Continuing Education Activity

The diagnosis and management of cholangiocarcinoma are challenging and complex. To achieve good results and provide appropriate patient care, the treatment options, contraindications, goals, and possible outcomes must be well defined. This article outlines the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of cholangiocarcinomas, and reviews the types and subtypes of the cholangiocarcinoma. Furthermore, it describes various surgical, interventional, and radiation therapy options available. It also highlights the importance of the interprofessional team in managing patients suffering from cholangiocarcinoma.

Objectives:

Review pathology of cholangiocarcinoma.

Describe anatomical and morphological classifications of cholangiocarcinoma and surgical Bismuth-Corlette classification of perihilar cholangiocarcinomas.

Outline typical imaging features of intrahepatic, perihilar, and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Explain the role of interprofessional care of cholangiocarcinoma patients which includes surgery, medical oncology, interventional radiology, and radiation oncology teams.

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is a rare malignancy of the epithelial cells from various areas of the biliary tree, including intrahepatic, perihilar, and extrahepatic bile ducts. Histopathologically they are predominantly adenocarcinomas (95% of cases). Cholangiocarcinomas are highly lethal because most cases are locally advanced at the time of presentation. About 50% of cases are perihilar, 40% are distal, and 10% are intrahepatic.[1]

[Gopal, you'll probably talk about all 3 subheadings in paragraph form in intro, but I'll add them and you can remove in any given section. We can also take out the roman numerals at copy, but I think they'll help you find each heading better. JB]

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Etiology

Many cases of cholangiocarcinoma arise de novo and do not have a specific risk factor, but there are a number of risk factors that have been identified, including primary hepatobiliary disease, genetic disorders, toxic exposures, and infections. Primary hepatobiliary disorders include primary sclerosing cholangitis, fibropolycystic liver disease, cholelithiasis/cholecystitis, and chronic liver disease. Primary sclerosing cholangitis has a strong association with cholangiocarcinoma, with nearly 30% of cholangiocarcinomas being diagnosed in patients with this disease.[2]

Genetic disorders include Lynch syndrome, BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome, multiple biliary papillomatosis, and cystic fibrosis. The only clear association between toxins and cholangiocarcinoma is Thorotrast, which is a radiocontrast that has been banned. No clear association has been made between smoking/alcohol use with cholangiocarcinoma. Infections that have been linked with cholangiocarcinoma are liver flukes (clonorchiasis and opisthorchiasis), HIV, and Helicobacter pylori. Finally, patients suffering from diabetes mellitus, obesity, and metabolic syndrome have an increased risk as well.[3]

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Epidemiology

Cholangiocarcinomas comprise about 3% of gastrointestinal malignancies and are the second most common primary liver tumors and account for approximately 10-15% of all hepatobiliary malignancies.[4] The incidence of intrahepatic lesions has been rising, while the incidence of extrahepatic lesions has been falling in recent years. As with many cancers, the incidence increases with age, with the most common age group being 50 to 70. Men are slightly more likely to be diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma than women, likely due to primary sclerosing cholangitis being more common in men.[5][6]

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Pathophysiology

Similar to many malignancies, cholangiocarcinoma arises from precursor lesions such as the more common biliary intraepithelial neoplasia and the less common intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Normal epithelium becomes one of these premalignant lesions through mutations in a variety of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. While the specific molecular pathway has not been identified, cholangiocarcinomas harbor mutations in genes such as RAS, BRAF, p52, SMAD4, and more.[7][8][9][10]

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Histopathology

Cholangiocarcinoma arises from bile duct epithelium, anywhere along the intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile ducts.[11] Most of the cholangiocarcinomas are adenocarcinomas (90-95%), while the remaining are mostly squamous cell carcinomas. They are further subtyped into sclerosing, nodular, and papillary depending on morphology. Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma is an indeterminate type between cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma but are staged as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas rather than hepatocellular carcinomas.[12]

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

History and Physical

The history and physical examination findings can be vague in cholangiocarcinomas. The presentation depends on the location of the tumor. Generalized symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma can include abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, fatigue, and night sweats.[13] Extrahepatic tumors become symptomatic earlier because the tumor obstructs the biliary system leading to jaundice, pruritus, clay-colored stools, and dark-colored urine. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are usually asymptomatic until they become very large, and they can present with nonspecific symptoms related to mass effect or hepatic parenchymal invasion. They are less likely to present with jaundice. In advanced disease, there can be a palpable mass, and/or ascites. Uncommonly, patients can present because of signs related to metastatic disease or metastatic disease in imaging studies.[14]

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Evaluation

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

The choice of diagnostic testing and its results depend on where the lesion is suspected to be, either extrahepatic, perihilar, or intrahepatic. Since the presentation can be nonspecific, it is important to keep cholangiocarcinoma in the list of differentials in patients with signs of biliary obstruction and/or primary sclerosing cholangitis. It may be found incidentally on abdominal imaging as well.

Basic laboratory testing should comprise of liver biochemical tests, including aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and total/indirect/direct bilirubin. In extrahepatic tumors, direct bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase will be elevated, but later in the course due to obstruction, transaminase levels will increase as well. Intrahepatic tumors have more subtle lab abnormalities, including abnormal levels of alkaline phosphatase but usually normal levels of bilirubin. The tumor markers that should be included are carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen, and alpha-fetoprotein. CA 19-9 is usually elevated in cholangiocarcinomas, while AFP is normal.

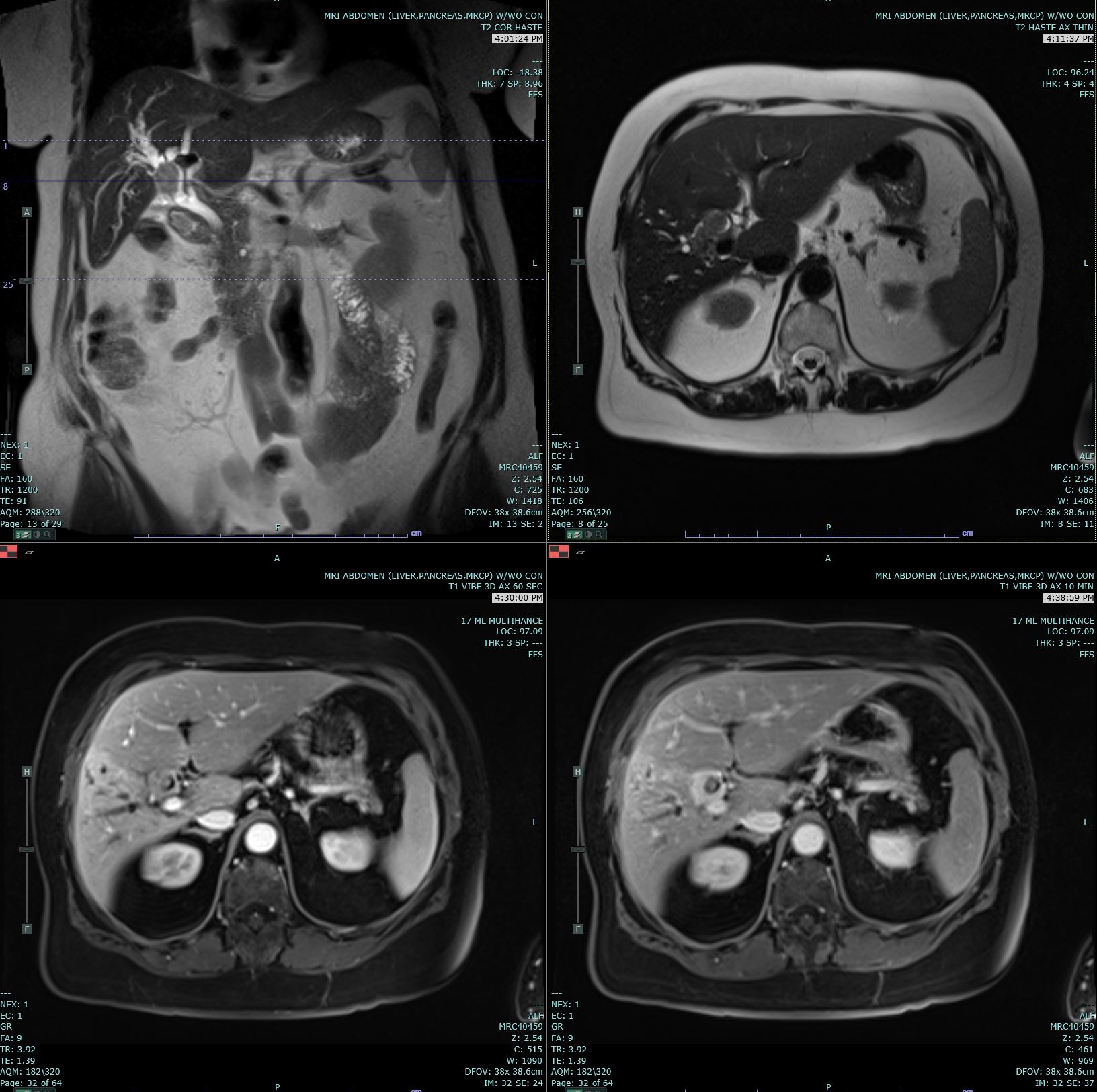

Since jaundice is a common presentation, most patients will reflexively get a transabdominal ultrasound. It will assist in confirming biliary duct dilation, localizing the site of obstruction, and excluding gallstones, although further imaging is important if cholangiocarcinoma is suspected.[15] In perihilar or intrahepatic tumors, further imaging can include magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or a multiphasic contrast-enhanced multidetector-row computed tomography. These tests can help in identifying the location of the tumor, eliminating benign tumors from the differential, and identifying any metastases. In distal extrahepatic tumors, the next step includes EUS or ERCP to visualize the lesion, obtain biopsies (via fine needle aspiration or brush cytology), and relieve obstruction via stents, if any. If the tumor remains in doubt, then a positron emission tomography scan may be beneficial.

CT features may be slightly different based on the type of cholangiocarcinoma:

- Intrahepatic-peripheral CCs usually present as a mass with irregular margins with or without hepatic capsule retraction, and dilatation of the peripheral intrahepatic ducts. On spiral CT, peripheral cholangiocarcinoma usually demonstrates thin, incomplete rim enhancement during both the arterial and portal venous phases.

- Intrahepatic-intraductal CCs can cause dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts with or without an intraductal polypoid mass, lobar atrophy-hypertrophy complex. It can present as irregular masses with markedly low attenuation, minimal peripheral enhancement, and focal dilatation of intrahepatic ducts around the tumor.

- Intrahepatic-perihilar (Klatskin) CCs can cause nonunion of the right hepatic duct and left hepatic duct with or without an intraductal polypoid mass or obliteration of the lumen.

- Extrahepatic CCs present as wall thickening of the extrahepatic duct, mass at the porta hepatis, or with proximal biliary dilatation in the periampullary region.

Tissue diagnosis can be difficult, depending on the location of the lesion, especially in perihilar lesions. Modalities include brush cytology, fine needle aspiration, or CT-guided biopsy. Tissue diagnosis is not needed in patients who are inoperable with classic findings of malignant biliary obstruction or when palliative care is the only option. However, tissue diagnosis is important when there is no clear origin of strictures (patients with PSC), when surgeons or patients need a clear diagnosis before further management, or when nonsurgical management options are chosen.[16]

The staging of cholangiocarcinoma depends on the location of the tumor. There is the Bismuth-Corlette classification for perihilar tumors.[17] The American Joint Committee on Cancer created three different TNM staging systems depending on the location (perihilar, extrahepatic, or intrahepatic). T is for local tumor invasion and is different for each type of cholangiocarcinoma, N is for regional nodal involvement, and M is for the presence of distant metastasis.

Bismuth Corlette classification for perihilar tumors:

- Tumors below the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts (Type 1)

- Tumors reaching the confluence, caudate branches are often involved (Type 2)

- Tumors obstructing the common hepatic duct and either the right or left hepatic duct (Types 3a and 3b, respectively)

- Tumors that are multicentric, or involve the confluence and both the right or left hepatic duct (Type IV)[18][19][18]

Treatment / Management

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

There are medical and surgical treatment options for cholangiocarcinoma, but surgery is the only curative therapy. The effectiveness of corrective surgery depends on the tumor site, the extent of bile duct involvement, nodal involvement, metastatic involvement, and the relationship of the tumor to critical vasculature in the vicinity. Typically, extrahepatic tumors have the best surgical outcomes. However, recurrence is widespread even with complete resection.[20]

In patients with advanced disease, the purpose of treatment is to achieve adequate palliation through biliary stent placement, photodynamic therapy, transarterial chemoembolization, and radiofrequency ablation in selected cases of mass-forming lesions. Also, biliary bypass surgery is considered for palliation in patients in whom stent placement fails or is not possible. Liver transplantation can increase survival time in selected patients.[21]

Surgical techniques for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma are improved by extended resection, portal vein embolization, and associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy. Criteria for resectability is defined by the following features; the absence of retropancreatic and paraceliac nodal metastases or distant liver metastases, the absence of invasion of the portal vein or main hepatic artery (some centers support en bloc resection with vascular reconstruction in such cases), the absence of extrahepatic adjacent organ invasion and lack of disseminated disease.[22]

In patients eligible for surgical resection, challenges are to achieve negative bile duct margins, adequate liver remnant function, and adequate portal and arterial inflow to the liver remnant. Resection with a microscopically negative margin is the only way to cure patients with perihilar-hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Today, resection of the caudate lobe and part of segment 4, combined with a right or left hepatectomy, bile duct resection, lymphadenectomy of the hepatic hilum, and sometimes vascular resection, is the standard surgical procedure for most of the perihilar/hilar cholangiocarcinomas.[23]

The type of surgery is based on the anatomical subtype and the tumor's location. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is usually treated by hepatic resection to achieve negative resection margins. For intrahepatic-peripheral tumors, resection of the involved hepatic segment or lobe is the preferred method. For intrahepatic-intraductal tumors, hepatic lobectomy or segmentectomy with excision of the involved hepatic duct is usually performed. Surgical treatment of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma depends upon the Bismuth-Corlette classification. For type 1 and 2 lesions, the procedure is en bloc resection of the extrahepatic bile ducts and gallbladder with 5 to 10 mm bile duct margins and a regional lymphadenectomy with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction. Type 3 tumors usually also require hepatic lobectomy or trisectionectomy. For Type 3 and type 4 tumors, aggressive techniques such as multiple hepatic segment resection with portal vein resection (hilar en bloc resection) to achieve negative margins should not be a contraindication to resection. For the extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas, pancreatoduodenectomy or a pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure are usually performed.[24]

For curative resection in the management of cholangiocarcinoma, the location and local extension of the tumor dictates the required surgical planning. Accordingly, for the management of Bismuth-Corlette type IIIa tumors, right hepatic lobectomy, with or without resection of the adjacent caudate lobe, is part of the surgical plan. The alternative terminology is hemi-hepatectomy or extended hemi-hepatectomy plus hepatic caudate lobectomy. The index applied to illustrate the longitudinal extent of required resection is the imaginary line between U and P points. The former one relates to the posterior portal sagittal part, and the latter one refers to the right posterior portal branch.[25]

Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation have not been documented to be beneficial in the management. However, neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by adequate surgical resection is recommended to manage perihilar tumors. Some specific anatomic points should be considered while managing the Bismuth-Corlette type III a and b. The right hepatic duct bifurcates earlier than the left. Therefore, tumoral involvement up to the second-order branches is more predictable in type IIIa than in type IIIb. Therefore, type IIIa might be adequately resected with the segmentectomy of segments I and IVb. The exact amount of resection is controversial. That said, if other margins of the tumor are clear in the frozen section assessment, the presence of severe dysplasia or carcinoma in situ would classify the resection as R0.[26]

The other important point is the biliary duct reconstruction following the resection. Accordingly, if the hepatic duct openings in the cutting surface are close, Roux-en-Y anastomosis to the remaining lobe, which in type IIIa would be the left lobe, is recommended. However, if the hepatic duct stumps are far from each other, multi-port anastomosis is recommended.[27]

Differential Diagnosis

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Since the signs and symptoms including jaundice, abdominal pain, and fatigue are very nonspecific the differential diagnosis can be vast. Some possible differential diagnoses include:

- Choledocholithiasis

- Pancreatic cancer

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Hepatocellular carcinoma

- Cholangitis

- Cholecystitis

Radiation Oncology

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Radiotherapy can be used as adjuvant therapy for cholangiocarcinoma following surgery, although its use is controversial. Instead, a combination of chemoradiotherapy is typically administered, improving survival. Many retrospectives and small randomized trials have shown superior outcomes with adjuvant therapy with both chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy is more critical in palliative care, providing improvement of symptoms and may improve survival in locally advanced patients. Concurrently administered chemotherapy may further enhance these results. Newer radiation therapy techniques, including intraluminal transcatheter brachytherapy, intraoperative radiation therapy, intensity-modulated radiation therapy, and three-dimensional treatment planning, permit radiation dose escalation without significant increases in normal tissue toxicity, thereby increasing the effective radiation dose.[28]

External beam radiotherapy has been the most commonly used modality and is typically administered to a total dose of 45–60 Gy. The optimal radiation dose and schedule in the adjuvant and "definitive" treatment of biliary malignancies is unknown. Palliative radiation therapy has frequently been employed in the management of patients with locally advanced and unresectable tumors. Palliative irradiation after biliary bypass prolongs survival in many studies. Adjuvant radiotherapy following resection had a survival benefit in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients with regional lymph node metastasis. The majority of patients with locally advanced, unresectable cholangiocarcinoma die of tumor-related liver failure. Controlling these tumors with ablative radiation will prolong the survival of patients.[29][30]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Treatment Planning

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Medical Oncology

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

There are various factors that influence the effect of chemotherapy and complicate the evaluation, such as control of cholangitis, liver function, and performance status, besides tumor-related factors. Essential drugs currently available are gemcitabine, fluoropyrimidines, and platinum-based therapy.

Most patients with biliary tract cancer develop local recurrence and metastases, and treatment of these patients is, therefore, an important issue. Up to 50% of patients have positive nodes at the diagnosis. Portocaval and porta hepatis are the most common sites. Up to 20% of patients have peritoneal involvement at diagnosis. This may appear as a peritoneal thickening and enhancing nodules. Pulmonary and hepatic metastasis is less common but can occur.

At the time of diagnosis, over two-thirds of patients with biliary tract cancer have an inoperable disease. The chemotherapy regimen of gemcitabine and cisplatin is often used for the inoperable disease. Data from several studies suggest that single-agent gemcitabine or gemcitabine combined with cisplatin or oxaliplatin represents an active and well-tolerated regimen. Targeted therapies to inhibit EGFR, VEGF, MEK, and others are broadly tested in cholangiocarcinoma. In clinical practice, many patients receive second-line chemotherapy after the failure of gemcitabine/cisplatin, although there is no evidence to support second-line chemotherapy so far. Targeted therapy options with RAF kinase inhibitors are also considered for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas with BRAF V600E mutations.[31][32][33]

Staging

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Prognosis

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Surgery is the preferred treatment for all subtypes, but the involvement of the vascular structures and lymph nodes needs to be considered. Although surgery and curative liver transplantation are options for selected patients with perihilar carcinoma, 5-year survival rates are 5 to 10% (the best outcome is with transplant and neoadjuvant therapy). Intrahepatic-peripheral cholangiocarcinomas usually have a relatively indolent course and can be treated with surgery +/- radiotherapy.

Patients with cholangiocarcinoma require individualized management. For patients requiring hepatic resection who have a predicted future liver remnant volume that is inadequate, we suggest portal vein embolization (PVE) to induce lobar hypertrophy prior to resection.

Complications

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Complications can occur from the tumor-like cholangitis, from the surgery, and from chemoradiotherapy. Following complete surgical resection, the most common relapse pattern is local. Among patients who undergo potentially curative resection for cholangiocarcinoma, long-term outcomes vary according to location and stage of the primary lesion, extent of surgery, associated comorbidities, and treatment-related complications.[34]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Consultations

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

Role of interventional radiology:

Radiofrequency ablation has low effectiveness in the cases of cholangiocarcinoma, where the lesions are larger than 5 cm. Recurrence rates for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma are also quite high after radiofrequency ablation.[35] Pre-operative portal vein embolization is used for selective hypertrophy of remnant liver tissue. The principle of portal vein embolization is to redirect portal venous flow to the intended nondiseased future liver remnant, inducing selective hypertrophy and improving the patient’s reserve before surgery. Studies show that, in a patient with otherwise normal liver parenchyma, 25% of the total liver volume should be preserved to minimize the morbidity of surgical resection (40% in patients with chronic liver disease). The safety and efficacy of selective intra-arterial radiotherapy with radioactive 90Y in an adjuvant setting were recently reported.[36]

Deterrence and Patient Education

I. Biliary Premalignant Lesions

II. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

III. Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma

There is no approved screening guideline for cholangiocarcinoma unless a patient has a high-risk condition like primary sclerosing cholangitis, where they should have surveillance imaging done every 6 to 12 months. Otherwise, patients should just maintain routine visits with their providers and be aware of symptoms such as jaundice, abdominal pain, and weight loss.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with cholangiocarcinoma require individualized management. Cholangiocarcinoma has a grave prognosis with high morbidity and mortality. Imaging plays a crucial role in diagnosis and management. Specific features on CT and MRI can result in a confident diagnosis and aid with determining resectability, which can improve prognosis and prevent unnecessary surgery. Among patients who undergo potentially curative resection for cholangiocarcinoma, long-term outcomes vary according to location and stage of the primary lesion, extent of surgery, associated comorbidities, and treatment-related complications. Following complete surgical resection, the most common relapse pattern is local. An interprofessional team that provides a holistic and integrated approach to postoperative care can help achieve the best possible outcomes.