastectomy, which are techniques that often accompany breast reconstruction.

Anatomy and Physiology

The breast is found on the anterior thoracic wall and overlies the pectoralis major muscle. The superior border of the mature female breast approaches the level of the second or third rib and then extends inferiorly to the inframammary crease or fold. The medial boundary of the breast is the sternal border. Laterally, the breast extends to the mid-axillary line. Posteriorly, approximately two-thirds of the breast overlies the pectoralis major muscle, and the remaining portion overlies the serratus anterior and upper portion of the oblique abdominal muscles.[1] The portion of the upper breast that extends superior-laterally toward the axilla is often referred to as the axillary tail of Spence. The breast divides into four quadrants which allow for consistency in the documentation of findings on physical examination or breast imaging. The four quadrants are upper inner, upper outer, lower inner, and lower outer. The majority of breast tissue resides in the upper outer quadrant, including the axillary tail of Spence. As a result, it is the most common location for breast cancer.[2]

The breast is composed of mammary tissue and covered by subcutaneous fat and skin, and possesses superficial and deep fascial layers. The superficial layer of fascia is deep to the dermis and covers the breast anteriorly, and then extends over the medial and lateral breast. The deep layer of superficial fascia covers the posterior surface of the breast and lies anterior to the pectoralis major fascia.[3] Suspensory ligaments of Cooper are fibrous bands of connective tissue that extend from the deep layer of superficial fascia and run through the breast parenchyma and insert perpendicularly to the dermis. It is the weakness of these ligaments that are responsible for breast ptosis.[3] Breast tissue includes epithelial parenchymal elements and stromal tissue. In their text, The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Disease, Bland and Copeland detail the intricate anatomy of the breast. The epithelial component comprises about 10 to 15% of the overall breast volume, and the remainder is composed of stromal elements. The breast stroma is made up of approximately 15 to 20 lobes, and these further subdivide into nearly 20 to 40 lobules. Lobules are made up of branched tubuloalveolar glands. The intervening spaces between the individual lobes contain adipose tissue. Each lobe drains into a major lactiferous duct that extends to the nipple.

Blood supply to the breast comes from several vessels running medially and laterally, as well as several deeper penetrating vessels that must pass through chest wall muscles before reaching the breast. Medially, the internal mammary artery gives rise to various perforating branches. These two to four anterior intercostal perforating arteries pass through the pectoralis major into the breast tissue as medial mammary arteries. Laterally, the arterial supply to the breast comes from the lateral branches of the posterior intercostal arteries and branches of the axillary artery, including the lateral thoracic artery and pectoral branches of the thoracoacromial artery. The lateral vessels wrap around the superior and lateral border of the pectoral muscle to reach the breast.[4]

Venous drainage of drainage typically follows the arterial supply, with most of the drainage extending toward the axilla. Principal venous drainage is through the perforating branches of the internal thoracic vein, tributaries of the axillary vein, and perforating branches of the posterior intercostal veins. Knowledge of venous drainage is essential, as the lymphatic channels typically follow the course of blood vessels. This lymphatic drainage is relevant as it is the pathway for potential cancer metastasis via lymphatic and venous channels.

Breast lymphatic drainage is via the axilla 95% of the time. There is some variation in the description of lymph node groups between anatomists and surgeons. Surgeons typically define axillary nodes with respect to their relationship to the pectoralis minor muscle. Lymph nodes located lateral to or below the lower border of the pectoralis minor muscle are called Level I, and this typically includes the external mammary, axillary vein, and scapular lymph node groups. Level II lymph nodes are located deep to the pectoralis minor muscle and include the central lymph node group and possibly some of the subclavicular nodes. Level III axillary nodes are medial or superior to the upper border of the pectoralis minor muscle and include the subclavicular lymph nodes. Surgeons also commonly identify Rotter’s or interpectoral nodes that are located between the pectoralis major and minor muscles. These Rotter’s nodes may further drain into the central or subclavicular node groups representing a possible “skip pathway” for tumor cells to metastasize from the breast to level III nodes while bypassing levels I or II.[5][6] Other sites of lymphatic drainage include the internal mammary chain, the lateral and medial intramammary regions, the interpectoral region, and the subclavicular lymph node basin.[5]

Indications

The most frequent indication for mastectomy is a malignancy of the breast. In most cases, the mainstay of treatment of breast cancer necessitates localized surgical treatment (either mastectomy or breast-conserving surgery) and can be in combination with neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, including radiation, chemotherapy, or hormone antagonist medications, or a combination thereof. Tumor characteristics like size and location and patient preference are a significant part of the decision-making process, given that in many circumstances, survival rates are equivalent among patients undergoing mastectomy or lumpectomy with adjuvant radiation therapy.[7]

Briefly, cancers of the breast may include both invasive and non-invasive histologies. The most common breast cancer diagnosis is invasive ductal carcinoma, and approximately 85% of all invasive breast cancers are ductal in origin. Alternatively, invasive lobular carcinoma and other infrequently seen histologies, such as breast sarcoma or breast lymphoma, are much less common. Non-invasive carcinoma of the breast includes ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ. The latter is often regarded as a marker of increased risk of future breast cancer and may best be considered a benign precursor lesion.[8]

Patients with Paget’s disease of the breast may be considered for mastectomy as well. Paget’s disease is a rare manifestation of breast cancer where neoplastic cells are present in the epidermis of the nipple-areolar complex. While the disease may remain confined to this area, approximately 80 to 90% of cases will have an associated cancer elsewhere within the involved breast.[9] Total mastectomy with axillary sentinel node biopsy has been the traditional approach to surgical management of Paget’s disease. Central lumpectomy with complete removal of the nipple-areolar complex has been effective for local control in patients without an associated cancer elsewhere in the breast when followed with whole breast radiation therapy.[10]

Mastectomy may be indicated in patients whose disease is multifocal or multicentric within the breast due to the volume and distribution of disease. Also, patients who present with advanced locoregional disease, including large primary tumors (T2 lesions greater than 5 cm) and skin or chest wall involvement, may benefit from mastectomy in many situations. Patients who present with inflammatory breast cancer are also treated with mastectomy, in addition to systemic chemotherapy and radiation treatment, due to tumor burden within the dermal lymphatic channels and more diffuse involvement of the underlying breast parenchyma.

Patients who initially undergo breast-conserving surgery (i.e., lumpectomy or partial mastectomy) and have margin involvement with tumor cells may be considered for a mastectomy if margin re-excision is not successful or is not technically or cosmetically feasible. Clear or negative margins following the resection of a primary tumor are a strong factor in reducing the risk of recurrence.[11] Mastectomy is also indicated in patients with recurrent breast cancer who underwent previous treatment with lumpectomy and radiation.

In patients who do not have a diagnosis of malignancy, mastectomy may be an option for risk reduction or prophylaxis in certain situations. Patients who are proven to carry a deleterious BRCA genetic mutation are at increased risk of breast cancer throughout their lifetime. A BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers have a lifetime risk of breast cancer as high as 80 to 85%.[12] Even in the absence of a diagnosis of breast cancer, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) supports the recommendation of risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy in patients who are BRCA1 or BRCA2, p53, PTEN, or other gene mutation carriers and adds that special high-risk screening protocols exist for this subset of patients.[13] However, routine contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in average-risk patients with unilateral disease does not provide a survival benefit and is often discouraged.[14]

Contraindications

In most situations, mastectomy may be done safely and easily if medically indicated. There are a few crucial factors that merit consideration as contraindications for surgery. These can often be broken down into two separate categories: systemic and locoregional. Mastectomy may be contraindicated in patients with proven distant metastatic disease. Also, frail or elderly patients with significant medical co-morbidities or systemic organ dysfunction may not be candidates for surgery due to the burden of their overall health and poor performance status. Patients who have a predicted high risk of mortality associated with surgery or anesthesia are not candidates for surgery. For patients with advanced locoregional disease, mastectomy may be relatively contraindicated at the time of diagnosis if there is skin or chest wall involvement and concerns regarding the ability to close the surgical wound or obtain a negative surgical margin. In these circumstances, neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy, radiation, or endocrine therapy may be of benefit to reduce the volume or extent of local disease and open the door for surgery.

Equipment

Mastectomy may be performed using sharp dissection with a scalpel or scissor technique. Another alternative is to use an energy device such as electrocautery or one of the various ultrasonic devices for the dissection of the breast from the superficial tissues and to release the posterior attachments from the chest wall. Standard general surgery equipment, including retractors and suction, is often utilized. At the discretion of the surgeon, a temporary, closed suction drain (i.e., Jackson Pratt drain) may be placed in the wound bed to decrease the rate of seroma formation. Absorbable suture is the most common choice for closure of the mastectomy defect and incision.

Axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy is commonly an option for staging purposes at the time of definitive breast surgery. Most surgeons employ a dual tracer technique, which typically involves the use of technetium sulfur colloid, which is injected into the breast preoperatively by the nuclear medicine department of radiology. Intraoperatively many surgeons will inject a vital blue dye, such as methylene blue or isosulfan blue, into the breast to aid in the identification of axillary sentinel lymph nodes. A gamma probe is required to detect any nuclear tracer uptake in the axilla and to guide dissection and exploration in this region for biopsy.

Personnel

Breast cancer care is complex and involves a comprehensive interprofessional care team. A general surgeon or breast/oncologic surgeon typically performs the mastectomy. Additional personnel involved during mastectomy procedures include perioperative nursing staff, anesthesia providers, and surgical technologists or assistants in surgery. For patients who require axillary node biopsy at the time of mastectomy, a radiologist or nuclear medicine technologist is often involved for perioperative technetium sulfur colloid injection as part of sentinel lymph node mapping. In patients undergoing reconstructive procedures, a plastic surgeon typically works alongside the general or breast surgeon to perform the appropriate reconstructive surgery, which has its basis in various patient factors. Additionally, most patients who undergo a mastectomy do so because of malignancy, and their postop care team includes medical oncology and possibly radiation oncology. Following mastectomy, patients may require home healthcare nursing support and even physical or occupational therapy to maximize the return of capacity for activities of daily living.

Preparation

Mastectomy is typically an elective procedure, and patients usually report to the hospital or surgical center on the day of their surgery. Pre-operative antibiotics are indicated for patients undergoing mastectomy, with or without axillary surgery or reconstruction, to reduce the risk of surgical site infection; this consensus statement came from the American Society of Breast Surgeons and was updated in 2017. A first-generation cephalosporin is the antibiotic of choice for prophylaxis unless the patient is allergic or has a history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection.[15]

Patient positioning is in a supine position in the operating room, and the breast, chest wall, axilla, and upper arm are exposed after induction of anesthesia. Many surgeons may include the contralateral breast in the prepped operative field. The field is sterilely prepped with an agent to decrease the presence of skin flora and reduce the risks of surgical site infection. Alcohol-based skin preps, such as chlorhexidine gluconate, are common agents chosen for surgical antisepsis.

Perioperatively, surgeons should prepare patients for their procedure and discuss anticipated postoperative course and care. Many surgeons elect to place a drain at the time of mastectomy to evacuate any fluids that may accumulate in the wound bed and to promote adherence of the flaps to the chest wall. Patients benefit from education on the aspects of drain care and recording an accurate log of output. Patients should also receive counsel regarding their postoperative restrictions regarding lifting, driving, and any other limitations in the immediate recovery period.

Technique or Treatment

While there is a historical reference to surgical removal of the breast dating back to the 18 century, William Halsted described his radical mastectomy technique in 1894, where “suspected tissue should be removed in one piece.”[16] This radical technique involves complete en bloc resection of the breast with the pectoralis major muscle and regional lymphatics. There was a significant amount of skin sacrificed, and a skin graft was often necessary for coverage of the chest wall defect with this approach. This technique left women with significant deformities and disabilities. As a result, there have been several modifications to the technique to reduce the morbidity of the operation. In the 1940s, David Patey modified the Halsted radical mastectomy by preserving the pectoralis muscle, and his outcomes were favorable for less postoperative complications, including pain, lymphedema, and limitations in upper extremity mobility.[17]

John Madden described the current standard for a mastectomy in 1972. This technique involves making an elliptical incision circumscribing the breast and including the nipple areolar complex while keeping the site of the tumor as a central landmark.[18] The mammary tissue is separated from the skin flaps and resected along with the pectoralis major fascia while preserving both pectoral muscles. As a result, this approach requires less disruption of surrounding neurovascular and lymphatic structures. Originally described with this modified radical mastectomy technique, Madden included level I-III axillary lymphadenectomy for staging purposes, and this was thought to offer a therapeutic benefit as well.[17] In contrast to this modified radical mastectomy technique, total mastectomy refers to the surgical removal of all mammary tissue. However, no axillary node dissection is necessary.

As reconstructive techniques have evolved and become more popular, some patients who choose to have breast reconstruction may be candidates for skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomy. Regardless of approach, oncologic principles take precedence over cosmetic concerns. As the name suggests, skin-sparing mastectomy is designed to preserve a healthy skin envelope for immediate breast reconstruction, provided adequate margins can be achieved. Nipple-sparing mastectomy allows the removal of the mammary tissue and pectoral fascia while preserving the nipple-areolar complex and the entire skin envelope of the breast. This surgical approach is done only in patients undergoing immediate breast reconstruction. With this approach, it is critical to preserve blood supply to the nipple areolar complex to prevent flap ischemia or breakdown.

With all described mastectomy techniques, uniform flaps are created by dissecting just above the superficial layer of the superficial fascia of the breast. There has been much controversy over the ideal flap thickness, with the ultimate goal of removing all possible breast tissue while preserving skin viability.[19] As noted above, mastectomy dissection should continue to the anatomic boundaries of the breast, regardless of the type or location of skin incision used. Flaps are elevated and retracted at a right angle to the chest wall while the surgeon retracts the breast tissue away from the overlying tissue. The skin flap is elevated to the level of the clavicle superiorly, the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi laterally, the sternal border medially, and to just below the inframammary crease inferiorly. Once the dissection of the overlying flaps is complete, the breast is removed, working from the superomedial border to the inferolateral border. A closed suction drain is usually placed beneath the skin flaps in the wound bed, and the incision is closed in a two-layer fashion using absorbable suture.

Complications

Patients tolerate mastectomy well in most settings with low morbidity and mortality. However, several possible complications may occur. These include seroma or hematoma formation, wound infection, skin flap breakdown or necrosis, and lymphedema. Seroma is a collection of fluid in a surgically created cavity that results from the transection of vessels and lymphatics. Most surgeons used closed suction drains beneath the skin flaps to decrease the rate of seroma formation. The frequency of surgical site infection in patients undergoing breast surgery is approximately 8%.[15] The most common organisms involved are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus epidermis, and infections should receive treatment with an appropriate antibiotic, with or without opening of the wound. Similarly, flap necrosis occurs in about 8% of patients and is related to inadequate blood supply to the flap, wound closure under tension, obesity, and type of incision (vertical versus transverse). Necrosis is managed with debridement and skin graft coverage if indicated. Lymphedema is less commonly present since the advent of modified mastectomy techniques. Axillary lymph node dissection is the most significant risk factor for the development of lymphedema, with a reported incidence of greater than 20%. Comparatively, 3.5 to 11% of patients who have sentinel lymph node biopsy develop lymphedema.[20] In patients who develop lymphedema, early intervention with physical therapy and decompressive massage techniques can help prevent progression and, in some cases, reduce lymphedema.

Clinical Significance

There have been significant advances in the patient management of breast cancer patients since Halsted first described his radical surgery in the late 1800s. There has been a growing trend toward breast conservation, and numerous studies have looked at the efficacy of breast-conserving surgery when compared to standard mastectomy techniques. With the addition of adjuvant therapies, including radiation and systemic treatment with chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, rates of mastectomy have declined. Twenty-year follow up data from NSABP-06 shows no difference in disease-free survival or overall survival in patients randomized between modified radical mastectomy, lumpectomy with axillary dissection, and radiation or lumpectomy and axillary dissection alone.[7][21] NSABP-06 was critical in establishing the concept of breast-conserving surgery, and the results have received validation from other clinical trial groups, including the European Milan Cancer Institute.[21]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Numerous clinical trials have evaluated the various aspects of surgical care of breast cancer patients. Leading the way, the NSABP has published initial outcomes and delayed follow up data that has shown no decrease in disease-free survival or overall survival in patients undergoing modified mastectomy, as compared to the original more radical techniques. Many national and international leaders and researchers, including the American Society of Breast Surgeons, continue to work toward improving surgical quality and outcomes for patients with breast cancer.