Continuing Education Activity

The diaphragm is a vital organ for mammals as it is the primary muscle for respiration. Diaphragmatic paralysis is the loss of its muscular power and can arise from either weakness of the muscle itself or damage to its nerve supply. Depending on the severity of the paralysis and whether it is unilateral or bilateral, patients can have varied clinical manifestations. A patient may be asymptomatic, while another may be ventilator dependent. This activity explains how to properly evaluate for diaphragm disorders, and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Review the causes of diaphragm disorders.

- Describe the evaluation of a patient with diaphragmatic paralysis.

- Summarize the treatment of diaphragm disorders.

- Outline the importance of enhancing care coordination among the interprofessional team to ensure proper evaluation and management of diaphragm disorders.

Introduction

The diaphragm is a vital organ for mammals as it is the primary muscle for respiration. Diaphragmatic paralysis is the loss of its muscular power and can arise from either weakness of the muscle itself or damage to its nerve supply. Depending on the severity of the paralysis and whether it is unilateral or bilateral, patients can have varied clinical manifestations. A patient may be asymptomatic, while another may be ventilator dependent.

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped musculo-fibrous structure located between the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It constitutes the floor of the thorax and the roof of the abdomen. The word “diaphragm” is derived from the Greek words “dia,” meaning in between, and “phragma,” meaning fence. Although a clear anatomical distinction is not evident, the diaphragm functions as two, separate units (right and left), each with different vascular and nerve supplies. The peripheral portion of the diaphragm is muscular and is composed of three distinct muscle groups. The sternal group originates from the xiphoid process, the costal group originates from the inner surface of the lower six ribs, and the lumbar group originates from two crura and arcuate ligaments which are, in turn, attached to the lumbar vertebra. The central part is made of strong aponeurotic tendinous ligaments without any bony attachment. It is C-shaped and has right lateral, middle, and left lateral leaflets. The anterior sternal attachment of diaphragm is located more cranially compared to posterior lumbar attachment. During inhalation, the muscular part of the diaphragm contracts making it flatter and expands the thoracic cavity outward and downward. This creates negative intrathoracic pressure leading to passive movement of air from atmosphere to the respiratory system along the pressure gradient. When the diaphragm relaxes, the thoracic cavity constricts decreasing the subatmospheric pressure and leading to passive egress of air from the respiratory system during expiration.

Although external intercostal muscles aid in inspiration, the diaphragm is the primary muscle of respiration, and its weakness can impede the respiratory functions. Paralysis on both sides of the hemidiaphragm will cause significant respiratory failure, but paresis of one hemidiaphragm can be asymptomatic due to compensatory function from the other half of diaphragm and recruitment from external intercostal muscles. Voluntary contraction of the diaphragm will also increase the intraabdominal pressure and aid in other vital functions like vomiting, urination, and defecation. It also prevents regurgitation by creating pressure at the lower esophageal sphincter.

The diaphragm has several openings allowing the structures to pass from the thorax to the abdomen. At the level of the eight thoracic vertebrae on the right hemidiaphragm, there is a large opening through which the inferior vena cava enters thorax from the abdomen to join the right atrium. At the level of the ten thoracic vertebrae, there is a posterior midline opening between the two crus of the diaphragm called aortic hiatus through which the descending thoracic aorta enters the abdomen from the thorax, the thoracic duct enters the thorax from the abdomen, and the azygous vein enters the thorax from the abdomen. Between the fibers of the right crus of the diaphragm, there is the esophageal hiatus through which the esophagus locates from the thorax to the abdomen.

The diaphragm functions primarily involuntarily with additional voluntary control when needed. It is innervated by two phrenic nerves originating from cervical nerve roots C3 to C6. Right and left phrenic nerves to innervate the respective hemidiaphragm and control both sensory and motor functions. The right phrenic nerve is located lateral to the caval hiatus, and the left phrenic nerve is located lateral to the pericardium. Each phrenic nerve divides into four trunks, the sternal, anterolateral, posterolateral and crural trunks. The main vascular supply for the diaphragm comes from the bilateral phrenic arteries, which are direct branches of the thoracic aorta.The diaphragm is also supplied by tributaries from the internal mammary arteries, and from pericardiophrenic arteries. Venous drainage occurs through phrenic veins, which drain into the inferior vena cava.

Etiology

Diaphragmatic palsy or paresis can be a result of either direct diaphragmatic muscle weakness and atrophy or damage to the phrenic nerves. Unilateral weakness of one of the hemidiaphragm is more common than bilateral weakness. Depending on the cause, the weakness can be either temporary or permanent.[1][2][3] The cause of diaphragmatic weakness can be divided into the following categories:

Traumatic

This is the most common cause of diaphragmatic weakness. Surgery or trauma can cause injury to the phrenic nerve, leading to diaphragmatic weakness. Cardiac bypass surgery is the most common procedure that causes trauma, with up to 20% risk of diaphragmatic weakness. During the cold cardioplegia for bypass, the phrenic nerve gets phrenic frostbite, leading to temporary loss of diaphragmatic functions. Due to the long course of the left diaphragm in the thorax, left-side diaphragmatic weakness is more common. Any mediastinal procedures, esophageal surgeries or lung transplantation carry a risk of diaphragmatic weakness. Penetrating or gunshot injuries to the thorax can also result in phrenic nerve damage.[4]

Compression

Any space-occupying lesion in the thorax, for example, a mediastinal tumor or lung cancer close to the phrenic nerve, can cause physical compression of the nerve leading to loss of function. Phrenic nerve involvement is seen in 5% of lung cancer. Other causes of compressive damage include an aortic aneurysm, substernal goiter, and cervical spondylosis.

Neuropathic

Phrenic nerve damage cane by caused by many neurological issues like diabetic neuropathy, inclusion body myositis, dermatomyositis, multiple sclerosis, anterior horn cell disease, chronic demyelinating disease, and neuralgic myopathy.[5]

Inflammatory

Many systemic diseases can lead to inflammation of the phrenic nerve or diaphragm leading to diaphragmatic palsy. Viral infections like HIV, West Nile virus and poliomyelitis virus, bacterial infections like Lyme disease, and noninfectious causes like sarcoidosis and amyloidosis have been linked to diaphragmatic weakness.

Idiopathic

In nearly 20% cases, no obvious cause if detected after extensive investigations and are referred as idiopathic.

Epidemiology

Diapahamtic palsy is seen in around 20% cases following cardiac surgery.

History and Physical

Symptoms of diaphragmatic weakness vary depending on the cause and duration. Most patients with unilateral diaphragmatic weakness are asymptomatic and are detected incidentally. One-third of patients report exertional breathlessness. Patients with coexisting debilitating cardiopulmonary conditions can have dyspnea at rest. Most patients with unilateral diaphragmatic weakness show some limitation of exercise capacity and have lower resting oxygen saturation levels. Most patients with bilateral weakness complain of varying degrees of dyspnea from mild exertional breathlessness to dyspnea at rest. As the diaphragm function becomes further compromised during supine position, patients report orthopnea. Progressive hypoventilation can lead to hypercapnia and right heart failure. The hypoxemia and hypercapnia are worse during sleep.

Evaluation

Evaluation usually includes chest radiographs and more advanced imaging. Other tests include pulmonary function tests and electrophysiologic studies.[6]

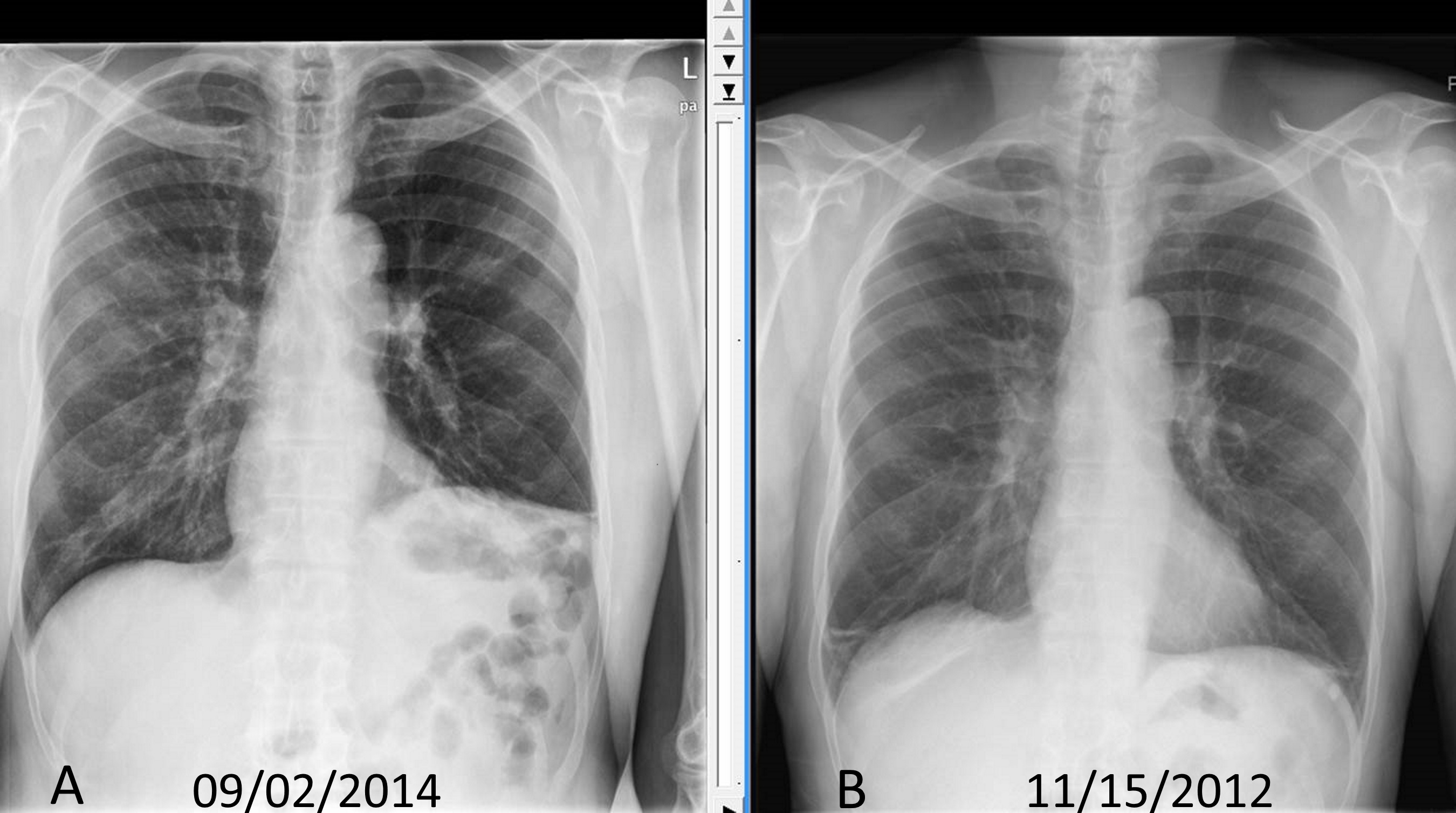

- Chest radiographs: As the diaphragm is positioned obliquely, the dome of the right diaphragm is at the level of the five rib anteriorly and the level of the ten rib posteriorly. Normally the right hemidiaphragm is located at a slightly higher level compared to left hemidiaphragm by around one intercostal space. If one side of the diaphragm is weak, then the normal negative intrathoracic pressure will suck the diaphragm cranially into the thoracic cavity. So, the paralyzed diaphragm will be at a higher level. If the right side is paralyzed, the distance between the right and left diaphragm will be more than two intercostal space, and if the left side is paralyzed, both the hemidiaphragms will appear on the same level. Up to 90% of unilateral diaphragmatic palsy can be diagnosed based on chest x-ray alone. In bilateral weakness, both hemidiaphragms will at a higher level and might be missed on a routine chest radiograms. As the diaphragms are curved, the costophrenic and craniovertebral angle will be acuter. An upward located diaphragm can also cause secondary atelectasis of the lower sub-segments of the lung.

- Fluoroscopic test: All patients with suspected diaphragmatic weakness should undergo a fluoroscopic test to diagnose the functional weakness. On tidal breathing in normal individuals, diaphragmatic contraction will lead to the descent of both hemidiaphragms by at least one intercostal space. On deep breathing or sniffing, the descent of hemidiaphragm is more rapid and more distal. In case of a unilateral weakening of the hemidiaphragm, the diaphragmatic excursion will be reduced or absent. Sometimes, it can show a paradoxical movement of the diaphragm where the diaphragm moves into thoracic cavity during inspiration while the other normal working diaphragm moves downward toward the abdominal cavity. The intercostal muscles and the normal hemidiaphragm will generate negative intrathoracic pressure and suck the paralyzed diaphragm to the thorax. In bilateral weakness, the diaphragm either does not move or moves paradoxically, depending on the severity of weakness.

- Ultrasound of thorax: Ultrasound examination for the thoracic disease is gaining popularity. The diaphragm appears as a thick echogenic line in B mode. In M mode, a paralyzed hemidiaphragm will show no cranial movements of paradoxical caudal movements, similar to a sniff test.

- CT chest: CT of the chest should be done in all patients with diaphragm weakness to rule out any thoracic etiology. Unfortunately, diaphragmatic weakness is not recognized easily and cannot be detected in static CT images.

- Pulmonary function tests: As the diaphragm accounts for 80% of the muscular power of respiration, its weakness will lead to measure by pulmonary functions tests. Forced vital capacity will decline by 50% predicted in unilateral diaphragmatic weakness and up to 75% in bilateral weakness. Normally, the lung functions decline less than 15% in supine position due to the restriction of thoracic expansion and positive pressure from abdominal structures. In diaphragmatic weakness, this accentuates and on repeating the spirometry in supine position forced vital capacity will further decrease by 15% to 20% in unilateral weakness, and 20% to 30% in bilateral weakness. Maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressure will also be reduced. Total lung capacity, functional residual capacity, residual volume, and diffusion factor remain unchanged in unilateral weakness but can be reduced in bilateral weakness.

- Electrophysiological tests: In diaphragmatic electromyography, the phrenic nerve is stimulated electrically, and the mechanical response of the diaphragm is detected along with trans-diaphragmatic pressure. In phrenic nerve pathology, there is prolonged latency and reduced trans-diaphragmatic pressure. However, in primary diaphragmatic pathology, the phrenic nerve conduction is normal, but compound action potential is reduced.

Treatment / Management

There are three main treatment strategies for diaphragmatic palsy if the weakness persists.[7][8][9]

Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation: positive-pressure and bilevel positive-pressure ventilation show success in diaphragmatic weakness. This noninvasive pressure ventilation creates dynamic pressure splint in the airways and prevents paradoxical diaphragmatic movements. It also augments the minute ventilation working in coordination with intercostal muscles. This therapy is started in the night as respiration is compromised in the supine position. In severe cases, intermittent daytime therapy can be used. For more severe cases requiring high-pressure settings and the inability to tolerate oral or nasal masks, a tracheostomy is an option. Advancement in noninvasive technology has enabled noninvasive therapy with tracheostomy interface. If the patient cannot tolerate this setting, then mechanical ventilator can be used. Diaphragmatic paralysis following surgeries is usually temporary and can be treated with this noninvasive, positive-pressure ventilation until the diaphragm or phrenic nerve regains function.

Surgical plication of paralyzed diaphragm: This complicated, invasive procedure, which is done either by open thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracic surgery, has been shown to be effective in relieving symptoms and improving lung function. This prevents the paralyzed diaphragm’s mechanical disadvantage in the thoracic cavity.

Diaphragmatic pacing: This can be used in unilateral phrenic nerve palsy. In this procedure, the phrenic nerve is electrically stimulated to generate mechanical power in the diaphragm. The electric pacer can be placed in the neck or near the diaphragm. The location of generator depends on the cause of the site of phrenic nerve damage.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anterior horn cell or neuromuscular junction disease

- Decreased pulmonary compliance

Pearls and Other Issues

The prognosis of diaphragmatic paralysis depends on its etiology. Temporary weakness after cardiac bypass improves completely; whereas, a progressive neuromuscular disease can lead to respiratory failure. WHen only supportive treatment is provided, many patients show stable lung function or improvement in lung functions within 1 to 2 years.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There are many causes of dysfunction of the diaphragm. Because of the complexity in its management, an interprofessional team that includes an internist, surgeon, intensivist, neurologist, pulmonologist and the nurse practitioner should be involved.

The diaphragm is the primary muscle of respiration, and its weakness can lead to respiratory failure. Various causes can cause diaphragmatic palsy. Depending on severity, the presentation varies from entirely asymptomatic to disabling dyspnea requiring continuous mechanical ventilation. Complete lung function tests, both in sitting and supine positions, should be done in all suspected cases. Historical fluoroscopic examination looking for the movements of the diaphragm is replaced by bedside thoracic ultrasound examination which is equally efficient and without risks of radiation. Treatment depends on the cause. Both surgical and non-surgical methods have shown benefit. Overall prognosis is good except with neuromuscular degeneration conditions. [10][11]